Ear

ANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS

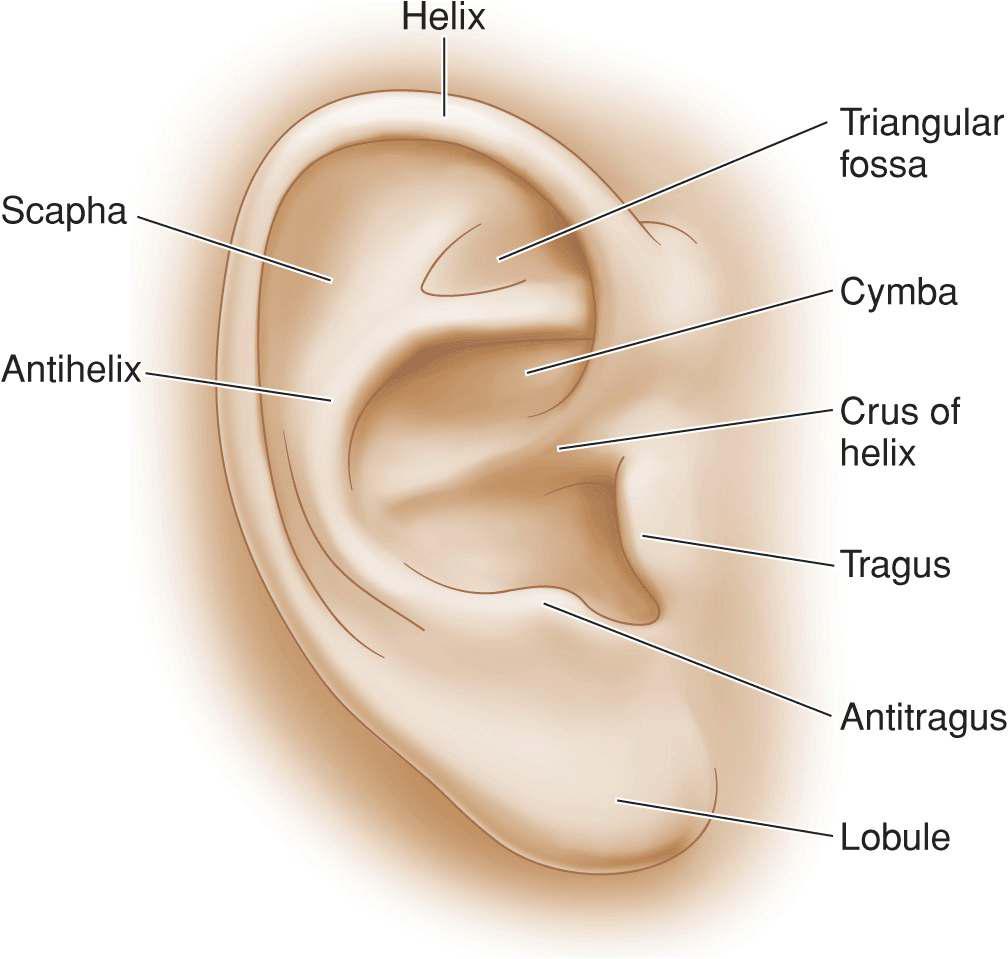

The ear is a complex cartilaginous structure enveloped by a thin fascia. The anterior surface is highly convoluted with a rich topography (Fig. 8.1). The skin here is stretched tight like a drum and provides minimal resource for adjacent tissue transfer. The helical rim creates a sharp reflection posterior to which the skin and subcutaneous tissues are somewhat thicker, more richly vascular, and mobile. The lower helix and lobule contain abundant fat and are loose and freely mobile. Toward the reflection with the mastoid scalp, the ear receives tendinous muscular fibers from the auricular musculature which are more adherent to the perichondrium.

Figure 8.1 Nomenclature of the ear

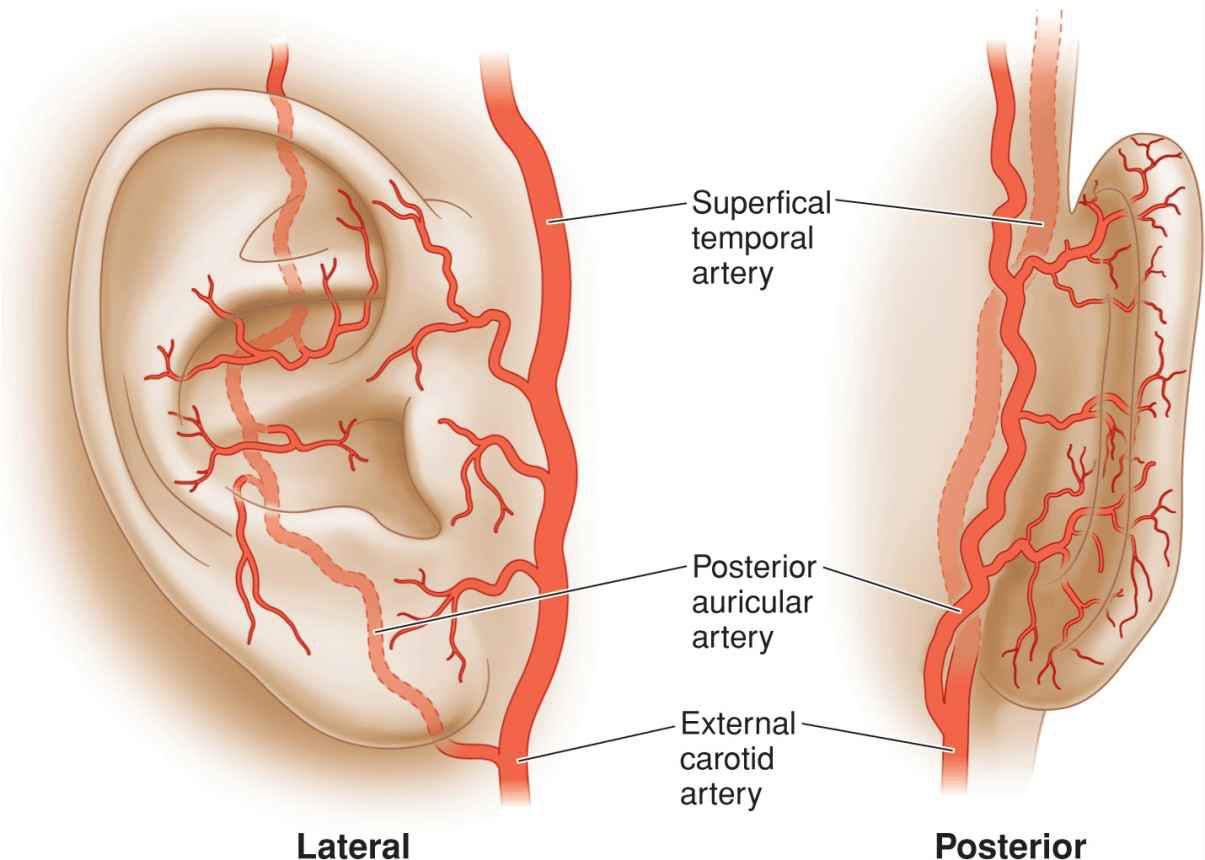

The vascular supply of the ear is rich and redundant (Fig. 8.2). The majority of the posterior surface of the ear and the lobule are supplied by branches of the posterior auricular artery, a direct branch off of the external carotid. The superior helical rim, the triangular fossa, and the scapha are supplied by a superior auricular branch off of the superficial temporal artery. The conchal bowl is largely supplied by perforators from the posterior auricular artery.

