Chapter 4

Eczema (Dermatitis)

OVERVIEW

- Eczema describes a pattern of inflammation in the skin caused by a multitude of causes.

- Eczema includes atopic dermatitis, contact allergy, varicose eczema, pompholyx and discoid eczema.

- Atopic dermatitis affects about 3% of infants and can lead to considerable morbidity to the child and the family.

- Management relies heavily on regular applications of emollients and topical steroids.

Eczema and dermatitis are terms used to describe the characteristic clinical appearance of inflamed, dry, occasionally scaly and vesicular skin rashes associated with divergent underlying causes. The word eczema is derived from Greek, meaning ‘to boil over’, which aptly describes the microscopic blisters occurring in the epidermis at the cellular level. Dermatitis, as the term suggests, implies inflammation of the skin which relates to the underlying pathophysiology. The terms eczema and dermatitis encompass a wide variety of skin conditions usually classified by their characteristic distribution, morphology and any trigger factors involved.

Clinical features

Eczema is an inflammatory condition that may be acute or chronic. Acute eruptions are characterised by erythema, vesicular/bullous lesions and exudates. Secondary bacterial infection (staphylococcus and streptococcus) heralded by golden crusting may exacerbate acute eczema. Chronicity of inflammation leads to increased scaling, xerosis (dryness) and lichenification (thickening of the skin where surface markings become more prominent). Eczema is characteristically itchy and subsequent scratching may also modify the clinical appearance leading to excoriation marks, loss of skin surface, secondary infection, exudates and ultimately marked lichenification (Figure 4.1). Inflammation in the skin can result in disruption of skin pigmentation causing post-inflammatory hyper/hypopigmentation. Patients often fear that loss of pigment is due to the application of topical steroids but in the majority of cases it is due to chronic inflammation.

Figure 4.1 Chronic atopic dermatitis.

Pathophysiology

The underling causes of endogenous dermatitis are poorly defined; however, genetic predisposition is common in patients with atopic dermatitis. In these patients there is an abnormality in the balance of T-helper lymphocytes, leading to increasing numbers of Th-2 cells compared to Th-1 and Th-17. The abnormal Th-2 cells interact with Langerhans cells, causing raised levels of interleukins/IgE and a reduction in gamma interferon with resultant upregulation of pro-inflammatory cells. In addition to this, immune dysregulation gene defects have been identified in large cohorts of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) including filaggrin gene defects which lead to impaired skin barrier function. This impaired barrier leads to increased transepidermal water loss and increased risk of antigens and infective organisms entering the skin.

Pathology

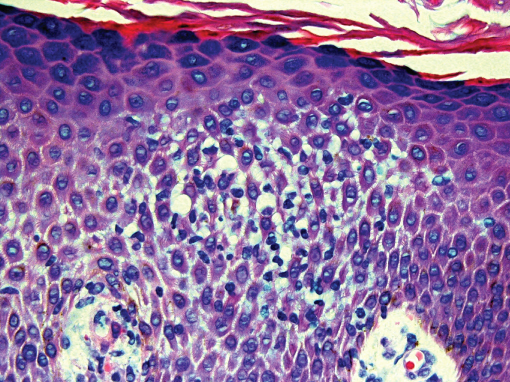

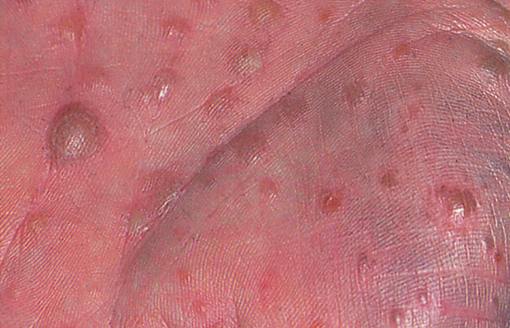

The clinical changes associated with dermatitis are reflected accurately at the cellular level. There is oedema in the epidermis leading to spongiosis (separation of keratinocytes) and vesicle formation. The epidermis is hyperkeratotic (thickened) with dilated blood vessels and an inflammatory (eosinophil) cell infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Histology of eczema.

Types of eczema

Eczema is classified broadly into endogenous (constitutional) and exogenous (induced by an external factor).

Endogenous eczema

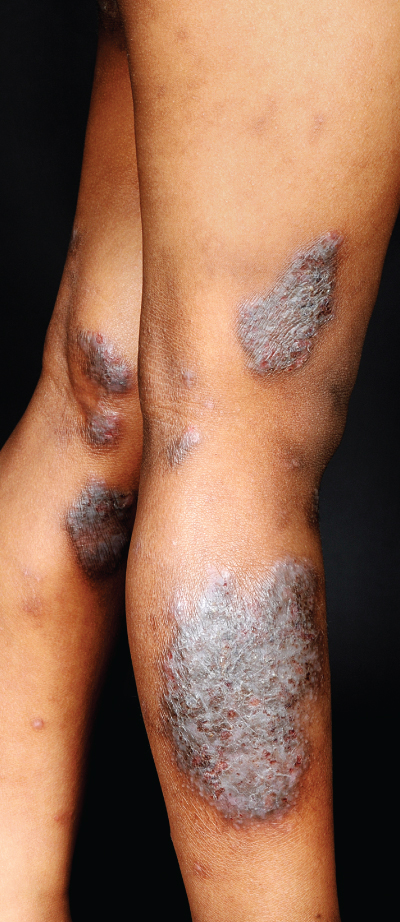

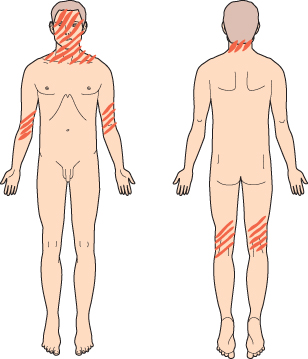

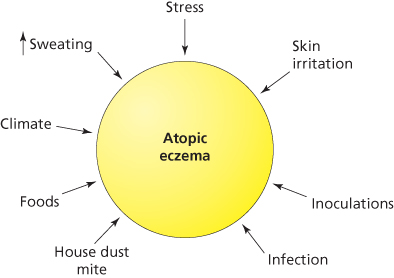

AD typically presents in infancy or early childhood, initially with facial (Figure 4.3) and subsequently flexural limb involvement (Figures 4.4 and 4.5). AD is intensely itchy, and even young babies become highly proficient at scratching, which can lead to disrupted sleep (both patient and family), poor feeding and irritability. The usual pattern is one of flare-ups followed by remissions, exacerbations being associated with inter-current infections, teething, and food allergies. In severely affected babies failure to thrive may result. In older children or adults, AD may become chronic and widespread and is frequently exacerbated by stress. AD is common, affecting 3% of infants; nonetheless, 90% of the patients spontaneously remit by puberty. Patients likely to suffer from chronic AD in adult life are those who have a strong family history of eczema, present at a very young age with extensive disease and have associated asthma/multiple food allergies (Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.3 Facial atopic dermatitis.

Figure 4.4 Chronic lichenified eczema on the legs.

Figure 4.5 Distribution of atopic dermatitis.

Figure 4.6 Factors leading to the development of atopic dermatitis.

Pityriasis alba is a variant of atopic eczema in which pale patches of hypopigmentation develop on the face of children. Juvenile plantar dermatosis is another variant of atopic eczema in which there is dry cracked skin on the forefoot in children (Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7 Plantar dermatitis.

Eczema herpeticum is herpes simplex viral infection superimposed onto the skin affected by eczema (usually in atopics). There is frequently a history of close contact with an adult with herpes labialis (cold sore). Clinically, there are multiple small ‘punched-out’ looking ulcers, especially around the neck and eyes (Figure 4.8). Eczema herpeticum is a serious complication of eczema that may be life threatening, and therefore early intervention with systemic aciclovir is essential under the guidance of a dermatology specialist.

Figure 4.8 Eczema herpeticum.

Lichen simplex is a localised area of lichenification produced by rubbing (Figure 4.9).

Figure 4.9 Lichen simplex.

Asteatotic eczema occurs in older people with dry skin, particularly on the lower legs. The pattern on the skin resembles a dry river-bed or ‘crazy-paving’ (Figure 4.10).

Figure 4.10 Asteatotic eczema.

Discoid eczema appears as intensely pruritic coin shaped lesions most commonly on the limbs (Figure 4.11). Lesions may be vesicular and are frequently colonised by Staphylococcus aureus. Males are more frequently affected than females.

Figure 4.11 Discoid eczema.

Pompholyx eczema is itching vesicles on the fingers, palms and soles. The blisters are small, firm, intensely itchy and occasionally painful (Figure 4.12). The condition is more common in patients with nickel allergy.

Figure 4.12 Pompholyx eczema.

Venous (stasis) eczema is a common insidious dermatitis that occurs on the lower legs of patients with venous insufficiency. These patients have back flow of blood from the deep to the superficial veins leading to venous hypertension. In the early stages, there is brown haemosiderin pigmentation of the skin, especially on the medial ankle, but as the disease progresses skin changes can extend up to the knee (Figure 4.13). Patients typically have peripheral oedema, and ulceration may result. The mainstay of management is compression (see Chapter 11).

Figure 4.13 Varicose eczema.

Investigations of eczema

Skin swabs should be taken from the skin if secondary bacterial (Figure 4.14) or viral infection is suspected. The swab should be moistened in the transport medium before being rolled thoroughly on the affected skin, coating all sides of the swab to ensure an adequate sample is sent to the laboratory. A significant growth of bacteria reported with its sensitivity and resistance pattern can be useful in guiding antibiotic usage. Nasal swabs should be performed in older children and adults with persistent facial eczema to check for nasal Staphylococcus carriage. If a secondary fungal infection is suspected then scrapings or brushings can be taken for mycological analysis.

Figure 4.14 Infected eczema.

Routine blood tests are not necessary; however, an eosinophilia and raised immunoglobulin E (IgE) level may be seen. RAST (radioallergosorbent testing) looks for specific IgE levels against suspected allergens such as aeroallergens (pollens, house dust mite and animal dander) and foods (egg, cow’s milk, wheat, fish, nuts and soya proteins). Skin prick testing may also be used to determine any specific allergies to aeroallergens or foods.

Skin biopsy (usually a punch biopsy) for histological analysis may be performed if the diagnosis is uncertain. Beware unilateral eczema of the areola, which could be Paget’s disease of the nipple (Figure 4.15).

Figure 4.15 Paget’s disease of the nipple—beware unilateral ‘eczema’.

Varicose eczema (leg ulcer) patients should have their ABPI (ankle brachial pressure index) measured before compressing their legs with bandages. ABPI is the ratio of their arm:ankle systolic blood pressure.

Classification of eczema

| Endogenous (constitutional) eczema | Exogenous (contact) eczema | Secondary changes |

| Atopic | Irritant | Lichen simplex |

| Discoid | Allergic | Asteatotic |

| Pompholyx | Photodermatitis | Pompholyx |

| Varicose | Infection | |

| Seborrhoeic (discussed later) |

Exogenous eczema

Contact dermatitis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree