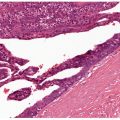

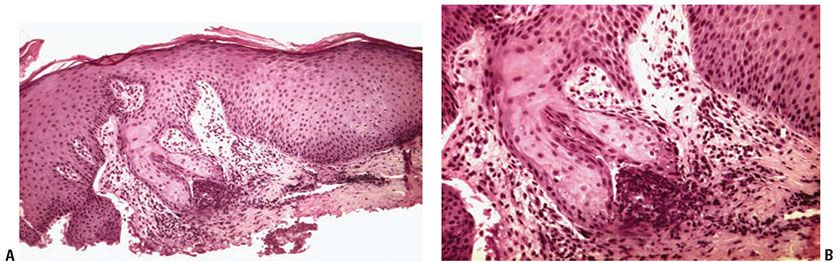

Figure 15-1 Solar (actinic) degeneration. A: In the upper dermis, separated from the epidermis by a narrow band of normal collagen, there are aggregates of thick, interwoven bands of the elastotic material. B: Extensive amorphous material can be seen around and among elastic and collagen fibers.

On staining with silver nitrate, the distribution of melanin in the basal cell layer may appear irregular, in that areas of hyperpigmentation alternate with areas of hypopigmentation (6).

Pathogenesis. Electron microscopic examination of areas of solar elastosis shows elastotic material as the main component (EM 13). Even though this elastotic material resembles elastic tissue in its chemical composition, it differs significantly in appearance from aged elastic fibers in unexposed, aged skin. Instead of showing amorphous electron-lucent elastin and aggregates of electron-dense microfibrils (Chapter 3), the thick fibers of elastotic material show two structural components: a fine granular matrix of medium electron density and, within this matrix, homogeneous, electron-dense, irregularly shaped inclusions (7). Microfibrils such as those observed in normal or aged elastic fibers are absent. Immunoelectron microscopy shows that the elastotic material has retained its antigenicity for elastin but not for microfibrils (8). The number and size of elastotic fibers are greatly increased over the number and size of elastic fibers found in normal or aged skin. Extensive amorphous material can be seen around the elastotic fibers and also among the collagen fibrils. Collagen fibrils are diminished in number, with those present often showing a diminished electron density, a diminished contrast in cross striation, and a splitting up into filaments at their ends (9).

Elastotic material is not regarded as a degeneration product of preexisting elastic fibers. Most current findings indicate that elastotic material is composed primarily of elastic tissue, much of which may be newly formed as the result of an altered function of fibroblasts. Evidence of transcriptional activation of the elastin gene in biopsied tissue and fibroblast cultures from sun-damaged skin further supports this. Additional accumulation of elastotic material may be secondary to a disruption in the balance between synthesis and degradation of elastin in photodamaged skin (10).

The elastotic material that histochemically stains like elastic tissue resembles elastic tissue in its chemical composition and its physical and enzymatic reactions. Thus, the amino acid composition of the elastotic tissue resembles that of elastin and differs significantly from that of collagen. In particular, the elastotic material, like elastic tissue, has a much lower content of hydroxyproline than collagen (11). Moreover, the elastotic material in unfixed sections shows the same brilliant autofluorescence as do elastic fibers on examination with the fluorescence microscope (12), and both the elastotic material and elastic tissue are susceptible to elastase digestion (13). The elastotic material contains a large amount of acid mucopolysaccharides, as indicated by staining with alcian blue. A significant portion of these acid mucopolysaccharides may be sulfated because prior incubation with hyaluronidase removes only 50% to 75% of the alcian blue-positive staining. The basophilia of the elastotic material, however, is not affected by incubation with hyaluronidase (14).

The irregular distribution of melanin in the epidermis observed in some patients with solar degeneration, when studied by electron microscopy, is found to be caused largely by an impairment of pigment transfer from melanocytes to keratinocytes. Although some keratinocytes contain many melanosomes, others contain few or no melanosomes. The latter are surrounded by dendrites laden with melanosomes (15).

Differential Diagnosis. For a discussion of differentiation of solar elastosis from pseudoxanthoma elasticum, see Chapter 3.

Principles of Management. Consistent, long-term use of sunscreens and/or photoprotective clothing reduces solar elastosis significantly (16). Dermabrasion and long-term application of retinoic acid can lead to thickening of the epidermis, which may reduce the clinical appearance of photoaging (17,18). On certain sites, select lasers may ameliorate some of the accumulated photodamage as well.

