6 Evaluation of Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse

History, Physical Examination, and Office Tests

Urinary incontinence can be a symptom of which patients complain, a sign demonstrated on examination, or a condition (i.e., diagnosis) that can be confirmed by definitive studies. When a woman complains of urinary incontinence, appropriate evaluation includes exploring the nature of her symptoms and looking for physical findings. The history and physical examination are the first and most important steps in the evaluation. A preliminary diagnosis can be made with simple office and laboratory tests, with initial therapy based on these findings. If complex conditions are present, if the patient does not improve after initial therapy, or if surgery is being considered, definitive, specialized studies are usually necessary.

Many of the accepted definitions of pelvic organ prolapse are based on expert opinions and consensus rather than epidemiologic or clinical data. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology defines pelvic organ prolapse as the protrusion of pelvic organs into the vaginal canal (1995, bull no. 214). More specifically, in a terminology workshop convened by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for researchers in female pelvic floor disorders, pelvic organ prolapse is defined as the descent of vaginal segments to within 1 cm of the hymen or lower (Weber et al., 2001). Terminologies such as cystocele and rectocele were intentionally not used by Weber et al. because they implied an unrealistic certainty as to the specific organs behind the vaginal wall at the time of physical examination.

Importantly, although most clinicians can recognize the extremes of normal support versus severe prolapse, most cannot objectively state at what point vaginal laxity becomes pathologic and requires intervention. Limited data are available concerning the normal distribution of pelvic organ prolapse in the population and the correlations between symptoms and physical findings. In a study of 497 women, Swift (2000) demonstrated that the distribution of prolapse in a population exhibited a bell curve, with the majority of women having stage I or II prolapse by the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) classification system (see Chapter 5) and only 3% having stage III prolapse. This signifies that, at baseline, a majority of women, especially those who have borne children, have some degree of pelvic relaxation. However, these women are generally asymptomatic and will develop symptoms only as their prolapse increases in severity (Swift et al., 2005). Therefore, even if prolapse is found on physical examination by the earlier definition, it may not be clinically relevant and may not require intervention if the patient is asymptomatic.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

History of Urinary Incontinence

Box 6-1 lists questions that are helpful in evaluating incontinence in women. The first question is designed to elicit the symptom of stress incontinence (i.e., urine loss with events that increase intra-abdominal pressure). The symptom of stress incontinence is usually (but not always) associated with the diagnosis of urodynamic stress incontinence. Questions 2 through 8 help elicit the symptoms associated with detrusor overactivity. The symptom of urge incontinence is present if the patient answers question 3 affirmatively. Frequency (questions 4 and 5), bed-wetting (question 6), leaking with intercourse (question 8), and a sense of urgency (questions 2 and 7) are all associated with detrusor overactivity. Questions 9 and 10 help define the severity of the problem. Questions 11 through 13 screen for urinary tract infection and neoplasia, and questions 14 through 16 are designed to elicit symptoms of voiding dysfunction.

BOX 6-1 HELPFUL QUESTIONS IN THE EVALUATION OF FEMALE URINARY INCONTINENCE

A complete list of the patient’s medications (including nonprescription medications) should be sought to determine whether individual drugs might influence the function of the bladder or urethra, leading to urinary incontinence or voiding difficulties. A list of drugs that commonly affect lower urinary tract function is shown in Table 6-1. In these cases, altering drug dosage or changing to a drug with similar therapeutic effectiveness, but with fewer lower urinary tract side effects, will often improve or cure the offending urinary tract symptom.

Table 6-1 Medications That Can Affect Lower Urinary Tract Function

| Type of Medication | Lower Urinary Tract Effects |

|---|---|

| Diuretics | Polyuria, frequency, urgency |

| Caffeine | Frequency, urgency |

| Alcohol | Sedation, impaired mobility, diuresis |

| Narcotic analgesics | Urinary retention, fecal impaction, sedation, delirium |

| Anticholinergic agents | Urinary retention, voiding difficulty |

| Antihistamines | Anticholinergic actions, sedation |

| Psychotropic agents | |

| Antidepressants | Anticholinergic actions, sedation |

| Antipsychotics | Anticholinergic actions, sedation |

| Sedatives/hypnotics | Sedation, muscle relaxation, confusion |

| α-Adrenergic blockers | Stress incontinence |

| α-Adrenergic agonists | Urinary retention, voiding difficulty |

| Calcium-channel blockers | Urinary retention, voiding difficulty |

Urinary Diary

Urinary diaries are a useful and accepted research method to measure the severity of incontinence and as an outcome measure after interventions. This is reviewed in detail in Chapter 39.

History of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

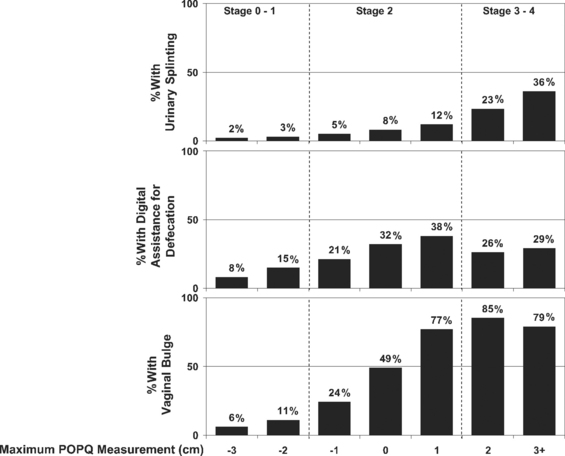

Vaginal prolapse in any compartment—anterior, apical, or posterior—can manifest as vaginal fullness, pain, and/or protruding mass. In a recent study by Tan et al. (2005), the feeling of “a bulge or that something is falling outside the vagina” had a positive predictive value of 81% for pelvic organ prolapse, and the lack of this symptom had a negative predictive value of 76% for predicting prolapse at or past the hymen. Not surprisingly, increased degree of prolapse, especially beyond the hymen, is associated with increased pelvic discomfort and visualization of a protrusion. The association of POPQ measures on examination with three commonly related symptoms—urinary splinting, digital assistance with defecation, and vaginal bulge—is shown in Figure 6-1.

Stress urinary incontinence and voiding difficulties can occur in association with anterior and apical vaginal prolapse. However, women with advanced degrees of prolapse may not have overt symptoms of stress incontinence because the prolapse may cause a mechanical obstruction of the urethra, thereby preventing urinary leakage. Instead, these women may require vaginal pressure or manual replacement of the prolapse to accomplish voiding. Therefore, they are at risk for incomplete bladder emptying, and recurrent or persistent urinary tract infections, and for the development of de novo stress incontinence after the prolapse is repaired. Patients who require digital assistance to void, in general, have more advanced degrees of prolapse. In addition to difficulty voiding, other urinary symptoms, such as urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence, are found in women with prolapse. However, it is not clear whether the severity of prolapse is directly associated with more irritative voiding symptoms or bladder pain.

Although the relationship between sexual function and pelvic organ prolapse is not clearly defined, questions regarding sexual dysfunction must be included in the evaluation of any patients with prolapse. Patients may report symptoms of dyspareunia, decreased libido and orgasm, and increased embarrassment with altered anatomy that affects body image. Some studies have reported that prolapse adversely affected sexual functioning, with subsequent improvement in sexual function after repair of prolapse (Barber et al., 2002; Rogers et al., 2001; Weber et al., 2000). However, Burrows et al. (2004) showed little correlation between the extent of prolapse and sexual dysfunction. Evaluating sexual function may be especially difficult in this patient population because the hindrances to sexual function may include factors other than prolapse, such as partner limitations and functional deficits.

Symptoms of incontinence and prolapse and their impact on the woman can be measured or quantified using a number of easy-to-use and validated questionnaires measuring symptom severity, quality of life, and sexual function. These outcome measures can be useful in clinical practice and in research; they are reviewed in detail in Chapter 39.

Gynecologic Examination

After the resting vaginal examination, the patient is instructed to perform Valsalva maneuver or to cough vigorously. During this maneuver, the order of descent of the pelvic organs is noted, as is the relationship of the pelvic organs at the peak of increased intra-abdominal pressure. The presence and severity of anterior vaginal relaxation, including cystocele and proximal urethral detachment and mobility, or anterior vaginal scarring, are estimated. Associated pelvic support abnormalities, such as rectocele, enterocele, and uterovaginal prolapse, are noted. The amount or severity of prolapse in each vaginal segment should be measured, staged, and recorded according to POPQ guidelines noted in Chapter 5. A rectovaginal examination is required to fully evaluate prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall and perineal body. Digital assessment of bowel contents in the rectovaginal septum during straining examination can help to diagnose an enterocele. Other clinical observations and tests that help delineate prolapse include (1) cotton swab testing for the measurement of urethral axis mobility (Q-tip test); (2) measurement of perineal descent; (3) measurement of the transverse diameter of the genital hiatus or of the protruding prolapse; (4) measurement of vaginal volume; (5) description and measurement of posterior prolapse; and (6) examination techniques differentiating between various types of defects (e.g., central versus paravaginal defects of the anterior vaginal wall). Inspection should also be made of the anal sphincter because fecal incontinence is often associated with posterior vaginal support defects. Grossly, women with a torn external sphincter may have scarring or a “dovetail” sign on the perineal body.

Anterior vaginal wall descent usually represents bladder descent with or without concomitant urethral hypermobility. However, in 1.6% of women with anterior vaginal prolapse, an anterior enterocele can mimic a cystocele on physical examination. Furthermore, lateral paravaginal defects, identified as detachment of the lateral vaginal sulci, may be distinguished from central defects, seen as a midline protrusion with preservation of the lateral sulci, by using a curved forceps placed in the anterolateral vaginal sulci directed toward the ischial spine. Bulging of the anterior vaginal wall in the midline between the forceps blades implies a midline defect; blunting or descent of the vaginal fornices on either side with straining suggest lateral paravaginal defects. However, researchers have shown that the physical examination technique to detect paravaginal defects is not particularly reliable or accurate. In a study by Barber et al. (1999), of 117 women with prolapse, the sensitivity of clinical examination to detect paravaginal defects (92%) was good, yet the specificity (52%) was poor. Despite a high prevalence of paravaginal defects, the positive predictive value was only 61%. Less than two thirds of women believed to have a paravaginal defect on physical examination were confirmed to possess the same at surgery. Another study by Whiteside et al. (2004) demonstrated poor reproducibility of clinical examination to detect anterior vaginal wall defects. Thus, the clinical value of determining the location of midline, apical, and lateral paravaginal defects remains unknown.

In regard to posterior prolapse, clinical examinations do not always accurately differentiate between rectoceles and enteroceles. Some investigators thus have advocated performing imaging studies to further delineate the exact nature of the posterior wall prolapse. Traditionally, most clinicians believe that they are able to detect the presence or absence of these defects without anatomically localizing them. However, little is known regarding the accuracy or use of clinical examinations in evaluating the anatomic locations of prolapsed small or large bowel or of specific defects in the rectovaginal space. Burrows et al. (2003) found that clinical examinations often did not accurately predict the specific location of defects in the rectovaginal septum that were subsequently found intraoperatively. Clinical findings corresponded with intraoperative observations in 59% of patients and differed in 41%; sensitivities and positive predicative values of clinical examinations were less than 40% for all posterior defects. However, the clinical consequence of not detecting preoperative defects remains unclear.