7

Facial Lacerations

Facial soft tissue injuries constitute approximately 3 million visits to emergency departments in the United States each year. Motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) have historically comprised the majority of these injuries. With state and federal seat belt laws, the incidence of MVA-related injuries has recently decreased. However, the overall incidence of facial injuries has remained constant due to sports and job-related injuries, animal bites, and domestic- and interpersonal-violence-related factors.

Assessment

Assessment

The immediate priority for patients with facial injuries is to control the airway and any bleeding. Detailed evaluation of the facial trauma patient is outlined in Chapters 6 and 10.

The physical examination proceeds with inspection and palpation of the patient. Using a systematic approach from the scalp to the base of the clavicles, inspect for lacerations, localized areas of edema, and ecchymoses that may indicate underlying injury. Care must be taken to adequately remove any debris and dried blood in this region, which can easily camouflage lacerations and lead to missed injuries.

Diligently assess cranial nerve function by specific provocative maneuvers. These injuries associated with lacerations are grossly identified by inspection of facial asymmetry at rest and during animation and by assessing sensory function (see Table 6–1 in Chapter 6).

Utilizing palpation, appreciate focal areas of tenderness, depressions, crepitus, and edema that may indicate hematoma or a bony fracture. Patients that have injuries suspicious of facial fractures should have their wounds débrided, closed, and referred for radiographic evaluation (see Chapter 6, Radiographic Evaluation section).

Treatment

Treatment

General Procedures

• Follow basic laceration closure procedures (see Chapter 3)

• Measure the laceration then irrigate, debride, initiate tetanus prophylaxis

• Always be aware of the consequences of your debridement. Debridement in some locations has little consequences; however, débridement around the nose, eyelids, and brow may lead to severe disfigurement.

• When patients present with severe “road rash” or a blast injury, clean the wound meticulously under loupe magnification. This procedure is time consuming, but you will have better results.

• Local anesthesia

Field blocks with 1% lidocaine/1:100,000 epinephrine through a 25- or 27-gauge needle

Field blocks with 1% lidocaine/1:100,000 epinephrine through a 25- or 27-gauge needle

Consider regional blocks for large lacerations isolated to a single nerve distribution

Consider regional blocks for large lacerations isolated to a single nerve distribution

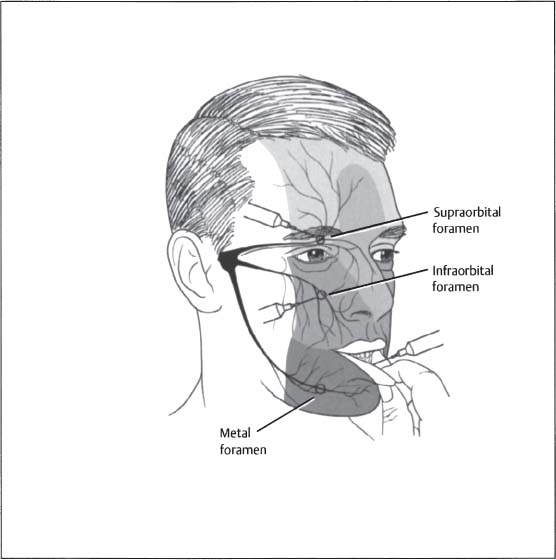

Regional blocks of the trigeminal nerve are performed by instillation of 2 to 4 cc of local anesthesia (1% lidocaine or 0.25% Marcaine (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) just above the periosteum in the region of the nerve (Fig. 7–1).

Regional blocks of the trigeminal nerve are performed by instillation of 2 to 4 cc of local anesthesia (1% lidocaine or 0.25% Marcaine (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) just above the periosteum in the region of the nerve (Fig. 7–1).

Respect anatomical landmarks

Respect anatomical landmarks

• Close lacerations as soon as possible; waiting 2 or 3 days will compromise the results. To avoid depressed scarring, close deep tissue with the following sutures:

Muscle – Monocryl 4–0, Vicryl 4–0 (both by Ethicon, Somerville, NJ)

Muscle – Monocryl 4–0, Vicryl 4–0 (both by Ethicon, Somerville, NJ)

Skin

Skin

Deep layer – Monocryl 5–0,6–0

Deep layer – Monocryl 5–0,6–0

Superficial layer – nylon/Prolene (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) 6–0,7–0

Superficial layer – nylon/Prolene (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) 6–0,7–0

Mucosa – chromic 3–0,4–0

Mucosa – chromic 3–0,4–0

Figure 7–1 Placement procedures for regional blocks of the trigeminal nerve for the repair of facial soft tissue trauma.

• Manage superficial lacerations with minimal disfigurement conservatively

• Cleanse abrasions daily and apply antibiotic ointment (bacitracin ti.d.)

• Close wound

Steri-Strip (3M, St. Paul, MN)

Steri-Strip (3M, St. Paul, MN)

Dermabond (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ)

Dermabond (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ)

For pediatric patients:

• Pursue radiographic evaluation to rule out any associated fractures

• Conscious sedation (Chapter 2) to reduce emotional trauma for the patient and to repair difficult lacerations in specialized areas safely (e.g., periorbital region)

• Use absorbable sutures

Skin

Skin

Deep layer – Monocryl 5–0,6–0

Deep layer – Monocryl 5–0,6–0

Superficial layer – fast-absorbing plain gut 5–0,6–0

Superficial layer – fast-absorbing plain gut 5–0,6–0

Mucosa – chromic 5–0

Mucosa – chromic 5–0

Muscle – 4–0 vicryl

Muscle – 4–0 vicryl

Lip Lacerations

• Approximate each layer of a full-thickness laceration (Fig. 7–2)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree