Evaluating Implant Integrity and Explantation Options and Techniques

Over the past decade, many plastic surgeons have seen a number of patients with concerns about or problems with a previously placed breast implant. In the early 1990s many of these consultations were prompted by the adverse publicity1 surrounding breast implants, such as concerns about safety issues,2 especially with regard to any link between the presence of silicone gel breast implants and the development of connective tissue disease or other diseases. These patients were extremely anxious and even angry about presumed health problems with their breast implants. Two extensive reviews of virtually all the data on silicone gel implants published in the medical literature3,4 and many other peer-reviewed studies5, 6, 7 and 8 have now disproved the potential induction of or link between any known disease process and silicone implants, thus making it possible now to reassure patients who have had implants placed for any reason about the safety of these devices.9

Nevertheless, it is imperative that the plastic surgeon employ a thorough and systematic evaluation of all patients who have undergone previous breast implantation if there is a suspected problem with the implant(s). This analysis is directed at establishing the status of implant integrity and entails a careful evaluation of the patient’s breasts from an aesthetic and general breast health perspective.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

In my practice the approach to the potential explantation patient entails taking a careful history, noting the chief complaint and other complaints, and a detailed review of past breast health history (including all mammograms, biopsies, and operations) and other medical conditions, followed by performing a careful physical examination. Appropriate laboratory and breast imaging studies are then recommended and additional consultations sought if indicated. The goal is to make a diagnosis regarding any implant problem.

The history is very important. It must include details of the previous operation(s), the type of implant, anatomic position of the implant, complications of the previous

procedure and any related incidental occurrences such as trauma to the breast, particularly searching for a history of closed capsulotomies, etc. A review of previous operative reports and physician records is the most precise way of gaining the most accurate knowledge about the previous surgery(ies). Specific complaints or problems related to the breasts most often include firmness as the result of capsular contracture, asymmetry, nipple or skin sensory changes, breast pain, and changes in implant position or the development of a mass in the breast or an irregularity that may be related to the implant edge. The physician must key into symptoms of pain, especially the occurrence of burning pain that may involve the breast, lateral chest area, or axillary region. This symptom can result from implant rupture. Previous breast problems are also important to note. Such problems include any history of previous breast masses, imaging studies, and all breast biopsies and pathology reports pertaining to them. Changes in the patient’s breast examination (noted by either the patient or the physician) and the new onset of pain symptoms in the breasts are important to catalogue. Obviously any family history of breast cancer is also important to note.

procedure and any related incidental occurrences such as trauma to the breast, particularly searching for a history of closed capsulotomies, etc. A review of previous operative reports and physician records is the most precise way of gaining the most accurate knowledge about the previous surgery(ies). Specific complaints or problems related to the breasts most often include firmness as the result of capsular contracture, asymmetry, nipple or skin sensory changes, breast pain, and changes in implant position or the development of a mass in the breast or an irregularity that may be related to the implant edge. The physician must key into symptoms of pain, especially the occurrence of burning pain that may involve the breast, lateral chest area, or axillary region. This symptom can result from implant rupture. Previous breast problems are also important to note. Such problems include any history of previous breast masses, imaging studies, and all breast biopsies and pathology reports pertaining to them. Changes in the patient’s breast examination (noted by either the patient or the physician) and the new onset of pain symptoms in the breasts are important to catalogue. Obviously any family history of breast cancer is also important to note.

The presence of generalized systemic symptoms must also be noted. These include any history of myalgias, arthralgia, fatigue, hair loss, and dryness of mucous membranes, as well as any neurologic complaints. It is important to thoroughly review previous diseases, including the presence of known connective tissue disease, cardiac disease, respiratory disease, thyroid problems, and other endocrine diseases, during the initial evaluation.