LOCALIZED EXPRESSIONS OF SOLAR ELASTOSIS

Several clinically distinct forms of localized solar elastosis have been described. In the nuchal region, the skin, after many years of exposure to the sun, may appear thickened and furrowed. This is referred to as cutis rhomboidalis nuchae. Elastotic nodules of the ears are localized papular and nodular forms of solar elastosis usually occurring on the antihelix (19–22). Severe solar elastosis may also occur as yellowish plaques associated with small cysts and comedones. Favre–Racouchot syndrome (nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones) is an example occurring on facial skin lateral to the eyes (23,24). A similar condition occurring on the arms has been termed actinic comedonal plaques (25–27). Two other types of circumscribed solar elastosis occurring on the upper extremities are solar elastotic bands of the forearm (5,28) and collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (29–36).

Elastotic Nodules of the Ears

Clinical Summary. Elastotic nodules are most often bilateral, small, asymptomatic, pale papules and nodules on the anterior crus of the antihelix and, occasionally, helix (21) of the ears (19,20,22).

Histopathology. Irregular elastotic fibers and clumps of elastotic material are seen in the background of marked dermal solar elastosis (Fig. 15-2A). The fibers and clumps can be highlighted with a Verhoeff-van Gieson elastic stain (Fig. 15-2B) (21).

Figure 15-2 Elastotic nodule of the ear. A: A dome-shaped papule with marked solar elastosis in the dermis and clumped and irregular eosinophilic material representing degenerated elastic fibers. B: The course, clumped material is highlighted with an elastic stain.

Differential Diagnosis. Clinically, they may mimic basal cell carcinomas, amyloidosis, gouty tophi, or chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis (19–22).

Favre–Racouchot Syndrome (Nodular Elastosis with Cysts and Comedones)

Clinical Summary. Favre–Racouchot syndrome is characterized by yellow plaques with multiple open and cystically dilated comedones. The condition typically affects the skin lateral to the eyes in elderly males (23,24,37). However, a case has also been documented on the shoulder (38). Although the condition is usually bilateral, it may be unilateral (39–41).

Histopathology. Dilated pilosebaceous openings and large, round, cystlike spaces are lined by a flattened epithelium and represent greatly distended hair follicles (23,24). Both the dilated pilosebaceous openings and the cystlike spaces are filled with layered horny material. Vellus hair shafts and bacteria have been demonstrated within the spaces as well, suggesting the cystlike spaces may represent closed comedones rather than true infundibular cysts (42). The sebaceous glands are atrophic. Solar elastosis often is pronounced (23), but it may be slight or absent (43). Because the comedones are open, they do not tend to become inflamed (44) (see section on Acne Vulgaris, Chapter 18).

Pathogenesis. It is thought to be primarily secondary to prolonged solar exposure with the formation of comedones facilitated by an extracellular matrix of compromised structural integrity (2). Smoking may also be a contributing factor in its development (45).

Actinic Comedonal Plaques

Clinical Summary. In actinic comedonal plaques, solitary nodular plaques with a cribriform appearance and comedone-like structures occur, often unilaterally, on the arms or forearms (25–27). The plaques are composed of confluent erythematous to bluish papules and nodules. The condition has been described in fair-skinned individuals with a history of chronic sun exposure. They can be found in association with Favre–Racouchot syndrome and may, in fact, represent an ectopic expression of this entity (26).

Histopathology. Dilated corneocyte-filled follicular lumina are present within areas of elastotic, amorphous material. The overlying epidermis is usually dyskeratotic and atrophic. The histologic findings are quite similar to those seen in Favre–Racouchot syndrome (25,26).

Solar Elastotic Bands of the Forearm

Clinical Summary. Solar elastotic bands of the forearm consist of soft cordlike plaques across the flexor surface of the forearms (5,28). The bands occur in areas of actinic damage and usually with senile purpura.

Histopathology. Nodular collections of basophilic homogenous amorphous material underlying an atrophic epidermis are conspicuous features. Thickened degenerated elastic fibers within the homogenous material are also observed. Stellate fibroblasts and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are found in close apposition to the elastic fibers. The nodular collections and thickened elastic fibers stain positively with Verhoeff-van Gieson elastic stain (5).

Collagenous and Elastotic Marginal Plaques of the Hands

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands have been described by several names: elasto-collagenous plaques of the hands (29), degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands (30,32), and keratoelastoidosis marginalis (31).

Clinical Summary. This acquired, slowly progressive condition is usually seen in elderly males and consists of groups of linear confluent papules along the medial and lateral aspects of the hands at the juncture of the palmar and dorsal surfaces. The medial aspect of the thumb and radial aspect of the index finger are most commonly affected. The condition closely resembles the genodermatosis, acrokeratoelastoidosis (34). However, there is no familial predisposition or involvement of the plantar surfaces (31,46,47).

Histopathology. The reticular dermis displays an acellular zone of haphazardly arranged collagen with some bundles running perpendicular to the epidermis (32). The bundles of collagen are admixed with fragmented elastic fibers and distinctive angulated amorphous “basophilic elastotic masses” in the upper dermis. These masses can be demonstrated to contain degenerating elastic fibers and calcium (33).

Pathogenesis. Actinic damage and chronic repetitive pressure or trauma has been implicated in its pathogenesis (31,46,47).

PERFORATING DISORDERS

The perforating disorders comprise a group of disorders sharing the common characteristic of transepidermal elimination (TEE). This phenomenon is characterized by the elimination or extrusion of altered dermal substances and, in some cases, by such material behaving as foreign material.

Traditionally, four diseases have been included in this group: Kyrle disease (hyperkeratosis follicularis et parafollicularis in cutem penetrans), perforating folliculitis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), and reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC). A fifth entity, acquired perforating dermatosis (APD), which is usually associated with renal disease and/or diabetes mellitus, in which clinical and histologic findings may resemble any of these four diseases, has been added to this group (48). Although TEE is a prominent feature in all these conditions, it has also been described as a secondary phenomenon in other entities, including such inflammatory disorders as granuloma annulare, one variant of pseudoxanthoma elasticum, and chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. Elastic fibers can be transepidermally eliminated overlying sites of healing wounds. Collagen may be eliminated through keratoacanthomas (49). Needless to say, there is a long list of other conditions that can exhibit TEE as an associated reaction pattern.

Kyrle Disease

Kyrle disease is a rare disorder, described by Kyrle in 1916 (50). There is controversy as to whether it represents a distinct entity, an exaggerated form of perforating folliculitis (50,51), or whether it actually comprises a group of disorders with similar epidermal–dermal reaction patterns associated with chronic renal failure, diabetes, prurigo nodularis, and even keratosis pilaris. Therefore, the discussion of Kyrle disease and perforating disorders seen in chronic renal disease and/or diabetes has a very broad overlap in terms of their clinical and pathologic features.

Clinical Features. This eruption presents with a large number of papules, some coalescing into plaques, numbering in the hundreds and often distributed on the extremities. Although some may appear to involve the follicular units, these lesions are more likely to be extrafollicular. The typical patient is young to middle-aged and often has a history of diabetes mellitus. The papules are dome shaped, 2 to 8 mm in diameter, with a central keratotic plug. Excoriations often are found in the vicinity of these lesions. Linear lesions related to possible koebnerization have been described.

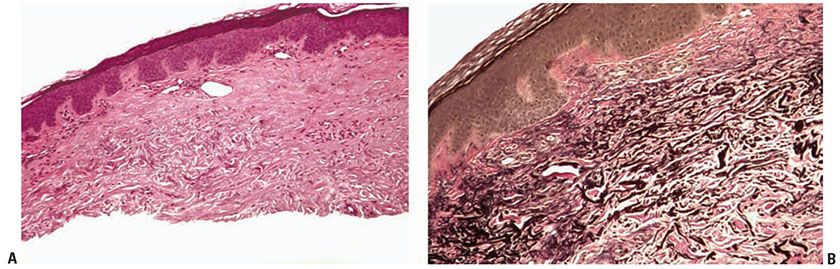

Histopathology. The essential histopathologic findings include (a) a follicular or extrafollicular cornified plug with focal parakeratosis embedded in an epidermal invagination, (b) basophilic degenerated material identified in small collections throughout the plug, with absence of demonstrable collagen and elastin, (c) abnormal vacuolated and/or dyskeratotic keratinization of the epithelial cells extending to the basal cell zone, (d) irregular epithelial hyperplasia, and (e) an inflammatory component that is typically granulomatous with small foci of suppuration (Fig. 15-3). In most instances, it is important to perform elastic tissue stains and even trichrome stains to exclude perforating elastic fibers, as in EPS, or collagen fibers, as in RPC (52).

Figure 15-3 Kyrle disease. A large parakeratotic plug containing basophilic debris lies within an invagination of the epidermis. The underlying dermis displays acute and chronic inflammation.

Pathogenesis. The primary event is claimed to be a disturbance of epidermal keratinization characterized by the formation of dyskeratotic foci and acceleration of the process of keratinization. This leads to the formation of keratotic plugs with areas of parakeratosis (53–55). Because the rapid rate of differentiation and keratinization exceeds the rate of cell proliferation, the parakeratotic column gradually extends deeper into the abnormal epidermis, leading in most cases to perforation of the parakeratotic column into the dermis. Perforation is not the cause of Kyrle disease, as originally thought (50), but rather represents the consequence or final event of the abnormally sped-up keratinization. This rapid production of abnormal keratin forms a plug which acts as a foreign body, penetrating the epidermis and inciting a granulomatous inflammatory reaction. A certain similarity exists between the parakeratotic column in Kyrle disease and that observed in porokeratosis of Mibelli (54). In both conditions, a parakeratotic column forms as the result of rapid and faulty keratinization of dyskeratotic cells, but, whereas in Kyrle disease the dyskeratotic cells are often used up so that disruption of the epithelium occurs, the clone of dyskeratotic cells can maintain itself in porokeratosis of Mibelli by extending peripherally.

Differential Diagnosis. See Table 15-1.

Principles of Management. Patients may experience reduced pruritus and decreased lesion symptomatology with regular renal-replacement therapy when the condition occurs in the setting of end-stage renal disease. Other treatment modalities are generally supported by case reports and anecdotal evidence, but may include topical anti-inflammatory or antipruritic agents, including topical corticosteroids, or, in some cases, topical retinoids. Limited lesions may respond to local destructive methods, including cryotherapy.

Perforating Folliculitis

Perforating folliculitis is a perforating disorder that has many features overlapping with Kyrle disease and also comprises one of the clinical and histologic patterns seen in APD.

Clinical Summary. As described by Mehregan and Coskey (56), this is a relatively uncommon disorder usually observed in the second to fourth decades and is characterized by erythematous follicular papules with central keratotic plugs. The lesions are 2 to 8 mm in diameter and tend to be localized to the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the buttocks. The key to making this diagnosis is the clinical and histologic identification of a follicular unit as the primary site for the inflammatory process.

Histopathology. The main pathologic abnormalities consist of (a) a dilated follicular infundibulum filled with compact ortho- and parakeratotic cornified cells (Fig. 15-4A); (b) degenerated basophilic staining material, composed of granular nuclear debris from nuclear neutrophils, other inflammatory cells, and degenerated collagen bundles (Fig. 15-4B); (c) one or more perforations through the follicular epithelium; and (d) an associated perifollicular inflammatory cell infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils. Additionally, altered collagen and refractile eosinophilically altered elastic fibers are found adjacent to the sites of perforation. When serial sections through the specimen are examined, a remnant of the hair shaft can sometimes be found.

Figure 15-4 Perforating folliculitis. A: A widely dilated follicular unit contains a mixture of keratin, basophilic debris, inflammatory cells, and degenerated collagen fibers. B: An area of disrupted follicular epithelium with adjacent associated perifollicular inflammation and alteration of collagen and elastic fibers.

Pathogenesis. Perforating folliculitis is the end result of abnormal follicular keratinization most likely caused by irritation, either chemical or physical, and even chronic rubbing. A portion of a curled-up hair is often seen close to or within the area of perforation or even in the dermis, surrounded by a foreign-body granuloma (55).

Differential Diagnosis. In Kyrle disease, the keratinous plug may be extrafollicular, the perforation usually is present deep in the invagination at the bottom of the keratinous plug, and no eosinophilic degeneration of elastic fibers is found. In addition, in Kyrle disease, epithelial hyperplasia is a significant feature. For a discussion of the differential diagnosis of perforating folliculitis from EPS, see the following section on Differential Diagnosis for Elastosis Perforans Serpiginosa. See also Table 15-1.

Principles of Management. Treatment of this condition is similar to that of Kyrle disease, discussed above.

Elastosis Perforans Serpiginosa

EPS is the most distinctive of the perforating disorders because it demonstrates the best example of TEE. In EPS, increased numbers of thickened elastic fibers are present in the upper dermis and altered elastic fibers are extruded through the epidermis.

Clinical Summary. EPS is a rare disorder that affects young individuals with a peak incidence in the second decade. Men are affected more often than women. It is primarily a papular eruption localized to one anatomic site and most commonly affecting the nape of the neck, the face, or the upper extremities. The papules are typically 2 to 5 mm in diameter. These papules are arranged in arcuate or serpiginous groups and may coalesce; there is often mild perilesional inflammation and erythema.

Of particular importance is the association of EPS with systemic diseases. These associations include Down syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, and Marfan syndrome. In addition, on rare occasions EPS is observed in association with Rothmund–Thompson syndrome or other connective tissue disorders, and as a secondary complication of penicillamine administration.

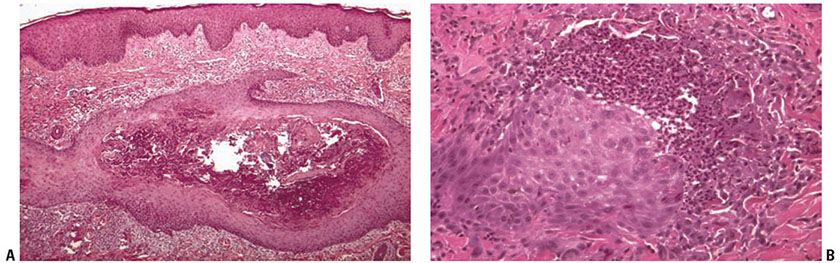

Histopathology. The essential findings include a narrow transepidermal channel that may be straight, wavy, or of corkscrew shape, and thick, coarse elastic fibers in the channel admixed with granular basophilic staining debris (Fig. 15-5A, B). A mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate accompanies the fibers in the channel. Also observed are abnormal elastic fibers in the upper dermis in the vicinity of the channel. In this zone the elastic fibers are increased in size and number. As these fibers enter the lower portion of the channel, they maintain their normal staining characteristics, but as they approach the epidermal surface they may not stain as expected with elastic stains (57).

Figure 15-5 Elastosis perforans serpiginosa. A: A portion of a narrow curved channel through an acanthotic epidermis is shown. B: The lower portion of the channel contains coarse elastic fibers and basophilic debris.

Pathogenesis. The cause of EPS is not known. Because the elastic fibers show no obvious abnormality within the dermis except hyperplasia, it is conceivable that the thickened elastic fibers act as mechanical irritants or “foreign bodies” and provoke an epidermal response in the form of hyperplasia. The epidermis then envelops the irritating material and eliminates it through transepidermal channels. The degeneration of the elastic fibers within the channels probably is caused by proteolytic enzymes set free by degenerating inflammatory cells (57). The channel is formed as a reactive phenomenon through which the “foreign bodies” are extruded. Because copper metabolism is essential to the formation of elastin (58) and because the administration of penicillamine, a copper chelating agent, has been found to induce EPS (59), it may be suggested that the primary abnormality begins with a defect in the metabolism of this essential element.

Differential Diagnosis (Table 15-1). Both Kyrle disease and perforating folliculitis have in common with EPS a central keratotic plug and a perforation through which degenerated material is eliminated. In addition, perforating folliculitis, like EPS, shows the elimination of degenerated eosinophilic elastic fibers. However, neither of the two diseases shows the great increase in elastic tissue that is observed in EPS in the uppermost dermis and particularly in the dermal papillae on staining with elastic tissue stains.

Principles of Management. Treatment modalities include local destruction with cryotherapy (60), topical medications including retinoids, corticosteroids, or salicylic acid, with rare reports of imiquimod (61) benefiting select patients. Systemic treatment can include retinoids (62). Other locally destructive methods may be considered in select cases.

Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

RPC is a rare perforating disorder in which altered collagen is extruded by means of TEE. True, classic RPC is a genodermatosis that is inherited as an autosomal dominant or recessive trait (63,64). The lesions are precipitated by trauma, arthropod assaults, folliculitis, and even exposure to cold. RPC occurs early in life, and both genders are equally affected. An adult, acquired type of RPC has been described in association with diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure (65–67) and may be best interpreted as an expression of APD (see text following).

Clinical Summary. The primary clinical lesion is a small papule that enlarges to the size of 5 to 10 mm with a hyperkeratotic central umbilication. Often the lesion appears eroded. These lesions spontaneously regress, leaving superficial scars with postinflammatory pigmentary alteration. Koebnerization is common.

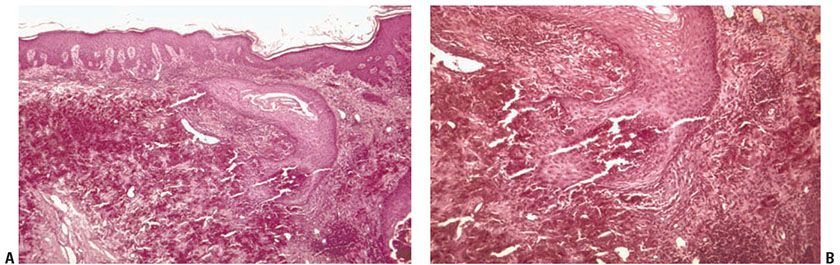

Histopathology. The classic lesion shows a vertically-oriented, shallow, cup-shaped invagination of the epidermis, forming a short channel (Fig. 15-6A). The channel is lined by acanthotic epithelium along the sides. At the base of the invagination there is an attenuated layer of keratinocytes that in some foci appear eroded. Within the channel there is densely packed degenerated basophilic staining material and basophilically altered collagen bundles. Vertically-oriented perforating bundles of collagen are present interposed between the keratinocytes of the attenuated bases of the invagination (Fig. 15-6B). It is important that a Masson-trichrome stain be done to confirm that the fibers are collagen.

Figure 15-6 Reactive perforating collagenosis. A: A shallow cup-shaped invagination of the dermis containing a mixture of basophilic material and degenerated collagen bundles. The adjacent epidermis displays acanthosis. B: Vertically-oriented perforating bundles of collagen are present at the base of the invagination.

Pathogenesis. The basic process in RPC consists of the TEE of histochemically altered collagen. Nevertheless, as delineated by electron microscopy, the collagen fibrils appear intact, with regular periodicity (68).

Differential Diagnosis. See Table 15-1.

Principles of Management. Topical retinoic acid and narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy have been successfully used to treat familial cases (69). See also the following Principles of Management section for APD.

Acquired Perforating Dermatosis

This term was suggested by Rapini et al. (48) to describe a pathologic process encompassing the various forms of TEE seen in patients with renal disease and/or diabetes mellitus. Differences in clinical and histologic features, such as the presence of koebnerization, or histologic evidence of follicular involvement with or without collagen fibers in the epidermis have variably led to diagnoses of Kyrle disease, “acquired” RPC, or perforating folliculitis. Other terms that have been used include perforating disorder secondary to chronic renal failure and/or diabetes mellitus, perforating folliculitis of hemodialysis, Kyrlelike lesions, and uremic follicular hyperkeratosis (70-72).

Clinical Summary. Lesions are frequently pruritic, and range from hyperkeratotic papules and nodules resembling Kyrle disease to RPC-like umbilicated papules, nodules, and plaques to erythematous, follicular papules and nodules mimicking perforating folliculitis (48,49,72). Annular plaques and erythematous pustules have also been described, with histologic features of RPC and perforating folliculitis, respectively (72). The most common location is the extensor surfaces of the extremities, especially lower, but the trunk and head can also be involved (48,72). APD has also been described in renal disease secondary to chronic nephritis, obstructive uropathy, anuria, and hypertension-related nephrosclerosis (49). Cases of APD have also been reported in patients with lymphoma, AIDS, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, and associated with pruritis secondary to liver disease, neurodermatitis, “atopic dermatitis” and malignant neoplasia (48,73).

Histopathology. As mentioned, the histologic features of APD are variable, even within different lesions from the same patient. When vertically-oriented, Masson-trichrome positive collagen bundles are present within a perforation, the findings are suggestive of RPC. When perforation is associated with a follicle, the findings resemble perforating folliculitis. However, chronic rubbing can lead to superimposed features of prurigo nodularis, distorting the follicle and making it unrecognizable. TEE in the absence of follicular involvement, without demonstrable collagen or elastin, is reminiscent of Kyrle disease. Perforation associated with EVG-positive elastic fibers within a transepidermal canal, as seen in EPS, has also been described (72,74). Patterson et al. (75) reported a patient who had multiple lesions biopsied which variably showed histologic features of RPC, perforating folliculitis, and Kyrle disease. Combined TEE of both elastic and collagen fibers have been observed in four patients with renal disease (48), a finding which has only rarely been described in Kyrle disease or RPC (70).

Pathogenesis. RPC, EPS, and perforating folliculitis exist as distinct perforating disorders when not associated with renal disease and diabetes. At least in the setting of APD, however, the presence of various histologic patterns suggests the possibility of a common underlying mechanism (48). A nearly ubiquitous clinical feature of APD is pruritis. Certainly, lesions are often distributed in areas accessible to scratching, and reducing pruritis can lead to clearance (73). Poor blood supply secondary to diabetic microangiopathy, combined with trauma, may lead to dermal necrosis, alteration of connective tissue, and TEE (70,73,76). Others have suggested that a consequence of dialysis is the underlying cause of APD (72). Possible etiologies include disruption of metabolism of vitamins A and/or D (77) or the accumulation of a poorly dialyzable substance in the dermis (78,79). Fibronectin, a glycoprotein of the extracellular matrix, accumulates in the serum of uremic and diabetic patients. It has been suggested that transcriptional induction of fibronectin, possibly by transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) or platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), increases epithelial migration and proliferation and leads to TEE (77). APD has been reported in 5% to 11% of patients with chronic renal failure undergoing hemodialysis (49,78), and clearance of APD following renal transplant has been reported. However, it has also occurred following transplant, in patients with normal renal function (72). In addition, some cases have occurred prior to the start of hemodialysis or in patients who never underwent dialysis (49). Patterson suggests that TEE may represent a “final common pathway” of a variety of dermal and epithelial processes acting alone or in concert (70).

Differential Diagnosis. See Table 15-1.

Principles of Management. A similar topical approach to previously discussed diseases may also be reasonable for limited disease or in some clinical scenarios. In conjunction with treatment of underlying systemic disease, allopurinol, doxycycline, systemic retinoids, and narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy have been effective in treatment of APD (80).

PERFORATING CALCIFIC ELASTOSIS (PERIUMBILICAL PERFORATING PSEUDOXANTHOMA ELASTICUM)

In perforating calcific elastosis, also referred to as periumbilical perforating pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PPPXE), a gradually enlarging, well-demarcated, hyperpigmented patch or plaque is usually seen in the periumbilical region in middle-aged, obese, multiparous women with hypertension (81).

Clinical Summary. Most patients described have been African American (82). The patch or plaque is in some instances atrophic with discrete keratotic papules at the periphery (83); in other instances, it has a verrucous border (84), and in still others it has a fissured, verrucous surface throughout (85). Lesions occurring on the breast have also been described (86–88). Perforating calcific elastosis was initially regarded as EPS coexisting with pseudoxanthoma elasticum (89–93). The disorder was later shown to be distinct from EPS (84).

Four patients with perforating calcific elastosis associated with renal failure have been described (82,87,94,95). One patient demonstrated regression of the lesions with hemodialysis (82).

Histopathology. Numerous altered elastic fibers are observed in the reticular dermis. They are short, thick, and curled, and are encrusted with calcium salts, as shown by a positive von Kossa stain. They are thus indistinguishable from the elastic fibers seen in pseudoxanthoma elasticum (81). As in pseudoxanthoma elasticum, the elastic fibers are visible even in sections stained with hematoxylin–eosin, owing to their basophilia (83). The altered elastic fibers in perforating calcific elastosis are extruded to the surface either through the epidermis in a wide channel (84), or through a tunnel in the hyperplastic epidermis that ends in a keratin-filled crater (83) (Fig. 15-7A, B).

Figure 15-7 Perforating calcific elastosis. A: Degenerating elastic fibers encrusted with calcium salts in the reticular dermis surround a distorted transepidermal channel. B: The calcified fibers are in the process of being extruded through the base of the channel.

Pathogenesis. Electron microscopic examination reveals electron-dense deposits of calcium primarily in the central core of elastic fibers. Calcification of collagen bundles is also seen (86). The etiologic nature of perforating calcific elastosis has been debated. Some hypothesize it is an acquired lesion developing as a consequence of local cutaneous trauma from such factors as obesity, multiple pregnancies, ascites, or multiple abdominal surgeries (81,83,86). They cite the characteristic clinical presentation, lack of systemic manifestations, and absence of familial predisposition in most cases. The occurrence of perforating calcific elastosis in patients with renal failure may suggest that conditions resulting in an abnormal calcium phosphate product may produce abnormal calcification of elastic fibers. The occurrence of pseudoxanthoma elasticum–like eruptions in patients exposed to saltpeter (calcium–ammonium–nitrate salts) (96

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree