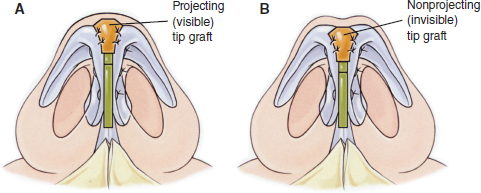

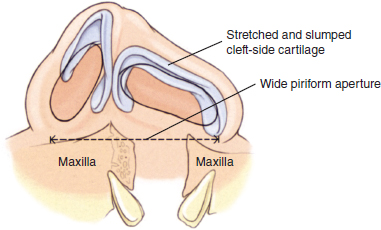

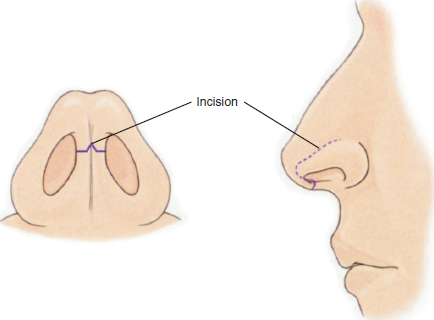

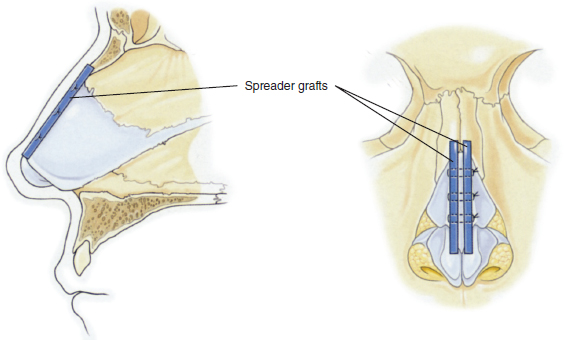

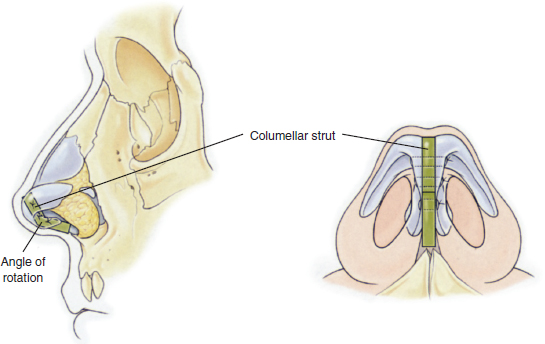

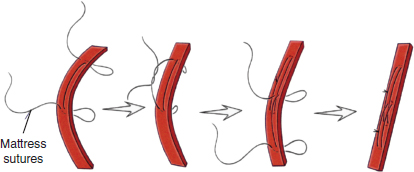

56 The cleft lip nasal deformity is the “ultimate” crooked or twisted nose; it should be addressed surgically using the well-established reconstructive principles of open septorhinoplasty to straighten a crooked nose. ○ Scarred nasal skin has a strong memory; therefore strong cartilage grafts are necessary to correct the deformity. These cartilage grafts may be harvested from the nasal septum, concha of the ear, or the costal cartilages. The septum provides strong cartilage but is in short supply, and ear cartilage is weak. Costal cartilage is the ideal material for a deformed nose covered with an inelastic nasal skin envelope stiffened by scar and requiring strong anterior projection, because it has the strength to provide architectural support and aesthetic form. ○ Cartilage grafts are used for reconstruction of the nasal tip. These include spreader grafts, columellar strut grafts, tip or cap grafts, lateral crural grafts, alar margin grafts, dorsal onlay and radix grafts, and premaxillary grafts. When the lower lateral cartilages are small, deformed, or flimsy, new alar cartilage arches can be constructed over and anchored to the existing alar cartilages. ○ The septal cartilage must be released from the deforming forces of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoids and the vomer. The posterior airway is often obstructed at the junction of these three anatomic units. ○ Complete osteotomies are required to entirely release the bony pyramid and reposition it to the midline. Bony osteotomies are required as part of the initial phase of the operation when deforming forces are “released”—before the reconstructive portion of the operation when cartilage grafts are sewn in, rebuilding the nose in the midline. Early postoperative attempts to correct a cleft lip nasal deformity often achieve a lift of the alar cartilage to the septal cartilage or to the external nasal skin, as in a Tajima repair.1 These early cartilage lifts require separating the alar cartilage from the nasal skin and cutting the cartilage loose from its attachment to the upper lateral cartilage by dividing the nearly invisible infant scroll cartilage that connects the two. This dissection creates planes of contracting scar and in some instances may do more damage to the nose than the surgery does good. Correcting the so-called slumped (or posteriorly depressed) alar cartilage by freeing and lifting it with sutures is a desperate attempt that may fall short of the current standard guiding aesthetic open rhinoplasty. At adolescence, the nasal bones, upper lateral cartilages, and septum begin to rapidly expand anteriorly and vertically. At the same time, the alar cartilages become increasingly convoluted until they take on the adult dimensions and the specific, complex, mirror-image forms that make an adult nose appear normal, deformed, beautiful, or ugly. These aesthetic judgments rarely can be made until the cartilages have grown. Often, the time for definitive reshaping of the deformed cleft lip alar cartilage is after this growth is complete. Reshaping or even repositioning the infant’s gossamer alar cartilage will succeed only when the deformity is mild. Many articles show before and after photographs of cleft lip noses of children 3 to 8 years after initial repair of their cleft lip nasal deformity. These comparisons are not entirely valid, because their noses are still infantile. The early lifts of the cleft-side alar cartilage can achieve symmetry, but only as long as the nose remains in its primordial, prepubescent state. When the nasal framework grows and assumes its mature size and shape at adolescence, nascent deformities appear. Significant secondary cleft lip nasal deformities have to be reshaped or rebuilt with cartilage grafts after the adolescent growth has occurred, at 12 to 18 years of age. However, these late rhinoplasties often are not performed. By the time an open rhinoplasty is indicated, a cleft lip patient has adjusted psychologically to a certain permanent facial deformity and the stigma it carries. Furthermore, the pediatric plastic surgeon that has cared for these patients since birth is not usually—with some exceptions—highly skilled at adult open rhinoplasty. Because these grownup cleft lip patients accept their deformity as “the best that can be expected,” definitive correction of their twisted noses may never be completed. The cleft lip alar cartilage (in both unilateral and bilateral deformities) is sometimes referred to as “slumped” (depressed posteriorly). In truth, it is stretched across an abnormally wide piriform aperture (Fig. 56-1). It is attached at both ends to bone, the medial end to the premaxilla and the lateral end to the maxilla with a tight leash of sesamoid cartilages. In some cases, the piriform aperture is so wide that no amount of lifting and tugging can move the alar cartilage arch anteriorly so that it projects normally. Even releasing the lateral end of the lateral crus from the maxilla by transecting the chain of sesamoid cartilages will not allow the alar arch to move forward. The fibrocartilage of the alar arch is tightly fused to the skin that lines the nasal vestibule. Both the lining skin and the lateral crus must be cut loose from the bony edge of the piriform aperture before the lateral crus can be advanced anteriorly. Yet even this radical release may not allow the alar cartilage to project anteriorly, because in many cases the alar cartilage is hypoplastic. The alar cartilage of the cleft side often does not attain the size and form of the alar cartilage on the opposite normal side. The surface area of the alar lobule of the cleft side of the nose is often only half the surface area of the contralateral normal ala. As the nose grows at adolescence, the true magnitude of this hypoplasia becomes apparent. The middle and lateral crura are slumped and hypoplastic. The fibrofatty tissue and skin envelope of the cleft side of the nose are also hypoplastic. In many cases, no amount of lifting and release of the middle and lateral crura can make the hypoplastic alar cartilage project normally. In these cases, open rhinoplasty, performed after the nose has reached its adult proportions, allows the surgeon to construct a new alar cartilage framework over the existing hypoplastic alar cartilage—in essence, to build a new tip for the nose. Mild asymmetries can be corrected with conventional open rhinoplasty techniques used to reshape the alar cartilage with transdomal, interdomal, and lateral crural sutures. Severe deformities, in which one or both alar cartilages are hypoplastic, require reconstruction of the entire nasal tip with cartilage grafts. These grafts are harvested from the nasal septum, conchae of the ears, or costal cartilages. Early manipulations of the alar cartilage should be minimal, because such manipulations provide limited and temporary benefit. The cartilage should not be cut or detached from the vestibule skin lining and probably should not be cut loose from the scroll that joins it to the upper lateral cartilage. Early lifting can fully correct only mild deformities. For major cleft lip nasal deformities, a definitive operation will be necessary at about 14 to 18 years of age if the adult nose is to be symmetrical and of normal appearance. Fig. 56-1 In cleft lip deformities, the alar cartilage is slumped and stretched over an abnormally wide piriform aperture. The operation of choice is open rhinoplasty to reshape the septal and alar cartilages under direct vision or to build a new nasal tip with cartilage grafts. Cartilage grafts may be harvested from the nasal septum, concha of the ear, or the costal cartilages. Each donor source has advantages and disadvantages. The septum provides strong hyaline cartilage, but it is in short supply. Ear cartilage is fibrocartilage and therefore weak. Septal or ear cartilage should be used only when the cleft lip nasal deformity is not severe. Costal cartilage is the ideal material for a severely deformed nasal tip that needs a strong anterior projection and is covered with an inelastic nasal skin envelope stiffened by scar. Gunter2 thought that only costal cartilage has the strength to provide the architectural support and aesthetic form necessary for severely deformed noses. The edges of a symmetrical incision are easy to line up at closure. Thus many surgeons use a transverse columellar incision with a central dentate flap. The proper position for this incision is between the anterior one third and the posterior two thirds of the columella (Fig. 56-2), not at the base of the columella. A normal columella has an hourglass shape when viewed from below—wider at the top and bottom than at the middle. The incision lies at the narrowest point, around the junction of the upper and middle thirds. Placing the incision at the base of the columella will not hide the scar in a natural, shadowed crease. In truth, there is no crease at the base of a normal columella, but rather a smooth, open, obtuse angle between the lip and nose. Furthermore, the base is the most anterior-facing part of the columella, so a scar at the base will easily be seen on frontal view. Finally, placing the open rhinoplasty scar at the base of the columella creates an unduly long columella flap, which is less vascular and subject to necrosis, even when performed by experienced rhinoplasty surgeons. Therefore the open rhinoplasty incision should be placed anteriorly on the columella, not at its base. Fig. 56-2 The transverse columellar incision for open rhinoplasty should be made between the anterior third and posterior two thirds of the columella, not at its base. If the columellar incision is closed meticulously, the scar is rarely seen after a few months. Using 3.5× magnifying loupes, the incision is closed with one to three subcuticular 6-0 clear sutures and nine to eleven 7-0 monofilament skin sutures. To prevent stitch marks, the sutures should be removed within 2 to 4 days after surgery and be replaced with narrow (1/16-inch to 1/24-inch) tapes, held with gum mastic adhesive. The sutures should be removed extremely gently. As Sir Harold Gillies said, “Do not lift the patient up by his stitches.”3 When the flap of skin and fat has been elevated off the perichondrium and periosteum of the nasal cartilages and bones, the stretched and slumped lateral crus can be freed from its attachments to the maxilla. Reshaping the alar cartilage arch on the cleft side without extensive freeing of the cartilage may not be possible, for two reasons: (1) The piriform aperture of the nose above the cleft maxilla is abnormally wide.1 The alar cartilage is stretched across this wide bony cleft between the premaxilla and the lateral maxilla. Freeing the lateral crus of the alar cartilage from the maxilla may not give the cartilage enough mobility. The tight skin lining of the vestibule must also be cut loose from the bony edge of the piriform aperture so that the nasal vestibule and alar margin may be projected anteriorly and reshaped. This is accomplished by cutting the vestibule skin lining free just at the anterior edge of the bony piriform aperture or by releasing it by cutting slightly posterior to that edge so that the lining defect lies on the lateral bony sidewall of the nose.2 (2) The alar cartilage may be small and flimsy. In this case, attempts to give it a normal shape, size, and anterior projection are futile. The cartilage should be buttressed with strong grafts of septal or costal cartilage or replaced with a new arch of cartilage manufactured from the septum, concha, or rib cartilage. The deformed alar cartilage is released from its posterior attachments. When it is of nearly normal size, it can be reshaped and braced with cartilage grafts using the techniques used in cosmetic open rhinoplasty. If the alar cartilage is hypoplastic, however, then one or both alar cartilages must be reconstructed using cartilage graft material from the septum, ear, or rib. In either case, cartilage grafts are the key to achieving a symmetrical, projecting, and normal-appearing nasal tip. The best donor material for reconstruction of the alar cartilage is septal or costal cartilage. Cartilage from the ear is too soft. The skin of a cleft lip nose has an intrinsic form, a “memory” of the shape of the cleft lip nasal deformity. That is, if one were to remove the skin from a cleft lip nose and place it on a table, the skin would stand up—even without any cartilage support—and retain the shape of the cleft lip nose. Plastic surgeons have underestimated this intrinsic memory of the nose that characterizes a somewhat rigid nasal skin envelope. Furthermore, the cleft lip nose has an even more rigid form than a normal nose because of the subcutaneous layer of scar tissue from previous operations. A strong cartilage framework must be constructed in the course of open rhinoplasty to overcome the stiff skin envelope of the cleft lip nose and force the skin into a normal, natural shape. When the alar cartilage on the cleft side is of nearly normal or normal size, sutures can reshape it to match the contralateral normal cartilage. Cartilage grafts harvested from the septum or rib are necessary to hold the reconstructed alar cartilage in its new, normal shape, because several strong forces will try to deform it again. As mentioned, the deformed skin envelope of the cleft lip nose has its own intrinsic shape that will force the nasal tip back to its original cleft lip shape. Also, after rhinoplasty, a sheet of contracting scar tissue will form beneath the skin envelope of the nose. This tissue will contract centripetally, further deforming the newly reconstructed nose. Therefore strong cartilage grafts are necessary to brace the alar cartilages and hold the nasal skin envelope in its normal dimensions and shape. The grafts are the same as those commonly used in cosmetic open rhinoplasty: In addition to those five types of grafts inside the nasal tip, three types of grafts outside the nasal tip can also be helpful. Dorsal onlay grafts and radix grafts may be used to raise the dorsum or camouflage irregularities of the dorsum and radix. Furthermore, a premaxillary graft beneath the nasal floor can move the base of the nose forward and open an acute lip-nose angle. Two strips of cartilage are harvested from the nasal septum, the concha, or the fifth, sixth, seventh, or eighth costal cartilages. The grafts are carved to be approximately 1.7 to 3.0 cm long, 4 mm deep, and 1.5 mm wide. These strips are used to spread the upper lateral cartilages apart and thus widen the anterior part of the nasal airway and the nasal dorsum itself (Fig. 56-3). The use of spreader grafts is the most effective way to permanently and predictably straighten a crooked nose. To place spreader grafts, the mucosal vaults of the nose are first separated intact from cartilaginous septum. The dorsal septum is shaved smooth and lowered, if indicated. The midline of the upper lip is marked; this will be the midline for the nose. The teeth may have a separate and different midline. If needed, the central septal cartilage is harvested for graft material. A supportive L-shaped strut 1.2 to 1.5 cm wide is retained for nasal support. Medial and lateral nasal osteotomies are performed. The crooked septal cartilage is then compressed between the two spreader grafts to straighten the septum on the AP view. When the septum is straight and in line with the midline of the upper lip, the spreader grafts are fastened in place with three No. 27 hypodermic needles that pass through the three layers of cartilage (the two spreader grafts and the septum). With the septal cartilage straight in the midline, the three layers are sutured tightly together with 4-0 monofilament mattress sutures. Spreader grafts may also be positioned anterior to the dorsum of the septal cartilage to raise the inferior end of the dorsal septum and increase the nasal facial angle (the opposite purpose of a radix graft). Finally, the upper lateral cartilages are trimmed and anchored to the straightened midline septum with 5-0 monofilament mattress sutures passed through all five layers of cartilage (the upper lateral cartilages, the spreader grafts, and the dorsal septal cartilage). A crooked nose straightened in this way will remain in the midline despite the forces of scar contraction that act upon the nose in the postoperative period. Next, the framework for the nasal tip is constructed to project 6 to 8 mm above the dorsal line of the septal cartilage. Fig. 56-3 Spreader grafts permanently straighten a crooked nose. They also spread the upper lateral cartilages and widen the nasal airway and the nasal dorsum itself. A strut of cartilage should be placed between the medial and middle crura of the alar cartilage in an open rhinoplasty. This columellar strut stiffens the alar cartilage and supports the nasal tip against forces that deproject the nasal tip in the postoperative period. That is, after a rhinoplasty, a sheet of scar tissue is deposited between the nasal skin and the underlying cartilages. Starting approximately 3 weeks after surgery, myofibroblasts within the scar begin to contract with a strong force. The sheet of scar tissue tightens like a drumhead, forcing the nasal tip posteriorly against the facial plane. Tip projection can be lost. A columellar strut of cartilage (or bone), as well as lateral crural grafts, form a tripod that resists the deprojecting force.4 A proper columellar strut should have an angle that simulates Sheen’s columellar-lobular angle of rotation of approximately 50 degrees.5 If the strut is not angled, the columella may tend to be straight, giving the resulting nose a beaklike quality. Fig. 56-4 shows the columellar strut and its optimal angle of rotation. Fig. 56-4 The columellar strut stiffens the alar cartilages and supports the nose against forces that deproject the nasal tip after open rhinoplasty. The strut should be angled to create a normal columellar-lobular angle of rotation. Fig. 56-5 A warped columellar strut can be straightened by tightening mattress sutures against the curve. Septal cartilage, because it is straight, is the best donor cartilage for a columellar strut. Auricular cartilage has an intrinsic curve, and costal cartilage tends to warp. However, placing mattress sutures along curved or warped strips of ear or costal cartilage and tightening the sutures against the curve (like stringing a bow on the outside of its curve) can straighten these cartilage struts (Fig. 56-5). The columellar strut is inserted into a pocket that extends deep to the feet of the existing medial crura. Some surgeons actually suture the strut to the anterior nasal spine.6 The base of the strut is fixed to the feet of the medial crura with a gut mattress suture passed through all layers of the membranous septum. This suture fixes the height and symmetry of the alar cartilage arches. The strut is then sutured to the cephalic edges of the existing medial and middle crura of the alar cartilages with several 5-0 monofilament sutures, and this gives the new nose a stiff, strongly supported tip structure. Sheen tip grafts give strength to the alar cartilages and may add projection to the nasal tip.7 They can be carved from septal, conchal, or costal cartilage, and even from preserved human allograft cartilage. In silhouette, the grafts look like a shield or a golf tee. A tip graft generally measures 12 to 16 mm in length and 9 to 11 mm across the top. Its edges are chamfered or smoothed.

Definitive Rhinoplasty for Adult Cleft Lip Nasal Deformity

Gary C. Burget

KEY POINTS

THE CLEFT LIP ALAR CARTILAGE

RHINOPLASTY

The Incision

Freeing the Deformed Alar Cartilage

Two Techniques for Supporting the New Nasal Tip

Cartilage Grafting When the Cleft Alar Cartilage Is of Normal Size

Spreader Grafts

Columellar Strut Grafts

Visible and Invisible Tip Grafts and Cap Grafts

Plastic Surgery Key

Fastest Plastic Surgery & Dermatology Insight Engine