10. Decreasing Complications in Aesthetic Surgery

Edward H. Davidson, Zoe Diana Draelos, Bridget Harrison, Ibrahim Khansa, Jeffrey E. Janis

■ Successful outcomes in aesthetic surgery and nonoperative cosmetic procedures demand meticulous preparation and aftercare to ensure optimal results and minimize risk of complications.

■ Preparation and aftercare regimens are commonly procedure, technique, and practitioner dependent, but general principles and considerations may be applied.

■ Involving patients in their own management before and after cosmetic interventions promotes understanding, empowers them to invest in their own results, and may help to manage expectations.

PREOPERATIVE MEASURES TO REDUCE COMPLICATIONS

COMORBIDITIES

■ Elective aesthetic surgery patients are usually healthy. The presence of chronic disease (including diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hepatic or renal dysfunction, cancer) necessitates preoperative medical clearance by the patient’s primary care physician or specialist.

• Diabetes: Poor glycemic control places diabetic patients at increased risk of surgical site infection and delayed wound healing.1,2

• Hypertension: Uncontrolled hypertension increases risk of bleeding and hematoma in all aesthetic procedures, and visual loss after blepharoplasty.3

• Coagulopathy: Hematologic consultation should be considered for patients with history of coagulopathy or venous thromboembolism (VTE).

• Most elective plastic surgery procedures performed in the United States are performed on white females. Factor V Leiden gene is found as a heterozygous mutation in 3%-7% of white females and results in a sixfold increase in the risk of VTE.

• VTE risk is increased if combined with cancer, travel, immobilization, use of oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, and estrogen receptor antagonists.

■ In low-risk ambulatory plastic surgery patients, preoperative laboratory testing is costly, associated with limited clinical benefit, and may be eliminated with significant cost savings.4

■ Mental health: A patient’s mental health should be preoperatively assessed and appropriately addressed before proceeding with any elective procedure.5 Patients with mental health conditions—whether psychiatric disorders, such as body dysmorphic disorder or substance abuse diagnoses—who undergo outpatient aesthetic surgery seek hospital-based acute care within 30 days postoperatively three times more often than patients without a mental health condition (see Chapter 1).

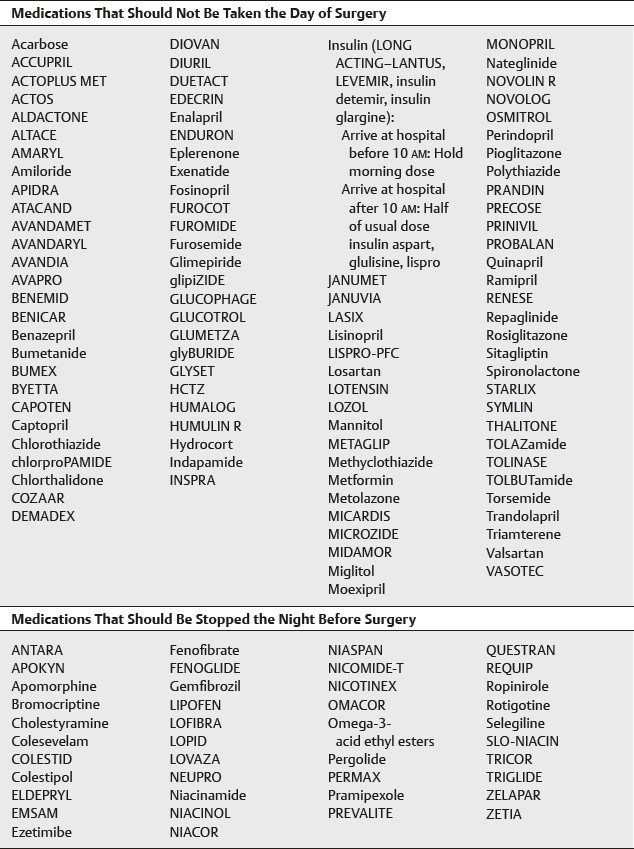

■ Medications: Every patient’s medications must be carefully reviewed. Table 10-1, although not exhaustive, lists medications associated with postoperative complications and/or interference with some anesthesia and may require discontinuation or special precautions.

Table 10-1 Medications Requiring Discontinuation or Special Precautions

SUPPLEMENTS6,7 (see Chapter 6)

■ Use of herbal medicines and supplements is more prevalent in the cosmetic surgery population than in the population at large (49% versus 42%, respectively).6

■ Nutritional supplements are not routinely recommended in lieu of a healthy, well-balanced diet.

■ 60%-72% of patients do not report use of supplements.7

■ Many herbal medicines and supplements are cited for adverse reactions and should not be taken for 2-3 weeks before and after surgery8 (Box 10-1), according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Box 10-1 HERBS AND SUPPLEMENTS TO AVOID TWO TO THREE WEEKS BEFORE AND AFTER SURGERY

Bilberry

Cayenne

Chondroitin* (postoperative bleeding)

Dong quai

Echinacea* (potentiates barbiturate and halothane toxicity, allergic reaction, immunosuppression)

Ephedra* (hypertension and cardiac instability)

Feverfew

Fish oil

Garlic* (perioperative bleeding)

Ginko* (postoperative sedation, perioperative bleeding)

Ginger

Ginseng* (perioperative bleeding)

Glucosamine* (hypoglycemia)

Goldenseal* (volume depletion, postoperative sedation, photosensitization)

Green tea

Guarana

Hawthorne

Kava kava* (postoperative sedation)

Licorice root

Ma huang

Meadowsweet

Melatonin

Milk thistle* (volume depletion)

Niacin

Red clover

Saw palmetto

St. John’s wort

Turmeric

Valerian

Vitamin E

Yohimbe

White willow

*Top ten herbal and supplemental medications used by cosmetic patients.8

Bromelain

■ Pineapple extract

■ Reported to reduce pain, edema, inflammation, bruising, and platelet aggregation and to potentiate antibiotics

■ 500-1500 mg/day taken in divided doses 1-2 weeks preoperatively and postoperatively

■ More randomized, controlled clinical trials necessary to determine its clinical potential9

Arnica

■ Reported to reduce ecchymosis and edema postoperatively; contradictory evidence10

■ May be equivalent to steroids in reducing postrhinoplasty edema when used postoperatively11

Vitamin A

■ Impairment of wound healing caused by use of corticosteroids can be reversed by the oral administration of vitamin A (retinoic acid), use 15,000 IU daily for 7 days; however, this is not common surgical practice.12

Vitamin B

■ Patients with true deficiencies of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), vitamin B1 (thiamine), or vitamin B2 (riboflavin) may have wound-healing problems and benefit from supplementation.13

■ Vitamin B–deficient patients may have other nutritional deficiencies and may be poor surgical risks.

Vitamin C

■ Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) results in inability to cross-link collagen fibers and decreased wound tensile strength, which may be reversed by vitamin C supplementation.14

■ Vitamin C deficiency is extremely rare and is an indicator of otherwise poor health and poor surgical candidates.

SURGEON-PATIENT COMMUNICATION

■ Patient satisfaction is highly dependent on the initial consultation. This interaction not only affects the patient’s impression of the physician, but can also influence satisfaction with surgical and overall outcomes.15

■ Behaviors that lead patients to not recommend surgeons to friends and family members include failure to adequately explain medical condition, failure to show interest in the patient, failure to ask if the patient has questions, and failure to answer questions.16

LIFESTYLE MODULATION

■ There are relative and absolute contraindications for office-based aesthetic surgery that need to be addressed with the patient before the procedure (Box 10-2).

Box 10-2 RELATIVE AND ABSOLUTE CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR OFFICE-BASED AESTHETIC SURGERY

Patient-Related Factors

Poorly controlled systemic disease

Moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea

Morbid obesity

Myocardial infarction in last 6 months

Cerebral vascular accident in last 3 months

Lack of an adult escort

Implantable defibrillator or pacemaker

Unstable psychological disease

Acute substance abuse

History of malignant hyperthermia (if use of triggering agent planned)

History of end-stage renal failure, undergoing dialysis

Sickle cell disease

Myasthenia gravis

Younger than 3 years old

Procedure-Related Factors

Liposuction >5,000 ml

Tumescent solution >5,000 ml

High-volume liposuction with second procedure

Multiple procedures with abdominoplasty

Anticipated blood loss >500 ml in adults

Surgical duration >6 hours

Smoking

■ Cigarette smoking has a well-established negative effect on the wound-healing process, resulting in tissue hypoxia and ischemia.17

■ A common recommendation is a 4-week period of no smoking both before and after surgery.18

■ Pharmacologic (nicotine replacement, bupropion) and nonpharmacologic (counseling, behavioral therapy, hypnosis, psychotherapy, electrical stimulation) smoking cessation strategies should be considered.

■ If noncompliance is suspected, a urine cotinine (a nicotine metabolite) test is recommended preoperatively.19,20

■ Alternatively, a blood test can measure multiple nicotine metabolites (cotinine, anabasine, nornicotine) to give a clearer picture of active smoking, passive smoke inhalation, and use of nicotine replacement therapies.

TIP: A urine cotinine test is a simple and inexpensive measure to determine whether a patient has smoked within the last 4 days.

Alcohol

■ Potentially alcohol-induced disorders of the liver, pancreas, and nervous system

■ Heavy drinking also affects cardiac function, immune capacity, hemostasis, and metabolic stress response, and induces muscular dysfunction.

■ May be associated with other nutritional deficiencies previously discussed

■ Dose-response relationship between alcohol intake and an increase in postoperative morbidity

• Complication rate is about 50% higher in patients who drink 3-4 drinks per day compared with 0-2 per day.21

■ Recommend decreasing and even abstaining from alcohol 1-2 weeks preoperatively and postoperatively to decrease risk of perioperative bleeding.22

Diet

■ The following foods may potentiate bleeding, and some physicians advise decreased intake 1-2 weeks before and after surgery (Box 10-3).

Box 10-3 FOODS THAT MAY POTENTIATE BLEEDING

Avocados

Apples

Apricots

Blackberries

Cherries

Cucumbers

Currants

Dewberries

Fish (especially salmon)

Garlic

Gooseberries

Grapefruit

Grapes

Lemons

Melons

Nectarines

Onions

Oranges

Peaches

Peppers

Plums

Potatoes

Prunes

Raisins

Raspberries

Root beer

Shellfish

Soybeans

Spicy foods

Strawberries

Sunflower seeds

Sweet potatoes

Tomatoes

Wheat germ oil

DECOLONIZATION AND SKIN ANTISEPSIS

■ Surgical site infection can be a devastating complication of aesthetic surgery, especially when implanting a prosthetic material (e.g., breast augmentation).

■ Staphylococcus aureus is the leading cause of surgical site infection, and the prevalence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) surgical site infection is increasing.

■ Presurgical decolonization and skin antisepsis have been demonstrated to decrease surgical site infections drastically, particularly in cardiac and orthopedic surgery implant-based procedures, and support is emerging for similar practice in plastic surgery.23–25

■ Decolonization and skin antisepsis protocol:

• Two to 4 weeks before surgery, patients who may have an increased likelihood of MRSA infection (e.g., history of infection, health care worker, immunocompromised) are screened for S. aureus nasal carriage as outpatient procedures, with samples collected from both nares on a single swab. (The association with nasal carriage of S. aureus and subsequent infection is well established.26,27)

• Patients with nasal cultures positive for S. aureus are instructed to apply 2% mupirocin nasal ointment twice daily to both nares and to bathe with chlorhexidine (40 mg/ml Hibiscrub) daily for 5 days immediately before the scheduled surgery.

• Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis: Patients with a history of MRSA infection or type I allergy to penicillin and patients who are MRSA carriers receive vancomycin 1 g 60 minutes before surgery; all others receive cefazolin 2 g 30-59 minutes before surgery.2

DVT RISK ASSESSMENT (see Chapter 11)

■ The 2005 Caprini Risk Assessment Model stratifies patients by risk and guides prophylaxis decisions. Patients at high risk (score >8) should be considered for postoperative chemoprophylaxis.28

■ Overall, postoperative enoxaparin does not increase rates of reoperative hematoma.12

INTRAOPERATIVE MEASURES TO REDUCE COMPLICATIONS

■ The World Health Organization has developed a guideline of items to prevent mortality and postoperative complications. These include three phases (sign in, time out, and sign out) (Box 10-4).

Box 10-4 ELEMENTS OF THE SURGICAL SAFETY CHECKLIST

Phase 1: Sign In

Before anesthesia, team members verbally note or confirm the following:

• Patient has verified his or her identity, verified the surgical site, verified the procedure, and given consent.

• Surgical site has been marked (if applicable).

• The pulse oximeter is attached to the patient and functioning.

• Team members are aware of patient allergies (if applicable).

• Airway and risk of aspiration have been assessed; appropriate equipment and assistance are available.

• Adequate access and fluids are available if blood loss is anticipated and expected to be more than 500 ml (or 7 ml/kg of body weight for children).

Phase 2: Time Out

Before incision, team members verbally note or confirm the following:

• All team members introduce themselves by name and role.

• Patient has verified his or her identity, verified the surgical site, verified the procedure, and given consent.

• A review of anticipated critical events is completed by team.

• Surgeon describes critical or nonroutine steps, expected duration of the procedure, and anticipated blood loss.

• Anesthesia team reviews patient-specific concerns.

• Nursing team confirms sterility of instrumentation, availability of equipment, and any other anticipated concerns.

• Antibiotic prophylaxis is confirmed to have been administered 60 minutes prior to incision (if applicable).

• All essential imaging results are confirmed to be present, and for the correct patient.

Phase 3: Sign Out

Before the patient leaves the operating room, team members verbally note or confirm the following:

• Nursing team reviews all of the following with the entire team:

– Name of the procedure performed

– Confirmation of needle, sponge, and instrument counts (as applicable)

– Labeling of all specimen with the patient’s name

– Any equipment issues that will need to be addressed

• Surgeon, anesthesia team, and nursing team all verbally note the key concerns for the patient’s recovery and care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree