22 Obliterative Procedures for Vaginal Prolapse

As women live longer and healthier lives, pelvic floor disorders are becoming even more prevalent and an increasingly important health and social issue. An estimated 63 million women will be 45 years old or greater by 2030, and 33% of the population will be postmenopausal by 2050. Over 10% of women will undergo surgery for pelvic organ prolapse or incontinence in their lifetime; the reoperation rate for failure is approximately 30%. Due to an increasing number of women entering the eighth and ninth decades of life, many of these individuals will present with pelvic organ prolapse, often after unsuccessful trials of conservative treatment or surgeries. These women frequently have concomitant medical issues and are not sexually active, making extensive surgery not suitable. This chapter discusses the use of obliterative procedures as a surgical option for pelvic organ prolapse in this patient population.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

Before the introduction of operative procedures, uterine prolapse had been treated unsuccessfully with various techniques, including vaginal packing and instillation with caustic substances. Early forms of surgical treatment were later promoted in the form of introital narrowing and/or excision of the prolapsing areas. Gerardin of Metz, in 1823, first described the reapproximation of denuded vaginal mucosa as an obliterative procedure. As noted by Tauber (1947), the procedure was first performed by Neugebauer of Warsaw, in 1867, by suturing the anterior and posterior vaginal walls together after removing a 6 × 3 cm rectangular area of vaginal mucosa in each segment. Leon Le Fort of Paris popularized the procedure in 1877 and modified the previous description by Neugebauer by creating a narrower and longer area of mucosal removal and the addition of a posterior colpoperineoplasty at 8 postoperative days (Taft, 1889). In 1881, Berlin reported the first three American cases performed at the New England Hospital for Women.

In the early twentieth century, reports in the literature were mainly technical descriptions with brief mention of outcome data. Baer and Reis, in 1928, reported a 100% success rate in a group of 14 women who received Le Fort colpocleisis. Phaneuf, in 1935, had two vault recurrences and one anterior vaginal prolapse in a total of 20 patients. In 1936, Adair and DaSef published their series of 38 patients, one of whom developed a recurrence of uterine prolapse through a lateral channel, and two had recurrence of cystoceles. Collins and Lock (1941) had a 94% success rate in 31 patients, whereas Mazer and Israel (1948) reported a 97% success rate in 38 women.

Martin (1898) from Europe has been credited for the initial use of hysterectomy and complete vaginectomy for the correction of uterovaginal prolapse. Total colpocleisis with levator plication was first reported in 1901 in the English literature by Edebohls. He described four cases of panhysterocolpectomy, which involved vaginal hysterectomy, vaginectomy, and visceral reduction via purse-string sutures.

The incorporation of levator plication into the procedure was described by Phaneuf, in 1935, in five subjects. Masson and Knepper, in 1938, published a case series of 23 patients who underwent vaginectomy, with or without hysterectomy, purse-string reduction of the viscera, levator plication, and perineorrhaphy. No recurrences were observed in a series of 60 cases of vaginal hysterectomy with vaginectomy and levatorplasty by Williams in 1950.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

The evaluation and staging of pelvic organ prolapse are described in Chapters 5 and 6. Most gynecologists would agree that optimal treatment is contingent upon obtaining a thorough history and physical examination findings as well as an understanding of the relationship between pelvic prolapse and coexisting functional derangements. This may commonly require ancillary testing.

The role of preoperative imaging to detect hydronephrosis or ureteric compromise in the setting of advanced prolapse is controversial. Beverly et al. (1997) showed that the prevalence of hydronephrosis increases with worsening stage of prolapse. In women with severe prolapse, preoperative imaging may document preexisting hydronephrosis or ureteric obstruction that might otherwise be confused with iatrogenic ureteric injury at time of surgery. In addition, if preoperative radiographic studies demonstrate complete ureteric obstruction, a pessary with or without a ureteral stent may be placed if definitive surgery cannot take place promptly.

Some authors have not incorporated voiding diaries and urodynamics in their assessment because of the advanced age of their population and lack of compliance. In contrast, others advocate routine urodynamic testing in the setting of preoperative urinary symptoms or selective usage, depending on mitigating medical issues or excessive patient travel time. In a study by von Pechmann et al. (2003), 75 of 92 subjects underwent multichannel preoperative urodynamics; 36 (48.0%) had stress incontinence, 13 (17.3%) had detrusor overactivity, and 16 (21.3%) had mixed incontinence. Thus, treatment for clinical stress and urge incontinence must be incorporated into the treatment plan. In addition, FitzGerald and Brubaker (2003) found that 27% of patients without preoperative symptoms of stress incontinence developed new onset stress incontinence after surgery. Last, elderly patients with advanced prolapse are at higher risk for voiding dysfunction and retention when an anti-incontinence procedure, such as a suburethral sling, is performed.

LE FORT PARTIAL COLPOCLEISIS

An obliterative procedure in the form of a Le Fort partial colpocleisis is an option if the patient has her uterus and is no longer sexually active. Because the uterus is retained, it will be difficult to evaluate any future uterine bleeding or cervical pathology. Therefore, endovaginal ultrasound, endometrial biopsy, and Papanicolaou smear must be done before surgery. Denehy et al. (1995) reported two patients who were considered for a Le Fort procedure but were found to have stage IA endometrial carcinoma during the work-up phase.

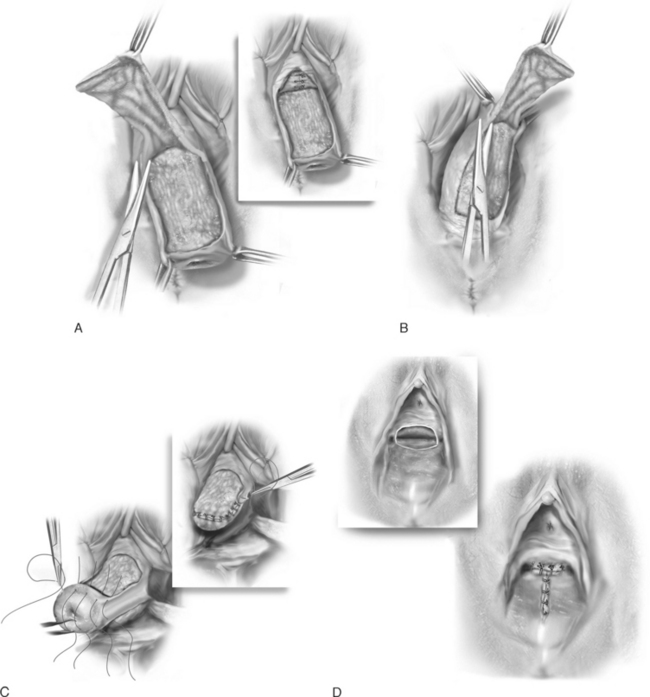

The previously marked areas are removed by sharp dissection (Fig. 22-1, A, B). The surgeon should leave the maximum amount of muscularis behind on the bladder and rectum. Hemostasis is an absolute must.

After reducing the cervix 3 to 4 cm, the cut edges of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls are sewn together with interrupted delayed absorbable sutures (Fig. 22-1, C). The knots should be turned into the epithelium-lined tunnels that were created bilaterally. The uterus and vaginal apex are gradually turned inward. After the vagina has been inverted, the superior and inferior margins of the incisions can be sutured together (Fig. 22-1, D). In the author’s opinion, a plication of the bladder neck should be routinely performed because of the high incidence of postoperative stress incontinence (Fig. 22-1, A, inset

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree