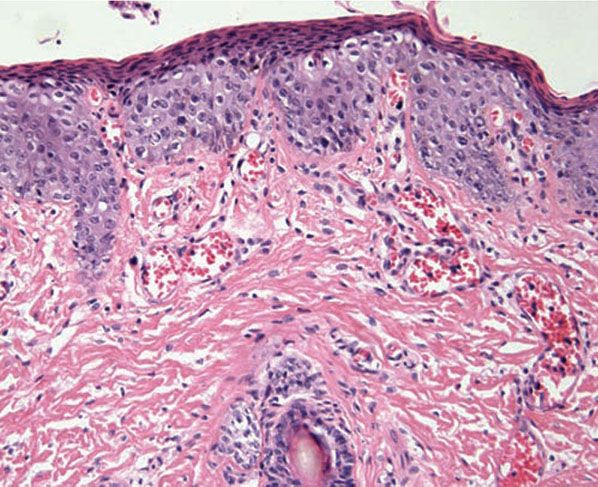

Figure 16-1 Necrolytic migratory erythema (glucagonoma syndrome). The lower portion of the stratum malpighii appears viable, whereas the upper portion shows necrolysis or “sudden death.” The necrolytic portion manifests cytoplasmic eosinophilic homogenization with pyknotic nuclei.

Pathogenesis. Patients with glucagonoma have sustained gluconeogenesis, resulting in a negative nitrogen balance, with protein amino acid degradation, even of epidermal proteins (47). In addition to glucagonoma, necrolytic migratory erythema has been reported with hepatic cirrhosis (48), jejunal adenocarcinoma with hepatic dysfunction, hepatitis B (49), malabsorption with villous atrophy (50), opiate dependency (51,52), and myelodysplastic syndrome (53). Glucagon levels may be normal. A comparable syndrome in dogs develops in the setting of diabetes mellitus and hepatic cirrhosis (46). In all of these conditions, malabsorption and diarrhea lead to isolated deficiencies of certain essential fatty acids, zinc, and amino acids. The pathophysiology may reflect in part a phospholipid fatty acid abnormality in cells due to defective Δ6-desaturase enzyme, which is known to be inhibited by zinc deficiency and excess alcohol intake. In patients with unresectable glucagonoma who manifest necrolytic migratory erythema, infusion of amino acids has resulted in rapid clearing of the cutaneous lesions (54). There is an interesting subgroup of patients with necrolytic erythema in whom the lesions are primarily confined to the dorsum of the feet. These cases are associated with hepatitis C and fall under the designation of necrolytic acral erythema (55). The dermatitis responds to a combination of antiviral therapy and zinc.

Differential Diagnosis. The histopathology is similar to that of other nutritional dermatoses, namely, acrodermatitis enteropathica and pellagra. Other dermatoses associated with hyperkeratosis, a maturation disarray, and/or scattered degenerating keratinocytes include graft-versus-host disease, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and toxic/irritant reactions, particularly those that are photo-induced.

Principles of Management. Some patients may respond to parenteral zinc supplementation.

Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acrodermatitis enteropathica, first described in 1942 (56), is transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait, resulting in defective intestinal absorption of zinc (57).

Clinical Summary. The condition usually manifests in the first 4 to 10 weeks of life in bottle-fed infants as an acral and periorificial eruption with intractable diarrhea and diffuse partial alopecia. The skin exhibits areas of moist erythema, occasionally associated with vesiculobullous and/or pustular lesions (58). Untreated cases eventuate in death from malnutrition and infection because of immunologic defects reflecting zinc deficiency, the latter including decreased natural killer cell activity, impaired delayed-type hypersensitivity, and thymic atrophy (59). Paronychia, stomatitis, photophobia, blepharitis, conjunctivitis, corneal opacities, and hoarseness are additional manifestations. An acquired form occurs in patients receiving intravenous hyperalimentation with low zinc content (60), in infants who are fed breast milk low in zinc (61), in patients with Crohn disease, in patients with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (62), in patients with status post-pancreaticouodenectomy (63), and in the setting of AIDS nephropathy when proteinuria eventuates in excessive loss of protein-bound zinc (59).

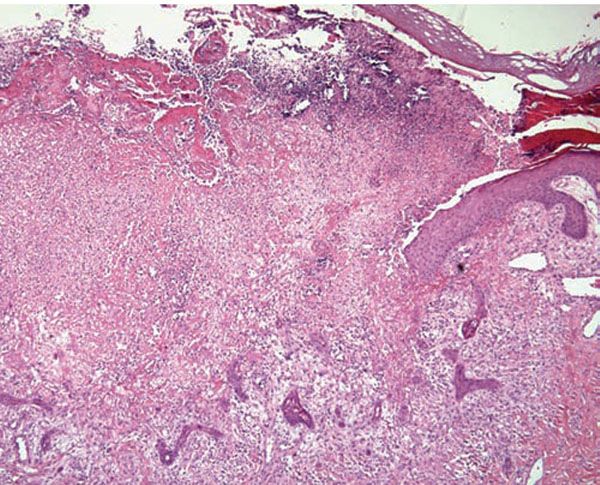

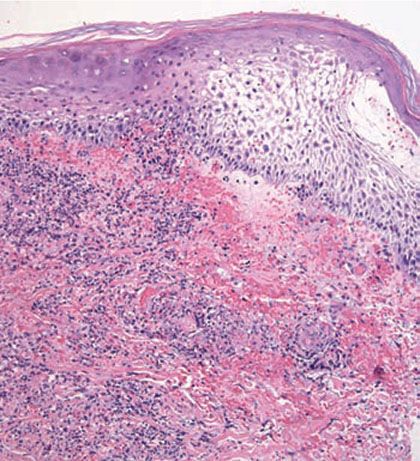

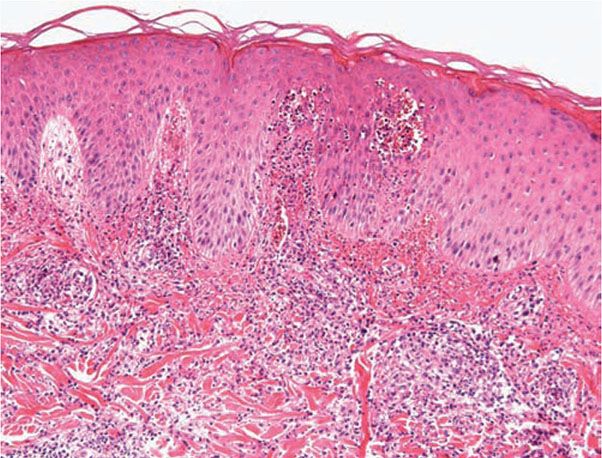

Histopathology. The upper part of the epidermis shows pallor due to intracellular edema and is surmounted by a confluent, thick, parakeratotic scale that may contain neutrophils. There is granular cell layer diminution and focal dyskeratosis. As with necrolytic migratory erythema, there may be architectural disarray and dysmaturation. Subcorneal vesicles may be present. The epidermis manifests variable psoriasiform hyperplasia and atrophy and, in a few instances, acantholysis (58,61). Superinfection with Candida may occur (Fig. 16-2).

Figure 16-2 Acrodermatitis enteropathica. The epidermis demonstrates psoriasiform hyperplasia, dysmaturation, granular cell layer diminution, and vacuolar change. The epidermis is surmounted by a compact parakeratotic scale. Vascular ectasia is also present.

Pathogenesis. Defective intestinal absorption of zinc has been demonstrated in children with acrodermatitis enteropathica (64), resulting in plasma zinc levels well below the normal range of 68 to 112 μg/dL. Oral administration of zinc sulfate results in rapid and complete resolution of the disease. Electron microscopy shows abnormal keratinization with decreased keratohyalin granules and increased number of keratinosome-derived lamellae within intercellular spaces. Keratinosomes contain several zinc-dependent enzyme systems, the metabolism of which may be affected (65).

Congenital zinc deficiency leading to acrodermatitis enteropathica shortly after birth has been linked to a novel mutation in the SLC39A4 gene, localized to chromosome region 8q24.3 (66). The SLC39A4 gene is expressed in tissues involved in zinc absorption, including the stomach, small intestine, colon, and kidney; a mutation alters the protein’s function of zinc absorption, causing zinc deficiency (67). A recent case report described a 13-year-old adolescent girl with acrodermatitis enteropathica who was resistant to high-dose zinc sulfate therapy and was successfully treated with zinc gluconate and vitamin C. The authors detected a novel homozygous c.541_551dup (p.Leu186fsX38) mutation in the exon 3 of her SLC39A4 gene (68).

Differential Diagnosis. Pellagra, necrolytic migratory erythema, and acrodermatitis enteropathica share a constellation of histologic features that should suggest a diagnosis of nutritional dermatosis, namely, confluent parakeratosis, granular layer diminution, epidermal pallor and focal superficial dyskeratosis, superficial epidermal pallor, psoriasiform hyperplasia alternating with attenuation, and architectural disarray and dysmaturation of epidermal keratinocytes, the latter sometimes imparting an appearance mimicking keratinocytic dysplasia. Such cases can be misdiagnosed as eczema and psoriasis.

Principles of Management. Patients usually respond to dietary or parenteral zinc supplementation.

Kwashiorkor

Kwashiorkor is a form of protein malnutrition coupled to carbohydrate excess resulting in the reduction of a patient’s weight by 20% to 40%.

Clinical Summary. The condition is not limited to third-world countries, and risk factors include, in addition to drought and famine, conditions that interfere with protein absorption such as cystic fibrosis, dietary changes for management of food allergies, low-protein diets, including vegan or other restricted diets, infections, parasites, lack of education, and prolonged substandard living conditions. Patients with kwashiorkor may also have other deficiencies, including zinc and vitamin deficiencies (69).

Primary manifestations include generalized hypopigmentation that begins circumorally and in the pretibial regions. With disease progression, hyperpigmented plaques with a waxy texture develop over the elbows and ankles and in the intertriginous areas. Dryness, desquamation, and decreased skin elasticity occur. “Crazy pavement” or “flaky-paint dermatosis” describes the extensive desquamation with erosions and fissuring, vesicles, and bullae that may be seen in severe cases (70). Prominent edema can mask the underlying muscle and subcutaneous tissue atrophy (71). Hair abnormalities include a diffuse alopecia, alternating bands of normal and hypopigmented hair referred to as the “flag” sign, and an unusual reddish-brown discoloration called hypochromotrichia (69). Extracutaneous manifestations include cerebral atrophy secondary to loss of myelin lipid (72), diarrhea, hepatic steatosis, and mucosal abnormalities such as a smooth tongue, angular stomatitis, and perianal and nasal erosions.

Histopathology. The histologic picture of skin lesions is not diagnostic but is said to resemble that of pellagra (29). The changes include psoriasiform hyperplasia with hyperkeratosis and increased pigmentation throughout the epidermis or atrophy with irregular shortening and flattening of the rete (72).

Pathogenesis. The etiology of the edema includes reduced capillary blood flow, hypoalbuminemia, and increased peripheral vasoconstriction (73).

Principles of Management. Correction of dietary protein deficiency should result in amelioration of symptoms.

CUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS OF GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT DISEASE

Pyoderma Gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a condition of poorly understood etiology and pathogenesis in which tissue necrosis results in deep ulcers, often on the legs.

Clinical Summary. First described in 1930 (74), pyoderma gangrenosum was once considered pathognomonic of idiopathic ulcerative colitis but has since been described in association with a wide variety of disorders, including roughly 5% of patients with Crohn disease. Beginning as folliculocentric pustules or fluctuant nodules, the lesions ulcerate and have sharply circumscribed violaceous, raised edges in which necrotic pustules may be seen. The disease most commonly occurs on the lower extremities and trunk in adults who are 30 to 50 years old. Occasionally it occurs in childhood, affecting the buttocks, perineal region, and head and neck area (75,76). Pathergy (development of new lesions) may occur at sites of trauma, including intravenous puncture sites, surgical wounds, and peristomal sites (77). When one examines the various etiologies for lower-extremity ulcers, the vast majority are related to venous and arterial insufficiency (>75%), with pyoderma gangrenosum defining the etiologic basis in only 3% of cases (78). Pyoderma gangrenosum is a diagnosis of exclusion, and many instances exist of incorrect diagnoses of pyoderma gangrenosum being reclassified after thorough investigation. Roughly 70% of cases are associated with inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic disorders, including acute lymphoid and myeloid leukemias and myeloma (particularly immunoglobulin [Ig] A paraprotein disease), rheumatologic conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus, and hepatopathies (79,80), including chronic active hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and sclerosing cholangitis (75,81). Both a superficial granulomatous variant (82) and a vesiculopustular variant comprising disseminated vesicles and necrotizing pustules, some follicular based, have been observed without accompanying systemic disease. The vesiculopustular variant has also been seen in association with ulcerative colitis and/or underlying liver disease (80,83). Pyoderma gangrenosum has been associated with the administration of drugs, including interferon (IFN)-α in the setting of chronic granulocytic leukemia, the antipsychotic agent sulpride (84), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (85), the epidermal growth factor–tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib (Iressa) (86), the retinoid isotretinoin (87), and the thionamide propylthiouracil (88). A recent case described the development of pyoderma gangrenosum at the site of IFN-a2B injections. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor therapy has recently been associated with the development of pyoderma gangrenosum. Since the introduction of TNF-α inhibitors, there is a growing body of literature on the development of various autoimmune sequelae in association with their use (89).

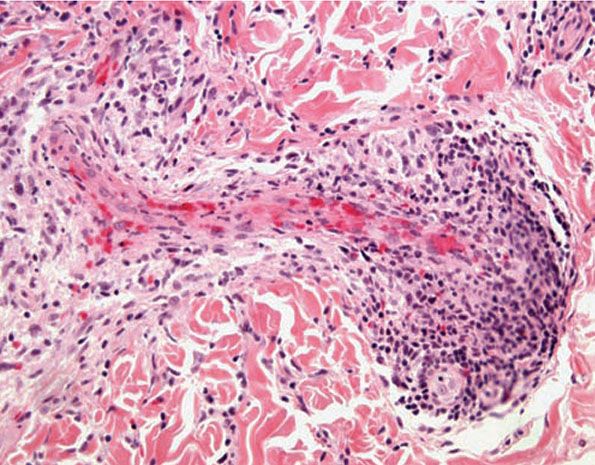

Histopathology. Pyoderma gangrenosum exhibits a dichotomous tissue reaction, showing central necrotizing suppurative inflammation, usually with ulceration, and a peripheral lymphocytic vascular reaction comprising perivascular and intramural lymphocytic infiltrates, usually without fibrin deposition or mural necrosis (Figs. 16-3 and 16-4). Transitional areas show neutrophils in a loose cuff around the angiocentric lymphocytic infiltrates, defining a mixed lymphocytic and neutrophilic vascular reaction termed a Sweet’s-like vascular reaction (90,91). Bullous lesions may also demonstrate a Sweet’s-like vascular reaction with perivascular disintegrating neutrophilic infiltrates and hemorrhage without mural necrosis or luminal fibrin deposition. At variance with Sweet syndrome is the destruction of the connective tissue framework with resultant tissue pathergy (92,93). Although a leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be observed in areas of maximal tissue pathology, pyoderma gangrenosum does not reflect a primary vasculitis (75). In some cases, a necrotizing pustular follicular reaction may be the central nidus of the lesion, particularly in the vesicular–pustular variant associated with ulcerative colitis or hepatobiliary disease. In the superficial granulomatous variant, florid pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may be observed along with the intraepithelial and superficial dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation with admixed plasma cells and eosinophils (80). Cases of pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn disease may have areas of granulomatous inflammation (94).

Figure 16-3 Pyoderma gangrenosum. The center of the lesion shows a neutrophilic infiltrate with leukocytoclasia and dermolysis. This biopsy is from a patient with Crohn disease, as evidenced by the presence of multinucleated histiocytes within the infiltrate.

Figure 16-4 Pyoderma gangrenosum. The undermined epidermis often shows spongiosis or pustulation.

Differential Diagnosis. Tissue neutrophilia with epithelial undermining and ulceration in the absence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, fungal, bacterial, or mycobacterial organisms (which, if indicated, may be demonstrable with culture and special stains, e.g., periodic acid–Schiff, Gomori methenamine silver, Brown and Brenn, Gram’s, Ziehl–Neelson, and auramine-rhodamine preparations) strongly implicates pyoderma gangrenosum when seen in the appropriate clinical setting (75). An incipient lesion of pyoderma gangrenosum, however, may be indistinguishable from Sweet syndrome, although the latter is rarely folliculocentric and does not show lysis of dermal collagen or vessel wall necrosis in areas of maximum dermal neutrophilia. In addition, clinical features usually make the distinction possible. Because of prominent follicular involvement, the differential diagnosis should also include other causes of necrotizing pustular follicular reactions with an accompanying vasculopathy, such as mixed cryoglobulinemia, Behçet disease, rheumatoid vasculitis, herpetic folliculitis, acute pustular bacterid, and pustular drug reactions (95). These other conditions frequently have a necrotizing mononuclear cell- or neutrophil-predominant vasculitis in contrast to the nonnecrotizing vascular reaction of pyoderma gangrenosum. Other causes of a Sweet’s-like vascular reaction include the bowel arthritis dermatosis syndrome, Behçet disease, idiopathic pustular vasculitis, rheumatoid arthritis, acute pustular bacterid, and Sweet syndrome (89,90).

Pathogenesis. Direct immunofluorescence testing supports a vasculopathy by virtue of perivascular deposition of immunoreactants, mainly IgM and C3 (96), in more than half of patients. This change occurs in nonspecific vessel injury and does not support a humoral-based pathogenesis. Defective cell-mediated immunity without humoral abnormalities has been implicated in some patients (97). Immunoelectrophoresis has revealed a monoclonal gammopathy, most commonly of the IgA type, in 10% of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum (98). A recent polymerase chain reaction analysis demonstrated that patients with pyoderma gangrenosum have clonal expansions of T cells in the peripheral blood and skin. These clonal expansions are shared between both sites, suggesting that T cells are trafficking to the skin under the influence of an antigenic stimulus (99). In further support of a potential antigenic stimulus, patients with pyoderma gangrenosum have elevated levels of interleukin 8 (IL-8), a powerful neutrophilic chemoattractant, in both the serum and fibroblasts of affected skin (100).

Principles of Management. Identification and treatment of the underlying disease that is causally associated is important, particularly with respect to the potentially life-threatening malignancies and inflammatory bowel disease. Adequate treatment requires a multimodality approach: systemic anti-inflammatory drugs to stop the inflammation, and localized wound therapy to aid in healing and prevent secondary infection. As regards the treatment of the skin condition, specific wound care guidelines exist (101,102). A multidisciplinary approach with close involvement of wound-care and infectious disease specialists is advised. Treatment includes avoidance of trauma, local application of appropriate topical medications (which may include anti-inflammatory treatments, such as steroids and tacrolimus, or topical antibiotics when indicated [101]), and the use of systemic steroids, cyclosporine, or infliximab for disseminated disease. Other options include mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, dapsone, or alternate treatments (103). Pyoderma gangrenosum is a challenging diagnosis and a diagnosis of exclusion; patients failing to respond to appropriate treatment warrant additional investigation and evaluation.

Bowel-Associated Dermatosis–Arthritis Syndrome (Bowel Bypass Syndrome)

Bowel-associated dermatosis–arthritis syndrome, also called bowel bypass syndrome, was first described as a complication of jejunoileal bypass surgery, and is also seen in patients with diverse bowel-related disorders, including diverticulosis, peptic ulcer disease, and idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. The syndrome includes fever and malaise, polyarthralgia, myalgia, and skin changes.

Clinical Summary. After intestinal bypass surgery for morbid obesity or after extensive small bowel resection, some patients develop an intermittent eruption, mainly on the extremities, comprising purpuric macules and papules that may evolve into necrotizing vesiculopustular lesions. Polyarthritis, malaise, and fever are often associated with, and may precede, the eruption (104). Although originally called the bowel bypass syndrome, it now bears the more appropriate appellation bowel arthritis dermatosis syndrome because a similar picture may develop in patients with other bowel-related disorders (105–108).

Histopathology. Characteristically, there is a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with a peripheral cuff of disintegrating neutrophils, erythrocyte extravasation, and absent or minimal fibrin deposition consistent with a Sweet’s-like vascular reaction; a leukocytoclastic vasculitis occurs less often (107). Papillary dermal edema may be striking and may lead to subepidermal vesiculation (100). Epidermal pustulation, variable epithelial necrosis, and massive superficial dermal neutrophilia complete the picture (Fig. 16-5) and define pustular vasculitis (100,109). In some instances, the primary pathology closely resembles bullous impetigo and/or IgA pemphigus characterized by a subcorneal pustule without the characteristic angiocentric dermal changes (110).

Figure 16-5 Bowel arthritis dermatosis syndrome. Pustular vasculitis characterized by dermal papillae microabscess formation along with a leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Pathogenesis. Circulating immune complexes, including those containing cryoproteins, are demonstrable in most patients. The antigenic trigger may be peptidoglycans from overgrowth of intestinal bacteria (104), which are structurally and antigenically similar to the peptidoglycan of Streptococcus. The latter exacerbate symptoms in patients with this condition and produce a similar syndrome in animals (104). Direct immunofluorescence testing has shown linear and granular deposits of immunoglobulins and complement along the dermal–epidermal junction and within vessels (104). One study showed Escherichia coli antigens in a granular array along the dermal–epidermal junction. Via an indirect methodology, a pemphigus-like pattern of intercellular staining has been reported (104), the significance of which is unclear.

Differential Diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of bowel arthritis dermatosis syndrome includes Sweet syndrome, incipient pyoderma gangrenosum, and certain of the pustular vasculitides, such as acute pustular bacterid related to antecedent streptococcal infection, such as Henoch–Schönlein purpura (108), septic vasculitis due to Meningococcus and Gonococcus, Behçet syndrome, leukocytoclastic vasculitis in patients with a pustular psoriasiform diathesis (111), idiopathic pustular vasculitis, and acute generalized exanthemous pustulosis (90,110). The distinction may be impossible in those conditions that manifest a Sweet’s-like vascular reaction (90)—namely, Behçet disease, Sweet syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, acute pustular bacterid, and idiopathic pustular vasculitis, and rheumatoid arthritis-associated neutrophilic eruptions.

Principles of Management. Once a correct diagnosis is made, a combination of steroid therapy, antibiotics, and dietary probiotics may offer empirical relief. There is no good randomized, blinded, controlled trial to generate a specific evidence-based therapeutic algorithm, however.

SPECIFIC DISEASES

Aphthosis (Behçet Disease)

Behçet disease is a symptom complex of oral and genital ulceration and iritis that has a worldwide distribution but is most common in the Pacific Rim and Eastern Mediterranean (112,113).

Clinical Summary. The presence of oral ulceration plus any two signs of genital ulceration, skin lesions (e.g., pustules or nodules), or eye lesions (e.g., uveitis or retinal vasculitis) is diagnostic. There are some patients who have complex aphthosis without the other clinical features of Behçet disease. The majority of these patients have the so-called idiopathic recurrent oral and/or genital aphthosis, while approximately one-quarter of these patients will have an underlying inflammatory bowel disease (114).

The cutaneous lesions include erythema nodosum–like nodules, vesicles, pustules, pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet syndrome, a pustular reaction to needle trauma, superficial migratory thrombophlebitis, ulceration, infiltrative erythema, acral purpuric papulonodular lesions, and acneiform folliculitis or pseudofolliculitis (115,116).

The extracutaneous manifestations are categorized as oral and/or genital aphthae; vasculo-, ocular-, entero-, or neuro-Behçet disease; renal disease; and arthritis. Oral apthosis recurring at least three times over a 12-month period is essential to the diagnosis (105). In vasculo-Behçet disease, aneurysms and occlusive venous and arterial main-vessel lesions occur. The ocular manifestations include uveitis, hypopyon iritis, optic neuritis, and choroiditis. Entero-Behçet disease manifests as diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, vomiting, and melena. Neuro-Behçet disease presents as brainstem dysfunction, meningoencephalitis, organic psychiatric symptoms, and mononeuritis multiplex (114). Asymptomatic microhematuria and/or proteinuria are among the renal manifestations. An oligoarthritis may involve the wrist, elbow, knee, or ankle joints. Morbidity and mortality in one large series of Turkish patients were greatest in young males; both the onset and the severity of ocular disease were greatest early in the course of disease, suggesting that the “disease burden” in Behçet disease is greatest early and that it tends to “burn out” over time (117). However, neurologic and major vessel disease can occur at any time and can have a late onset 5 to 10 years into the course of illness (116). Hypercoaguability and deep-vein thromboses are not uncommon.

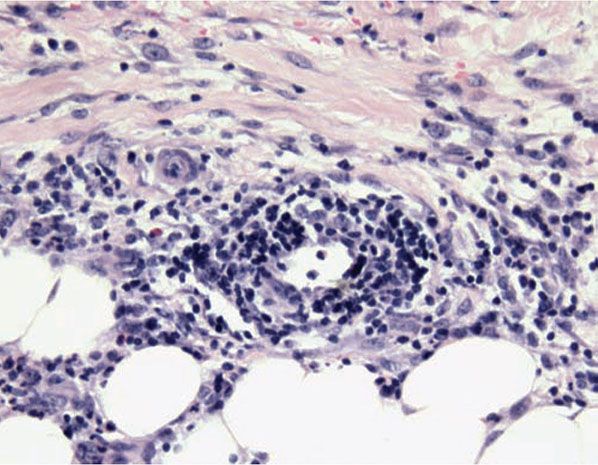

Histopathology. The cutaneous lesions can be categorized histopathologically into two main groups: vascular and extravascular with or without vasculopathy including acneiform.

The pathologic spectrum of the cutaneous vasculopathy encompasses a mononuclear cell vasculitis with variable mural and luminal fibrin deposition; a paucicellular thrombogenic vasculopathy (Fig. 16-6); and a neutrophilic vascular reaction involving capillaries and veins of all calibers. The mononuclear cell reaction may be frankly granulomatous or it may be lymphocyte predominant to define a lymphocytic vasculitis. The neutrophilic vascular reaction may resemble that of Sweet syndrome (Fig. 16-7) (118) or a leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Diffuse extravascular mononuclear cell– and/or neutrophil-predominant inflammation of the dermis and/or panniculus may occur with or without the aforementioned vascular changes. The histiocytes infiltrating the panniculus may manifest phagocytosis of cellular debris. Suppurative or mixed suppurative and granulomatous folliculitis with or without vasculitis characterizes the acneiform lesions. Acral purpuric papulonodular lesions show a lymphocytic interface dermatitis with lymphocytic exocytosis, dyskeratosis, and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, recapitulating the mucosal histopathology (115).

Figure 16-6 Behçet disease. A characteristic vascular reaction pattern is a lymphocytic thrombogenic vasculopathy.

Figure 16-7 Behçet disease. There is a Sweet’s-like vascular reaction manifested by angiocentric mononuclear cell and neutrophilic infiltrates with erythrocyte extravasation and leukocytoclasia but without accompanying mural and intraluminal fibrin deposition.

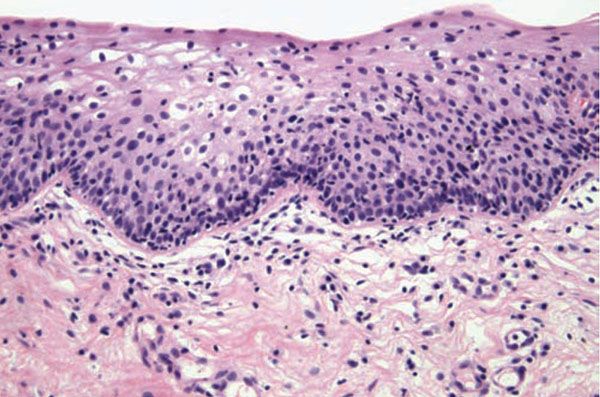

Extracutaneous lesions histologically mirror the skin changes. Oral aphthous ulcers demonstrate a central diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate with necrosis of the epithelium and connective tissue pathergy of the submucosa, and peripherally a border showing dense lymphocytic infiltration with lymphocytic exocytosis and degenerative epithelial changes. Genital aphthae have the same appearance (Fig. 16-8) (114). The large-vessel arteriopathy represents an ischemic sequel of a mononuclear cell vasculitis of the vasa vasorum (119), whereas venous thrombosis may be due in part to an underlying hypercoagulable state. A lymphocytic vascular reaction with or without mural and intraluminal fibrin deposition is the histopathology of neuro-, entero-, ocular-, and arthritic Behçet disease, with other organ changes such as demyelination and intestinal ulceration reflecting resultant ischemia (114). The renal histopathology includes IgA nephropathy, focal and diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis, and amyloidosis (120).

Figure 16-8 Behçet disease. Although the center of an oral or vulvar aphthous ulcer is predominated by a neutrophilic response, biopsies of the periphery typically show a lymphocyte-predominant infiltrate both in an extravascular and angiocentric disposition with variable lymphocytic exocytosis.

Differential Diagnosis. The lymphocytic vasculitis observed in Behçet disease may mimic that seen in association with systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis (121,122), Sjögren syndrome, relapsing polychondritis, Degos disease, and paraneoplastic vasculitis in the setting of lymphoproliferative disease. Granulomatous vasculitis may also be observed in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (allergic granulomatosis of Churg–Strauss), Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, acquired hypogammaglobulinemia, a postherpetic eruption (123), paraneoplastic syndrome (related to underlying hematologic malignancy), rheumatoid arthritis, hypersensitivity reactions to certain infections, including syphilis and tuberculosis (124), scleroderma, and late-stage lesions of microscopic polyarteritis nodosa (90,108,121). Other causes of a Sweet’s-like vasculopathy include Sweet syndrome, bowel arthritis dermatosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and idiopathic pustular vasculitis (89). Conditions that combine a vasculitis with a folliculitis include pyoderma gangrenosum, mixed cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid vasculitis, and bacterid (94).

Pathogenesis. An immunogenetic basis is likely in view of the association with certain HLA types, namely, HLA-B5, HLA-B12, HLA-B27, and HLA-B51 (125). A recurring association in patients of Japanese, Turkish, Korean, and Iranian ethnicities is with HLA-B51 (126,127), genetic polymorphisms in the promoter region of TNF-α (128–131), and microsatellite instabilities between these two genes (118,123,126,132). Polymorphisms of other cytokines have been identified, including IL-1 (133) and IL-18 (134). Patients with Behçet disease have elevated levels of TH1 cytokines IL-12, IFN-γ, and TNF-α (135); increased TH1-associated chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR3 (136); and a lower percentage of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in peripheral blood (137), supporting the proposed TH1-mediated pathogenesis of the disease. Patients have shown a heightened immune response to antigenic components of certain streptococcal species (138,139), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (140), herpes simplex (141,142), Epstein–Barr virus, and HIV (143). The underlying abnormalities in T-lymphocyte function may be integral to an aberrant response related to the synthesis by microorganisms and mammalian tissue of a family of polypeptides termed heat shock proteins (HSPs) (144,145) produced by cells exposed to stresses such as increased temperature. Sensitized T cells and T-cell clones specific to the 65-kD mycobacterial HSP have been reported in rheumatoid arthritis (146). In one study, T lymphocytes from patients with Behçet disease exhibited a greater stimulation by this HSP compared to normal controls or patients with unrelated disease (147). The γδ T-cell subset has been shown to be the principal populace that responds to the mycobacterial 65-kD HSP, an observation that may account for the increase in circulating γδ T cells in patients with antecedent streptococcal or mycobacterial infections (148) and in those with active Behçet disease, in whom an exaggerated response to microbial products in mucosal ulcers is postulated (149). The lymphocytes themselves show resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis, a finding that may promote lymphocyte-mediated tissue destruction in these patients (150). One recent study assessed the phenotypic composition in cutaneous lesions of Behçet disease. The dominant infiltrate in all lesions excluding frankly pustular ones comprised CD68-positive macrophages admixed with lymphocytes showing a predominance of CD8+ T cells over those of the CD4 subset (151).

Tissue neutrophilia may relate to the presence of HLA-B51, which has been associated with neutrophil hyperreactivity (152). Neutrophil functions are also increased in Behçet disease (153), which may be due to alteration in the expression of Toll-like receptors, regulators of innate and adaptive immunity, on both granulocytes and monocytes (154).

Vascular thrombosis has been attributed to antibody-mediated endothelial injury (155), protein C or S deficiency (156), factor XII deficiency, inhibition of plasminogen activator, and circulating lupus anticoagulant (157–159). A prothrombin gene mutation has recently been described (160). Further evidence of a genetic predisposition to thrombosis is the linkage of HLA-B51 expression and the absence of HLA-B35 as risk factors for venous thrombosis in Turkish patients (125); there is also a statistical linkage between superficial and deep venous thrombosis (161). Elevated serum levels of matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 are associated with vasculo-Behçet disease, particularly thrombotic and aneurysmatic involvement, respectively (162).

The role of nitric oxide (NO) is unclear. Some researchers have shown that patients with active Behçet disease have significantly higher serum levels of NO than patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis (163), patients with inactive Behçet disease, and healthy controls (164), whereas others maintain that there is no difference in NO levels among these groups (165,166), and still others contend that levels of NO are lower in patients with Behçet disease (167,168). Specific genetic polymorphisms have been identified in the manganese superoxide dismutase gene in Japanese patients with Behçet disease (169) and the Glu298Asp polymorphism in the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene in Turkish (170,171), Italian (172), and Korean (173) patients with Behçet disease. One study did not identify the eNOS polymorphism in Turkish patients with Behçet disease (174). Others propose that the significantly higher levels of IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, and NO are related to the pathogenesis of Behçet disease (175).

Principles of Management. The main aim of treatment is to prevent irreversible organ damage (176). Most of the serious manifestations respond to immunosuppressive therapy (177), namely, corticosteroids, colchicine, azathioprine, TNF-α inhibitors, and other agents. A questionnaire submitted to participants of the 2010 International Society for Behçet’s Disease meeting indicated that more than half would intensify immunosuppression and also anticoagulate their patients with new-onset deep-vein thromboses (178).

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Crohn Disease (Regional Enteritis)

First described in 1932, Crohn disease is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract.

Clinical Summary. The diagnosis is based on a constellation of radiologic, pathologic, and endoscopic data, namely deep mucosal fissures, fistula formation, transmural inflammation, discontinuous colonic and small bowel disease with preferential right-sided involvement, and sarcoidal granulomatous and fibrosing inflammation of the mucosa and submucosa (179). Extraintestinal manifestations include fever, anemia, lupus anticoagulant, ophthalmic disease such as uveitis and episcleritis, monoarticular large-joint arthritis, polyarthritis, spondylitis, amyloidosis (180), renal lithiasis with resultant hydronephrosis (181), cerebral vascular occlusions, and a spectrum of cutaneous eruptions.

Skin manifestations, principally restricted to patients with colonic disease, occur in 14% to 44% of patients with Crohn disease, depending on whether perianal disease is considered a cutaneous manifestation (175). Ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetant plaques may extend in continuity from sites of intra-abdominal involvement to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, ostomy sites, or incisional scars. When sterile granulomatous skin lesions arise at sites discontinuous from the gastrointestinal tract, the appellation “metastatic Crohn disease” is applied (182). Clinically, metastatic Crohn disease presents as solitary or multiple nodules, plaques, ulcers, lichenoid lesions, or violaceous perifollicular papules involving extremities, intertriginous areas, abdominal skin folds, or genitalia (183). Erythema nodosum (184)—the most common cutaneous manifestation of Crohn disease—and pyoderma gangrenosum develop in 15% and 1.5% of patients, respectively. Palmar erythema, a pustular response to trauma (183), erythema multiforme usually with mucosal involvement (183,185), epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, hidradenitis suppurative, rosacea, secondary cutaneous oxalosis, malabsorption-related acrodermatitis enteropathica (171,183), vasculitic lesions, including benign cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, and digitate hyperkeratosis reminiscent of punctate porokeratosis are described (186). Cutaneous necrosis as a complication of circulating lupus anticoagulant may also occur. A distinct manifestation of Crohn disease is one of scrotal edema. Not surprisingly, granulomatous infiltrates are seen typically showing localization to vascular lumens of the lymphatics, in a fashion mimicking Melkersson–Rosenthal disease (187).

Oral lesions—manifesting as “cobblestone” lesions, aphthous ulcers, lip swelling, and pyostomatitis vegetans—occur in roughly 5% of patients with Crohn disease (170).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree