Double-Z Rhomboid Plasty for Reconstruction of Facial Wounds

F. N. GAHHOS

EDITORIAL COMMENT

This is a good alternative procedure, particularly for defects in which there is no mobility for correction with a single rhomboid flap. The use of two flaps gives a more satisfactory result without creating secondary deformities.

The double-Z rhomboid plasty, a technique of four transposition pedicle flaps, is characterized by borrowing the required tissue from two nonadjacent, opposite sides of the defect (1). When used in the face, where primary closure or reconstruction with direct tissue advancement is not feasible, the technique will avoid displacement or distortion of mobile anatomic landmarks (2). The flaps can be developed as strictly cutaneous, fasciocutaneous, or myocutaneous.

INDICATIONS

There are four main indications for the use of the double-Z rhomboid plasty in the face and neck: (a) when there is tissue availability in only two opposite directions, where closure by advancement flaps is not possible; (b) for prevention of the displacement of tissue landmarks such as lips, eyebrows, and nose; (c) for reconstruction of defects of two different tissue types, such as skin and mucosa or skin and hair-bearing skin; and (d) in the presence of wrinkles, to support the requirements of placing most scars in that direction. Proper orientation, planning, and rotation of the flap axis and placement of mobile landmarks along relaxed skin tension lines, as well as minimizing the need for advancement of the transposed flaps, will provide excellent cosmetic results.

ANATOMY

The double-Z rhomboid plasty is a technique involving multiple transposition pedicle flaps. The underlying muscle fascia or muscle can be incorporated into the flaps in areas of compromised circulation. As with other cutaneous flaps in the face, the axial skin blood supply can be disregarded. The design is simple, and the orientation is based on relaxed skin tension lines.

FLAP DESIGN AND DIMENSIONS

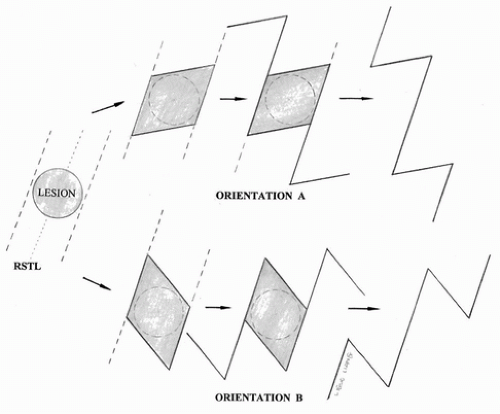

The first consideration in design is the optimal orientation of the rhombus containing the lesion, which is marked along with an appropriate margin of normal skin. A standard rhombic defect has a long and short axis; the double-Z rhomboid

plasty borrows from each side of the long axis. Determining the optimal orientation is perhaps the most difficult aspect, and adequate time should be taken to design the flaps correctly. The relaxed skin tension line is determined, which can be done by pinching the skin between the thumb and index finger in the area of the lesion to determine the direction of maximum tissue availability. Two lines are drawn along the edges of the planned skin defect, which must be parallel to the relaxed skin tension lines (Fig. 102.1). There are two possible orientations that will result in both minimal closure tension and maximal cosmesis. The surgeon will choose the design that least distorts adjacent anatomic landmarks.

plasty borrows from each side of the long axis. Determining the optimal orientation is perhaps the most difficult aspect, and adequate time should be taken to design the flaps correctly. The relaxed skin tension line is determined, which can be done by pinching the skin between the thumb and index finger in the area of the lesion to determine the direction of maximum tissue availability. Two lines are drawn along the edges of the planned skin defect, which must be parallel to the relaxed skin tension lines (Fig. 102.1). There are two possible orientations that will result in both minimal closure tension and maximal cosmesis. The surgeon will choose the design that least distorts adjacent anatomic landmarks.

The desired direction of the final incisions may also aid in the choice of orientation. Regardless of the orientation used, the major incision and two of the minor incisions will end up parallel to the relaxed skin tension lines and to each other. The remaining two incisions will vary in direction, depending on the chosen rhombic orientation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree