Eczematous Disorders

Susan Tofte

Eczematous inflammation, commonly referred to as “eczema,” is the most common of all inflammatory skin diseases. The term eczema actually comes from the Greek word “eczeo,” which literally means to effervesce or boil over, and presents as a papulovesicular, weeping dermatitis. Eczema is a generic or general term used to describe a variety of eczemas, including nummular eczema, contact or irritant dermatitis, xerotic (asteatotic) eczema, dyshidrotic (pompholyx), dermatophytids (Ids), or seborrheic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis (AD), although often incorrectly referred to as eczema, is a combination of eczema, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, known as the atopic triad.

In the most acute phase, eczema will appear intensely erythematous, often with vesicles which rupture, ooze, and become weepy. When secondary changes occur and eczema becomes less acute, erythema continues, but with increased scaling, excoriations, and sometimes fissures. Vesicles are usually dried at this stage. As eczema evolves into a chronic stage, the skin becomes lichenified with accentuated skin lines, the result of rubbing and scratching. Pruritus and evidence of scratching can be present at any stage, but is most intense during the acute stage when inflammation is more extreme. The skin barrier becomes more compromised with fissures and excoriations because of scratching, making it more susceptible to infection.

Histologic changes are similar in every stage of eczema, but vary depending on the degree of inflammation. Edema is most evident during the acute phase of eczema, revealing a high degree of spongiosis as well as larger numbers of lymphocytes. As eczema becomes chronic, histologic changes show more evidence of a thicker (lichenified) stratum corneum.

ATOPIC DERMATITIS

Many studies have been performed looking at the prevalence of AD in infants and children by using clinical evaluations, survey studies, and use of questionnaires coupled with clinical evaluation. These studies have been performed in Northern Europe, United States, and Japan, and prevalence of AD based on these studies is documented to be between 15% and 20% and is higher in children. Greater than 60% of AD cases develop during the first year of life; thus it is often referred to as a childhood disease. Although rare, it can present in adulthood. Research has shown that there is a strong concordance with monozygotic twins.

Quality of Life and Cost of Care

AD impacts not only the patient with the disease but impacts other family members, particularly parents who may find absences from work in order to stay home to care for their child affecting income and health benefits. Healthy siblings compete for attention and interface with parents, who find themselves consumed with the overwhelming task of caring for the child with AD. Research has suggested that caring for a child with type I diabetes mellitus is comparable to caring for a child with moderate-to-severe AD. Atopic dermatitis has more impact on the quality of life in childhood than any other childhood dermatoses with the exception of scabies. General pain and pruritus in any disease have a negative impact on the quality of life, but in AD when the pruritus is often intense and relentless, the negative burden is even greater, leading to disruptions in sleep, disruptions with play and recreational activities, as well as interference with normal social interactions and development. The economic impact of caring for a family member with AD has been compared to the cost of other chronic diseases such as emphysema or epilepsy. Within the past decade, the cost of care for AD was estimated to be over $ 300 million, with visits to the emergency room for acute extensive flares largely responsible for this cost.

Pathophysiology

AD is an inflammatory and xerotic skin disease. It is presumed that AD arises from genetic influence interfaced with environmental factors. There is a strong genetic association with epidermal barrier defects which encompass not only eczematous skin inflammation, but also allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and asthmatic influences. This trio, a combination of AD, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, is referred to as the “atopic triad.” An overproduction of IgE and cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 contribute to the inflammatory cascade of erythema, pruritus, and edema. Early age of onset, accompanied by respiratory allergy, and urban living may be predictors of more severe disease evolution. Very often children will outgrow the disease by the time they reach school age, but many continue to have the disease into adulthood where it may be localized to one area or region, such as the hands. This should be basic and fundamental, yet errors in bathing and moisturizing are the most common cause for persistent AD.

Epidermal Barrier Loss of Function

The ability for the skin barrier to absorb and hold water is essential in AD as well as in other xerotic skin diseases such as ichthyosis vulgaris. In the past 8 years, breakthrough research has uncovered filaggrin as a key protein in the normal skin barrier. Mutations of this essential protein for an intact skin barrier were found in the epidermis of patients with ichthyosis vulgaris as well as in patients with AD. These mutations represent a strong genetic predisposition for atopic eczema, asthma, and allergies.

Loss of filaggrin means a poorly formed stratum corneum and xerotic barrier that is prone to water loss and unable to protect the body. Xerosis leads to pruritus, which then promotes scratching and excoriations. As the skin barrier is further disrupted by prolonged itching and scratching, it becomes vulnerable to a host of potential infections and penetration of allergens that trigger IgE production.

Clinical Presentation

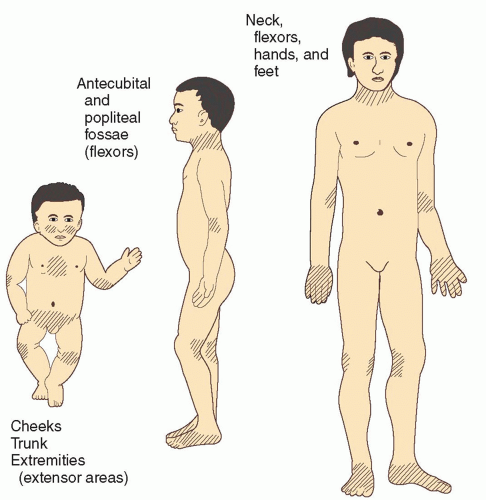

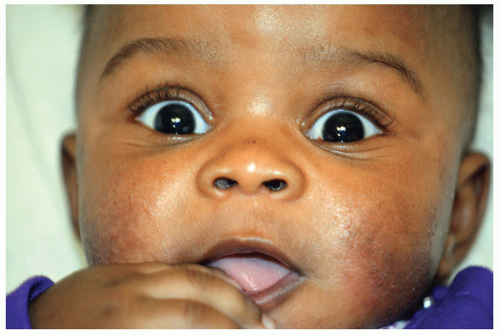

The hallmark of AD is pruritus, which is often intense and relentless, disrupting every aspect of the patient’s life. The course of AD tends to be chronic and relapsing. As an inflammatory skin disease, AD will present with varying degrees of erythema, inflammatory papules, which often coalesce to form eczematous plaques, as well as areas of weepy dermatitis. Often areas of involvement will evolve into scaly, xerotic plaques, and as the disease becomes chronic, lichenified changes are evident and indicative of extended periods of itching and scratching. Morphology and distribution vary with age (Figure 3-1). Typically in infants and very young children, AD will affect the face and extensor arms and legs (Figures 3-2 and 3-3A). The diaper region, where moisture tends to be retained, is often spared. In older

children and adults, distribution favors flexural areas, including anterior neck, antecubital fossa, and popliteal space, and can affect the breasts, nipples, and trunk (Figures 3-3B 3-3C, and 3-4). The scalp, face, and eyelids can also be affected, and in general, the axillae and groin folds are spared at any age.

children and adults, distribution favors flexural areas, including anterior neck, antecubital fossa, and popliteal space, and can affect the breasts, nipples, and trunk (Figures 3-3B 3-3C, and 3-4). The scalp, face, and eyelids can also be affected, and in general, the axillae and groin folds are spared at any age.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Atopic dermatitis

Tinea

Psoriasis

Nummular eczema

Contact dermatitis

Molluscum contagiosum dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis

Lichen simplex chronicus

Cutaneous T cell lymphoma, mycosis fungoides type

Diagnostics

AD is a clinical diagnosis with common cutaneous features used to diagnose AD (Box 3-1). Additionally, the diagnoses can only be made after exclusion of differential diagnoses (above) with similar presentations. A KOH test can differentiate tinea from AD. Punch biopsy will identify psoriasis and other noneczematous dermatoses.

Management

Bathing and moisturizing

Patients are often misinformed about bathing and become confused with directions about when and how often to bathe. Bathing is beneficial; it hydrates the skin, allows for added penetration of topically applied therapies, and can help debride crusts and scaling. Generally 20 minutes in a bath is ample time for the skin to become hydrated and to absorb the maximum amount of water. Bathwater should be warm or cool (not hot), and patients should be ready to apply a moisturizer or topical corticosteroid (TCS) (never both on the same area) within 3 minutes of exiting the tub. Both moisturizers and TCS should be applied immediately after soaking hydration, when the stratum corneum is soft and supple and penetration of the treatments is maximized. In the most severe cases where skin involvement is extensive, wet wraps may be useful as a substitute for a soaking bath for a few days until the skin has begun to heal and getting into water is more comfortable.

BOX 3-1 Clinical Criteria for a Diagnosis of Atopic Dermatitis

Essential features (both must be present)

Pruritus

Eczema (characteristic distribution and morphology)

Important features (support of the diagnosis of AD)

Early age of onset

Atopy (personal or family history, IgE reactivity) Xerosis

Associated features (suggests the clinician consider the diagnosis of AD)

Nipple eczema

Facial pallor, white dermographism, delayed blanching response

Keratosis pilaris

Ichthyosis

Hyperlinear palms

Periocular (Dennie-Morgan lines) and/or perioral changes, cheilitis

Perifollicular accentuation

Lichenification/prurigo lesions

Adapted from Eichenfield, L.F., Hanifin, J.M., Luger, T.A., Stevens, S.R., & Pride, H.B. (2003). Consensus conference on pediatric atopic dermatitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 49,1088-1095.

Emollients

Once AD is adequately controlled, moisturizers on a regular, daily, or several-times-daily basis are essential to maintain control. Emollients are the cornerstone of maintenance therapy and prevention of relapse. Greasy or creamy emollients are always recommended, and some creamy emollients with a lipid concentration may provide an even more durable barrier than other water-based creams. Lotions tend to contain increased amounts of water and alcohol and, upon evaporation, may actually cause more dryness. A helpful hint when discussing with a patient is to remind them that creamy or greasy products are, with few exceptions, found in jars rather than in pump bottles. The skin barrier is important to the pathogenesis of AD, and many research trials are focused on perfecting skin barrier function in order to see better therapeutic outcomes with less need for medication.

Medications

Topical corticosteroids. TCS are the first-line therapy for AD and remain the most effective therapy for obtaining swift control of a flare. There are a myriad of choices, but generally a mid- to highpotency corticosteroid such as triamcinolone 0.1% ointment, fluocinonide 0.05% ointment or betamethasone 0.05% ointment will adequately treat a flare. Creams can be used if patients insist, but ointments are always preferred. Typically a mid-strength corticosteroid is applied twice daily for 3 to 5 days on the thinner skin areas (face, eyelids, neck, breasts, and buttocks) and twice daily for 7 full days on the trunk and extremities. For practical reasons and to avoid confusion, it is best to prescribe one-strength TCS for all areas involved and to eliminate the risk of mistakenly using a stronger corticosteroid in a thin-skinned area. A mid-strength TCS can safely be used 2 days per week for long-term control and to prevent relapse.

Calcineurin inhibitors. There are two nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory topical medications approved for use in AD, tacrolimus ointment (Protopic) and pimecrolimus cream (Elidel).

Applied to the skin, calcineurin inhibitors modulate the body’s immune response in AD. Tacrolimus is available in two strengths 0.03%, which is approved for use in children aged 2 to 15 years, and 0.01%, which is approved for ages 15 years and older; and it is compounded in an ointment vehicle and prescribed for moderate-to-severe AD. Pimecrolimus is compounded in a cream vehicle with one strength and is prescribed for ages 2 and older with mild-to-moderate AD. Often calcineurin inhibitors are used for maintenance once the disease flare has been controlled with the use of a TCS first in the more acute stages of the flare. The cutaneous side effects of burning, itching, and stinging can be accentuated on flared skin and uncomfortable for patients, which may lead to noncompliance of the medication. Combination therapy of a mid-strength TCS 2 days per week and calcineurin inhibitors 5 days per week is a practical and effective plan to induce a remission, then for maintaining control of atopic disease.

Applied to the skin, calcineurin inhibitors modulate the body’s immune response in AD. Tacrolimus is available in two strengths 0.03%, which is approved for use in children aged 2 to 15 years, and 0.01%, which is approved for ages 15 years and older; and it is compounded in an ointment vehicle and prescribed for moderate-to-severe AD. Pimecrolimus is compounded in a cream vehicle with one strength and is prescribed for ages 2 and older with mild-to-moderate AD. Often calcineurin inhibitors are used for maintenance once the disease flare has been controlled with the use of a TCS first in the more acute stages of the flare. The cutaneous side effects of burning, itching, and stinging can be accentuated on flared skin and uncomfortable for patients, which may lead to noncompliance of the medication. Combination therapy of a mid-strength TCS 2 days per week and calcineurin inhibitors 5 days per week is a practical and effective plan to induce a remission, then for maintaining control of atopic disease.

In 2003, after both tacrolimus and pimecrolimus were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in AD, a black-box warning was issued about the possible risk of cancer in both children and adults. The warning was based on sporadic spontaneous case reports of skin cancers in adults and lymphomas in children. To date there has been no statistical evidence linking development of cancer and the use of these topical agents, and short-term data on systemic side effects for both drugs are reassuring. Long-term safety data are ongoing. For this reason, the calcineurin inhibitors have been given the designation of second-line therapy, while TCS remain as first-line therapy for AD.

Antihistamines. Sedating antihistamines such as diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine can be helpful for their somnolent effect when taken at bedtime. They can help promote more restful sleep and help reduce scratching during the night and perhaps help to avoid children cosleeping with parents. Nonsedating antihistamines can be helpful for patients who suffer from allergic rhinitis, but should not be prescribed as an antipruritic treatment. Topical antihistamines are generally not recommended as they can be irritating to atopic skin and have the potential to cause allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

Antibiotics. Oral antibiotics are needed to treat Staphylococcus aureus skin infections, which are commonly seen in patients with AD. Generally 5 days of cephalexin or dicloxacillin are adequate to treat a staph infection. Overuse of antibiotics potentially leads to methicillin-resistant S. aureus in AD patients and should be avoided. In patients who have frequent or recurring staph infections, addition of rifampin for 10 days or taking tetracycline for 30 days in conjunction with topical mupirocin may help halt the chronic nature of the infections. It is important for patients to recognize the signs of a skin infection and to know that it is often the reason for a flare, and if left untreated, their flare-up is likely to persist. Topical antibiotics such as polysporin or mupirocin can be used when the infection is localized and the skin is not flaring. If the patient develops recurrent skin infections, bleach baths can be helpful to decolonize the skin (onequarter cup of bleach to a full tub for pediatric patients, one-half cup for adults). Culturing for sensitivities to rule out methicillin-resistant S. aureus is always advised if the patient does not to respond to standard antibiotic therapy.

Management of Severe and Extensive Disease

When flares are severe and extensive, oral corticosteroids may be necessary to regain control. Generally, a tapering dose of prednisone over the course of 6 days is adequate with the addition of a TCS at the end of the taper. In patients with recalcitrant disease, a course of cyclosporine (CSA) can be utilized. This is generally prescribed when intense topical therapy and/or courses of prednisone have not halted the AD flare. Baseline labs of chemistry panel, complete blood count, and urinalysis need to be obtained prior to starting this therapy and monitored monthly. Blood pressure is also monitored regularly. Due to the potential for renal toxicity and hypertension, it is not a therapy that can be used indefinitely, and after a 6-month course, transition to another therapy is warranted. Patients with known renal disease or uncontrolled hypertension should not take CSA. The starting dose of CSA when prescribed is usually at 5 mg/kg/day. This dose will quickly reduce both pruritus and inflammation and induce a remission, giving patients worn down by their disease a reprieve. After 6 months of therapy, transition to another therapy is usually indicated. Ultraviolet therapy or other systemic therapies, including methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and interferon-γ, have shown varying levels of efficacy in AD patients.

Prognosis and Complications

It is important for AD patients to recognize possible extrinsic factors that may trigger a flare of their skin disease. Common trigger factors for AD flares are any type of infection, including viral, bacterial, fungal, and yeast infections (Figures 3-5A and B). Counseling patients to recognize signs of infection and treating quickly is important. Primary outbreaks of herpes simplex virus (HSV) can result in eczema herpeticum (Figure 3-5C). Treating HSV with acyclovir 400 mg t.i.d. for 1week is adequate; however, treatment for eczema herpeticum should include zoster doses of antivirals. Checking for tinea when AD is flaring should be part of your physical exam. Checking toe web spaces, groin, and other intertriginous areas is important when looking for causes of a continued flare. Widespread fungal infections may need treatment with a systemic antifungal. Stress, dry climate, allergic reactions are also potential triggers. AD can severely impact a patient’s (and their caregivers) quality of life and should be discussed with the patient. Abnormal pigmentation, lichenification, scars, striae, and secondary infections are complications from AD (Figure 3-5D).

Referral and Consultation

Severe AD patients require enormous amounts of clinic time to gain control of their disease. Psychological factors are often addressed, as are sleep, trigger factors, explanation of treatments, side effects, and detailed instructions regarding use of medications. An AD patient who becomes erythrodermic will need inpatient hospitalization. A referral to a dermatologic professional who specializes in atopic disease is appropriate. The National Eczema Association (NEA) is a nonprofit patient-centered organization for patients and their families. They offer a host of valuable educational information and support for families as well as for health care professionals.

Patient Education and Follow-up

AD patients require long periods of time and educational dialogue in order to understand the fundamentals of how to manage flares, then maintain control of the disease, and how to recognize signs of skin infections. Compliance to treatment plans is essential for maintenance once the skin disease is under control. Ideally a dermatology nurse will be involved in the teaching and demonstration of treatments, as this can be a time-consuming process that may not automatically be built into the providers’ schedule. Studies have shown that nurse-led clinics help reduce the severity of AD outcomes in children and compliance increase up to 800%.

NUMMULAR ECZEMA

Nummular eczema (nummular or discoid dermatitis) is a common and chronic skin disorder characterized by its annular or round, “coin shaped” lesions. Nummular eczema can, and often does, overlap with AD, stasis dermatitis, and asteatotic eczema. Males are more affected than females; and the age of onset is over 50 years for males but earlier for females around 30 years.