In my practice most often the typical patient has experienced no specific breast complaints but is referred for evaluation after breast imaging studies have suggested the diagnosis of implant rupture.10, 11, 12, 13 and 14 Importantly, although patients experiencing local discomfort in the breast related to capsular contracture or implant rupture might be improved by implant removal, it has been my experience that patients who are experiencing any systemic complaint(s) are rarely improved by the removal of the implants. Patients are informed of this before any planned explantation procedure.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

As with all plastic surgery evaluations, the first part of the examination entails careful inspection. For the patient with a possible implant problem, this begins with observing the movement and posture of the patient, as well as her general appearance. Vital signs are recorded, along with height, weight, and bra size. Next, the appearance of the breasts is analyzed for any asymmetry in volume, skin envelope dimension or quality, nipple areola size or location, and degree of mammary ptosis. It is important to assess whether the implant is frankly visible or causing distortion of the breast (Fig. 4-1), implying an advanced capsular contracture or perhaps rupture. Perhaps most important is noting the location of previous scars and taking into account their potential effect on the blood supply of the nipple areolar complex (NAC). Any asymmetry, distortion of the breast tissue, and nipple irregularities are also noted.

Next, the relationship of the NAC to the breast mound and implant is noted. It is also important to note the relative degree of ptosis and to determine the relationship of the existing breast tissue to the underlying implant. It is relatively common for the breast tissue to settle away from the implant (see Fig. 4-1), especially in patients approaching the fifth decade, or in situations in which the implants have been in place for more than 15 years. Very often the breast will exhibit a dependent appearance, especially if the implants are of the smooth-walled saline variety. In these cases some form of a mastopexy may need to be incorporated as part of the surgical plan.

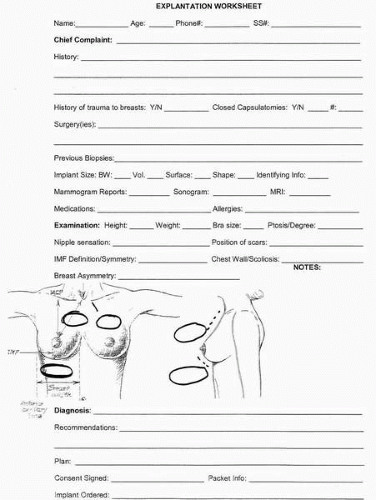

A worksheet with a breast diagram (Fig. 4-2) is completed detailing the anatomic and tissue features of the breast, including the base width and the relationship of the NAC to the inframammary (IM) fold and the suprasternal notch (SSN), with notations about the breast skin and parenchyma. The location of all previous breast scars is also recorded on the diagram. In addition, information about the patient’s past breast history, including details of the previous surgery(ies), is entered. As mentioned in Chapter 3, this includes the type, size, and position of the indwelling implant and notations regarding incisional approaches along with any information about previous mastopexies. Sensation of the breast skin and nipple areola area is also noted.

Following this the breast is palpated for any abnormalities in the parenchymal tissue or on the surface of the implant itself. The patient is asked to contract her pectoralis major muscles (PMMs) and in this way whether the implant is located in the subglandular or submuscular position is suggested (if such information cannot be obtained from the previous records). This maneuver gives the surgeon an insight into the degree of distortion of the breast with contraction of the PMM. The examiner then notes the degree of firmness in the implant. The firmness is graded on a spectrum of none to severe and is recorded in the form of the widely accepted Baker Classification Score15 (Table 4-1). The edge of the implant is then carefully palpated for, specifically to assess for any evidence of irregularity, rippling or undulations, firmness, or discrete masses that might be adjacent to the implant. Next, the surgeon observes for the presence of any nipple discharge or nipple irregularity. The skin is carefully observed for any distortion or mass. The axillary area is carefully evaluated for any sign of palpable abnormality, including lymph nodes, masses, and previous scars.

IMAGING MODALITIES FOR BREAST IMPLANTS

I believe that the diagnostic impression of whether the implant is ruptured or intact is almost never obtained from physical examination alone. The exception to this is the case of an easily palpable abnormality in the breast tissue (especially if it is an acute change) related to an episode of direct trauma to the breast. More often the diagnosis of implant integrity can only be obtained from an interpretation of imaging studies of the breast, which include a combination of mammography,10 breast sonography,11,12 and magnetic resonance (MR) scanning.13,14

TABLE 4-1 Baker Classification of Capsular Contracture | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

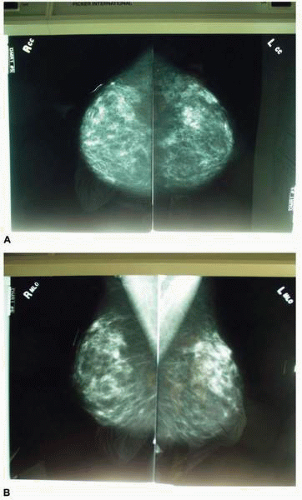

The mammogram remains the standard way to image the breast tissue in every woman’s breast,10 regardless of whether an implant is present.16 It is the only method by which microcalcifications in the breast can be visualized. It employs x-rays of the breast in various planes, including the craniocaudad and mediolateral views (Fig. 4-3A,B). I instruct patients to follow the mammography schedule as proscribed by the American Cancer Society.16 I instruct the patient to have the first mammogram performed at age 35, the next at age 40, mammograms every other year until age 50, and yearly studies thereafter.16

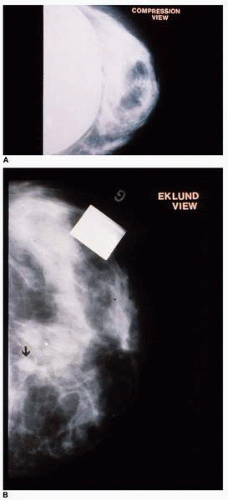

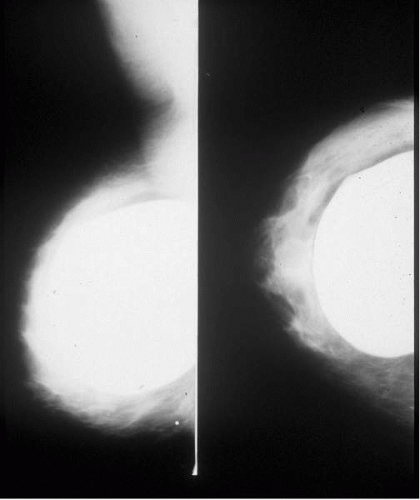

The presence of a breast implant limits the amount of breast tissue that can be imaged to a variable extent due to the radio-opacity of the implant itself.10 The amount of breast tissue that is concealed varies from approximately 9% to 49%17 depending on the position of the implant and whether capsular contracture exists.18 To increase the amount of tissue that can be imaged, special displacement views, as described by Eklund10 (Fig. 4-4A,B), are widely used. With this technique the implant is pushed posteriorly toward the chest wall and the breast tissue is distracted anteriorly to obtain increased visualization of the breast parenchymal tissue. This must be done gently in a radiology unit experienced in performing mammography in patients with implants because implant rupture is a rare reported complication of mammography.19

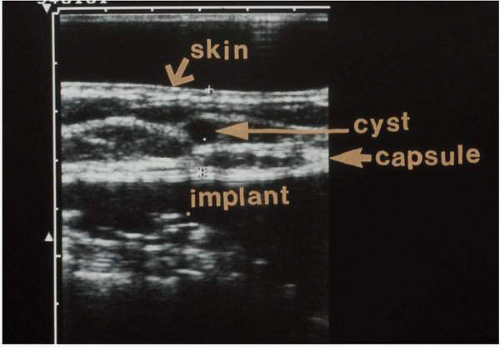

The breast tissue that is most concealed is that area alongside the implant itself11 (Fig. 4-5). To obtain the best visualization of this area, ultrasound or breast sonography has been widely employed. It provides a valuable adjunct to the mammographic imaging studies. Sonography relies on transmitted sound waves, which are directed through the breast and reflected back to a receiving probe. It has long been used to aid in the diagnosis of breast pathology because it can provide information as to whether a palpable or mammographically demonstrated lesion is cystic or solid (Fig. 4-6).

In a similar way sonography is helpful in imaging a breast implant because there is differential sound wave transmission through the breast tissue and breast implant. Therefore, the sonography examination of the breast produces an image of the implant that is separate and distinct from the surrounding breast tissue. The implant appears as a nearly anechoic structure that is dark on the sonographic image. In contrast, the breast tissue is hyperechoic (or appears white). This yields a picture of the implant as sharply distinct and contrasted from the surrounding breast tissue11,12 (Fig. 4-7).

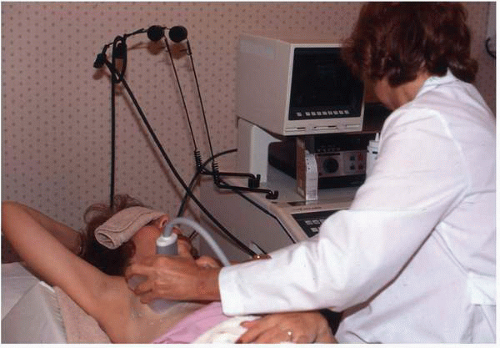

Sonography of the breast is highly operator dependent.11,12 It yields the most useful information when performed by a radiologist who has taken a history, personally examined the patient, and evaluated the mammograms. This allows a careful, focused examination of a specific area of the breast that may require that the patient be placed in various positions (Fig. 4-8).

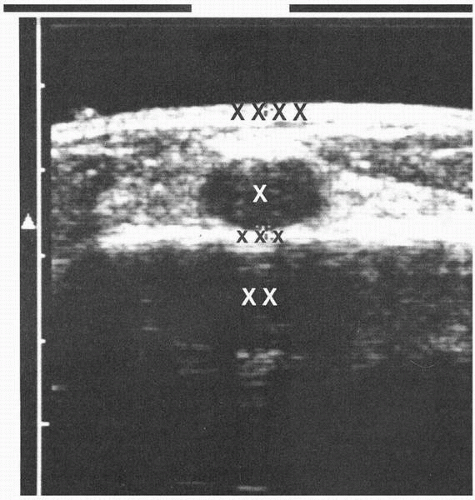

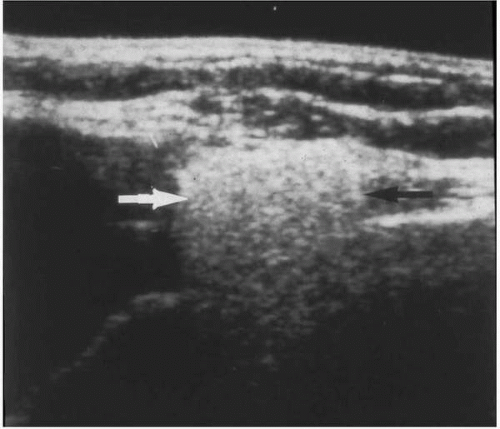

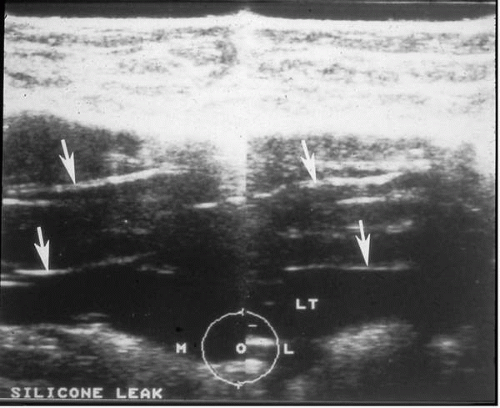

As previously noted, because of the differential sound wave transmission characteristics of breast tissue and silicone, in the hands of an experienced operator the technique of sonography is highly reliable for making the diagnosis of extracapsular implant rupture. In this situation, silicone gel has moved beyond the confines of the periprosthetic fibrous capsule into the breast tissue and usually lies adjacent to the implant. The ultrasound appearance of such a condition is that characteristic of a snowstorm12 (Fig. 4-9). It is different from the sharply marginated interface between the implant and the surrounding breast tissue. Our experience reflects that such a finding is highly predictive (>98%) of extracapsular rupture that has been confirmed at surgery.11,12,20 We believe that the presence of this snowstorm appearance allows the physician to make the diagnosis of extracapsular breast rupture with confidence, and therefore it allows him or her to recommend implant removal to the patient.

FIGURE 4-3. Standard mammographic views for screening mammogram. A, Craniocaudal view. B, Mediolateral view. |

Intracapsular rupture is more difficult to image with sonography of the implant. With intracapsular rupture a tear has occurred in the elastomer shell of the silicone gel

implant, but there has been no egress of the silicone gel outside the periprosthetic capsule surrounding the implant. Because the gel is confined within the periprosthetic capsule (the rupture is contained within the collagen envelope surrounding the implant), it is called an intracapsular rupture. The prevalence and incidence of this condition is difficult to establish with certainty because most often these patients do not have any symptoms and there are no changes in the appearance or feel of the breast. With intracapsular rupture the sonogram may show an abnormal reflectance of sound waves, referred to as a stepladder sign12 (Fig. 4-10), which is the result of

sound reflecting off the surfaces of the elastomer shell that lies within the aggregate of the gel.

implant, but there has been no egress of the silicone gel outside the periprosthetic capsule surrounding the implant. Because the gel is confined within the periprosthetic capsule (the rupture is contained within the collagen envelope surrounding the implant), it is called an intracapsular rupture. The prevalence and incidence of this condition is difficult to establish with certainty because most often these patients do not have any symptoms and there are no changes in the appearance or feel of the breast. With intracapsular rupture the sonogram may show an abnormal reflectance of sound waves, referred to as a stepladder sign12 (Fig. 4-10), which is the result of

sound reflecting off the surfaces of the elastomer shell that lies within the aggregate of the gel.

FIGURE 4-4. A-B, Eklund displacement views illustrating the increased visualization of the breast tissue (A) over the standard compression view as the implant is displaced posteriorly. |

FIGURE 4-5. Breast tissue, which is most obscured by the implant, is alongside and posterior to the implant as seen on these x-ray films. |

FIGURE 4-6. Ultrasound of the breast in patient with a cystic lesion anterior to the breast implant. This method delineates the implant and identifies the breast mass as cystic. |

A more sensitive, specific, and accurate way to image a breast implant, especially with regard to the diagnosis of intracapsular rupture, is by using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).13,14 This modality allows more precise delineation of the elastomer shell, periprosthetic capsule, and gel within the implant. In situations where there is a frank tear of the elastomer membrane, the shell appears to become intermingled within the central portion of the gel and appears as a serpentine group of lines, which has been named the linguini sign13 (Fig. 4-11). It is highly suggestive of intracapsular rupture. I use MRI as my second modality for establishing the diagnosis of intracapsular rupture and will order this study if the sonographic evaluation of the implant is equivocal or nonconclusive. Our data20 indicate that the sensitivity and specificity of MRI exceed 90% in the diagnosis of intracapsular rupture, and this is consistent with other findings recorded in the literature.

FIGURE 4-9. Characteristic “snowstorm” appearance of an extracapsular rupture as imaged by breast sonogram. |

FIGURE 4-10. The characteristic stepladder sign of intracapsular rupture of a silicone gel implant seen with breast sonography. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree