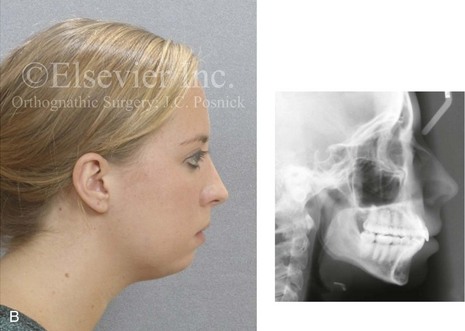

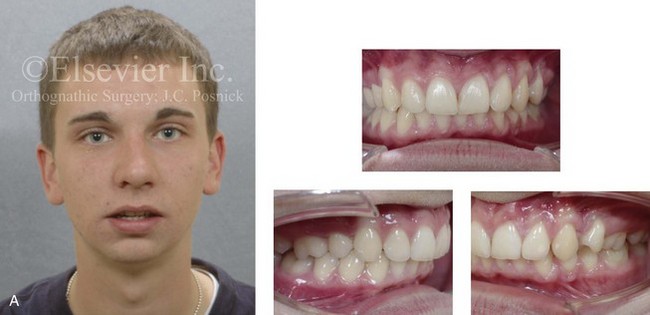

3 The term dentofacial deformity refers to significant deviations from normal proportions of the maxillomandibular complex that also negatively affect the relationship of the teeth within each arch and the relationship of the arches with one another (occlusion).2,4,5,8,11,14,15,17,18,21,22,25,27,31,36,37,40,52,54 The affected individual will have varied degrees of compromise in head and neck functions related to breathing, swallowing, speech articulation, chewing, and lip closure/posture. Effects on the temporomandibular joints, the periodontium, and the teeth themselves may also occur.24,25,28,33,34,38,55 The presenting facial disproportion will, in general, have at least some negative effects on psychosocial health.16,39,56,57 Racial variations with regard to the incidence of facial dysmorphology and the resulting malocclusion are also known to occur.59,64 Definitions of acceptable levels of deviation from normal continue to be questioned by both clinicians and patients.7,26,30,32,35,58,61,62 Over the years, the National Center for Health Statistics has collected data and the Research Council has held multidisciplinary conferences to focus attention on these issues.6,12,19,20,29,41-51,53,63 Surgery to reposition the jaws (i.e., an orthognathic procedure) as part of an interdisciplinary approach is often recommended to manage the related skeletal, dental, and soft-tissue dysfunctions and concerns.3,13,23,60,66 Speech therapy, dental work, orthodontics, and surgical procedures alone are generally inadequate as isolated treatment modalities. Facial disproportion observed in a child may at times be self-correcting. For example, apparent mandibular deficiency that is present before the pubertal growth spurt may normalize. In some cases, the maxilla or mandible may be induced to grow a few millimeters, more or less, through dentofacial orthopedics. However, major transformation of the jaws with the use of growth-modification techniques cannot be expected. Proffit has pointed out that, even with the well-intended aim of dentofacial orthopedics to alter jaw growth, as a result of anchorage requirements and biologic realities coupled with the practical desire of the orthodontist to “correct the occlusion,” the treatment generally results in the displacement of the teeth in the direction of correcting the occlusion rather than the jaw relationships.53 The term dental compensation for the skeletal discrepancy is universally understood to explain this treatment approach. Orthodontic-introduced dental compensation for the occlusion will hinder the eventual skeletal (orthognathic) correction if this is later required or requested. Informed consent from the patient or his or her family is strongly recommended before embarking on a compromised treatment plan. For example, if a child is recognized to have an underdeveloped mandible with a Class II malocclusion and standard growth modification is attempted, it may be difficult for the orthodontist to prevent at least some retraction of the upper incisors and the forward displacement of the lower teeth. This may result in an “improved” occlusion, but it may also potentially involve long-term negative effects on periodontal health (e.g., labial cortical bone stripping), the airway (e.g., retroglossal obstruction), and facial aesthetics (e.g., a weak profile).39,56,57 It also compromises the option of an orthognathic correction with the need to first “undo” the dental compensations through “redo” orthodontics (Fig. 3-1). Figure 3-1 A 21-year-old woman with a primary mandibular deficiency growth pattern requested a surgical consultation for a “weak chin.” During her early teenage years, she underwent unsuccessful growth modification in an attempt to stimulate the forward projection of the mandible. This was followed by an orthodontic camouflage approach. The mandibular anterior dentition was flared forward. The history was significant for restless sleeping and a degree of daytime fatigue, which are suggestive of obstructive sleep apnea. Examination confirmed a retrognathic mandible with a Class II malocclusion. The mandibular incisors were crowded and procumbent. The family had hoped that a “chin implant” would be effective to manage the aesthetic effects. A sleep study confirmed obstructive sleep apnea (respiratory disturbance index = 18/hour). An orthognathic approach (Le Fort I, Sagittal splits, Osseous genioplasty) with redo orthodontic treatment including lower bicuspid extractions was recommended as the preferred method to improve the airway, to achieve long-term dental health, and to enhance facial aesthetics. A, Frontal facial and occlusal views. B, Profile facial view and lateral cephalometric radiograph. In the growing child who presents with a Class II malocclusion pattern, an active treatment approach is often offered by the orthodontist. This approach may attempt to alter jaw growth and to correct the occlusion by means of the following: (1) functional appliance use (e.g., Frankel, Twinblocks) to stimulate sagittal growth of the mandible; (2) the possible extraction of maxillary premolars with orthodontic incisor retraction; (3) the use of headgear to restrain maxillary sagittal growth; and (4) the orthodontic forward displacement of the lower anterior teeth (Fig. 3-2). With the use of this approach, favorable facial results will be seen in only a very specific patient subgroup that includes those patients with true maxillary dental protrusion and a limited degree of mandibular retrusion. In these cases, the extraction of maxillary premolars with the retraction of the incisors to a corrected inclination in combination with the minimal forward displacement of the lower teeth may result in both favorable occlusion and acceptable facial aesthetics. Figure 3-2 A 20-year-old man with a primary mandibular deficiency growth pattern requested a surgical consultation for a “weak chin.” During his early teenage years, he underwent unsuccessful growth modification in an attempt to stimulate the forward projection of the mandible. This was followed by an orthodontic camouflage approach that included maxillary first bicuspid extractions to retract the anterior teeth. In addition, the mandibular anterior dentition was flared forward. His history was significant for heavy snoring, restless sleeping, and a degree of daytime fatigue, all of which are suggestive of obstructive sleep apnea. Examination confirmed a retrognathic mandible with a molar Class II deep bite malocclusion. The mandibular incisors were crowded and procumbent. The family had hoped that a “chin implant” would be effective to manage the aesthetic effects. A sleep study was recommended. An orthognathic approach (Le Fort I, Sagittal splits, osseous genioplasty) with redo orthodontic treatment was suggested as the preferred method to improve the airway, to achieve long-term dental health, and to enhance facial aesthetics. A, Frontal facial and occlusal views. B, Profile facial view and lateral cephalometric radiograph. As part of a large-scale evaluation of the health of the U.S. population, a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) was carried out between 1989 and 1994.53 Starting with a sampling of 14,000 individuals, estimates of the incidence of malocclusion and its severity were made. The sample of individuals was carefully selected to provide weighted estimates for an approximate 150,000,000 people between the ages of 8 and 50 years who were members of black, white, and Latino American racial and ethnic groups. Those individuals outside of that age range (i.e., those younger than 8 years and older than 50 years), Native Americans, those living on military reservations, and some other specific population groups were excluded from this study. Data collected included the following: • The alignment of the incisor teeth • The horizontal position of the incisors (i.e., overjet or reverse overjet) • The vertical overlap of the incisors (i.e., deep bite or open bite) • The presence of posterior crossbite This study provides useful information about preadolescent children (8 to 11 years old), adolescents (12 to 17 years old), and adults (18 to 50 years old) with reference to how the teeth fit together and, by inference, the prevalence of dentofacial deformities. When interpreting the data collected for the NHANES III study, it is important to consider that at least some degree of dental compensation for an existing jaw deformity normally occurs during growth and is expected to have been present at the time that the study measurements were taken. Therefore, it is unlikely that either the moderate or greater values of positive overjet or the mild to moderate values of negative overjet measured in the NHANES III study were found in individuals with “normal” jaw relationships. It would be safe to assume that any individual in the study with more than 7 mm of positive overjet has a jaw discrepancy that is characterized by mandibular deficiency (see Chapter 19). In addition, those with 2 mm or more of reverse overjet are assumed to have elements of maxillary deficiency in combination with relative mandibular excess (see Chapter 20).

Definition and Prevalence of Dentofacial Deformities

Prevalence of Jaw Deformities and Malocclusion

U.S. Population Survey

The Horizontal/Sagittal Dimension

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Definition and Prevalence of Dentofacial Deformities