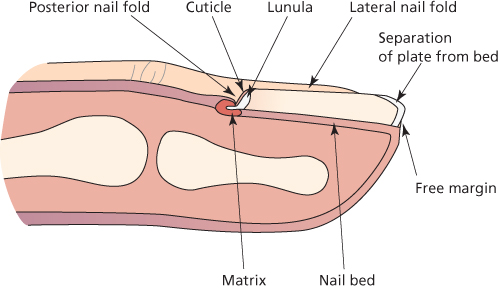

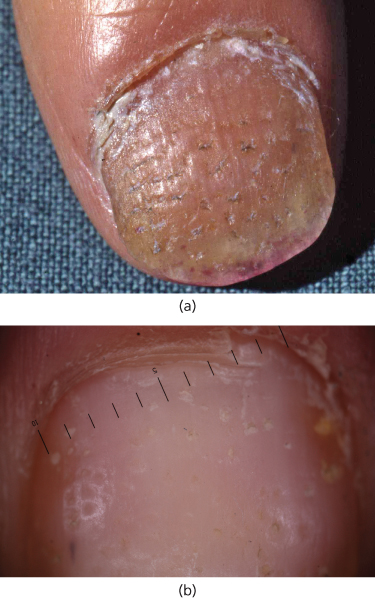

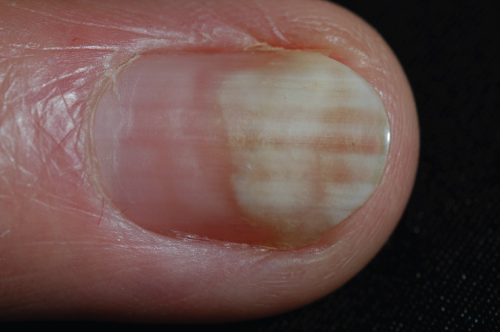

Chapter 20 In humans, the main function of the nails is to protect the distal soft tissues of the fingers and toes from the physical trauma of everyday life. The nail is derived from the ectoderm and is composed of keratin (Figure 20.1). The nail plate grows forward from a fold of epidermis over the nail bed, which is continuous with the matrix proximally. Nail keratin is derived mainly from the matrix with contributions from the dorsal surface of the nail fold and the nail bed. Figure 20.1 Section through finger. The nail grows slowly for the first day after birth and then more rapidly until it slows in old age. The rate of nail growth is greater in the fingers than the toes, particularly on the dominant hand. It is slower in women but increases during pregnancy. Finger nails grow at approximately 0.8 mm per week and toe nails 0.25 mm per week. This is seen clinically as small surface depressions of the nail plate that result from a loss of the parakeratotic scale such as occurs in psoriasis (Figure 20.2a and b showing nail pitting and appearances with a dermatoscope). The scale develops through inflammatory diseases affecting the proximal nail matrix including psoriasis, eczema, lichen planus and alopecia areata. Figure 20.2 (a) Pitting of nail and (b) pitting of nail appearance with dermatoscope. Where scaling occurs beneath the nail in the distal nail bed, the compacted scales build up to produce dense subungual hyperkeratosis. This is most commonly seen in psoriasis, eczema and fungal nail disease. In the toes, it may be part of a reaction to trauma or generalised hyperkeratosis. This sign is specific to psoriasis and reflects the presence of a patch of psoriasis in the nail bed with no connection to the free edge. There is discolouration of the nail, giving an oily appearance. Nail plate attachment to the nail bed may be lost by various degrees. This can be due to an inflammatory, traumatic or infective process affecting the distal nail bed, altering its biological function allowing nail plate attachment. Acute trauma usually settles with re-adherence. Forms of chronic trauma include manicure where the person uses a sharp instrument to remove subungual debris from beneath the nail (Figure 20.3). This form of trauma may be a sole cause of onycholysis, or may be a factor in association with a skin disease, such as psoriasis. Systemic causes of onycholysis include thyrotoxicosis. Figure 20.3 Onycholysis due to manicure beneath the nail. Chronic onycholysis becomes vulnerable to secondary infection with microbes that thrive in warm damp spaces. These are mainly Candida spp. and Pseudomonas pyocyanae. Such microbes may contribute to the persistence of the split from the nail bed and will increase discomfort and malodour. The nail plate thickens and becomes yellow in a wide range of diseases and also as part of normal ageing on the toes. Eczema, psoriasis, lichen planus and yellow nail syndrome are the main inflammatory diseases with this effect. Fungal infection can result in the same problem, although as in all the inflammatory diseases it may be possible to make a distinction between thickening due to increase of subungual keratin and thickening due to change in the nail plate (Figure 20.4). Chronic trauma can cause thickening, where the response of the nail is analogous to that of the skin in general. This is seen in hammer toe, where the free edge of the toe is directed downwards to act like a piano string hammer at each step. This force transmits back to the nail matrix and results in thickening of the nail. Figure 20.4 Onycholysis and hyperkeratosis of nail plate in psoriasis. These are most commonly seen in psoriasis and eczema where there is inflammation of the proximal nail fold and secondary change of nail matrix function. Isolated digital trauma may cause a similar, but solitary, transverse ridge. This is a significant cause of chronic paronychia. Common factors are a low threshold for an irritant reaction, such as background atopy or skin problems elsewhere, in combination with an occupational irritation of the skin at the base or sides of the nail. This resulting inflammation spreads to involve the nail matrix. When further combined with damp or wet work (which is a common form of irritant) there is a disposition to secondary infection with Candida spp. A substantial general physiological disturbance can result in a solitary episode of reduced nail matrix function. If this reduction falls short of complete matrix shut down, then there is a partial thickness transverse break in the nail plate. This will normally affect many nails at once, with subsequent nail growth marking out the time of recent disturbance such as a date in a calendar record of the preceding months. This was originally identified by Joseph Beau, a Parisian cardiologist who termed it retrospective semeiology, from the Greek, meaning to study signs and symbols. While it is most commonly thought to be an indicator of past physiological changes, it is also seen in people who have a severe deterioration in their eczema or psoriasis as well as less common diseases, such as bullous pemphigoid. Where the nail matrix inflammation is global and severe, it may be sufficient to precipitate nail shedding and interruption of nail matrix nail plate production entirely. This can be a result of severe inflammatory skin disease or an episode of trauma. The latter is particularly the case when there is substantial bleeding beneath the nail, which separates the nail from the nail bed. A single split on one nail with no other nail or skin disease is most likely to represent an area of focal matrix damage (Figure 20.5). This can be due to acute trauma with scarring, chronic trauma from underlying or overlying mass or a dysplastic process destroying a small area of nail matrix such that it does not produce nail. Such presentations need close examination and imaging and may require surgical exploration and sampling. Where longitudinal splits are multiple, they are usually a result of a generalised inflammatory or degenerative process. The most typical of these are lichen planus and ageing, respectively. Ageing is a non-specific process, where there is a loss of nail substance and increased fragility, giving rise to splits. These are usually only manifested in the distal few millimetres of nail. A hybrid between inflammation and degeneration is seen in the genodermatosis Darier’s disease where distal nicks in the nail may extend proximally to be markedly destructive (Figure 20.6). This is usually seen in combination with other signs specific to this disease. Figure 20.5 Longitudinal ridge and partial split termed canaliform dystrophy of Heller. Matrix inflammation with nail fold trauma can play a part. Figure 20.6 Darier’s disease. This is seen in childhood mainly in the big toes and where there is thumb sucking. It can also be seen in middle age and beyond, probably as part of a degenerative process. It represents a loss of adherence between the lamellae of the nail plate, which is made up of a tier of over 100 cells in the vertical axis. As the nail reaches the free edge, it is vulnerable to the action of solvents penetrating the free edge and promoting loss of cohesion between the lamellae. This is more strictly a periungual sign, but with significance to the nail. Pustules can be sterile or reflect infection. In the acute presentation, it is always wise to assume infection until proven otherwise. Infective causes are typically through minor trauma and pyogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus where the red and swollen digit will also have one or more pustules. This is an acute paronychia. Herpes simplex can produce a similar appearance although the pustules are smaller, more numerous and clustered and have a vesicular character. Candida can also result in pus, but usually with a more indolent course. Sterile pustules are usually due to psoriasis. There may be less pain and associated inflammation than with the acute infective disease and multiple digits might be involved as well as other body sites. The pustules gradually resolve, leaving a brown residue. In some instances, sterile psoriatic pustules can affect the nail unit either as part of more generalised pustular psoriasis or as variants of palmoplantar pustulosis or acrodermatitis or Hallopeau.

Diseases of the Nails

OVERVIEW

Introduction

Changes of shape and attachment

Pitting

Subungual hyperkeratosis

Oily spot

Onycholysis

Nail plate thickening

Transverse ridges

Irritant dermatitis (eczema)

Beau’s line

Nail loss (onychomadesis)

Longitudinal splits

Transverse (lamellar) splits

Pustules in the periungual skin

Koilonychia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree