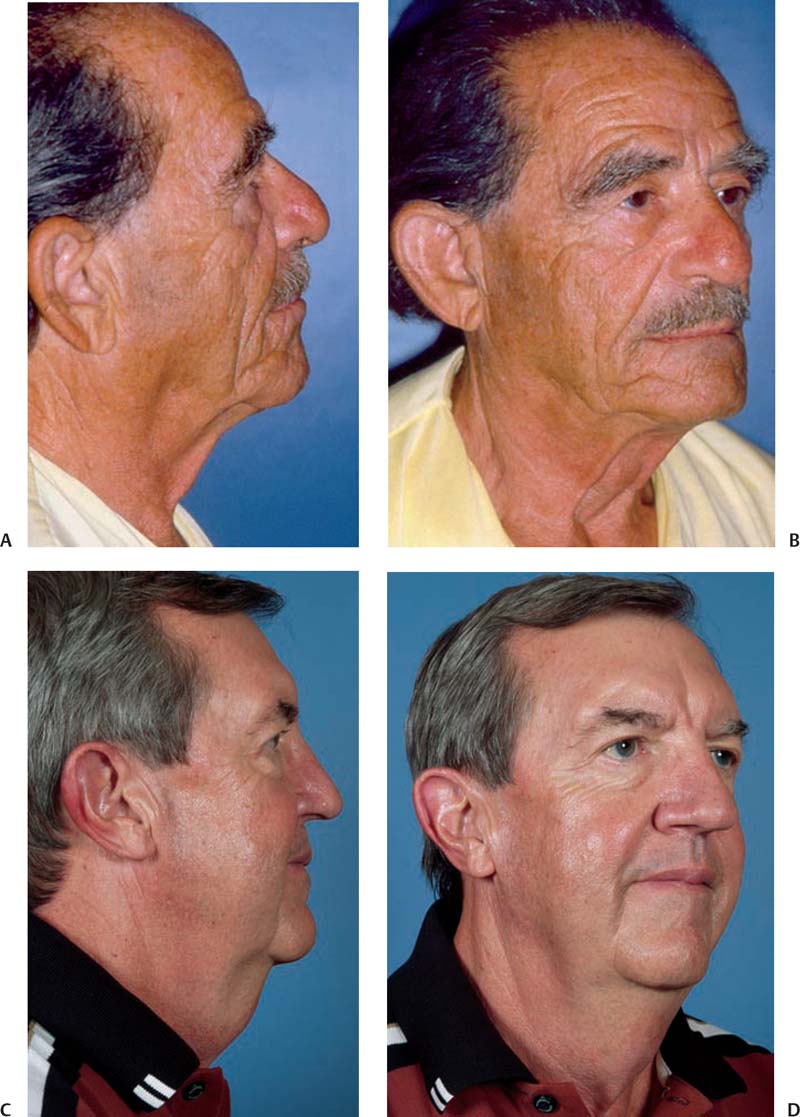

9 Direct-excision techniques for managing the neck have a long history in cosmetic rejuvenation surgery. They offer an alternative or adjunct to facelifting, liposuction, and platysmal imbrication. Their usefulness is manifold and they provide an alternative to more aggressive approaches to rejuve-nation of the face. Direct excision is appropriate for patients with isolated cervical laxity, medical conditions contraindicating more prolonged procedures that may require deeper anesthesia, and isolated submental failure after rhytidectomy, as well as for the patient disinclined to undergo a facelift (Fig. 9.1). Moreover, direct-excision techniques can create a defined cervicomental angle (CMA) that is difficult to obtain with any other technique (Fig. 9.2). Proper patient selection and education are imperative for direct-excision surgery just as for all procedures to improve the neck. Such surgery can address fullness, laxity, and banding in the neck. However, it does not improve the jaw line and may even worsen the appearance of an undulating jaw line by creating a regional discrepancy between the rejuvenated neck and the face. For this and other reasons, direct-excision surgery must be applied appropriately. Simple linear excision,1–3 the lazy H,4 T-Z plasty,5 running W-plasty,6 and Grecian urn techniques7,8 have all been described as ways to approach the “turkey gobbler” neck or “wattle.” Each procedure has its benefits and drawbacks. The problem that needs to be addressed by plastic surgery of the neck may be laxity, fullness, or platysmal banding, alone or in combination, and is compounded by a fixed structure in the mandible superiorly and the visibility of the vertical segment of the surgical scar beneath the hyoid bone inferiorly. The mandibular margin at the chin prevents the smooth tapering of any linear vertical excision when immediate submental laxity, skin redundancy, is present. Moreover, with vertical excision, a standing cutaneous cone can be created at the menton. The segment of the vertical excision inferior to the CMA may be visible and must be camouflaged. The CMA is defined by the position of the chin, hyoid bone, degree of laxity of cervical skin, submental adiposity, and relaxation of the platysma muscle. Abnormalities in any of these factors can create an obtuse CMA. However, although such abnormalities can occur in isolation, they are most often seen in combination. With the exception of the position of the hyoid bone, the perception of all of these abnormalities can be addressed with direct excision. To achieve the goal of an improved CMA, reduced skin laxity, and refinement of the contour of the neck, the surgeon must define the pathology that requires correction and the best approach to accomplishing this. Submental laxity of skin and adiposity can extend superiorly to a level immediately adjacent to the menton, usually stopping at the submental crease, but sometimes extending inferiorly to the clavicles and manubrium. Some degree of sagittal excision of skin must therefore be done immediately adjacent to the mandible superiorly, and possibly also at the inferior extent of the excision at or below the position of the cricoid cartilage. With vertical linear extension of the incision for skin excision there will be a tendency to create a standing cutaneous cone or cones of midline skin at the superior, menton, and inferior, cricoid or thyroid cartilages, extent of the excision. This can only be avoided by incorporating an A-T closure or W-plasty at the submental crease, to keep the incision from crossing the mandibular margin at the menton. With the vertical elliptical excision of skin, the inferior limb of the transverse elliptical excision at the submental crease must be lengthened.6 This can be done by having the incision take the form of an arc half the length of the transverse submental incision. Doing this makes each side of the transverse submental excision of equal length, with the goal of avoiding bunching of skin upon closure of the incision, and it shortens the vertical dimension, length, of the ellipse of skin which is to be excised, with the goal of avoiding vertical banding in the neck. The vertical shortening of the transverse ellipse in the skin of the neck is resolved with the addition of tissue through the creation of transposition flaps in the form of a Z-plasty7 at the level of the hyoid bone. This both increases the extent of vertical soft tissue at the site of the excision and breaks the linearity of the incision following its closure, which helps to camouflage the incision scar. Fig. 9.1 Multiple pathologies can contribute to the submental wattle, all of which can be addressed with direct-excision techniques. (A) Excess skin and (B) platysmal banding. (C) Sub-mental adiposity and (D) excess skin. When the vertical elliptical excision of skin from the neck is given the respective stopping points of transverse elliptical excisions superiorly at the submental crease and inferiorly at sites of orthostatic rhytids in the neck, the shape of the area of surgery on the neck is that of a Grecian urn, with a Z-plasty at the desired level of the CMA. When the laxity of cervical skin is limited to the immediate submental area, as can occur after a facelift, and especially after a limited procedure, an A-T plasty or direct linear excision of excess skin can be appropriate, but the excision must remain above the CMA. No linear excision should cross the CMA because this carries the risk of contracture and webbing. Lengthening and release of the linear incision with a Z-plasty is done to avoid these risks (Fig. 9.3). The use of bilateral advancement flaps, as in the H excision, to correct the defect created by the excision of midline skin, will leave a combined length on the excisional side of the submental and inferior incisions that is less than the length of the incision on the non-excisional sides of the transverse incisions. Fig. 9.2 Presurgical marking for the position of the CMA. Fig. 9.3 A submental scar is usually visible only with extension of the neck. The transverse H or lazy H excision technique4 fails to address the problem created by the lengths of the transverse components of the incision in the submental area and inferiorly. This discrepancy will create a standing cutaneous cone in the superior and inferior distal skin.

Direct-Excision Techniques

Choosing a Technique for Direct Excision

Addressing the Problems Requiring Direct-Excision Surgery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree