4 Epidemiology and Psychosocial Impact of Pelvic Floor Disorders

Because the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders increases with age, the changing demographics of the U.S. population will result in even more affected women. Based on projections from the Census Bureau, the number of women age 60 and over will almost double between 2000 and 2030. For example, the number of women ages 60 to 69 will increase from 10 to 20 million. Even absolute population numbers do not fully reflect the real and growing burden of pelvic floor disorders on women as they age. Luber et al. (2001) estimated that the demand for health care services related to pelvic floor disorders will increase at twice the rate of the population.

PREVALENCE, INCIDENCE, AND REMISSION

Urinary Incontinence

Severity of incontinence can be characterized by the frequency of incontinent episodes, quantity of urine lost, or both. When the severity of urine loss is defined as “daily,” “weekly,” or “most of the time,” the reported prevalence ranges from 3% to 17% for women in the community. This estimate corresponds more closely to the clinical estimate of disease because it probably identifies women at the more severe end of the spectrum who present for clinical care. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in nursing homes is much higher than in women in the community, with most studies reporting prevalence greater than 50%, especially in facilities where residents have more severe functional impairments.

Much less information is available on incidence, progression, or remission, compared with prevalence, for urinary incontinence (and even less for all other pelvic floor disorders). Young and middle-aged women develop urinary incontinence at a lower rate, 3% to 8% per year, than older women. Herzog et al. (1990) reported a 20% incidence of incontinence per year in women age 60 and over. However, Grodstein et al. (2004) reported a much lower incidence per year of 3.2% occasional and 1.6% frequent incontinence in women ages 50 to 75. As noted earlier, this emphasizes the difficulty of directly comparing findings across the literature due to the use of different definitions of disease.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

In studies of women who were not seeking care for prolapse, mild to moderate prolapse (at or above the hymen, stages I–II prolapse by ICS standards) has been found in up to 48% of women. More advanced prolapse (beyond the hymen, stage III or IV) occurs in about 2% of women. In 412 women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative, Handa et al. (2004) reported an annual average incidence of 9.3 cases of anterior vaginal prolapse, 5.7 cases of posterior vaginal prolapse, and 1.5 cases of uterine prolapse per 100 women per year. In women with at least grade 1 prolapse at baseline, progression occurred in 10.7 cases of anterior vaginal prolapse, 14.8 of posterior, and 2.0 of uterine prolapse per 100 women per year. Interestingly, regression occurred more commonly than incidence or progression, especially from grade 1 to grade 0. Anterior vaginal prolapse regressed from grade 1 to 0 in 23.5 cases per 100 women per year, and from grades 2 to 3 to 0 in 9.3 cases per 100 women per year. Posterior vaginal prolapse regressed in 25.3 cases, as did uterine prolapse in 48 cases per 100 women per year. This serves to emphasize that prolapse is a dynamic condition, and factors related to progression and remission need further study.

RISK FACTORS FOR PELVIC FLOOR DISORDERS

Sex

Urinary incontinence is two to three times more common in women than in men. The gender difference is most pronounced among adults under age 60 because of the very low prevalence of urinary incontinence in younger men. These sex differences are consistent, whether the measure is any incontinence, severe incontinence, or irritative bladder symptoms. The symptom of stress incontinence is uncommon in men who have not had surgery, but voiding problems are more common, especially in elderly men, in part due to prostate conditions.

Age

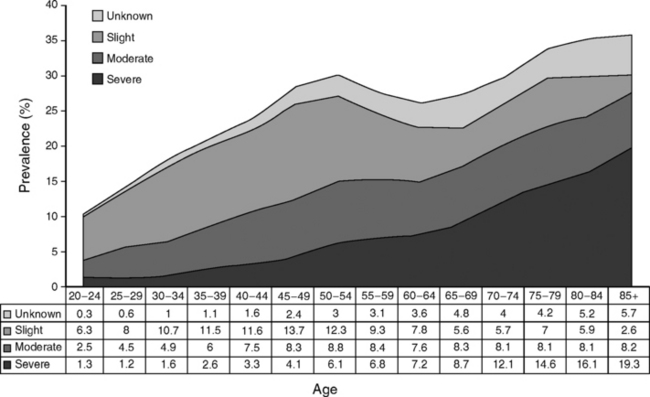

The prevalence of urinary incontinence increases with age, although it is not a linear relationship. Recent studies show a broad peak in prevalence from ages 40 to 60, with a steady increase occurring after ages 65 to 70 (Fig. 4-1). The type of incontinence may differ by age, with many studies suggesting a higher prevalence of stress incontinence in younger women, compared with more urge incontinence in older women; however, not all studies confirm this, and the prevalence of mixed (stress and urge) incontinence varies widely in different studies.

Figure 4-1 Prevalence of urinary incontinence by age group and severity.

(From Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Sandvik H, Hunskaar S. A community-based epidemiological survey of female urinary incontinence: the Norwegian EPINCONT Study. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:1150, with permission.)

Urinary symptoms are found in over half of institutionalized elderly women. In addition to lower urinary tract dysfunction contributing to incontinence, nonurologic causes of incontinence, such as cognitive impairment, immobility, medications, and metabolic causes of excess urine output (e.g., diabetes) are often present. Jirovec and Wells (1990) observed that when multiple variables were examined together, mobility emerged as the best predictor of urinary control, followed by cognitive impairment. Therapy should always include a combination of urologic treatments with nonurologic treatments in dealing with urinary incontinence in the elderly, particularly in nursing home residents.

Most studies of fecal incontinence show increased prevalence with age. In a study of over 10,000 men and women in the United Kingdom, Perry et al. (2002) reported fecal incontinence in 0.9% of adults ages 40 to 64 and in 2.3% age 65 and over. Also from the United Kingdom, Crome et al. (2001) reported that the rate of fecal incontinence roughly doubled by decade of age, from 4.7% in women ages 70 to 79, to 10.1% in women ages 80 to 89, to 20.3% in women ages 90 to 99. As with urinary function, the effect of age on anorectal function is multifactorial, and the presence of comorbid conditions contributes to worsening symptoms. Incontinence, both urinary and fecal, is strongly associated with cognitive impairment and physical limitations.

Although available data are limited, virtually all studies show that the prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse increases steadily with age. This has been shown in case-control studies, prospective studies, and studies of surgery for prolapse. In the Women’s Health Initiative, at baseline, uterine prolapse was observed in 14.2% of 16,616 women. Anterior vaginal prolapse was observed in about one-third of the study population, regardless of hysterectomy status (32.9% with and 34.3% without hysterectomy); posterior vaginal prolapse was present in about one-fifth, similarly unrelated to hysterectomy (18.3% and 18.6%, respectively). For uterine prolapse, regression analyses showed a 16% to 20% increase in the odds ratio (OR) for having prolapse by decade of life. Studies of surgery for prolapse, which are likely to reflect the more severe end of the clinical spectrum of prolapse, consistently show increased rates of surgery by age (until age 80 and above). Olsen et al. (1997) reported prolapse surgery rates (per 1000 women per year) of 1.24 for women ages 50 to 59, 2.28 for those ages 60 to 69, and 3.43 for those ages 70 to 79.

Race

No reports related to race or ethnicity are available for fecal incontinence.

In many studies of prolapse, the populations are predominantly white, thereby limiting analyses related to race and ethnicity. In studies that do have significant minority representation, differences seem to appear in the occurrence of prolapse by race. In the Women’s Health Initiative, black women had a lower risk of prolapse (odds ratio of 0.65 or less), compared with white women. Hispanic women had a higher risk of uterine and anterior vaginal prolapse, with odds ratios of 1.24 and 1.20, respectively; the risk of posterior vaginal prolapse was not significantly different compared with white women. In a case-control study of 447 women, Swift et al. (2001) reported a statistically significant lower risk for prolapse in women of nonwhite race (although the magnitude of the lowered risk was not reported). Racial differences in the bony pelvis may play a role in determining a woman’s risk of prolapse, possibly by influencing the likelihood or extent of injury to pelvic support at childbirth.

Childbirth

Early after delivery, the type of delivery has the strongest effect. In one of the few randomized trials of delivery type to address this (although not as a primary aim), the Term Breech Trial (Hannah et al., 2002) found less urinary incontinence in the planned cesarean delivery group (4.5%, relative risk 0.62) compared with the planned vaginal delivery group (7.3%) at 3 months postpartum. Because 43% of women in the planned vaginal delivery group actually had cesarean delivery, the results of this study probably underestimate the magnitude of the early difference between cesarean and vaginal delivery.

In a large community-based observational study in Norway of women less than age 65 (the Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trondelag [EPINCONT] study), the prevalence of any incontinence was 10.1% in nulliparous women, compared with 15.9% in women delivered by cesarean, and 21.0% in women who delivered vaginally. The effect of delivery type diminished with age, such that the prevalence of incontinence was similar regardless of the type of delivery in the oldest age group of women studied (ages 50 to 64). Viktrup (2002) showed that incontinence 5 years after the first delivery was not influenced by the type of delivery. A study by Wilson et al. (1996) showed that the risk of incontinence accumulated with the number of cesarean deliveries; after three or more cesarean deliveries, the prevalence of incontinence was similar (38.9%), compared with women who delivered vaginally (37.7%).

Most studies show midline episiotomy as one of the strongest risk factors for anal sphincter damage and, therefore, fecal incontinence. Especially because current methods of surgical repair leave persistent anal sphincter defects in up to 85% of women and are associated with high rates of postpartum symptoms, it is critically important to prevent the initial damage at vaginal delivery. Even cesarean delivery does not protect women completely from the possibility of postpartum anorectal dysfunction. Recent studies have identified new fecal incontinence symptoms even after elective cesarean delivery without labor. At this point, it is unknown whether this reflects changes due to pregnancy, the surgical delivery, or possibly both.

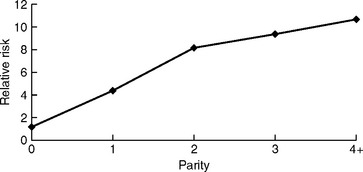

Most (but not all) studies show that parity is linked to the prevalence of prolapse, although the magnitude of the effect varies in different studies. Mant et al. (1997) reported a strong cumulative effect of parity on the risk of inpatient admission for prolapse. The effect was greatest for the first and second births and less so for three or more births (Fig. 4-2). In cross-sectional data from the Women’s Health Initiative, Hendrix et al. (2002) found that the first birth approximately doubled the risk of uterine prolapse and anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse; each additional birth increased the risk by 10% to 21%. In longitudinal data from a subset of women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative, Handa et al. (2003) showed that the incidence of anterior vaginal prolapse increased by 31% for each additional pregnancy; similar associations were seen for uterine and posterior vaginal prolapse, although specific data were not reported.