Figure 8.2 Arterial supply of the ear

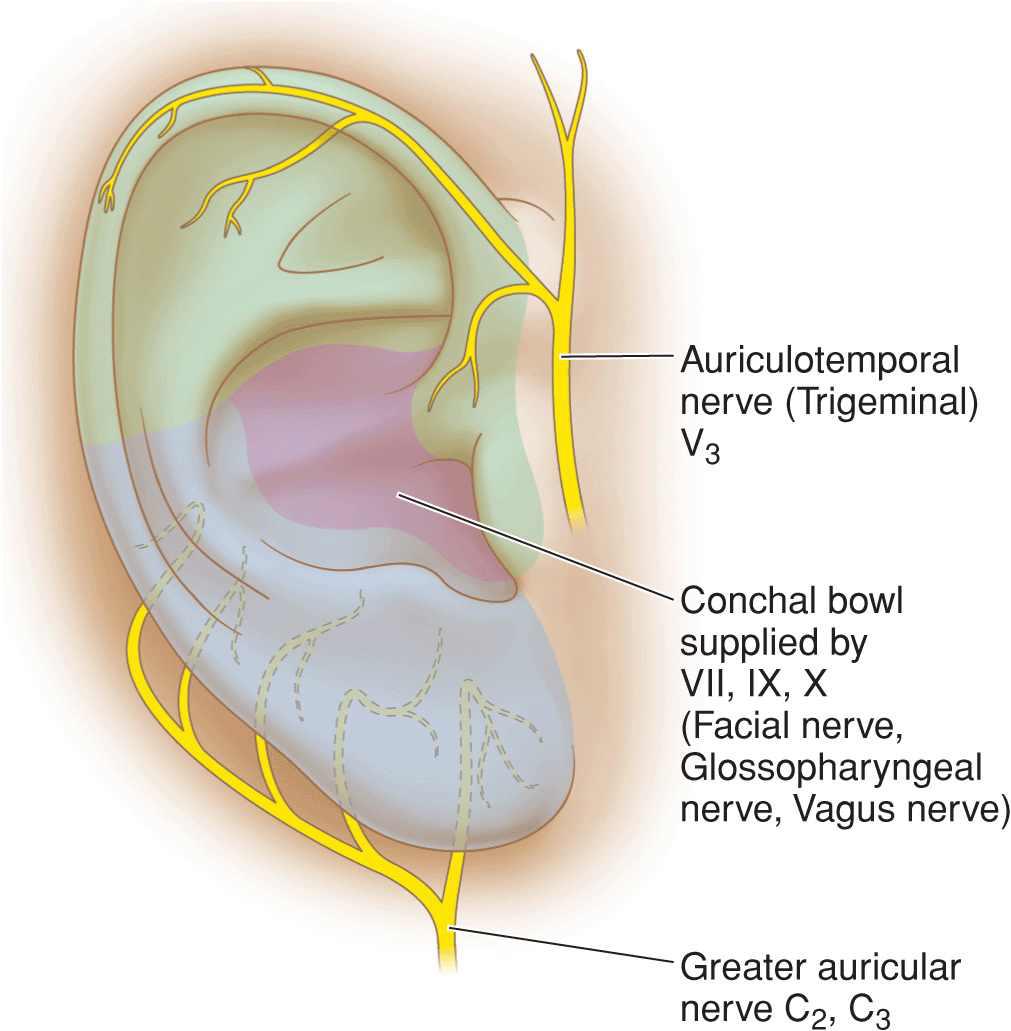

Sensory innervation of the ear is from three sources (Fig. 8.3). The majority of the ear is innervated from the greater auricular nerve that arises from the second and third cervical nerves and passes over the sternomastoid to arrive at the ear right at the base of the lobule. Portions of the anterior surface of the ear and superior ear are innervated by the auriculotemporal nerve, which is a direct branch from the mandibular nerve of the fifth cranial nerve. The inner conchal bowl and outer canal derive sensory input from cranial nerves VII, IX, and X.

Figure 8.3 Sensory innervation of the ear

Repair of the ear is indicated both for aesthetics, and for structural and functional integrity. The upper helix holds our glasses, and the integrity of the conchal bowl is important for the wearing of a hearing aide. The shape of an ear and its size relative to the contralateral ear are less important in terms of symmetry than of the nose, perioral and periocular region. However, a helix with a notch in it may be aesthetically displeasing, and sharp edges of cartilage with inadequate cutaneous coverage can be substantially painful and predisposed to chondrodermatitis nodularis helices. Because of the innate complexity of the ear and the lack of available local tissues, reconstruction of the ear requires creativity.

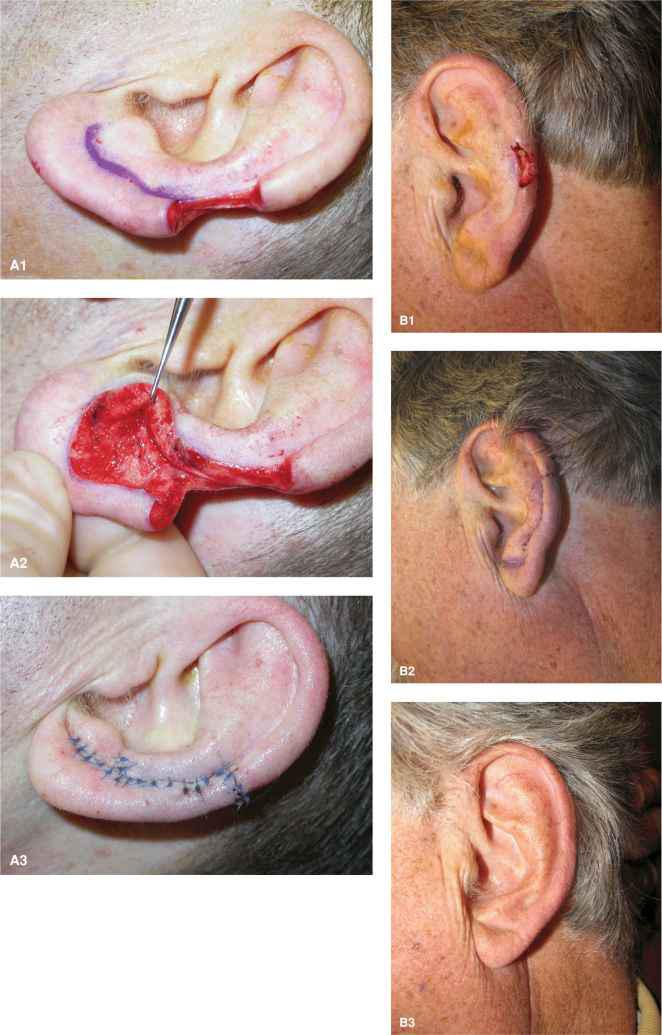

SKIN GRAFTS AND SECOND INTENTION HEALING

While this is a text about adjacent tissue transfer, no discussion of ear reconstruction is reasonable without addressing healing by second intention and the use of skin grafts. Moderate wounds of the ear on the anterior or posterior pinna with preserved perichondrium will heal well by second intention. If cartilage is exposed, removal of the underlying cartilage followed by healing from the opposing perichondrium will speed healing and prevent chondritis. Broad wounds of the anterior pinna and helical rim are resurfaced beautifully with skin grafts (Fig. 8.4). Appropriate donor sites are the preauricular skin, postauricular sulcus, mastoid, or neck. Such grafts should be appropriately thinned. A larger graft resurfacing the ear is often remarkably aesthetically pleasing, often to the point of near invisibility. For this reason, grafts should be strongly considered when the cartilaginous structure of the ear is intact and the perichondrium is preserved. Even in cases with some loss of cartilage along the helical rim, a skin graft will function well.

Figure 8.4 Full-thickness skin grafts are excellent repairs on the ear for wounds with preserved perichondrium. (A1-A3) A large defect of the anterior surface of the ear is repaired with a postauricular full-thickness skin graft. The repair is shown immediately and at 6 months. (B1-B3) An extensive defect of the conchal bowl and canal is repaired with a preauricular full-thickness skin graft. While this area may heal by second intention, a skin graft prevents webbing and contraction of the operative wound. The follow-up is at 6 months. (C) Defects of the outer helix are reliably and superiorly resurfaced with a full-thickness skin graft. The repair is shown immediately and at 6 months

FLAP RECONSTRUCTIONS

Defects of the Helical Rim

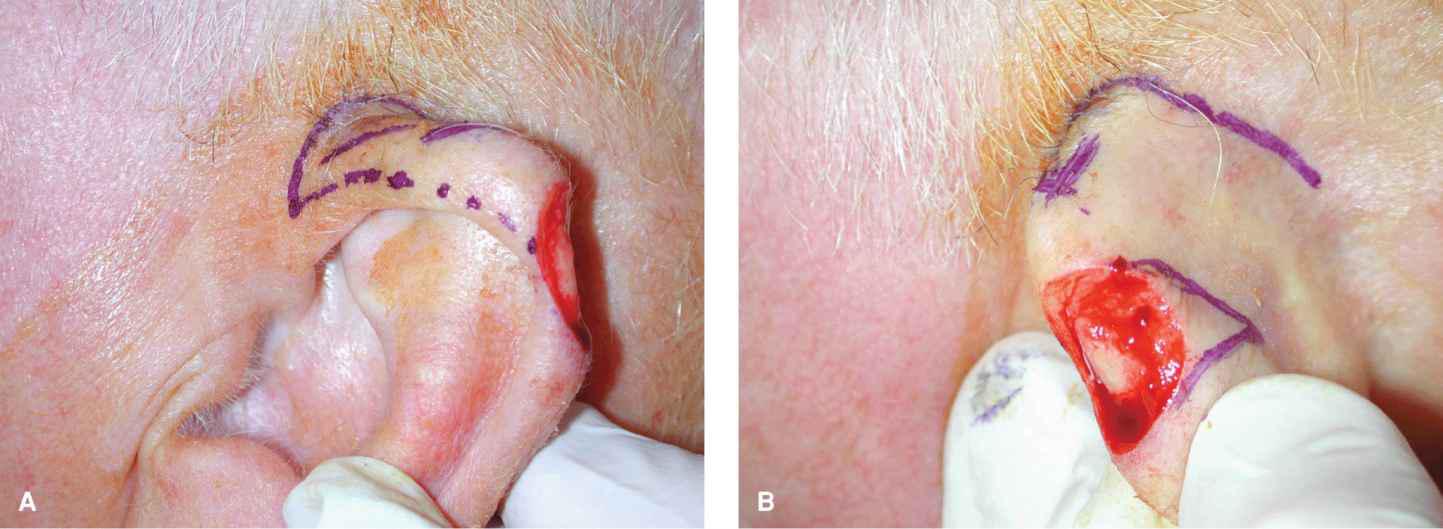

Ear wedge

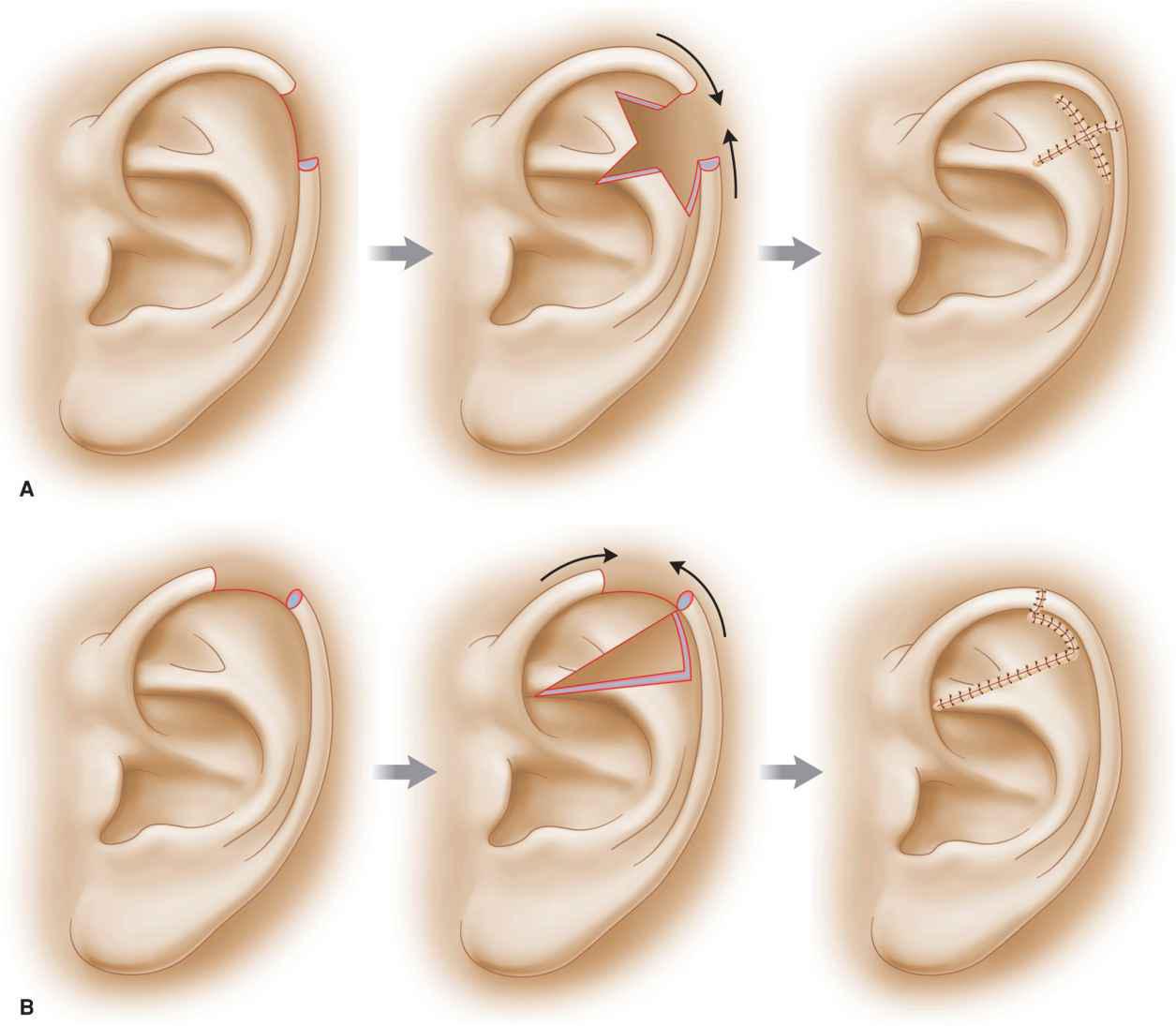

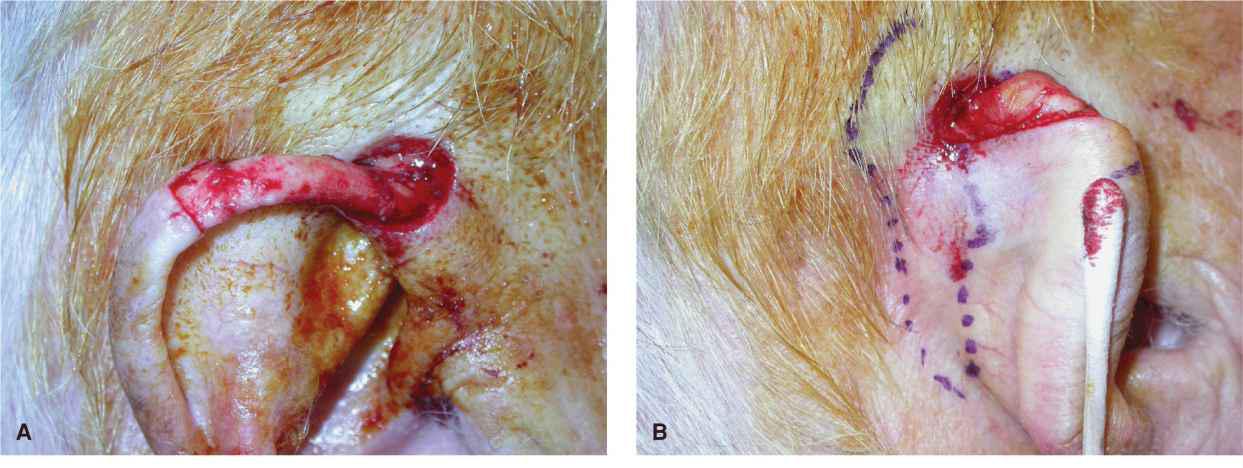

In most cases of aesthetic reconstruction of the ear, the ear wedge is the least attractive reconstruction option. However, in patients with low cosmetic requirements and a small to moderate dog-bite-type wound of the helix and outer pinna, a simple wedge can be appropriate. The most successful ear wedge is not a simple V-shaped repair but rather a star-shaped repair, or a staggered/ modified wedge (Figs. 8.5 and 8.6).1–4 The star wedge allows for the cartilage to close without buckling. The wedge is accomplished by excising the star shape full thickness and closing in a multilayered fashion. The ear cartilage may be sutured together with standard absorb-able sutures, but suturing of cartilage should be limited in scope. Care should be taken to place knots on the posterior surface so that they are covered by a thicker dermis and epidermis. The dermis and epidermis should be repaired with surface sutures only, as deep sutures will tend to form suture reactions. It can be surprising how much cartilage needs to be removed in order to close a helical wound with a star-shaped wedge.

Figure 8.5 Modest full-thickness wounds of the ear may be repaired with a star-shaped ear wedge reconstruction. (A) A bite-like wound of the helix and pinna may be repaired by designing a wedge with a star-shaped removal of cartilage. (B) A modification of the ear wedge is an offset or staggered ear wedge. The dog-ear(s) are removed at a distance from the operative wound. This can assist with avoiding anterior cupping of the ear at closure

Figure 8.6 A sizeable bite-like wound of the ear is repaired with a wedge. A large amount of cartilage has been removed in order to prevent cupping of the ear. While the ear is made smaller with a wedge reconstruction, this is rarely noticed at a conversational distance. (A) Moderate full-thickness wound of the ear. (B) Immediate closure with a foreshortened ear. A large star of cartilage has been removed. (C) Closure at 1 year with excellent contour, but a smaller ear

When larger wounds of the ear are repaired with a wedge closure, the ear tends to cup or buckle anteriorly. This can occur regardless of the amount of cartilage resected, and for that reason, it is worthwhile to avoid the ear wedge in most reconstructions.

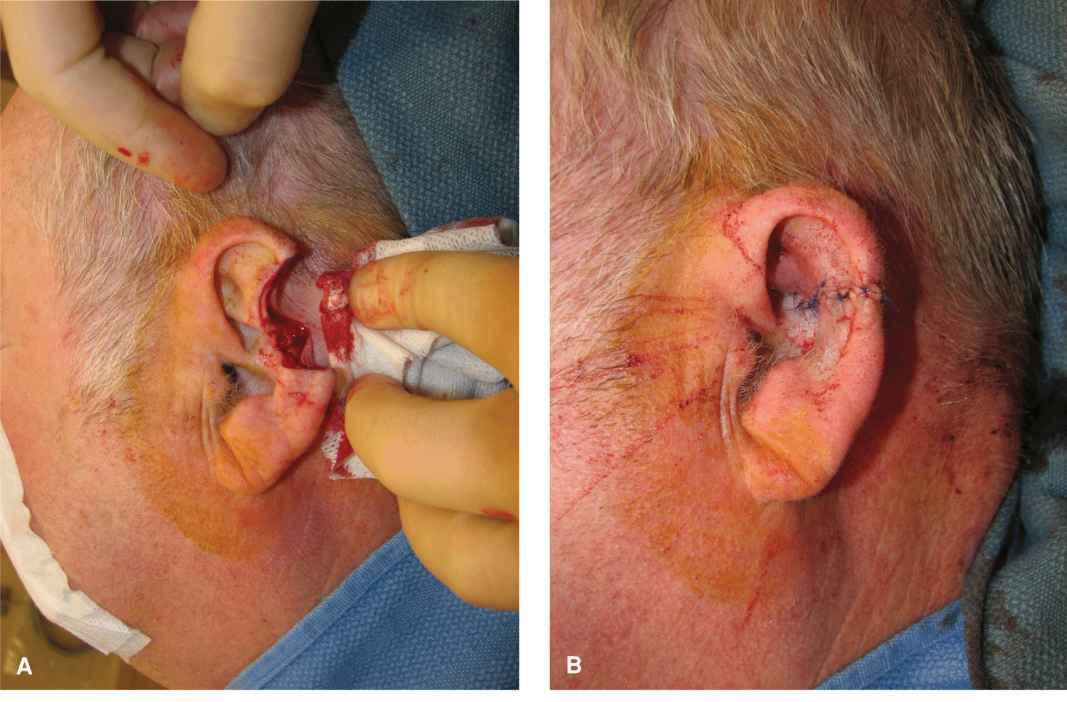

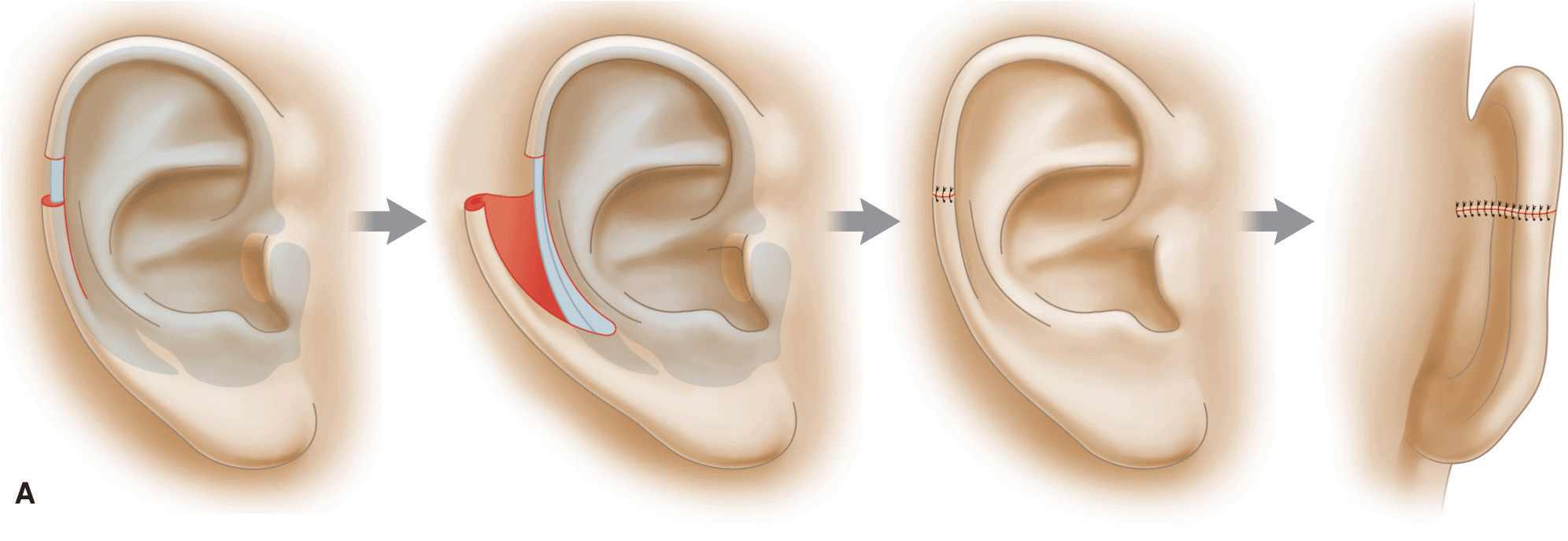

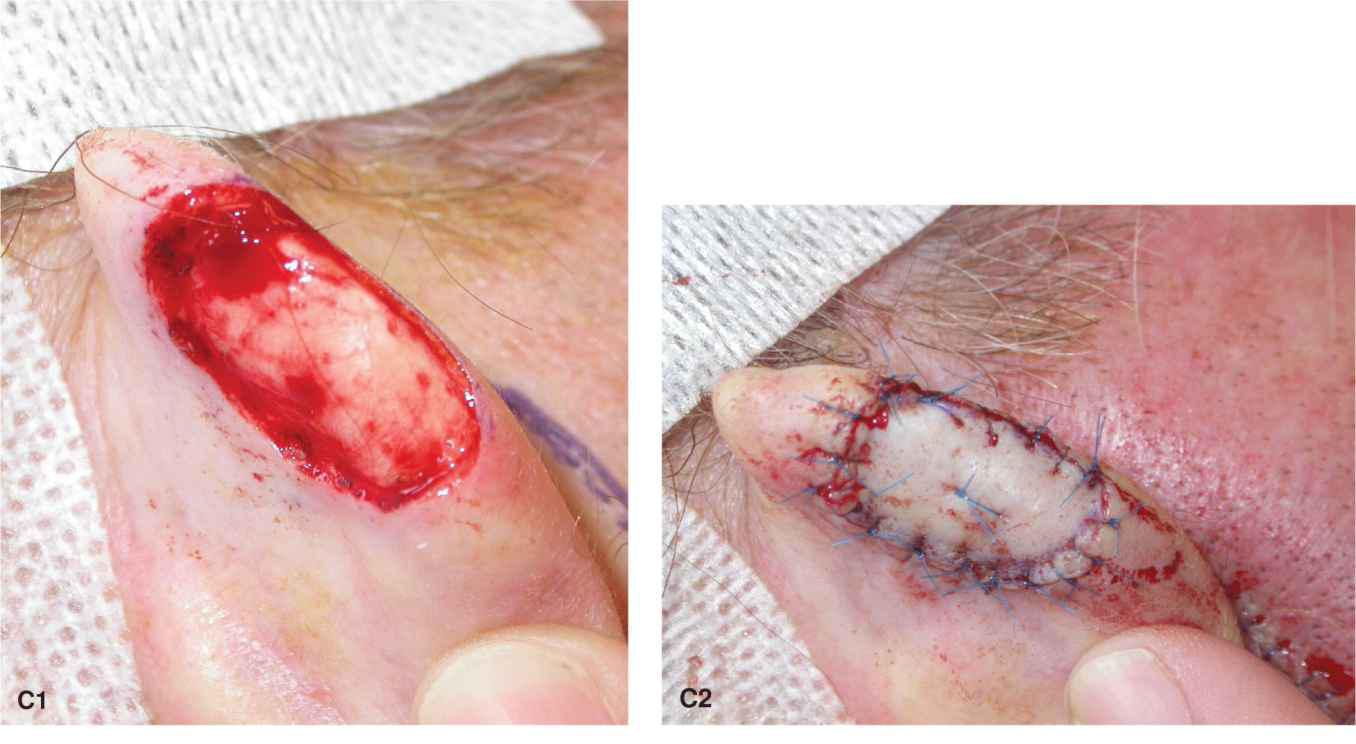

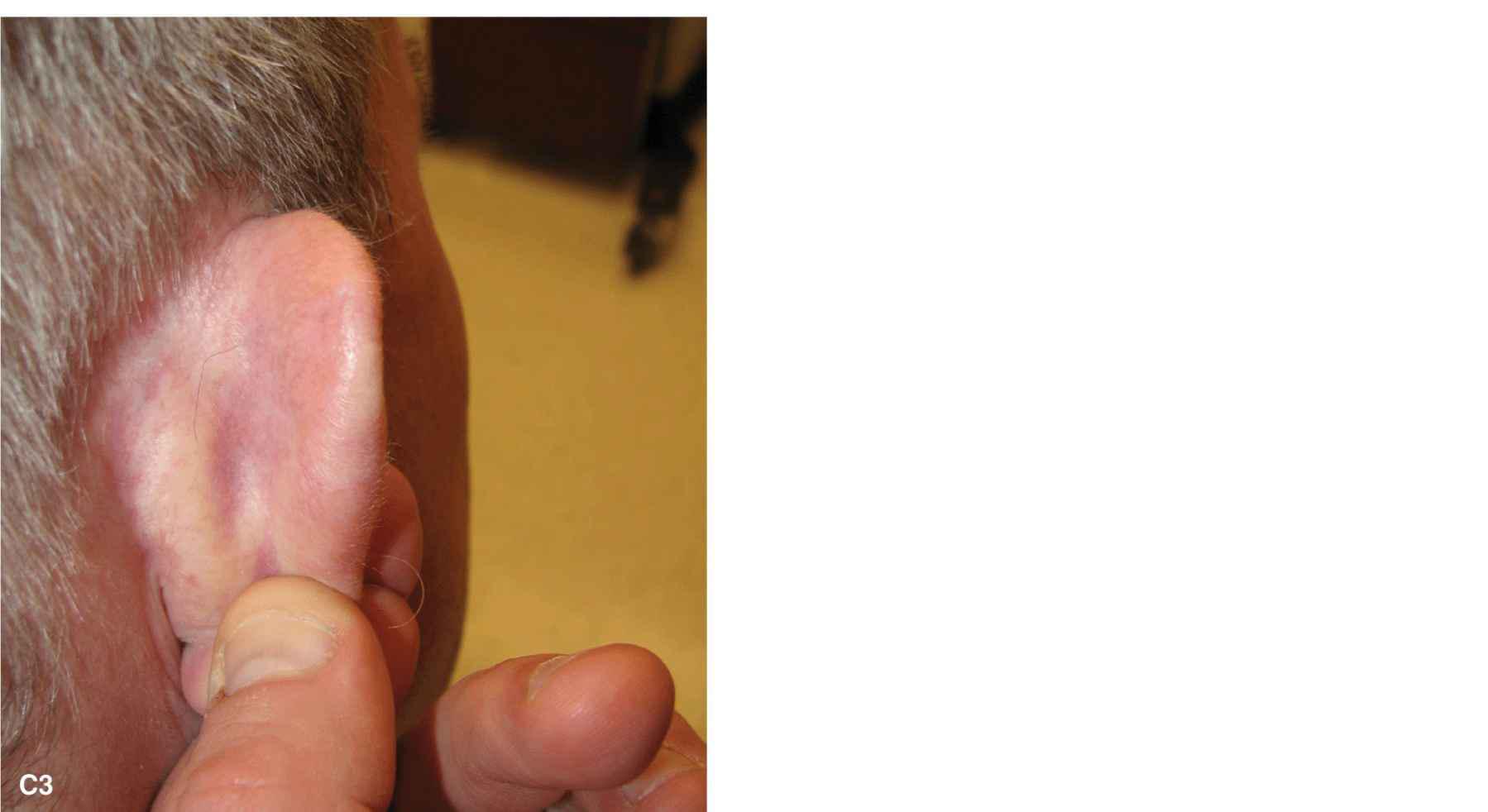

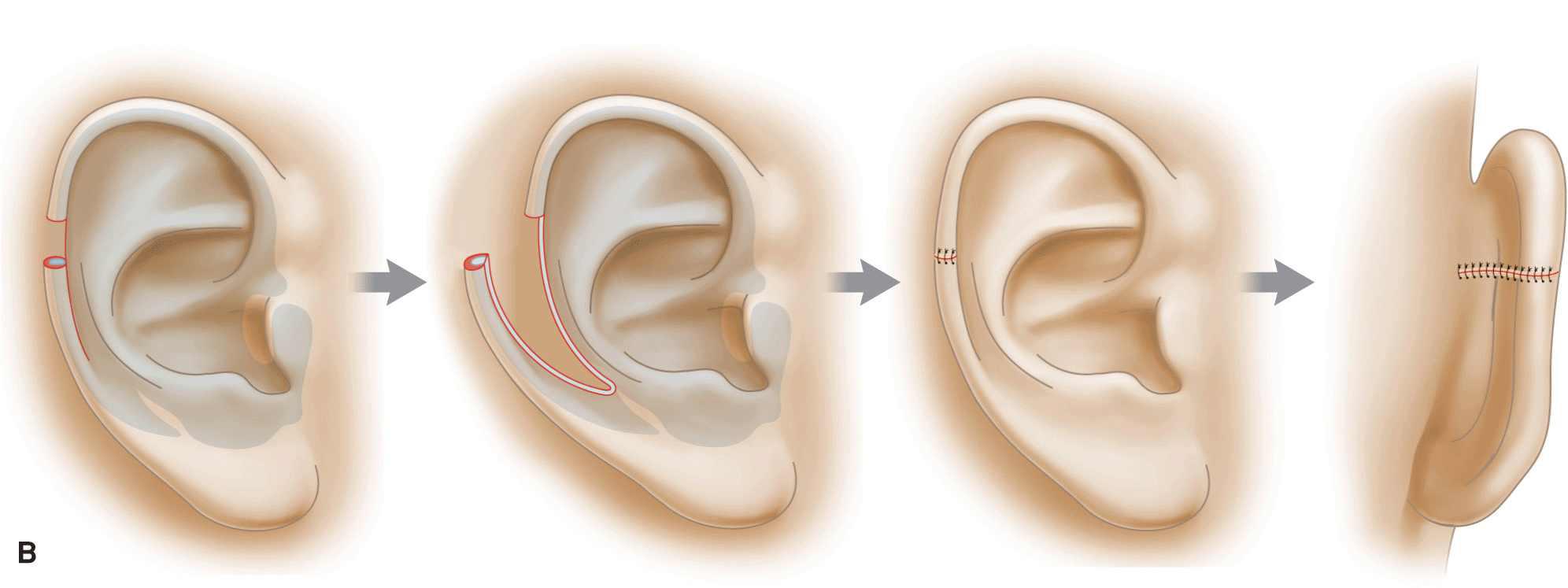

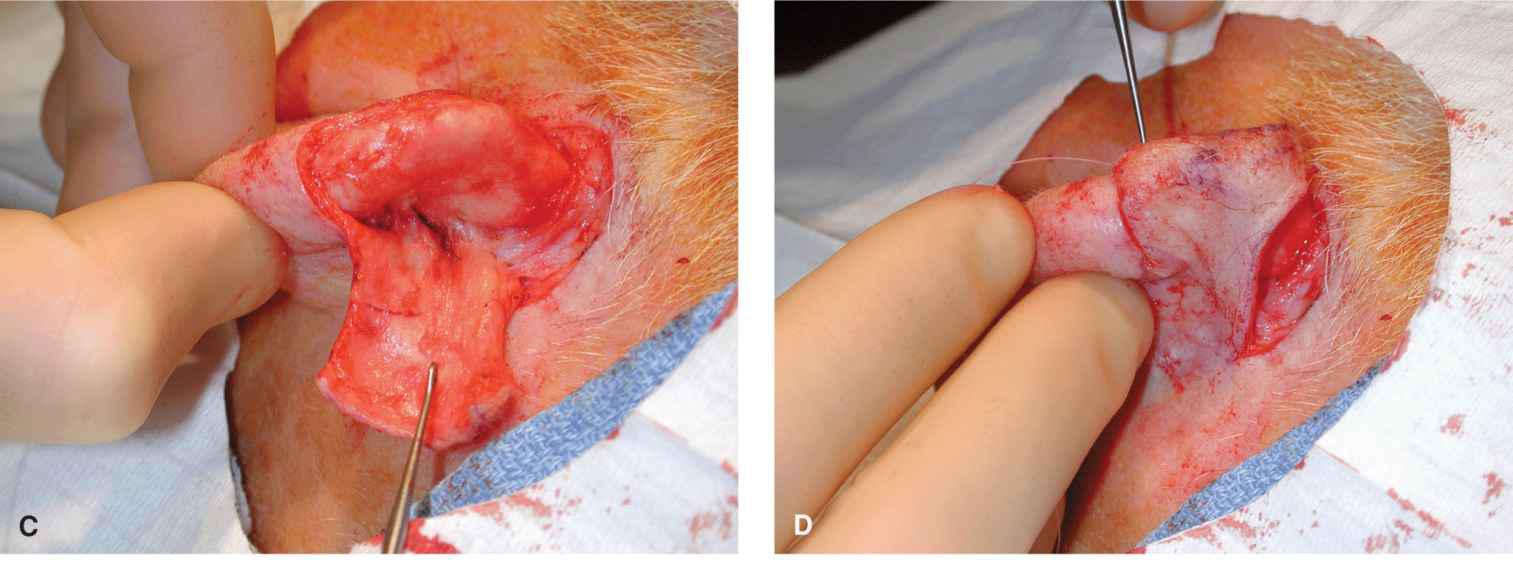

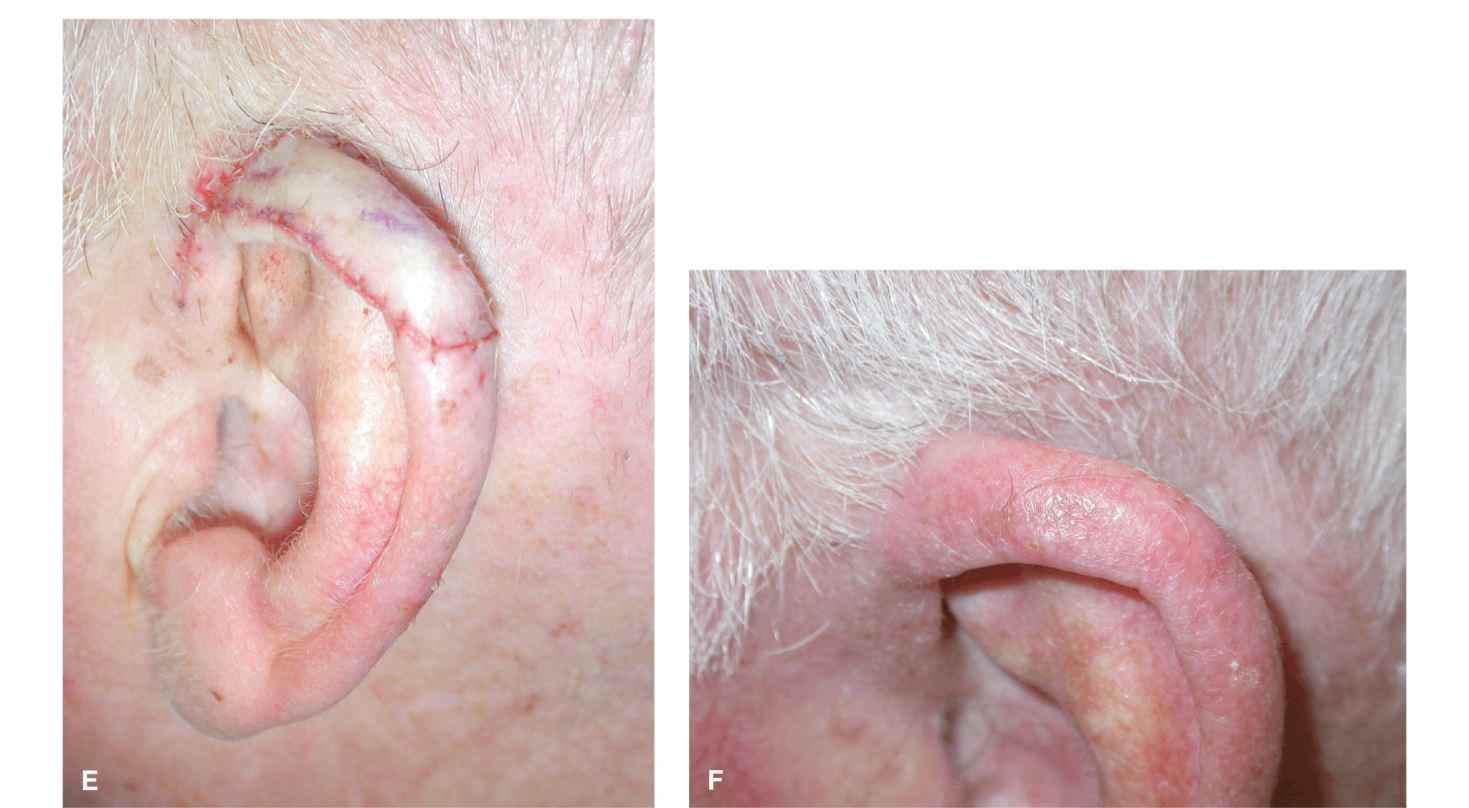

Helical Rim Advancement

Defects of the helix may be repaired through simple helical rim advancement, taking advantage of the reservoir of tissue laxity of the lower helical rim and lobule. The ability to perform a helical rim advancement for a given size defect is variable. Some ears are long and have abundant mobile tissue to allow for the repair. In other cases, the ear is substantially foreshortened and may not have an adequate reservoir of tissue. The lobule of the ear and the posterior pinna supply the tissue to be mobilized to repair the helical wound. The design of the helical rim advancement involves a long, sweeping incision along the anterior surface of the ear from the defect down to and into the lobule where it meets the antitragus (Figs. 8.7 and 8.8). Most often, the repair is composed of skin and soft tissue only. Incision is carried out to the anterior perichondrium, and the flap is then undermined over helical rim at this level and then dissected free of the posterior pinna. With the postauricular skin and subcutaneous tissue as a rich pedicle, this is a reliable reconstruction.5,6 A standing tissue cone is removed superiorly on the posterior surface of the ear as the flap advances and rotates into place.

Figure 8.7 Schematic of helical rim advancement. (A) A typical helical rim advancement flap. An incision is created along the anterior surface of the ear and carried into the lobule where a medial standing tissue cone is removed. The tissue is reflected off of the cartilage and maintained on a posterior pedicle. The flap is advanced, and the helical rim is approximated with eversion. A standing tissue cone is removed on the posterior surface of the ear. (B) A chondrocutaneous advancement flap. Incision is carried out through cartilage and the flap is advanced and rotated into place. The inclusion of cartilage may be of greater benefit when the defect is higher on the helix or when more cartilage has been lost in the operative wound

Figure 8.8 Clinical examples of helical rim advancement flaps. (A1-A3) A modest sized wound is repaired. The advancement is elevated above the perichondrium and cartilage is not included in the flap. (B1-B3) A small wound is repaired with a helical rim advancement. A dog-ear has been removed into the lobule at the inferior aspect of the antitragus. The healed repair is shown at 1 year. (C1-C3) A small wound is repaired with a small advancement. The edges are everted to closure to avoid the creation of a notch in the helix. The final result is at 1 year. (D1-D4) A larger wound is repaired with a helical rim advancement. The flap is widely undermined from the posterior perichondrium to allow for freedom of motion. There is a substantial element of rotation to the helical rim advancement. A Z-plasty has been utilized to assist in maintaining the lobule. The repair is shown immediately and at 3-month follow-up

The undermining plane for the helical rim advancement is over perichondrium. In most cases, extensive undermining of the posterior surface of the ear is required, and strict hemostasis is essential, as a large dead space will be created. As the flap advances (and rotates) into place, it is often helpful to create a bevelantibevel closure along the helical rim juncture. This or a small Z-plasty can avoid a notch In the ear where the tension is greatest and the opposing defect margins meet. When the defect is higher on the ear, the anterior incision is often extended through the cartilage to the opposing perichondrium. This creates a chondrocutaneous advancement.7–9 When the defect is relatively large and the ear moderate to small in size, it may be necessary to excise a crescent of cartilage within the scapha in order to avoid buckling of the ear.

The helical rim advancement flap with an intact postauricular pedicle is richly vascularized. Given the dead space created on the postauricular surface of the flap and the tendency of the flap tension to tent the space from the helix to the postauricular sulcus, it can be useful to place several tacking sutures through the ear to the anterior surface, thus ablating the dead space. When performing a flap where undermining extends to the postauricular sulcus, it is important not to traumatize the greater auricular nerve.

Although the star-shaped wedge ear reconstruction often cups the ear anteriorly, the helical rim advancement often flattens the natural convexity of the helix, especially when it is done as a chondrocutaneous flap.10 This is less problematic in most cases but should be discussed with the patient before closure. The other drawback to the helical rim advantage is the frequent mismatch between the thickness, curvature, and reflection of the upper helix and the flatter, less developed lower helix. This may create a step off deformity similar to when the lateral vermillion of the lip is advanced medially and meets the broader medial vermillion.

While the most common helical rim advancement is inferiorly based, the proximal helix can be advanced and rotated to repair defects closer to the root of the helix (Fig. 8.9).11 In such cases, the flap undergoes more of a rotational motion, and its movement is enhanced by a backcut on the root of the helix.

Figure 8.9 A proximal rim defect is repaired by rotating the proximal helix with a backcut. (A) The flap is designed and is based posteriorly. (B) The arc of rotation is along the helix. (C) The flap is incised and elevated at the perichondrium. (D) Redraping over the operative wound under little to no tension. (E) Repair at suturing. (F) Six-month final result

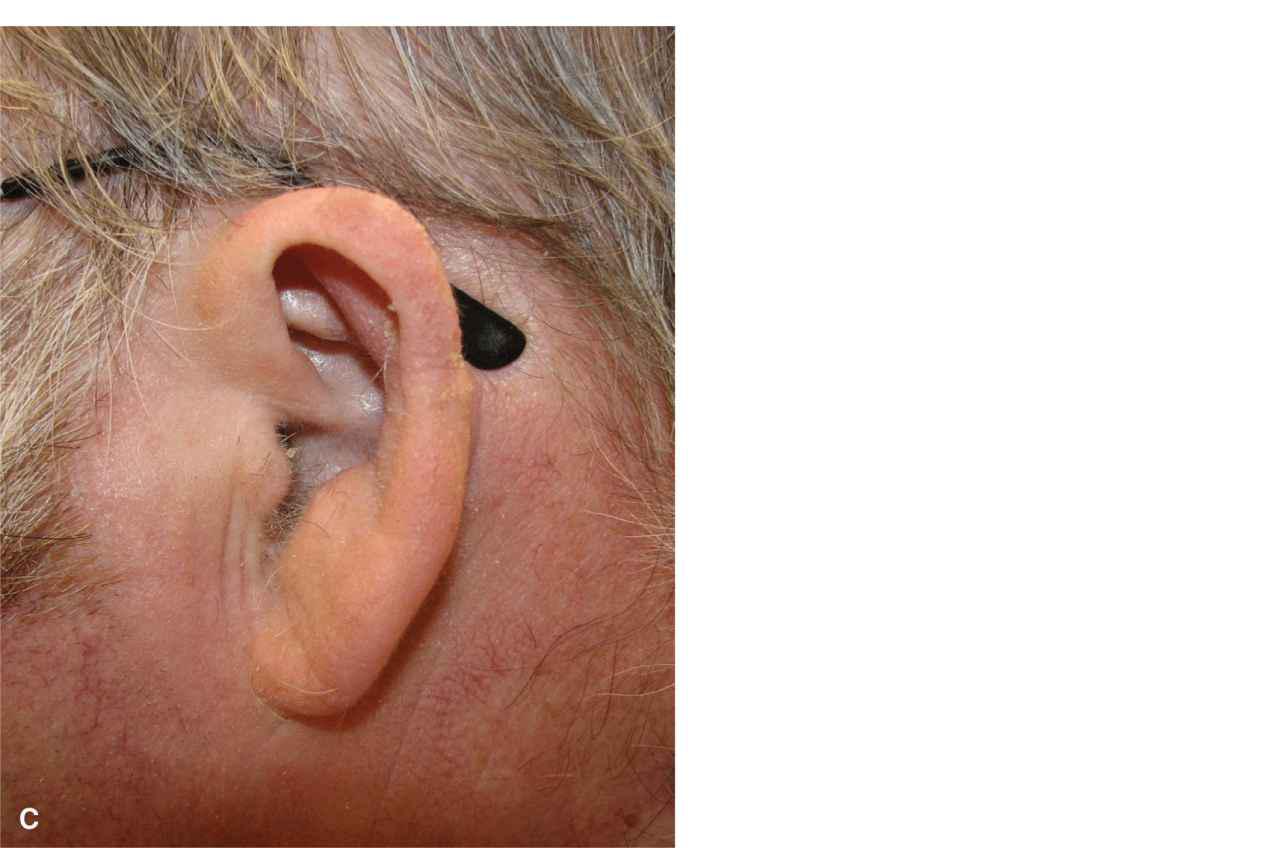

Banner Transposition Flaps

Defects of the upper helical rim are often beautifully repaired with postauricular banner flap (Fig. 8.10)12,13 and defects of the root of the helix can be repaired with either preauricular or postauricular banner flaps. The flaps are elevated above fascia and have a predictable vascular supply from the superior auricular branch of the superficial temporal artery and/or from the superior extensions of the postauricular artery. Such flaps will easily survive with length-to-width ratios of 4:1 or even 5:1 as long as they are transposed under minimal tension and without torsion of the pedicle. All tension can be directed along the closure of the secondary defect either in the postauricular sulcus or in front of the ear. If a banner flap is not likely to provide adequate motion, a bilobed transposition flap can be designed with its primary lobe on the posterior surface of the pinna and its secondary lobe in the postauricular sulcus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree