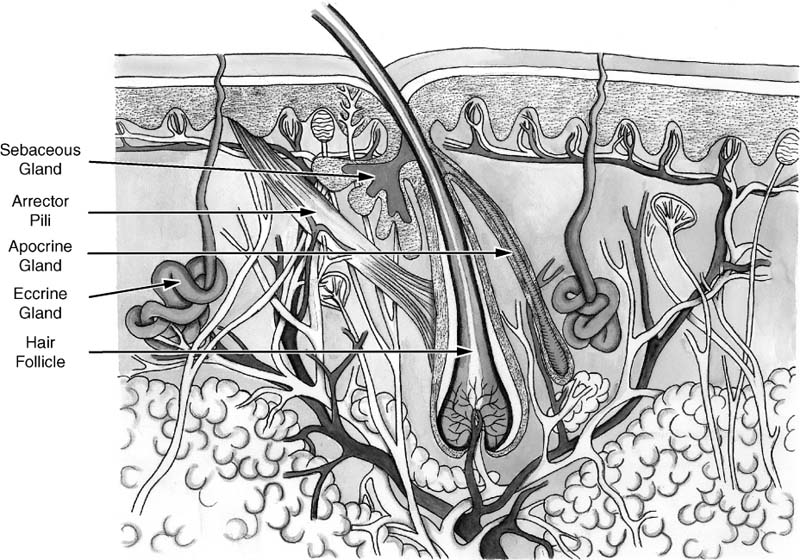

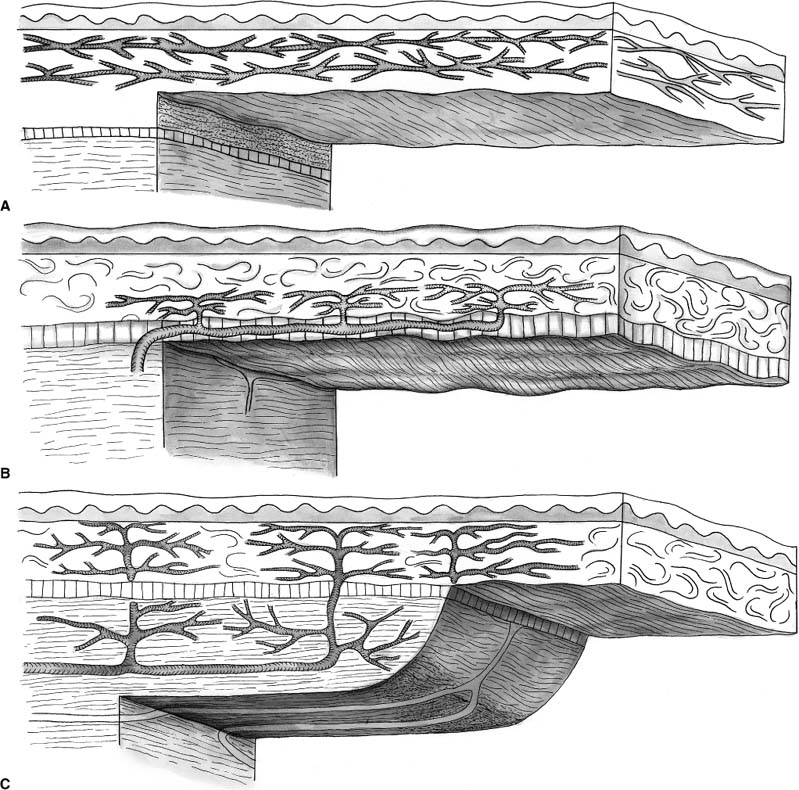

Chapter 2 Cutaneous lesions of the face and neck are ubiquitous in the elderly group and the accurate diagnosis and distinction among those that are benign, premalignant, and malignant remains critical. This chapter reviews the essential features that aid in this evaluation and presents guidelines for their management. The repair of facial cutaneous defects is an intriguing component of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery; a variety of locations and sizes, as well as functional considerations, call for a wide array of surgical techniques that allows one to achieve the optimal outcome. It is often helpful to have a series of essential principles and a practical algorithm for analyzing some of the more challenging defects. This chapter covers the basic techniques for many common local and regional flaps and discusses the special considerations and nuances of each facial unit. This chapter is not a comprehensive surgical atlas but rather an overview of the essential principles. The epidermis is the most superficial layer of cells and functions to protect the deeper tissues and retain moisture. Its capacity to do this is seen clinically when patients suffering from thermal burns are overcome by infection and fluid loss. This layer of skin is divided into, from the deepest layer to the superficial one, the stratum basale, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and stratum corneum. The keratinocytes from the basal layer migrate superficially up to the stratum corneum with an average turnover time of ~30 days. Malignant transformation of this cell type is responsible for the de novo birth of a cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA), the second most common skin cancer after basal cell carcinoma (BCCA). Melanocytes are found in the basal layer of the epidermis and are of neural crest origin. Their production of melanin gives skin its pigmented color and is thought to protect the keratinocytes from the harmful effects of ultraviolet radiation. The numbers of melanocytes do not vary in people of different races; an individual’s skin color is influenced by the relative production of melanin. Albinism is associated with a congenital deficiency of tyrosinase, an essential enzyme for the production of melanin, and it is characterized by pale skin and a great risk for burning and actinic injury. Langerhans’ cells are also within the epidermis and have an important role in the antigenic processing of immunologic responses to the external environment. Beneath the basement membrane, the dermis is divided into the superficial papillary and deeper reticular layers. The dermis contains many essential elements of skin, i.e., fibroblasts, collagen fibers, elastin fibers, ground substance, the neurovascular bundles of skin, the pilosebaceous units (hair follicle and sebaceous gland), arrector pili muscles, eccrine sweat glands, and, in some areas, the apocrine glands (Fig. 2-1). This layer of skin is responsible for many of the external features of skin, such as tone, elasticity, mechanical strength, and wrinkles. Youthful skin is characterized histologically by a well-organized architecture of collagen bundles immediately beneath the basement membrane. These collagen bundles diminish and become more disorganized with time and give rise to the intrinsic wrinkles seen in older individuals. Collagenase is produced by the keratinocyte and accelerates this degradation process. Smoking and actinic injury are thought to increase the production of collagenase, whereas topical tretinoin may inhibit collagenase activity and preserve a more youthful skin tone.1 The pilosebaceous unit consists of the hair bulb, hair follicle, sebaceous gland, arrector pili muscle, and sensory end organs. This important structure produces sebum, retains moisture, regulates temperature, and can stimulate epidermal regeneration. Beneath the dermis, the subcutaneous fat envelops the head and neck and is a distinct layer of variable thickness. The eyelids and skin of the external auditory canal are unique in that they contain little or no subcutaneous fat. The vasculature of facial skin is robust with distinct patterns of perfusion. Within the dermis, there are two vascular arcades, a superficial one between the reticular and papillary dermis and a deeper one often referred to as the “subdermal plexus,” the latter usually being dominant. In some areas, the vascular supply to the skin is directly from a major perforating vessel off a deeper artery in the muscular or fascial plane (Fig. 2-2). A musculocutaneous vessel perforates the underlying muscle, vascularizing the muscle en route to the skin. The direct cutaneous arteries also arise from the deeper larger vessel but travel within fascial slips between muscles to nourish the skin exclusively. Flaps can be defined by their vascular supply, as discussed below. FIGURE 2-1 Skin dermis and hair follicle. Cutaneous malignancies are by far the most common malignancy in humans and fortunately are associated with a favorable prognosis. Eighty percent of these lesions are found on the face and neck, the nose in particular (30%), and the nasal tip subunit specifically2 The forehead and cheeks are also areas of particular risk. There are over a half million new cases in the United States annually, with a lifetime risk of ~33% in Caucasian Americans.2–4 Among individuals with a history of a skin cancer, the risk of a second neoplasm increases dramatically to roughly 50% within 5 years and speaks to the need for diligent follow-up.5,6 Exposure to the sun and harsh environment is by far the greatest risk for the development of cutaneous malignancies; thus outdoor occupations and living closer to the equator or at higher altitudes are demographic risk factors. Ultraviolet (UV) rays are defined by their wavelength and categorized as UVA, UVB, or UVC. UVA rays are primarily responsible for melanocytic stimulation and tanning. UVB rays (290-320 nm) cause the greatest DNA injury and are most responsible for the neoplastic degeneration of epidermal cells (“B” for “bad”). Radiation from the UVC spectrum is mostly absorbed by the ozone stratosphere and has little impact on skin injury. Short bursts of intense sun at an early age appear to be more damaging than long-term, low-dose exposure; a child with recurrent sunburns may be at greatest risk for future skin malignancies. In addition to the volume of sun exposure, several other variables are associated with an increased risk for cutaneous malignancies. Genetic and ethnic influences can predispose individuals to skin lesions, particularly individuals from Northern European or of Celtic origin (Fitzpatrick skin types I and II). Basal cell nevus syndrome is a genetic syndrome afflicting younger people and is characterized by multiple BCCAs reoccurring throughout the body7 It is also associated with bifid ribs, frontal bossing, and mandibular cysts. Dysplastic nevus syndrome is a familial disease where a large number of irregular nevi continue to form throughout life and is associated with a risk of malignant melanoma. Very close observation with serial photographic documentation is imperative for prompt diagnosis and treatment of this malignant disease. Xeroderma pigmentosa is an autosomal-recessive disorder associated with improper DNA repair leading to extreme actinic sensitivity and multiple cutaneous malignancies. Bowen’s disease is characterized by diffuse areas of erythematous and scaly plaques that show full-thickness epithelial dysplasia or SCCA in situ. Although the disease is superficial and does not violate the basement membrane, the involved regions warrant close monitoring and conservative treatment due to the risk of malignant degeneration. FIGURE 2-2 Blood supply to the skin. (A) Subdermal plexus used in random donor flaps. (B) Fascial cutaneous pattern using a single, axial vessel within the fascial plane over the muscle. (C) Musculocutaneous pattern is based on perforators from deep muscular arteries. Low-dose ionizing radiation was a common practice years ago for the management of acne or adenotonsillar hypertrophy. Long-term effects of this superficial radiation have been implicated for carcinogenesis. Immunosuppression from a systemic illness, be it neoplasm, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or allograft transplantation, is also associated with an increased risk of multiple cutaneous malignancies.8 Areas subject to chronic inflammation such as infected sinus tracts, nonhealing ulcers, and old scars from burns show a predilection for neoplastic degeneration.7,9 Prolonged exposure to chemicals such as arsenic and hydrocarbons also appears to be a risk factor for cutaneous malignancies.6,10 The diagnosis of a cutaneous lesion is occasionally obvious from clinical inspection alone, but at other times it remains elusive, even to the trained eye. In general, lesions tend to be representative of their cell of origin. Tumors arising from the epidermal layer present as superficial growths that are often scaling. Deeper lesions, on the other hand, tend to push up the epidermal layer and present as more nodular growths with normal-appearing surfaces. Clinical presentations have a tremendous overlap, and the definitive diagnosis comes with biopsy and histologic examination, at times with special stains. There are several different biopsy techniques available but they share a common goal of obtaining sufficient tissue for diagnosis while minimizing morbidity, patient discomfort, and subsequent inflammation that might hinder the examination of specimen margins. Shave biopsy is one of the most common and effective techniques and has two distinct advantages: (1) the biopsy site heals rapidly with local wound care alone, and (2) the deeper tissues are left undisturbed without inciting an inflammatory host reaction. The latter issue becomes important when definitive excision is being performed. Surrounding host inflammation is often suggestive of adjacent tumor invasion and can be misleading when this is found along the deep margin of the specimen. The biopsy itself incites some surrounding inflammation. The shave biopsy should be performed to the mid-dermis level to make an accurate diagnosis (Fig. 2-3). It should not be performed, however, on a pigmented lesion where a malignant melanoma is possible because the depth of invasion is paramount in defining treatment and prognosis. A punch biopsy is equally rapid and dependable, giving a sufficient amount of tissue for analysis of tumor depth. The wound can be closed with a single stitch and heals well. Disposable punch instruments vary in size and a 2- to 4-mm diameter is adequate. By applying traction to the skin perpendicular to the skin tension lines prior to the punch excision, the resultant defect assumes an elliptical shape and assists with closure along those lines. Incisional biopsy is utilized for larger tumors or in anatomically sensitive areas such as around the eyes or nose. It is best to sample the margin of the lesion, capturing a small amount of surrounding normal skin and avoiding areas of central necrosis. For pigmented lesions, it is imperative to biopsy full-thickness skin, into subcutaneous tissue, to determine lesion depth. Excisional biopsy is useful when the clinical suspicion is low and the lesion is small enough to permit a single-stage treatment. FIGURE 2-3 Shave biopsy of a cutaneous lesion. Biopsy is taken down to the reticular dermis. While selecting the definitive treatment, it is important to bear in mind that a disproportion of recurrent lesions (90%) occur on the face and neck rather than other regions of the body11 One implication of this is that primary malignancies of the face are being inadequately treated initially, perhaps due to aesthetic concerns. Furthermore, recognizing that recurrent lesions are often more aggressive and difficult to control, every effort should be made to ensure complete eradication initially, especially during direct excision and primary repair. Application of topical 5-fluorouracil (Effudex, ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Costa Mesa, CA) blocks DNA synthesis in dividing cells and is an effective means of treating scattered lesions, especially multiple, premalignant actinic keratoses. Moderate erythema and desquamation are expected for several days following treatment. Chemical penetration is minimal beyond the epidermis and thus not indicated for deeper lesions. Deep chemical peels, dermabrasion, and laser resurfacing are other methods of resurfacing that are occasionally used for diffuse and superficial skin lesions. Isolated premalignant lesions and well-defined superficial cancers can be managed conservatively with cryotherapy. This technique freezes the lesion through application of a cryogen such as liquid nitrogen, which drops the skin temperature to -50°C. As intracellular ice crystals form and later thaw, local tissue destruction occurs and tumor cell death results. This cycle can be repeated for additional tissue destruction. The treated area develops some erythema, exudate, and occasionally a small bulla, but the final cosmetic outcome is generally excellent. When used appropriately, the cure rates for this technique approach 95% and have the advantage of being simple, safe, and inexpensive.12,13 Curettage and desiccation (C&D) may be the most widely practiced method of treatment for skin cancers.14 Like cryotherapy, it is indicated for smaller, well-defined, nonmelanoma skin cancers and is characterized as being simple and inexpensive and having acceptable cure rates.2,7 The technique involved a vigorous scraping of the lesion with a hand-held curette followed by electro-desiccation of the wound base. The process can be repeated for two to three cycles. The resultant defect is allowed to heal by second-intention. There are two disadvantages to C&D: (1) there is no specimen from the procedure for analysis, and (2) the defect is usually a small crater that leaves a contour irregularity and patch of hypopigmented scar. More complex cutaneous lesions are usually treated definitively with direct surgical excision. When the diagnosis is suspected and the lesion relatively small, one can plan an excisional biopsy with close margins. Clinical margin for surgical excision of a known BCCA should be about 2 to 3 mm, 4 to 5 mm for a SCCA, and 10 mm for a melanoma (Table 2-1). Standard excision has the advantages of being relatively direct, providing a permanent specimen, leaving a favorable cosmetic repair, and having cure rates that approach 95%.2,15 It is essential to bear in mind, however, that traditional pathologic sectioning reviews less than 2% of the surface area of the specimen margin, allowing nests of tumor to penetrate and remain undetected. When the clinical margin is more ambiguous, even frozen section control does not adequately assess tumor margin and the risk of recurrence rises dramatically15 When a positive specimen margin is identified, the risk for recurrence is roughly 33% and reexcision is indicated.16,17 It is interesting to note that the recurrence is not 100%, implying the ability for a host to successfully combat the remaining tumor cells. Alternatively, one is forced to take a larger margin from an area where maximal tissue preservation may be imperative. The importance of proper selection of lesions to be treated with simple excision cannot be overemphasized.

CUTANEOUS LESIONS AND FACIAL RECONSTRUCTION

CUTANEOUS ANATOMY OF THE FACE

CUTANEOUS LESIONS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

RISK FACTORS FOR SKIN LESIONS

BIOPSY TECHNIQUES

TREATMENT OPTIONS

| Type of Cancer | Margin (mm) |

|---|---|

| Nodular BCCA | 2-3 |

| Morpheaform BCCA | 4-5 |

| SCCA | 4-5 |

| Lentigo maligna (melanoma in situ) | 5 |

| Malignant melanoma | 10-15 |

BCCA, basal cell carcinoma; SCCA, squamous cell carcinoma.

Mohs’ micrographic surgery was first described by Frederic E. Mohs while he was a medical student at the University of Minnesota in the early 1940s. Although some of the technical aspects have changed, the principles have revolutionized the contemporary management of skin cancers and have defined the gold standard for treatment, reaching cure rates of 99%. Even challenging tumors such as poorly defined SCCAs or infiltrating BCCAs can be cured in ~95% of cases, in contrast to 75 to 90% by other techniques.18,19 Mohs’ surgery requires careful mapping of the entire margin of a cutaneous lesion, including the deep surface, followed by frozen-section analysis. Based on these histologic readings, the lesion is serially excised to ensure complete extirpation of tumor while maximizing preservation of uninvolved skin. Indications for Mohs’ surgery are influenced by physicians’ preferences, but general considerations include recurrent malignancies, lesions in fusion planes where subclinical extension is likely, lesions arising in areas where tissue preservation is critical, such as the eyelid or nose, ill-defined lesions such as most SCCAs and some BCCAs (infiltrating, morpheaform, or keratotic), large tumors (>2 cm on the face), or tumors arising within scars or irradiated skin (Table 2-2). Melanomas are not efficiently managed by Mohs’ surgery because malignant melanocytes are difficult to detect by frozen-section methods and skip lesions occur frequently and would remain undetected. For this reason, larger margins are used during definitive excision for pigmented cutaneous malignancies (discussed below).

| Limited surrounding skin |

| Ill-defined borders |

| Recurrent tumor |

| Tumors within scars or irradiated tissues |

| Aggressive BCCA subtype |

| Morpheaform |

| Sclerosing |

| Infiltrating |

| Micronodular |

| SCCA, poorly differentiated |

| Perineural invasion |

Radiation therapy has been used for many decades as a treatment modality for cutaneous malignancies, but its use declined recently due to the advances in surgical techniques, both for excision and reconstruction. Nevertheless, it remains an effective and noninvasive means of treatment with cure rates for primary neoplasms approaching 90%.7,20 The most frequent clinical scenarios in which external radiation is selected include positive margins, perineural invasion, palliative treatment, and poor surgical candidates. Cure rates for primary lesions correlate directly with tumor size; lesions greater than 2 cm have a poorer control rate and are seldom used primarily. Disadvantages of radiation include treatment duration (4-6 weeks), local skin irritation, erythema, atrophy, hair loss, telangiectasia, and hypopigmentation, some of which can be cosmetically problematic. Repeated courses of treatment are rarely tolerated and, because multiple and recurrent lesions in this patient group are the rule rather than the exception, one must recognize that potential future modalities are being exhausted.

There are other less conventional treatment modalities that are currently being investigated. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) involves the topical application of a chemical (aminolevulinic acid), which is then absorbed and metabolized by the tumor cells into a photosensitizing porphyrin. The lesion is then exposed to high-energy light and the photoporphyrins generate a cell toxin and lead to tumor death.21 PDT appears successful for superficial skin lesions with cure rates around 90%; however, larger, more aggressive tumors do not respond as well. Intralesional injection of interferon-a may have a tumoricidal effect by promoting the cytotoxicity of natural T cells.22–24 Host immune response may have an important role in tumor surveillance. Retinoids are a derivative of vitamin A that influences cell growth and their beneficial effects on actinic keratoses have been shown.25 Systemic, high-dose retinoids have a beneficial effect in terms of controlling skin tumors in immunosuppressed patients as well as those with xeroderma pigmentosum and basal cell nevus syndrome.26,27 Its role in the prevention of cutaneous malignancies among people at high risk remains to be defined.

Nonpigmented Benign Neoplasms

Warts

Verruca vulgaris, the common wart, is a common epidermal neoplasm caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV) and usually presents as a small (1-2 mm) nodule or occasionally a flat (verruca plana) or filiform lesion with a narrow pedicle. It usually occurs in children and can be self-limited. Histologically, there are benign, hyperkeratotic epithelial cells. Molluscum contagiosum is a variant related to the pox viral family and appears as multiple, small, waxy, dome-shaped lesions scattered over a facial unit. The treatment for warts is usually sharp excision or cryotherapy but recurrence is the rule with inadequate management, especially at the base of the lesion. Curettage or laser ablation are alternative methods that can be successful. Fortunately, most viral lesions are self-limited, and they involute from the host’s immune response.

Seborrheic Keratoses

Seborrheic keratoses are benign skin lesions that are common in adults, especially in those with a history of sun exposure. The lesions are typically brown, well demarcated, soft to touch, and slightly raised. On occasion they are verrucous and have a keratotic plug. The color tends to be uniform but there can be enough variability to resemble a melanotic growth. Histologically, the neoplasm is limited to a superficial hyperkeratosis and acanthosis without deep extension. Because there is no malignant potential, no intervention is mandatory; however, excellent cosmetic treatment can be accomplished with sharp excision using a shave technique, cutting the lesion flush with the surrounding epidermal layer. Cryotherapy is an effective alternative. Although the lesions themselves are benign, a “shower” of seborrheic keratosis may suggest internal malignancies, particularly adenocarcinoma of the colon (Leser-Trelat sign).

Actinic Keratoses

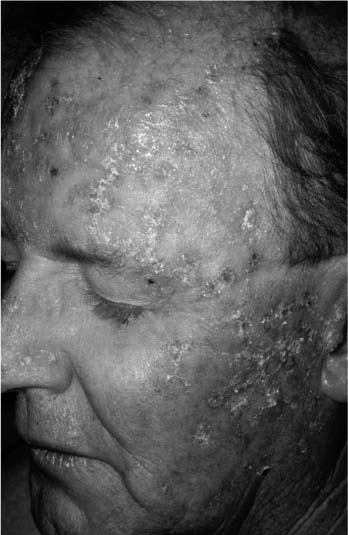

Actinic keratoses are premalignant lesions commonly found on all sun-exposed areas of skin, especially in the elderly. They typically appear as small, scaly, and flat lesions with irregular borders and an erythematous base. Patients often feel the rough lesion before a visible, demarcated growth is seen. Most lesions occur at multiple sites and are more common in people with fair skin (Fig. 2-4). Histologically, one finds cellular atypia within the epidermal layer but without clear malignant features. When they arise on the lips, especially the lower, they are known as actinic cheilitis (Fig. 2-5). The risk of these lesions evolving into a cutaneous malignancy, both SCCA and BCCA, is 10 to 20% over a lifetime.

FIGURE 2-4 Actinic keratoses with multiple, scaly lesions with an erythematous base. (See Color Plate 2-4.)

FIGURE 2-5 Actinic cheilitis. (See Color Plate 2-5.)

Actinic keratoses require definitive treatment due to their known malignant risk. Isolated lesions can be addressed with shave excision or cryotherapy. Because they often occur in large numbers, surgical excision may not be practical and diffuse topical treatments are often needed. Topical 5-fluorouracil is effective and frequently applied to large facial units, creating a posttreatment erythema and irritation that patients must be forewarned about.

Keratoacanthoma

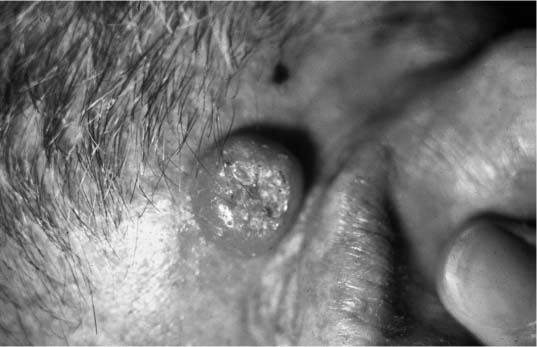

Keratoacanthoma (KA) is an epithelial neoplasm usually occurring as a solitary lesion on sun-exposed surfaces of the elderly. These solitary lesions are characterized by rapid growth and were originally assumed to be malignant. Closer inspection, however, has revealed that these lesions are often clinically and histologically distinct from SCCA. Most importantly, they are characterized by three unique clinical phases: rapid growth, plateau, and involution. Typically, the lesions reach full size in 2 months, and they then begin involution by the sixth month. Grossly, they appear as a dome with central keratin plug, usually reaching 1 to 2 cm before stabilizing (Fig. 2-6). Histologically, there are only benign epithelial cells with pushing borders and no violation of the basement membrane.

FIGURE 2-6 Keratoacanthoma. Raised nodular lesion with central, keratotic plug. (See Color Plate 2-6.)

There are variations from the typical KA. The giant KA can reach greater than 5 cm and cause permanent destruction to underlying tissues before involution commences. Multiple lesions can also arise and appear to be a different form of this disease, occurring in younger patients and occasionally on palms and soles.

The treatment of KA is controversial due to the spontaneous involution that characterizes this lesion. Observation until regression is an option but it may take 6 to 8 months, and mandates diagnostic certainty. Unfortunately, there is also a concern for “malignant transformation” of these lesions. It is unclear if they degenerate into a malignancy or if they represented low-grade SCCA from the onset. There are reports of histologically confirmed KAs that have behaved as malignancies, including distant metastases.28 Watchful waiting while a possible SCCA is progressing is not clinically prudent. Therefore, surgical excision is probably the treatment of choice for KA, allowing complete pathologic analysis. Larger lesions of the face are best excised via Mohs’ techniques, although some are managed with intralesional injection of cytotoxic agents, with the goal of expediting involution.

Cysts

Cutaneous cysts of the face and neck are common yet frequently misunderstood in terms of etiology and classification. An epidermoid inclusion cyst is a true cyst in the sense that it is lined with stratified squamous epithelium and filled with keratin debris. Its etiology is unclear but it is postulated to arise from traumatic implantation of normal epithelial cells below the skin surface or de novo growth from deeper pilosebaceous units. When multiple cysts are found in a young child, one should consider Gardner’s syndrome in which multiple epidermoid cysts are found in this autosomal-dominant disorder associated with intestinal cancer. Treatment is usually direct excision and should include the entire specimen. Milia are similar inclusion cysts but are smaller, whitish lesions found in the superficial epidermal layer and often arise from suture or a skin resurfacing procedure, e.g., dermabrasion. The treatment for milia is either simple unroofing of the cyst, direct excision, or occasionally dermabrasion. Sebaceous cysts come from plugged sebaceous glands within the dermal layer. They can enlarge significantly and occasionally become infected or spontaneously rupture. Surgical excision is the optimal treatment. Dermoid cysts refer to an embryologic disorder, which occurs from an incomplete resorption of an embryologic tract, leading to entrapped ectodermal tissues and cyst formation. Normal embryologic fusion planes are areas of risk for dermoid cysts. Mucous cysts are small, almost translucent cysts found within mucous membranes and are not true cysts in that they are not epithelial lined. They are thought to arise from a disruption of a minor salivary gland duct.

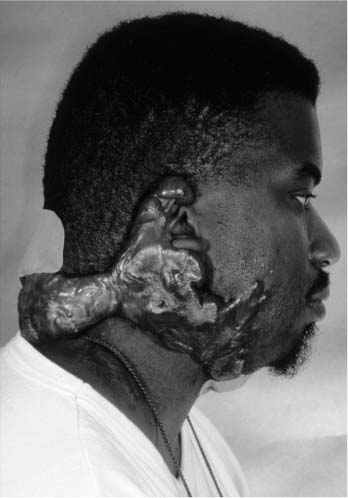

FIGURE 2-7 Keloid. Massive overgrowth of scar tissue.

Keloids are an extension of hypertrophic scars where the proliferation of fibroblasts and scar tissue extends beyond the boundaries of the original scar. They can lead to a massive overgrowth and present a tremendous therapeutic challenge (Fig. 2-7). Intralesional steroids, long-term pressure bandages or suits, and partial laser resection are treatment options with some success. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a locally aggressive tumor of fibroblasts that should be resected with wide surgical margins or via Mohs’techniques to minimize the risk of local recurrence. The infiltrative nature of this tumor often results in a larger cutaneous defect than first expected. Xanthelasma are large yellow plaques often found on the lower eyelids of adults and can be associated with elevated triglyceride levels. Treatment involves surgical resection or occasionally topical trichloroacetic acid or cautery. Syringomas are also yellow or flesh-colored lesions found on the eyelids of young adults. They tend to be smaller papules arising from eccrine sweat glands. Trichoepithelioma are flesh-colored nodules usually found on the eyelids, cheeks, and nose of young women. They may be multiple and can resemble a BCCA, even histologically.

Nonpigmented Malignancies

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCCA) is the most common malignancy found in humans, occurring most often on sun-exposed areas, the face and neck in particular, and are directly associated with chronic exposure to the sun’s ultraviolet rays (UVB). The nose is the most common subsite involved, followed by the cheeks and forehead. Cutaneous malignancies are more common in elderly men with fair complexion, those living at higher altitudes or closer to the equator, and in individuals with a history of significant exposure to the sun.

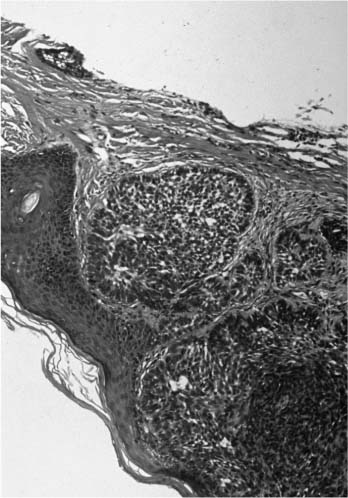

There are subtypes of BCCA (nodular, morpheaform, keratotic, and recurrent) that have distinct clinical and histologic features. Nodular BCCA is the most common type and classically presents as a well-circumscribed, nodular growth with a slightly translucent color, superficial telangiectasia, and little surrounding induration (Fig. 2-8). There may be a pearly border to the lesion that is characteristic of BCCAs, which becomes more evident when stretching the surrounding skin (Fig. 2-9). Less often, a BCCA contains areas of ulcerations or pigmentation. Patients often report a benign-appearing, small skin growth that may itch or occasionally bleed but does not resolve spontaneously. Histologically, the cell of origin for a BCCA is from the basal layer of the epidermis, which undergoes cytologic atypia and invades the basement membrane. With lower magnification, there is a collection of circumscribed, small, blue cells arranged in a nodular architecture. One of the pathognomonic signs is peripheral palisading, seen as a row of cells along the border of the lesion oriented in a distinct radial fashion (Fig. 2-10).

FIGURE 2-8 Nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCCA) of the nose. Note the circumscribed border, telangiectasia, and glossy appearance. (See Color Plate 2-8.)

FIGURE 2-9 Basal cell carcinoma with raised, pearly borders. (See Color Plate 2-9.)

FIGURE 2-10 Histology of a BCCA with nodules of small, dark blue cells and peripheral palisading. (See Color Plate 2-10.)

The other subtypes of BCCA tend to be more difficult to diagnosis clinically, behave more aggressively, and are more challenging to treat. The morpheaform BCCA, as its name implies, may be flatter, more yellow in color, and scar-like. The margins are indistinct with subclinical extension and dermal infiltration. There are often fibrotic and sclerosing features within the finger-like projections. Keratotic BCCA is also more elusive and is characterized by areas of keratin deposits with a field of typical BCCA. For this reason, the lesion is also referred to as a “basosquamous” carcinoma, although monoclonal antibody staining has demonstrated that it is a keratinizing BCCA rather than some intermediate neoplasm between a squamous and basal cell. Recurrent BCCA is considered a distinct subtype because of its varied clinical presentation, deviation from the traditional histologic forms, and unpredictable behavior. It readily infiltrates along previous scar planes and makes complete excision more challenging.

The treatment goal for all BCCAs is complete cure, and direct surgical excision remains one of the most common modalities used. Direct excision with a 2- to 3-mm margin and frozen-section control is generally adequate for classic nodular lesions where the borders are confidently seen. Other methods, such as cryotherapy or curettage and electrodesiccation, can be used for smaller and more superficial lesions and are probably the most widely used treatment. Ill-defined tumors, such as the morpheaform subtype, have finger-like projections that can be easily missed by simpler techniques and warrant Mohs’ surgical excision for acceptable cure rates and maximal tissue preservation. When Mohs’ surgery is not an option, the clinical margin should extend to at least 4 to 5 mm to capture the subclinical extensions. For smaller tumors in difficult locations, primary radiation therapy is a reasonable alternative and provides adequate cure rates when used selectively. It may also be indicated for those rare occasions when massive tumor growth has occurred and palliation is intended or as adjunctive therapy when there is extreme histologic aggression or evidence of perineural invasion.

There are several investigational and alternative treatments for BCCA. Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) blocks DNA synthesis in rapidly dividing cells and works well for premalignant lesions. Intralesional 5-FU has been effective for smaller BCCAs with cure rates between 80 and 90%.29 Photodynamic therapy with topical aminolevulinic acid as a sensitizer has shown some success as porphyrins and light-activated oxygen free radicals create tumor cell death.21 Finally, intralesional interferon-a may act as a cytokine and enhance the local T-cell cytotoxicity against tumor cells. Preliminary studies suggest cure rates of 80%.22,23

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA) is very similar to BCCA in terms of etiology and risk factors, occurring most often on sun-exposed areas of fair-complexioned adults with a history of actinic exposure. As a general rule, however, three important distinctions are made: (1) SCCAs tend to have more ill-defined borders, making simple excision less dependable; (2) they grow more rapidly; and (3) they are more likely to be associated with regional metastasis, especially lesions of the lower lip where cervical metastasis may occur in 10% of the cases. Depth of invasion has a greater prognostic impact in these lesions.

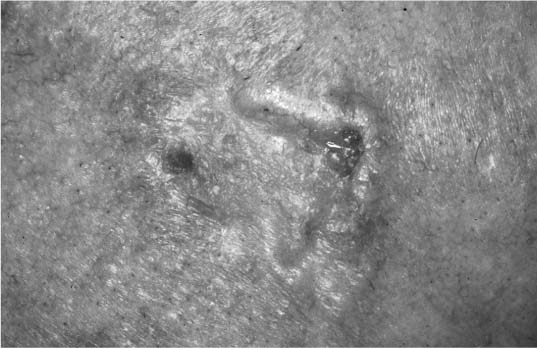

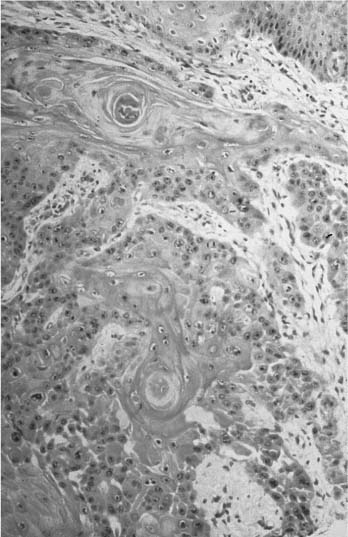

The typical clinical presentation of SCCA is similar to an aggressive actinic keratosis with scaling, an erythematous base, and a raised margin. It may also show ulceration, pigmentation, and a nodular form (Fig. 2-11). It has variable growth phases and occasionally takes on an extremely exophytic growth, resembling a keratoacanthoma. Histologically, the lesion is characterized by a deep infiltration of large keratinocytes, lightly staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and scattered, small, keratin pearls (Fig. 2-12). Different subtypes exist for SCCA: generic, adenoid, bowenoid, verrucous, and spindle. Bowenoid is the invasive counterpart to Bowen’s disease with infiltration below the basement membrane. Verrucous SCCA is more exophytic and verruciform, only invading deeper tissues with blunt, pushing borders. The spindle cell type is more aggressive and elusive to diagnose.

FIGURE 2-11 Squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA) that appears ulcerating, erythematous, has some pigmentation, and has less distinct borders. (See Color Plate 2-11.)

Treatment for some select superficial SCCAs and a majority of premalignant cutaneous lesions can be effectively managed nonsurgically with cryotherapy or with an aggressive resurfacing technique. Most confirmed SCCAs are managed with surgical excision utilizing slightly larger margins (at least 4-5 mm) due to the less discrete borders in contrast to those of BCCA. Furthermore, the threshold for Mohs’ surgery is lower with SCCAs of the face. Regional lymphatics are a greater consideration than with BCCAs due to the propensity for metastasis. Histologic evidence of perineural invasion portends a graver prognosis, and postoperative adjunctive radiation should be strongly considered. SCCAs arising on the ear and lips also behave in a more aggressive fashion and warrant a thorough investigation for metastatic disease as well as complete primary treatment.

FIGURE 2-12 Histology of a SCCA with nests of large, pink cells and occasional keratin pearls. (See Color Plate 2-12.)

Pigmented Lesions

Nevi

Skin pigmentation comes from the production of melanin by melanocytes in the basal epidermal layer. These cells are of neural crest origin and give rise to a variety of pigmented neoplasms of the skin. Melanocyte-associated tumors are found in the dermal layer rather than epidermis and are the cell of origin for both benign nevi and malignant melanomas. Nevi are classified into several subtypes.

Congenital Nevi

As the name implies, congenital nevi exist at birth and are found in a variety of sizes and locations. Most are relatively small, dark brown in color, and well circumscribed. Histologically, the pathognomonic feature of a congenital nevus is the presence of melanocytes adjacent to the pilosebaceous units. Melanocytes are otherwise present in all layers of the dermis. A subtype of the congenital nevus is the congenital giant (hairy) nevus where lesions are greater than 5 cm in diameter and often contain small amounts of hair. These larger lesions are significant for their malignant degenerative potential, especially into a malignant melanoma (10-20%). This risk increases with age, especially during puberty, and earlier definitive excision is recommended. Massive nevi (>20 cm) become high risk after the age of 1 and are ideally excised shortly after the first year of life. Many lesions require a staged, serial excision due to the elasticity of a child’s skin and limited recruitment potential with local flaps. Truncal nevi may not be practical to excise, and close serial observation with frequent biopsies may be the only option.

Junctional Nevi

Junctional nevi develop in young children and are a uniform brownish color, small, well circumscribed, and flat. As their name implies, the melanocytes are found at the dermoepidermal junction, and, because these cells are located more superficial than their adult counterparts, they tend to be darker in color. Although a great majority of all pigmented cutaneous lesions remain benign throughout life, this group has a risk of malignant degeneration, usually occurring after puberty. With time, the melanocytes appear to descend through the skin layers and “evolve” into the typical benign adult nevi. Treatment is dictated by concern for malignancy or cosmesis. When in doubt, a deep biopsy should be obtained. Aesthetic treatment includes direct excision, shave removal, or deep cryotherapy.

Halo Nevi

The halo nevus describes a stage of a clinical phenomenon where the host body rejects the involved melanocytes as well as the normal pigmented cells immediately surrounding the nevus. They usually occur on the back of children and may be associated with preexisting junctional nevi. The halo nevus presents as a central pigmented lesion that is well delineated and surrounded by a margin of depigmented, pale skin, resembling a “halo.” Left alone, these lesions often entirely resorb.

Compound Nevi

As melanocytes descend, they are found at both the dermoepidermal junction and within the dermis, thus a compound nevus. It often contains small amounts of hair and tends to be a lighter brown, circumscribed, slightly raised lesion characteristic of the typical adult “mole.” There does not appear to be a significantly increased risk for melanoma, and observation is the rule, unless cosmetic concerns exist. It “matures” into the classic intradermal nevus of adults.

Intradermal Nevi

With intradermal nevi, melanocytes are found exclusively in the deeper dermis and represent the common, non-pigmented nevus found in many older adults, especially on the face and scalp areas. The nevi can contain small tufts of hair, and they have the least malignant potential of the subtypes of nevi. The clinical presentation is varied and may be flat, raised, or even pedunculated, dark brown in color or entirely without pigment, smooth or rough in texture. Treatment is usually cosmetic and best managed with a superficial shave excision. When hair is present, it implies deeper involvement, and an elliptical or punch excision may be warranted.

Sebaceous Nevi

The sebaceous nevus of Jodassohn does not originate from neural crest melanocytes but is a congenital nevus frequently found on the scalp of young children. It appears as a yellow, fleshy, pebbly lesion that is well demarcated and without hair (Fig. 2-13). Size can vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. The nevus is usually circular in shape, although a linear form can be found on the face. Histologically, one finds a hypertrophy of sebaceous glands within the dermal layers and a hyperplasia of the epidermis. The nevus has three clinical phases: (1) at birth the sebaceous glands appear normal; (2) during childhood the glands reduce in number and size, making the lesion more inconspicuous clinically; (3) at puberty the glands undergo a rapid hypertrophy and the lesion appears to enlarge. It is during this third phase that cutaneous malignancies can arise, especially BCCAs, which have been reported in as many as 5 to 7% of patients with sebaceous nevi.11 For this reason, the treatment of choice for sebaceous nevi is complete excision before puberty. Appendical tumors such as syringocystadenoma also occur within these nevi.

Blue Nevi

Blue nevi are less common and appear as smaller, hairless lesions on the face and neck of older individuals. The melanocytes are often found in deeper layers, including into the subcutaneous fat, thus giving rise to the deep blue color and requiring deeper excision for treatment.

FIGURE 2-13 Nevus sebaceous of scalp in a child. (See Color Plate 2-13.)

Spitz Nevi

The Spitz nevus is an uncommon lesion more often found in children, also known as a “juvenile melanoma.”It tends to be rapid growing, found on all parts of the body, and has a pink or even red tint to it. Most lesions are raised or dome shaped and firm to palpation. They are difficult to distinguish from a malignant melanoma, although true malignant degeneration is not seen. Treatment is dictated by clinical suspicion, and once the diagnosis is confirmed, it can be managed with aesthetic priorities.

Lentigo Senilis

This is also known as “solar lentigos,” “actinic lentigos,” or “liver spots.” It is a very common lesion appearing as a light brown, macular spot with an irregular border found on sun-exposed areas, particularly the hands and face of older individuals. On rare occasion, several lesions may coalesce to create a single larger lesion. It has no malignant potential and is often confused with seborrheic keratosis. Treatment is best with chemical agents such as deeper peels or bleaching agents. Cryotherapy is an alternative option.

Lentigo Maligna

Lentigo maligna is a precursor to the malignant melanoma and can be considered an intraepithelial in situ melanoma with the potential for progression into an invasive lentigo maligna melanoma. These lesions also occur on the sun-exposed surfaces of elderly individuals and are thought to carry about a 5% risk of becoming a frank melanoma. This progression of disease is thought to be heralded by a change in contour with a nodular area developing within a previously flap lesion. Treatment is surgical excision with a 5-mm margin peripherally and down to the subcutaneous fat. It must be recognized that the final pathologic review may uncover a malignant melanoma within the specimen, in which case the margin would have been inadequate and reexcision is warranted.

Malignant Melanoma

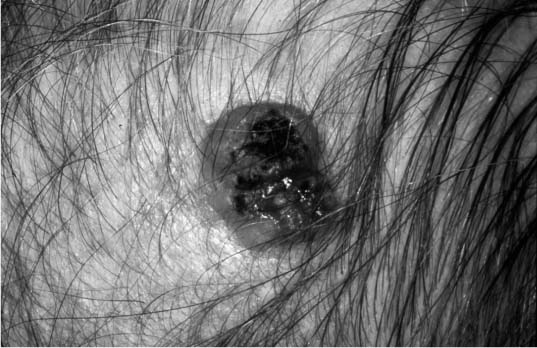

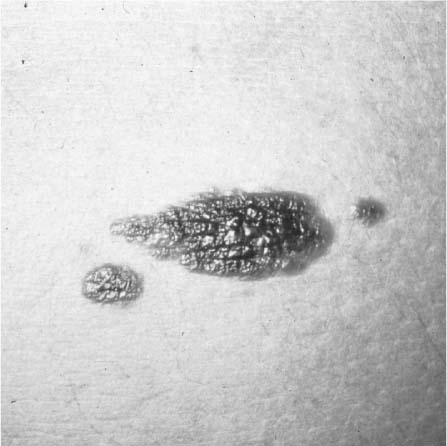

Malignant melanoma is the third most common skin cancer but an entirely different entity in many ways, the most significant being the prognosis and its potentially lethal outcome; it is responsible for over three quarters of all deaths from cutaneous malignancies and has the No. 1 fastest growing incidence in the United States. Like the other cutaneous neoplasms, it tends to occur on sun-exposed areas; however, malignant melanomas do not adhere to this rule as consistently. Because most adults have scattered benign pigmented lesions, early and accurate diagnosis is often delayed. There are four distinct clinical characteristics for melanoma (A to D), and a change in them over several months is a particularly ominous sign: A stands for asymmetry in topography or shape; B stands for the border of the lesion, which may be irregular; C stands for color variability within the lesion; and D stands for diameter, as in larger lesions (>6 mm) or a change in size. Finally, satellite lesions around the primary tumor raise the suspicion for a malignant melanoma (Fig. 2-14).

FIGURE 2-14 Malignant melanoma. Note the asymmetric topography, irregular borders, color variegation, and satellite lesions. (See Color Plate 2-14.)

Definitive diagnosis is made histologically with special immunohistochemical stains for cells of neural crest origin, i.e., S-100 or HMB-45.

Different subtypes of malignant melanoma exist and reflect different growth patterns. Superficial spreading is the most common and usually has the characteristic signs of color variability, irregular borders, and nodularity. The radial growth phase usually precedes the vertical phase for a variable period of time. Nodular melanoma is the most aggressive subtype, having an early vertical growth phase. Fortunately, it is not common, occurring in less than 10% of melanoma cases. Lentigo maligna melanoma has the best prognosis and is most often found on sun-exposed areas of elderly patients. It evolves from the benign precursor, lentigo maligna, also known as the “Hutchinson’s freckle,” and may grow in a radial fashion up to several centimeters. Acral lentiginous is the most common melanoma subtype in African Americans, usually occurring on the acral surfaces such as the hands, feet, and anogenital mucosa. Although its prognosis is quite poor, it only makes up 5 to 7% of melanomas.

Prognosis is most determined by tumor depth, and the staging classification has recently been revised to incorporate better tumor ulceration, regional metastasis, and tumor depth. The Clark level, describing tumor thickness based on histologic layer, e.g., papillary dermis versus reticular dermis, has been limited to only the smallest lesions. The Breslow thickness (measured in millimeters from the basal layer of the epidermis) has greater prognostic significance, and because the depth is so critical in staging, an accurate biopsy must include the deep margin. Tumor ulceration can influence this vertical measurement but it is now accounted for and its mere presence will advance the tumor stage. The current staging system also uses whole numbers for depth of invasion: stage I, <1 mm; stage II, 1 to 2 mm; stage III, 2 to 4 mm; and stage IV, >4 mm (Table 2-3).

The primary treatment for malignant melanoma is wide local excision, but there is a trend toward decreasing the margin.30 For melanoma in situ, a 5-mm margin is adequate. Tumors less than 1 mm in depth are excised with a 1-cm margin, whereas those greater than 1 mm in vertical depth should have a 2-cm margin, even on the face. Regardless of depth, a margin in excess of 2 cm has not lowered recurrence rates or improved survival.30,31 Melanomas in excess of 4 mm in depth have a 5-year survival rate of less than 50%, and this statistic does not change with wider excisional margins.32,33 The best management for potential lymphatic spread is unclear, but it is generally accepted that for lesions greater than 4.0 mm in vertical depth, a staging/prophylactic neck dissection should be performed. For lesions between 0.75 and 4.0 mm in depth, intralesional lymphoscintigraphy with sentinel node biopsy may prove to be effective.34–36 Lesions less than 0.75 mm are usually managed locally only.

LOCAL AND REGIONAL CUTANEOUS FLAPS

FLAP PHYSIOLOGY

The creation of cutaneous flaps disrupts the normal vascular network and an alternate flow is immediately established. In the face and neck, the subdermal arcade is typically robust enough to allow one to place significant tension and stress on the pedicle without jeopardizing the skin paddle. It has been long believed that a wider pedicle base allows for greater vascular inflow and that the length of the flap is dictated by its width, thus giving rise to the dictum of a minimum length/width ratio of 3:1. The fallacy of the length/width ratio has been demonstrated, and it is currently accepted that the perfusion pressure at the flap base is the most significant variable in terms of ensuring flap viability.37,38 This understanding has directed the development of ways to enhance flap perfusion and viability. The forehead flap is an example of how a long, narrow pedicle can support a flap through its rich perfusion pressure at the pedicle base.

A second important understanding in flap physiology is the recognition of venous congestion and the impact it has on flap toxicity. Cutaneous flaps of the face are more likely to suffer from venous congestion than arterial ischemia, and its distinction and prompt intervention is imperative. There are several ways to address acute venous congestion of a flap, e.g., medicinal leeches, hyperbaric oxygen, release of skin sutures, or returning the flap to its site of origin. (Flap salvage is further discussed later in this chapter.)

| Stage | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| IA | Tumor ≤ 1.0 mm without ulceration; no lymph node involvement; no distant metastases |

| IB | Tumor ≤ 1.0 mm with ulceration or Clark level IV or V |

| Tumor 1.01- 2.0 mm without ulceration; no lymph node involvement; no distant metastases | |

| IIA | Tumor 1.01- 2.0 mm with ulceration |

| Tumor 2.01- 4.0 mm without ulceration; no lymph node involvement; no distant metastases | |

| IIB | Tumor 2.01- 4.0 mm with ulceration |

| IIIA | Tumor >4.0 mm without ulceration; no lymph node involvement; no distant metastases |

| IIIB | Tumor >4.0 mm with ulceration; no nodal involvement; no distant metastases |

| IVA | Tumor of any thickness without ulceration with one positive lymph node and micrometastasisa or macrometastasisb |

| IVB | Tumor of any thickness without ulceration with two to three positive lymph nodes and micrometastasisa or macrometastasisb |

| IVC | Tumor of any thickness and macrometastasisb OR in-transit metastases/satellites without metastatic lymph nodes, OR four or more metastatic lymph nodes, matted nodes, or combinations of in-transit metastases/satellite(s), OR ulcerated melanoma and metastatic lymph node(s) |

| IV | Tumor of any thickness with any nodes and metastases |

Note: Ulceration is the absences of an intact epidermis overlying a portion of the primary melanoma based on pathologic microscopic observation of the histologic sections.

aMicrometastases are diagnosed after elective or sentinel lymphadenectomy

Methods of enhancing flap viability are of great clinical interest and have been widely studied. Flap delay is a time-tested way of improving viability, and its efficacy is reproducible.”Delay”is accomplished by incising around the border of the intended flap as a preliminary stage, or alternatively elevating a portion of the flap but immediately replacing it back to the donor site. The definitive stage is performed 7 to 14 days later. Although the impact of improving flap perfusion can be dramatic, its mechanism of action remains poorly understood with conflicting hypotheses.39–46

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree