Other T/NK-cell lymphomas that may involve the skin994

Other B-cell lymphomas that may involve the skin996

Precursor B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma996

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (B-CLL)996

Mantle cell lymphoma997

Primary effusion lymphoma997

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (LL/M)997

Burkitt and Burkitt-like lymphoma998

Plasmacytoma and secondary myeloma998

Lymphoid hyperplasias mimicking primary lymphoma1000

Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia simulating B-cell lymphoma1000

Lymphomatoid drug reactions1001

Reactions resembling CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders1002

Pseudolymphomatous folliculitis1002

Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate1002

Acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma1003

Cutaneous CD8+ T-cell infiltrates in HIV/AIDS1003

Miscellaneous1003

INTRODUCTION

The diagnosis and classification of cutaneous lymphomas remain one of the most challenging areas of dermatopathology. At the time the last edition of this book was published, the WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues based on the REAL classification of lymphomas was being published.1. and 2. This classification included some cutaneous lymphomas as subgroups within the main classification framework. At the same time, the Project Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer published a classification of cutaneous lymphomas which came to be known as the EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas. 3 Those two classifications were based on a combination of histological, clinical, immunohistological, and cytogenetic features. There were certain differences in terminology and emphasis between these two classifications and the appropriateness of one or other of the classifications was debated in the literature.4.5.6.7.8.9.10.11. and 12. The EORTC classification included only those lymphomas which appeared to be unique to the skin. The REAL/WHO classification had the advantage of including other lymphomas which involved the skin secondarily or rarely as ‘primary’ cutaneous lymphomas. 13 Other proposals were made for a stand-alone classification of cutaneous lymphomas based on the REAL/WHO classification.13. and 14.

Recently, a consensus classification of cutaneous lymphomas, the WHO/EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas, has been published15. and 16. and critiqued in the literature.16.17. and 18. This compromise classification defines ‘primary cutaneous lymphomas’ as lymphomas that present in skin with no evidence of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis. There are some inherent problems with this strict definition of primary cutaneous lymphoma as some putative primary cutaneous lymphomas are associated with systemic spread to other systems at the time of presentation, e.g. Sézary syndrome and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. The definition does not encompass secondary cutaneous lymphomas. Nevertheless this classification is widely used and will be used as the framework for the discussion in this chapter (see Table 41.1). Other lymphoma entities which only rarely present in the skin or do so as part of systemic spread of lymphoma from another site are classified according to the general WHO classification of lymphomas.

| Cutaneous T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas |

Mycosis fungoides and subtypes Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides Pagetoid reticulosis Granulomatous slack skin Hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoma Sézary syndrome Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma Primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma Lymphomatoid papulosis Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type Primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma (provisional) Cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma (provisional) Primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma (provisional) |

| Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas |

Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma Primary cutaneous follicle center cell lymphoma Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, other Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma Plasmablastic lymphoma T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma Lymphomatoid granulomatosis |

| Precursor hematologic neoplasm |

| Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm |

| Other T/NK-cell lymphomas that may involve the skin |

Precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma Primary systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma Intravascular T- and NK-cell lymphoma Aggressive NK-cell leukemia Other T/NK-cell lymphomas and leukemias |

| Other B-cell lymphomas that may involve the skin |

Precursor B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma Mantle cell lymphoma Primary effusion lymphoma Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia Burkitt and Burkitt-like lymphoma Plasmacytoma and secondary myeloma |

| Other lymphomas |

| Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Cutaneous infiltrates of leukemias |

| Myeloid leukemias, myeloproliferative diseases and myelodysplastic syndromes |

| Lymphoid hyperplasia mimicking primary lymphoma |

Lymphoid hyperplasia simulating B-cell lymphoma Lymphomatoid drug reactions Reactions resembling CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders Pseudolymphomatous folliculitis Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate Acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma Cutaneous CD8+ T-cell infiltrates in HIV/AIDS |

| Cutaneous infiltrates in post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders |

| Other lymphoproliferative disorders associated with immunosuppression |

Methotrexate-associated lymphoproliferative disorders Cutaneous infiltrates in HIV/AIDS |

| Miscellaneous |

| Extramedullary hematopoiesis |

The current diagnosis of lymphomas requires some knowledge of lymphocyte ontogeny and techniques which are used to demonstrate such aspects as cell phenotype, clonality of a proliferation, and cytogenetic features including the presence of viral genetic material. Most laboratories are now able to perform these techniques, including immunohistochemistry, in-situ hybridization, polymerase chain reaction technology (PCR), and fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH).19.20.21. and 22. Flow cytometry is also used for immunophenotyping23 but unlike other organs, the number of neoplastic cells present in skin is sometimes small and cells are difficult to extract, particularly those in the epidermis. Enzymatic and mechanical disintegration methods have been used to extract cells. 24

Other techniques, such as gene expression profiling using cDNA microarray technology and serum proteomics, are being used to more clearly define subgroups of cutaneous lymphoma, distinguish between cutaneous lymphoma and inflammatory dermatoses, and identify prognostic groups.25.26.27.28.29. and 30.

The significance of established clonality of either B or T cells in cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates remains a problem of interpretation.31. and 32. Although it has often been stated that lymphocyte clonality is not equivalent to malignancy33 demonstration of clonality in the appropriate cellular infiltrate and clinical scenario should be regarded as lymphoma.3. and 34. Follow-up studies on atypical lymphoid infiltrates with demonstrated monoclonal populations of T or B lymphocytes have shown progression to clear-cut lymphoma in some cases.34. and 35. Follow-up may be needed over a long period because of the slow evolution and indolent behavior of many cutaneous lymphomas. Patients with a primary cutaneous lymphoma have an increased risk of developing another lymphoproliferative disorder. 36

Most antibodies used for phenotyping and assessment of proliferation are available for use on paraffin-embedded tissue. Currently used antibodies and their various specificities are listed in Table 41.2. 37

| Antibody | Predominant cells |

|---|---|

| CD1a | Langerhans cells, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, some T-lymphoblastic lymphomas |

| CD2 | T cells and T-cell lymphomas |

| CD3 | T cells and T-cell lymphomas |

| CD3ε (cytoplasmic CD3) | T cells, NK cells, T-cell neoplasms, NK-cell neoplasms |

| CD4 | T-helper cells, monocytes, macrophages, Langerhans cells, peripheral T-cell lymphomas, MF, HTLV-1 associated adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma |

| CD5 | T cells, T-cell lymphoma, B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma |

| CD7 | T cells, T-cell lymphomas, myeloid leukemia, NK-cell neoplasms, T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia |

| CD8 | T-cytotoxic/suppressor cells, NK cells, T-cell lymphomas, e.g. subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma |

| CD10/(CALLA) | Precursor B cells, B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, follicle center cell/follicular lymphoma |

| CD15 | Neutrophils, monocytes, Reed–Sternberg cells (classical Hodgkin lymphoma), acute myeloid leukemia |

| CD20 | B cells, B-cell lymphomas |

| CD21 | Follicular dendritic cells, follicular dendritic cell neoplasms, mantle and marginal zone B cells |

| CD23 | Follicular dendritic cells, mantle zone B cells, B-small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| CD30 | Activated lymphoid cells, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis, Reed–Sternberg cells (classical Hodgkin lymphoma), embryonal carcinoma |

| CD43 | T cells, myeloid cells, mast cells, T-cell lymphomas, some B-cell lymphomas, myeloid leukemia, mast cell neoplasms |

| CD45 (leukocyte common antigen, LCA) | Hematolymphoid cells, most B- and T-cell lymphomas |

| CD45RO | T cells, histiocytes, myeloid cells, T-cell lymphomas, histiocytic neoplasms, myeloid leukemias |

| CD56 | NK cells, subset of activated T cells, T/NK-cell neoplasms, subset of T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma |

| CD57 | NK cells, T-cell subset, subset of T-cell neoplasms, NK-cell neoplasms |

| CD68 | Histiocytes, myeloid cells, mast cells and their neoplasms |

| CD79a | Immature and mature B cells, B-cell lymphomas, plasma cells, plasma cell neoplasms |

| CD99 | T- and B-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia, small round cell tumors (Ewing’s sarcoma/PNET, synovial sarcoma, and others) |

| CD117 (KIT gene product) | Mast cells and mast cell disorders, some myeloid leukemias, Merkel cell carcinoma |

| CD123 | Plasmacytoid dendritic cells, blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm |

| CD138 | Plasma cells, some B immunoblasts, plasma cell neoplasms, some carcinomas |

| ALK-1 | Some types of anaplastic large cell lymphoma |

| βF1 | Major population of T cells (αβ T cells) not NK cells, most T-cell neoplasms |

| Bcl-2 | Non-germinal center B cells, most T cells, most follicular lymphomas but only some cutaneous follicle center cell lymphomas, many other B-cell neoplasms |

| Bcl-6 | Germinal center B cells, follicular lymphoma including cutaneous follicle center cell lymphoma |

| Bob.1 | B cells including plasma cells, B-cell neoplasms, plasma cell neoplasms |

| Cyclin D1 | Some histiocytes, mantle cell lymphoma |

| Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) | Plasma cells, plasma cell neoplasms, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis, nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, many epithelial neoplasms, epithelioid sarcoma |

| EBV-latent membrane protein-1 (LMP-1) | Hodgkin lymphoma, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, some NK/T-cell neoplasms |

| Granzyme B, perforin, TIA-1 | NK cells, cytotoxic T cells, several T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms |

| Immunoglobulin light chains (kappa and lambda) | Plasma cells, plasma cell neoplasms, plasmacytoid neoplasms |

| Ki-67 | Proliferating cells |

| MUM1 | Plasma cells, small percentage of B and T cells, plasma cell neoplasms, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, some large B-cell lymphomas, other B-cell lymphomas, Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Myeloperoxidase | Myeloid cells, myeloid leukemias |

| Oct-2 | B cells including plasma cells, B-cell neoplasms including plasma cell neoplasms |

| Pax5 | B cells except plasma cells, B-cell lymphomas including B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, small cell carcinomas and Merkel cell carcinoma |

| TDT (terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase) | Precursor B, T, or NK cells, B- and T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm |

CUTANEOUS T-CELL AND NK-CELL LYMPHOMAS

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of neoplasms which show considerable variation in clinical presentation, histopathology, and prognosis.41. and 42.

The development of techniques to establish T-cell clonality in infiltrates in the skin has greatly contributed to the diagnosis of these disorders; they must still be interpreted in conjunction with conventional histology and immunohistochemistry.43. and 44. Rearrangement of T-cell receptor genes (TCR) α,β,γ,δ results in diversity which can be exploited by PCR and Southern blot technology to establish clonality.21.45. and 46. The majority of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas express the αβ TCR but all αβ TCR-positive cells express at least one rearrangement of the γ-chain allele and the TCR-γ gene is frequently assayed to establish clonality using a limited number of primers.43. and 44. However, it has been demonstrated that the use of a comprehensive set of primers is required to give an optimal detection rate of TCR-γ gene rearrangements. 45

It has been suggested that the detection of a clonal process in a polyclonal background is more readily detected with assays directed at the TCR-β locus. 47 Multiplex PCR assays detect virtually all clonal T-cell populations and have the added advantage of detecting γδ proliferations. 48

There are reports of complete regression of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas after biopsy. 49

KIT (CD117) expression is very rare in all types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. 50

Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas occurring after organ transplantation are rare and do not have the usual prognosis associated with particular subsets. 51

There are reports of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma evolving from Ofuji papuloerythroderma. 52 This entity is further discussed on page 508.

MYCOSIS FUNGOIDES AND SUBTYPES

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a clinically and pathologically distinct form of cutaneous lymphoma characterized by an epidermotropic infiltrate of small to medium-sized T lymphocytes. In the WHO/EORTC classification, the term is reserved for those cases having classical features in which there is progression from patches to plaques to tumors (the Alibert–Bazin type) or variants which have a similar course.15. and 53.

Although it represents almost 50% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas,15. and 54. it is still uncommon. True incidence figures of MF are difficult to collate as clinical subtypes of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) are not clearly distinguished in many registries.54.55. and 56. There appears to be a rising incidence of CTCL in the United States. 57 There are differences in incidence among various racial groups.57.58. and 59. It usually arises in late adulthood.60.61.62.63. and 64. There is a definite male predominance. 64 It has been reported in identical twins, 65 and very rarely in families66. and 67. or spouses. 68

Lesions tend to develop on the lower part of the trunk and thighs, and on the breasts in females. 69 In advanced stages the entire body may be affected including the face and scalp. The palms and soles have been involved in some cases. MF typically has an indolent course with slow progression over years or decades. 3 In one study of progression of MF from patch stage to death from systemic spread, the overall average disease duration was 12.4 years. 70

MF is rare in children and young adults.64.71.72. and 73. Lesions in children are frequently hypopigmented, particularly in dark-skinned individuals.74. and 75. MF arising in children or young adults is not more aggressive than that appearing in adult life.72. and 74. Young patients with limited skin disease may have a slightly better disease-specific survival than older patients. 71

The etiopathogenesis of MF is unknown. There appears to be an association with particular HLA class II subtypes but not HLA class I subtypes. 76 There is no good evidence that it is linked to viruses such as HTLV-1, HHV-8, or HTLV-5.77.78.79.80.81.82.83.84.85.86.87.88. and 89. Most cases of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in HIV/AIDS patients are erythrodermic, have a CD8+ phenotype, and are rapidly progressive. It has been suggested that MF arises in a background of chronic inflammation as a response to chronic antigen stimulation. 90 There is controversy as to the existence of a preceding stage (premycotic eruption), and its nature.91. and 92. Rare cases have been reported after solid organ transplantation. 93

Although the characteristic evolution of MF is from patch through plaque to tumor, 94 this is not invariably the case.71. and 95.

Intractable pruritus is sometimes present, occasionally preceding the appearance of skin lesions by years. 96 Histological evidence of MF has been identified in the skin of some of these cases despite the apparent absence of lesions.97. and 98.

Almost all cases of MF are a monoclonal proliferation of CD4+ cells. This has been established by PCR for TCR gene rearrangement in from 52% to 90% of cases. 34 Not all the cells in lesions are neoplastic: many are reactive. 99 Micromanipulation and laser-beam microdissection have demonstrated a monoclonal population of T cells in the epidermis in early (patch stage) lesions of MF.39. and 99. Polyclonal (reactive) T lymphocytes are more common in the dermis than are clonal T lymphocytes in these lesions. 99

Although it is classified as a primary cutaneous lymphoma, 15 circulating clonal T cells can be demonstrated in the peripheral blood even in early stages of MF by sensitive PCR techniques. 100 Clones are identical to those in the skin. 101

An MF-like picture has been associated with therapeutic ingestion of carbamazepine, 102 captopril, 103 quinine, 104 fluoxetine, 105 and phenytoin;106. and 107. the eruption cleared in each instance following cessation of the drug. 107

The patch stage consists of ill-defined patches of varying hue, often with a fine scale. They are irregular in size and shape and have a random distribution, usually on the trunk. This stage may persist for many years before progression occurs.70. and 108.

It seems appropriate to regard large plaque parapsoriasis (LPP) as early MF as 10–30% of cases progress to overt MF.91.109.110. and 111. Clonal TCR gene rearrangements have also been identified in a proportion of cases. 112 Poikiloderma atrophicans vasculare is the atrophic form of the patch stage of MF. 113 On the other hand there is less acceptance that small plaque parapsoriasis (digitate dermatosis, chronic superficial scaly dermatitis) is early MF despite views to the contrary (see p. 119).96.111.114.115. and 116. If progression does occur it is a rare event. In a recent study of 27 cases of small plaque parapsoriasis, followed for a mean of 10 years, there was apparent progression to plaque stage MF in only one case. 117

The plaque stage is characterized by well-demarcated lesions which are often annular or arciform in arrangement. They are red to violaceous in appearance and occasionally scaly. 113 The plaques may develop de novo or from patches. In the early stages, lesions are often limited to less than 10% of the skin surface, but they may be more widespread, particularly in the late plaque stage. 113

Large plaque parapsoriasis is characterized by irregular erythematous patches with minimal scale rather than plaques as the name implies. 111 Lesions occur on the trunk and major flexures and are usually larger than 6 cm in diameter.109. and 111. With time, atrophic (poikilodermatous) change may supervene in a proportion of cases. 111

Tumors usually develop in pre-existing lesions. 94 The tumors are violaceous to deep red in color, with a tense shiny surface. Ulceration may occur. The lesions usually measure 1 cm in diameter or more.

In one series which examined the progression of the disease through various stages, the average duration of the patch stage was 7.2 years, the plaque stage 2.3 years, and the tumor stage 1.8 years. 70

The term ‘d’emblee form’, used in the past to refer to cases presenting with tumors that were not preceded by patches or plaques, should no longer be used as most represent other T- and B-cell lymphomas which present with tumors.42. and 118.

There is a long list of non-classic presentations of MF64.119. and 120. which although not the typical Alibert–Bazin type have a behavior similar to classic MF. These include hypopigmented lesions,121.122.123.124.125.126.127.128. and 129. hyperpigmented lesions,87. and 130. leukoderma, 131 bullae,132.133.134.135.136.137. and 138. dyshidrotic lesions, 139 perioral dermatitis-like lesions, 140 palmar-plantar lesions,141.142. and 143. papules,144.145. and 146. pustules, acneiform, hyperkeratotic, verrucous,147.148. and 149. poikilodermatous, 150 anetodermic, 151 annular erythema, 152 granuloma annulare-like, 153 pyoderma gangrenosum-like, 154 and plaques resembling acanthosis nigricans,155. and 156. or keratosis lichenoides chronica. 157

At present, so-called ‘syringotropic MF’ is not regarded as a separate entity, unlike folliculotropic MF.64.158. and 159. By itself, it may present with punctate erythema. 160 Syringotropism can be seen in otherwise classic MF and in folliculotropic MF.160.161.162. and 163. In many cases syringolymphoid hyperplasia, characterized clinically by scaly plaques associated with hair loss and anhidrosis, represents a T-cell lymphoma.164. and 165. Rarely there may be erythroderma. 166

Acquired epidermal cysts, 167 nail dystrophy,167. and 168. neutrophilic dermatoses, 169 and acquired ichthyosis170.171. and 172. have been reported in association with MF. Second neoplasms including skin cancers, other lymphomas, and internal malignancies have also been reported, some apparently related to therapy.173.174.175. and 176. Oral lesions occur rarely.177. and 178.

MF-associated mucinosis is now classified separately as a variant of MF with folliculotropic MF and is discussed separately.

MF may also present as purpuric lesions (see p. 232) which resemble or are indistinguishable from the pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPD).179.180.181. and 182. Clinical suspicion should be aroused when the distribution of purpuric lesions is unusual for one of the forms of PPD, or lesions are extensive, long-standing and have a reticular pattern. 179 The separation of the two conditions is not always possible by routine histology or even with TCR gene rearrangement studies. 180

Solitary lesions with the histopathology of early MF, and distinct from pagetoid reticulosis, have been reported,183.184.185.186. and 187. sometimes in unusual sites (penis). 188 In one small series of such cases, clonal TCR gene rearrangement was found in 50% of cases. No evidence of progression to classic MF was observed in any of the cases. 184 It is not clear if these lesions represent true lesions of MF or are simulants. 189

Erythroderma can develop at any stage in the evolution of MF. 94 The distinction between Sézary syndrome (SS) and erythrodermic MF is based on the absence of significant numbers of circulating ‘Sézary cells’ in the peripheral blood as defined below. When hematologic findings fulfill the criteria for Sézary syndrome the condition is classified as ‘secondary SS’ or ‘SS preceded by MF’. 190

Circulating T lymphocytes exhibiting the same clonal TCR gene rearrangements as those in skin lesions can be found even in early stages of MF. 101

Involvement of lymph nodes and other organs may occur in late stages of the disease. 191 Lymphadenopathy in the early stages is due in most cases to dermatopathic lymphadenopathy, a reactive condition that may be seen in lymph nodes draining skin affected by a variety of inflammatory dermatoses as well as MF. 192 However, sensitive PCR techniques have shown involvement of lymph nodes by clonal T lymphocytes even at early stages of MF.193.194. and 195. Molecular evaluation of lymph nodes for staging purposes has been investigated,196. and 197. but detection of a monoclonal population of T cells by PCR of lymph nodes does not appear to be superior to clinical and histological examination of lymph nodes in predicting clinical outcomes. 198 Grading of more than one lymph node for staging purposes is reported to be more accurate than for a single node. 199 The detection of clonality by Southern blot techniques may be more useful in predicting outcome than using more sensitive PCR techniques. 200 One study concluded that detection of a monoclonal population of T cells in lymph nodes by Southern blot analysis194 or by more sensitive PCR techniques201 was predictive of a poor clinical outcome and reduced probability of survival. Detection of a monoclonal population in peripheral blood is also an adverse feature. 202 Visceral involvement is frequently found at autopsy. The lung, spleen, liver, and kidney are most frequently involved but every organ can be infiltrated by tumor cells.203.204.205.206. and 207.

There have been numerous studies on the prognosis and survival in patients with MF.208.209.210.211.212.213.214. and 215. Different and developing treatment modalities would be expected to alter the prognosis of MF in the future.

The clinical course of MF is quite variable; in the majority of cases it is indolent. Spontaneous resolution of individual lesions may occur at any time during the disease. The estimated 5-year survival of patients in the EORTC series was 87%. 3 Patients are staged T1 to T4 (T1 = limited patch/plaque, T2 = generalized patch/plaques, T3 = tumor, T4 = erythroderma). Patients with stage T1 disease have a very favorable outcome; their life expectancy is not altered by the disease. 216 In a recent study of long-term outcome for patients with MF and Sézary syndrome, age, stage (T classification), and the presence of extracutaneous disease were important predictors of survival. 214 Development of extracutaneous lymphoma has been reported in cases of late-stage MF treated with bexarotene. 217 Transformation to a large cell lymphoma218 is a bad prognostic feature.219.220.221. and 222. In one series, those cases with a CD30+ large cell transformation had a better prognosis that those with a CD30− phenotype. 221 CD30+ large cell transformation has been reported after PUVA, and alefacept therapy for MF. 223 Second B-cell lymphomas have been reported in patients with pre-existing MF. 224

Serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC/CCL17) levels are useful for assessing the disease activity in patients with MF. 225

The outcome of patients with juvenile-onset MF is similar to that of adult-onset disease. 73 Pregnancy appears to have no impact on the course of early stage MF. 226 PCR for clonal T-cell rearrangements has identified residual disease in a third of patients with complete clinical remission. 227

Histopathology

There is considerable literature on the histological diagnosis of mycosis fungoides, particularly in the early stages.228. and 229. A combination of routine histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and gene rearrangement studies is now possible. All have their limits. Attempts have been made to ‘weigh’ the importance of various histological parameters in arriving at a diagnosis.230. and 231. Multiple biopsies over a period of time are often needed for a diagnosis. Biopsy appearances can be altered by therapies such as corticosteroids and UVA therapy. Many studies have shown that interobserver agreement on the histological diagnosis of MF is not high. 232 Despite the use of other techniques, some authors maintain that the diagnosis of early MF still depends on clinical features and conventional histology and recommend further biopsies where there are no clear-cut diagnostic features in a biopsy. 233

Patch stage

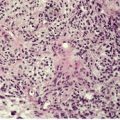

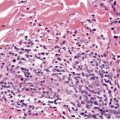

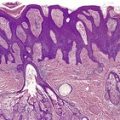

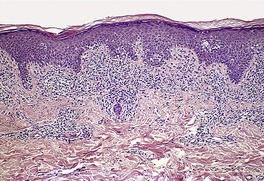

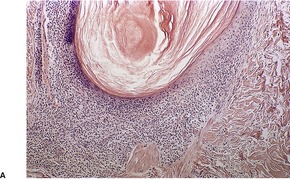

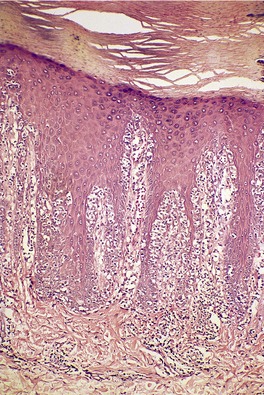

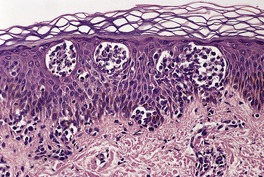

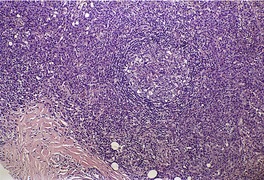

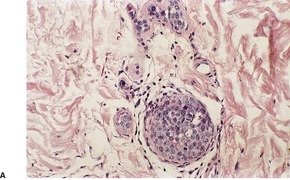

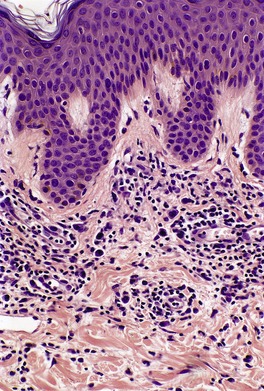

In the patch stage of MF a combination of architectural and cytological features is used to make the diagnosis. This includes changes in the epidermis and dermis. In the earliest stage there is a relatively sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes spread along the slightly expanded papillary dermis with little tendency to aggregate around vessels of the superficial plexus. Within the epidermis, lymphocytes are typically confined to the basal layers of the epidermis, either as single cells in a ‘string of beads’ arrangement or as small groups of cells (Fig. 41.1). These cells are often surrounded by a clear ‘halo’, a ‘meaningful artifact’ not caused by mucin accumulation. 234 There is usually little or no spongiosis.235. and 236. The Pautrier microabscess (sharply marginated discrete clusters of lymphocytes in close apposition with one another, within the epidermis) is, when strictly defined, highly characteristic of MF (Fig. 41.2). They are uncommon in the patch stage, however, and if this feature is given undue importance many cases of MF will be missed.237. and 238. Occasionally the histological appearance mimics a melanocytic lesion. Atypia of cells may be minimal in earlier stages of MF but in some cases, the epidermal lymphocytes are larger that those in the dermis. 92 Cytological abnormalities may be seen in thin plastic sections that are not apparent in conventional sections. 103 There is frequently, but not invariably fibrosis in the papillary dermis in the form of haphazardly arranged wiry collagen bundles.92. and 103. The epidermis may show mild acanthosis; in poikilodermatous and atrophic lesions the epidermis is thin. 235 Necrosis of the epidermis is occasionally present. 228 Basal vacuolar change and pigment incontinence are present in these lesions. 239 In some cases there is a marked lichenoid reaction with histology resembling lichen planus. Unlike lichen planus there may be plasma cells and eosinophils in the dermal infiltrate as well as atypical lymphocytes. Infiltration of eccrine sweat duct structures may be seen in patch and other stages of MF and may remain after therapy.240. and 241.

|

| Fig. 41.1 Mycosis fungoides. There is a band-like dermal infiltrate with atypical lymphocytes in the basal epidermis. (H & E) |

|

| Fig. 41.2 Mycosis fungoides. A collection of epidermal atypical lymphocytes forming a Pautrier microabscess. (H & E) |

The diagnostic changes in large plaque parapsoriasis may be subtle with epidermal changes of mild psoriasiform hyperplasia, overlying mild orthokeratosis and spotty parakeratosis, and a sparse dermal cellular infiltrate. The dermal infiltrate may extend upward into and fill the dermal papillae. Pautrier microabscesses are not seen and cellular atypia is often minimal. 242 The atrophic lesions have identical changes to other atrophic lesions of MF. 243

The pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPD) and pigmented purpuric dermatitis-like lesions of MF may have similar histological appearances. In PPD-like MF there may be features typical of MF, but some cases have similar features to PPD. Both PPD and PPD-like MF may have lymphocytes aligned in the basal layer of the epidermis and occasional Civatte bodies. Dermal edema is more common in PPD. Atypia of lymphocytes is seen in MF-like PPD and lymphocytes may be seen in upper levels of the epidermis. 180 PCR studies may show clonal rearrangements of TCR genes in lichenoid forms of PPD, making distinction of some cases from MF difficult. 180

Plaque stage

Patch and plaque stages are part of a progression. In plaques of MF, the infiltrate is more dense and atypical lymphocytes are more common. The lymphocytes measure 10–30 µm in diameter and their nuclei are often obviously indented, ‘prune-like’ or cerebriform. Prominent convolutions are best appreciated in thin sections. Nuclear morphometry of CD3+ T cells has been used as a diagnostic technique to distinguish neoplastic T lymphocytes from reactive ones. 244 It has been suggested that it is not possible to distinguish MF from spongiotic dermatitis based on identifying lymphocyte atypia alone in routine sections. 245

Small collections of cells may aggregate around vessels of the superficial plexus and less often the deep plexus. They also extend round adnexae, particularly pilosebaceous follicles. 246

In addition to lymphocytes, the infiltrate usually contains a small number of eosinophils and sometimes plasma cells. 237 Epidermotropism is still a conspicuous feature. Pautrier microabscesses are seen in more than 50% of biopsies; this proportion increases if step sections are examined. Epidermal changes include parakeratosis, mild psoriasiform hyperplasia, and epidermal mucinosis.237. and 247. Mild spongiosis does not exclude the diagnosis of MF as sometimes claimed, 235 but spongiotic microvesiculation is rare. 248 Spongiotic foci resembling Pautrier microabscesses (pseudo-Pautrier microabscesses) are sometimes seen in spongiotic processes such as allergic contact dermatitis and pityriasis rosea. 249 These foci contain monocyte-like cells, Langerhans cells, and rare lymphocytes. Cell nuclei are pale and less complex than in the component cells of true Pautrier microabscesses. These structures are often vase-shaped and appear to open onto the epidermal surface. They may also be seen in MF.250. and 251. Biopsies of apparently normal skin in patients with plaque stage MF sometimes show a mild superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, often with epidermotropism. 252

Tumor stage

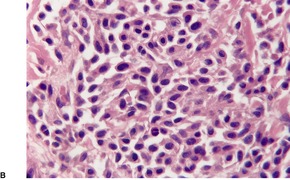

In the tumor stage, the infiltrate has a more monomorphic appearance and is dominated by atypical cells. 253 The proportion of tumor cells relative to reactive cells increases. Mitotic figures are easily seen. The entire dermis is often involved and extension into subcutis may occur. Deep dermal and subcutaneous nodules are particularly likely to occur if electron beam therapy has been given to a pre-existing lesion in the same region. 254 Epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses are uncommon in the tumor stage. Transformation to a diffuse large cell lymphoma may occur. This was defined in one series by the presence of lymphocytes >4 times the size of small lymphocytes in more than 25% of the infiltrate or microscopic nodules of the same. 222 The cells can have variable features and resemble the cells seen in anaplastic large cell lymphoma, or resemble immunoblasts or large pleomorphic cells.

Syringotropism may be the predominant pattern of infiltration with invasion of components of the eccrine coil and duct sometimes associated with proliferation of the epithelial structures. 160

The separation of MF from certain inflammatory dermatoses is not as clear cut as has been suggested. 92 There is often disagreement between pathologists in individual cases. Various attempts have been made to provide diagnostic principles, to weigh the importance of particular features and to standardize reporting of cases.255.256.257.258. and 259. The important histological features in most studies appear to be:

Histology is not useful in predicting disease course. 260

Granulomas are a rare finding in mycosis fungoides (granulomatous MF).248.261.262.263.264.265.266.267.268.269.270. and 271. They are usually small and tuberculoid in type but they may be palisaded and mimic granuloma annulare. 272 At other times the granulomas are poorly formed and consist of small collections of multinucleate histiocytes. The granulomas are more localized than in granulomatous slack skin. Granulomas in MF should be distinguished from small collections of lipidized macrophages (dystrophic xanthomatosis) which are rare findings in the dermis in MF.262.273. and 274. A variant with interstitial lymphoid infiltrates superficially resembling granuloma annulare or inflammatory morphea has been reported,275. and 276. as has generalized granuloma annulare associated with granulomatous MF. 277 Rarely there is extensive fibrosis and mucin in the dermis (fibromucinous variant).248. and 278.

Other rare histological changes include the presence of vasculitis, 279 and the formation of bullae. In the bullous lesions the split may occur at any level. The majority of cases have been subepidermal in location with negative immunofluorescence. 132 Signet-ring cells constituted the infiltrate in one case. 280 In hypopigmented lesions of MF, there is a reduction in melanin in the basal cell layer and, sometimes, melanin incontinence. 124

Epidermal changes such as mild epidermal hyperplasia, dyskeratotic cells, and atypical keratinocytes with large nuclei may be seen following topical treatment with nitrogen mustard. 281

Histological mimics of MF have been reviewed. 282

Immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics

The tumor cells are typically CD3+, CD4+, CD45R0+, and usually CD8−, CD30−.283.284.285. and 286. The cells have the characteristics of mature memory cells of the Th2 subset. 287 There is variable expression of the T-cell markers CD2, CD5, and CD7.

Tumor cells frequently lack expression of CD7.288. and 289. Although this aberrant feature was thought to be specific for a lymphomatous T-cell process and a useful feature in the differential diagnosis of reactive from neoplastic processes, it has been reported in inflammatory conditions.290. and 291. Loss of several T-cell markers is unusual in reactive processes and would favor lymphoma.292. and 293. Loss of the T-cell marker CD62L has also been used as evidence for a neoplastic T-cell proliferation, 294 as has a T-cell proliferation which is CD45RB+, CD45RO−. 295 In the tumor stage there is commonly an aberrant phenotype with loss of T-cell antigens.296.297.298. and 299. Rare cases with similar behavior to classic MF have been reported with a CD4−, CD8+ phenotype or CD4−, CD8–.300.301.302. and 303. Phenotypic shift from CD4+ to CD8+ has been reported. Cases of hypopigmented MF are particularly likely to have a CD8+ phenotype.128. and 129.

Rare CD4−, CD8+ cases are CD56+. 304 Reactive CD8+ cells can also be found in the lesions of MF. 305 Cytotoxic proteins (TIA-1, granzyme B) are sometimes expressed by the CD4+ cells, particularly in late stages of the disease. 292 With progression of the disease some cases may transform to a large cell lymphoma which may be CD30+ (secondary large cell anaplastic lymphoma) or CD30–.219.222.306. and 307. Such CD30+ tumors are not associated with the t(2;5) translocation. 308 Rarely CD30+ cells are found in appreciable numbers in the patch stage of MF. 309 MUM1, a marker for plasma cells, late B cells, and activated T cells, is expressed in transformed CD30+ cells. 310 Expression of certain CD44 splice variants may be linked to systemic spread.311. and 312. In addition to lymphocytes, the dermal infiltrate in MF includes numerous dendritic cells that express CD1a or factor XIIIa.313.314. and 315. The T cells within the epidermis usually express proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Small B lymphocytes are sometimes present in the dermis in small numbers. Rarely neoplastic T cells co-express CD20. 316 Malignant T cells express CCR4 (CC chemokine receptor 4).225. and 271.

In most cases, neoplastic lymphocytes of MF express the αβ TCR but rare cases have been reported in which the γδ receptors are expressed.317. and 318. There are many studies in which the detection of clonal TCR gene rearrangements has been used in the diagnosis of MF, particularly in the early, histologically equivocal lesions of MF.34.288.319.320.321.322.323. and 324. The significance of demonstrable clonal TCR gene rearrangements in suspect lesions remains controversial to a certain extent but most authors agree that such a finding warrants clinical monitoring. Many such cases have progressed to frank MF. 34 TCR analysis from two different sites has high specificity in distinguishing MF from inflammatory dermatoses. 325 Unfortunately, early MF is not uncommonly negative for clonal TCR rearrangements. 230

Expression of the Fli-1 transcription factor is associated with progression to tumor stage MF. 326

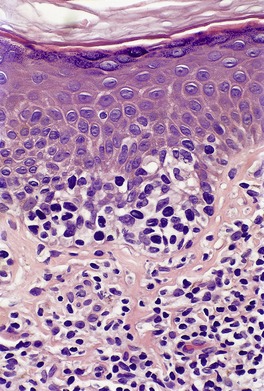

Electron microscopy

There is a great diversity in the morphology of the atypical lymphocytes in MF. The characteristic cell has a highly convoluted (cerebriform) nucleus with heterochromatin located predominantly beneath the nuclear membrane (Fig. 41.3). The cytoplasm contains multivesicular bodies and mitochondria, which are sometimes clumped. Some authors use the term ‘Sézary cell’ for a small to medium-sized lymphocyte with a highly convoluted nucleus and the term ‘mycosis cell’ for a cell which is slightly larger with fewer nuclear indentations.333. and 334. Most authors, however, use the terms, ‘Sézary cell’, ‘mycosis cell’, and ‘Lutzner cell’ interchangeably for the various atypical cells, recognizing that intermediate forms also exist.108. and 335.

|

| Fig. 41.3 Mycosis fungoides. A mycosis cell with its characteristic indented nucleus. (×12 500) |

A much larger cell, sometimes called the ‘pleomorphic cell’, is seen in the tumor stage. It has a vesicular nucleus and a conspicuous nucleolus. 334 The nucleus of the pleomorphic cell may be variably convoluted.

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides

Folliculotropic MF has been classified as a separate entity to classic MF in the WHO/EORTC classification because it has distinctive clinical and histological features, is more resistant to standard therapies, and has a worse prognosis.15.337. and 338.

The term incorporates pilotropic MF, follicular MF, and MF-associated mucinosis. 15 It has also been reported as follicular cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. 339 In this condition, the neoplastic T-cell infiltrate is predominantly folliculocentric and epidermal involvement is absent or minimal.

This form occurs predominantly in adults but there is a broad age range including children. 337 Males are affected more commonly than females. It has been reported in association with lithium therapy. 340

The head and neck are the sites most commonly involved. 338 Lesions range from grouped folliculocentric papules, to plaques and tumors. There is sometimes associated alopecia, cysts, and comedones. It may be associated with nail involvement and ungual mucinosis. 341 Rarely, there is erythroderma or Sézary syndrome.342. and 343. Pruritus is common and may be severe. 337 As a result of follicular mucinosis, there is mucinorrhea in some cases.

The prognosis of this group is generally worse than classic MF. There may be transformation to a CD30+ large cell lymphoma.344. and 345. Spread to extracutaneous sites has also been reported.337. and 346. Sometimes the progress of the lymphoma is rapid. 347 In one large series, the overall survival at 5 years and 10 years was 64% and 14%, respectively. 337 In a recent series, the 10-year survival was 82% and the 15-year survival 41%. 338

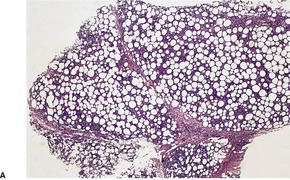

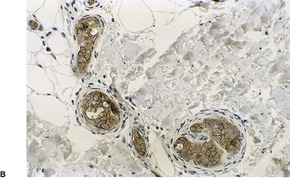

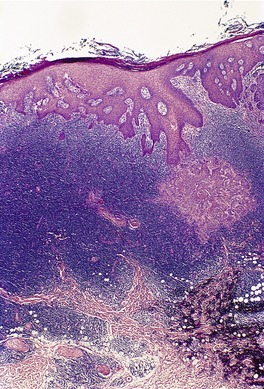

Histopathology337

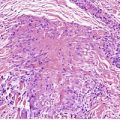

There is a follicular and perifollicular infiltrate of small to medium-sized lymphocytes with or without follicular mucin (Fig. 41.4).348. and 349. The nuclei are often conspicuously cerebriform. The infiltrate may also be present around vessels and the eccrine apparatus, sometimes extending into eccrine epithelium in a similar manner to that in the follicle. Mucin may be minimal or form small pools in the follicular epithelium. This can be highlighted by Alcian blue stains. Pautrier microabscesses are occasionally present. 350 Involvement of the epidermis is not present or is minimal.

|

| Fig. 41.4 Mycosis fungoides-associated follicular mucinosis. (H & E) |

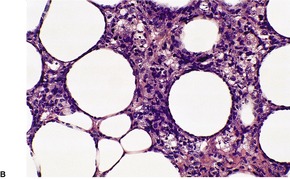

Follicular dilatation and follicular cyst formation may be evident (Fig. 41.5). A granulomatous reaction to ruptured follicular epithelium is seen occasionally.351.352. and 353.

|

|

| Fig. 41.5 Pilotropic (follicular) mycosis fungoides. (A) Dilated follicle with atypical lymphoid infiltrate. (B) There is a follicular infiltrate of cerebriform T cells. (H & E) |

Sometimes there is marked basaloid follicular epithelial hyperplasia, ‘basaloid folliculolymphoid hyperplasia’, 354 or trichilemmal follicular hyperplasia. 355 A similar proliferation of eccrine epithelium is sometimes seen and there is overlap with so-called ‘syringolymphoid hyperplasia’, many cases of which represent a T-cell lymphoma. Inflammatory cells including eosinophils and plasma cells are commonly seen in the infiltrates. 356 Small numbers of B cells are also present; rarely they may be in such number as to mimic a B-cell neoplasm. 357 Sometimes there is an interstitial dermatitis-like pattern. 353

In more advanced cases there may be more confluent infiltration of the dermis and larger atypical cells are more common.

Immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics

The atypical lymphocytes have CD3+, CD4+, CD8− phenotype. Scattered large atypical CD30+ or CD30− cells are commonly seen and they may become more confluent in large cell transformation. It has been suggested that the involvement of hair follicles is related to the overexpression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1(ICAM-1) by keratinocytes in the hair follicle. 358

Pagetoid reticulosis

Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer–Kolopp disease)359. and 360. is a rare distinct variant of MF which presents clinically as large, usually solitary, slow growing, erythematous, scaly or verrucous patches or plaques.361.362. and 363. Lesions are typically found on the distal part of the limbs. It has been described on the penis. 364 Adult males are predominantly affected. Cases in childhood are extremely rare. 365

A prolonged disease-free survival after simple excision or local irradiation is usual. Extracutaneous dissemination has not been reported. 3

Ketron-Goodman disease, which has widely disseminated lesions and a different clinical course, is now regarded as a separate disorder, either a variant of MF or primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma (see p. 987).15.366. and 367.

Histopathology

The epidermis is characteristically infiltrated by large atypical mononuclear cells with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, a large nucleus and prominent nucleolus (Fig. 41.6).368. and 369. Cells are arranged singly or in nests or clusters. This produces a pattern resembling Paget’s disease or melanoma. Atypical cells are present at all levels of the epidermis but are most prominent in the lower third. 361 Cells in the upper layers of the epidermis may show subtle degenerative changes. 368 There are scattered mitotic figures. The epidermis is markedly acanthotic with overlying hyperkeratosis and patchy parakeratosis.

|

| Fig. 41.6 Pagetoid reticulosis. There is marked epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes. (H & E) |

Unlike MF, there are no atypical cells in the dermis, which contains a dense, banal infiltrate of small lymphocytes, histiocytes, and some plasma cells. 368 There are usually no eosinophils.

Immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics

Tumor lymphocytes have a CD3+, CD4+, CD8− or CD3+, CD4−, CD8+ immunophenotype. CD30 is sometimes expressed.362.370.371. and 372. Clonal rearrangements of TCR genes have been demonstrated. This is usually an αβ TCR gene rearrangement but rarely may be an γδ rearrangement.371.373. and 374. Neoplastic cells have been reported to express cutaneous lymphocytic antigen (HECA 452), a skin homing receptor, which might explain the exquisite epidermotropism of this lesion. 371

Granulomatous slack skin

Granulomatous slack skin is a very rare cutaneous lymphoma in which pendulous folds of skin develop in large pre-existing erythematous plaques.377.378.379. and 380. There is predilection for flexural areas, particularly the axilla and groin. 381 There is a clonal infiltrate of CD4+ T cells in the dermis associated with granulomatous inflammation. This condition occurs predominantly in males. 3 Most patients have an indolent course although in a third of patients there is an association with Hodgkin lymphoma.262.377.382. and 383. It may also be associated with classical MF. 380 Another complication reported in 2007, large cell transformation, resulted in the death of the affected child. 384 Recurrence of the pendulous skin folds after surgical excision has been reported. 377 Rarely there is evidence of extracutaneous lymph node involvement. 385

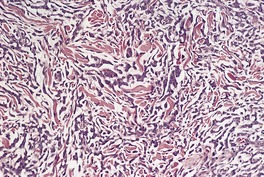

Histopathology377

Early lesions exhibit a superficial, or superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytoid infiltrate, psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, slight spongiosis, parakeratosis, and occasional lymphocytes in the lower half of the epidermis. Occasional multinucleate histiocytes are seen in the dermal infiltrate. In established lesions, there is permeation of the entire dermis and the subcutis by a dense infiltrate of small lymphocytes with convoluted nuclei. Characteristically, there are many multinucleate giant cells scattered uniformly throughout the lymphocytic infiltrate. These giant cells contain large numbers of nuclei. Their cytoplasm may contain lymphocytes and elastic fibers. Cellular infiltrates in the upper dermis may be band-like. The dermis between the cellular aggregates is markedly edematous or fibrotic.

Stains for elastic tissue show a complete absence of elastic fibers from the dermis. Occasionally, calcified elastic fibers are seen.378. and 386. The epidermis is infiltrated by lymphocytes, either singly or in small clusters in a pattern similar to the patch or plaque stage of MF.

Immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics

The small lymphoid cells are CD3+, CD4+ T cells. The multinucleate cells express histiocyte markers such as CD68.387. and 388. Rarely, large CD30+ cells are part of the infiltrate. 389 The neoplastic cells are generally αβ T lymphocytes and clonal TCR rearrangements of the β-chain have been demonstrated.379.386. and 390. Occasional cases demonstrate a clonal γ-chain rearrangement, 385 or do not demonstrate a clonal rearrangement. 391 A translocation t(3;9)(q12;24) has been demonstrated in one case. 392

SÉZARY SYNDROME

Sézary syndrome (SS) is an uncommon form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In the United States, the incidence is in the vicinity of 0.3 per 106 persons. 57 In the current WHO/EORTC classification it is designated as an entity distinct from mycosis fungoides, although some would regard it as a manifestation of mycosis fungoides, 393 or a leukemic stage of mycosis fungoides. 394

The International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) recognizes several variants of erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, erythroderma being defined as diffuse erythema involving 80% of the skin surface. Within this spectrum is SS which may arise de novo or following mycosis fungoides, erythrodermic mycosis fungoides which lacks the hematologic findings of SS, and erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. 190

Sézary syndrome was defined historically by the triad of erythroderma, lymphadenopathy, and circulating atypical mononuclear cells in the peripheral blood. 395 Lymphadenopathy, although common in SS, is no longer considered requisite for the diagnosis.

The circulating atypical T cells with hyperconvoluted ‘cerebriform’ nuclei (a nuclear contour index of 6.5 or more) have been called ‘Sézary’ or ‘Lutzner’ cells: there are small and large variants. 393 They can be recognized in blood films stained by the Giemsa or Wright methods but cell counts using smears may underestimate numbers. 396 These cells are not specific for SS and may be seen in small numbers in other cutaneous inflammatory conditions and in normal blood. 190

The ISCL defines SS as generalized erythroderma with hematologic criteria which include: an absolute Sézary cell count of at least 1000 cells/mm3; a CD4/CD8 ratio of 10 or more; aberrant expression of pan T-cell markers CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5; increased lymphocyte counts with evidence of T-cell clonality in the blood and a chromosomally abnormal T-cell clone. 190

Russell-Jones has developed an algorithm for the diagnostic separation of erythrodermic T-cell lymphoma and non-neoplastic causes of erythroderma. 397

Less constant clinical features include cutaneous edema, alopecia, nail dystrophy, and palmar and plantar keratoderma. 398 Rarely bullous lesions, 399 plane xanthomas, 400 vitiligo, 401 leukoderma, 402 or a monoclonal gammopathy403 may develop. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is present in many cases.55. and 404. Increased blood immunoglobulin levels are also common. 405

Prognostic parameters are still being investigated, but visceral involvement, advanced age, long interval before diagnosis, previous history of mycosis fungoides, and circulating Sézary cell counts of more than 5% of the total lymphocyte count, and the presence of the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) genome in keratinocytes are unfavorable prognostic features.394.406. and 407. In one series the 5-year survival was 33.5%. 406 Death is frequently due to systemic opportunistic infections as a result of immunosuppression. 408

Sézary syndrome usually develops in late adult life. Cases in childhood are extremely rare. 409 It may be preceded by another chronic inflammatory dermatosis such as atopic dermatitis. 410 One recent study found no causal relationship between atopy and SS or MF, however. 411 It has been reported in association with infliximab therapy, 412 and following exposure to ionizing radiation. 413 Development of typical lesions of mycosis fungoides has been reported after remission of primary SS, 414 and secondary SS may follow folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. 415 Large cell transformation in skin, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood has also been reported.416. and 417. There is an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, Hodgkin lymphoma, and internal malignancies in patients with SS.175.418. and 419.

Some cases of erythroderma have demonstrable T-cell clones in blood without fulfilling the criteria for SS or erythrodermic MF. 420

Histopathology400.421.422. and 423.

There is great variability in the histological findings. In many cases they are similar to those in MF.3. and 424. The same problems of specificity apply as with the early stages of mycosis fungoides discussed above. In up to 40% of cases, however, the biopsy appearances are non-diagnostic.425. and 426. Multiple biopsies may be more successful in obtaining a histological diagnosis of SS. Topical and other therapy often mask or obliterate diagnostic changes. Non-specific histological findings are common in SS even when a circulating T-cell clone is present in blood. 427 In one author’s experience, the diagnosis of SS could be established with greater certainty by hematologic studies rather than by skin biopsies. 426

In the most frequently observed histological patterns in SS, there is a perivascular or less often a band-like cellular infiltrate involving the papillary dermis and sometimes the upper reticular dermis as well. 422 Epidermotropism is present in some of these cases and Pautrier abscesses may be found, particularly if multiple sections are examined. 422 In one recent series epidermotropism was minimal or absent in 61% of cases. 423 The infiltrate is of varying density and is composed of small lymphocytes admixed with some larger cells with indented or cerebriform nuclei. Lymphocytic cellular atypia may be minimal or inapparent. 423 Atypical lymphocytes can be seen in spongiotic processes, 56 and some fixation protocols can produce apparent nuclear atypia. 423 The use of ultrathin sections enhances the detection of these cells. The cellular infiltrate is present in a background of variable epidermal changes, which include irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with orthokeratosis and focal parakeratosis. Spongiosis is sometimes present although usually mild. 421 The papillary dermis is fibrotic with thickened collagen bundles and scattered melanophages. Eosinophils and plasma cells may be found in small numbers. Prominent ectasia of papillary dermal vessels is present in many cases and is more pronounced than in patch/plaque lesions of MF. 428

Rarely, non-caseating granulomas may be seen in the dermal infiltrate, sometimes after therapy. 429

Immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics

The neoplastic lymphocytes in the skin and blood are CD3+, CD4+, CD45RO+, CD8−, CD30−, and frequently CD2−, CD7−. Studies employing double staining for CD4/CD8 ratios >10 in skin biopsies have been deemed unhelpful in making a diagnosis. 430 Circulating clonal CD4+ T cells have been shown to express the skin and lymph node-homing chemokine receptors CCR4, CCR10, and CCR7. Clonal TCR gene rearrangements are present in most cases and are critical if histology and immunohistochemistry are unhelpful. Analysis for TCR gene rearrangements either by PCR426 or Southern blot techniques may be difficult to perform in skin biopsies because of the small number of cells in the infiltrate and problems in extracting cells from skin. Demonstration of clonality in circulating T cells in the peripheral blood aids in the differentiation of SS from other non-neoplastic forms of erythroderma. 431 The presence of the same T-cell clone in skin and blood is strong evidence of SS in the absence of diagnostic histological changes.432. and 433. Flow cytometric counts of CD4+/CD7− cells in peripheral blood have shown a significant correlation with the number of circulating Sézary cells. 434 In some cases, however, the cells are CD4+/CD7+ which obscures the phenotypic distinction between neoplastic and normal T cells.406. and 435. Diminished expression of CD3 and lack of CD26 expression have been used to detect and enumerate atypical cells in the blood in SS.435.436. and 437.

A case of Sézary syndrome-like erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma with a CD8+, CD56+ type phenotype has been described. 438

Electron microscopy

The Sézary cells have a convoluted nucleus with deep and narrow indentations. The cytoplasm has a number of fibrils. Ultrastructural morphometry has been used to distinguish Sézary cells in the blood from normal and reactive lymphocytes although this technique is rarely used in routine practice. 441

ADULT T-CELL LEUKEMIA/LYMPHOMA

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) is a T-cell lymphoma resulting from infection with human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), a type C retrovirus.442.443. and 444.

The virus is endemic in south-western Japan and the Caribbean as well as certain parts of South America and Africa. It has also been reported sporadically in parts of Europe and the south-eastern USA.445.446.447.448. and 449. HTLV-1 is transmitted by sexual contact, breastfeeding, infected blood products, and percutaneously.445. and 448. Familial clustering has been described. 449 The average age of onset of ATLL in a large series from Japan was 57 years (24–92 years). 450 It is very rare in children. Immigrant studies suggest there is a long latent period from viral infection to overt ATLL. 451

Several clinical forms are recognized; they have been divided into four groups by Shimoyama: 450 (1) an aggressive acute form seen in approximately 65% of patients and associated with a very high white-cell count, hepatosplenomegaly, hypercalcemia, and lytic bone lesions; (2) a chronic form associated with lower white-cell counts and no hypercalcemia. Lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly may be present as well as skin manifestations; (3) a smoldering form with normal lymphocyte counts in blood but with 1–5% ATLL cells. Skin and lung infiltrates may be present; (4) a lymphomatous form with no lymphocytosis, less than 1% circulating ATLL cells and isolated lymphadenopathy or extranodal tumors. A purely cutaneous form which resembles MF has also been described.450. and 452. The integration pattern of HTLV-1 proviral DNA may be the explanation for the heterogeneity in the behavior of ATLL.453. and 454.

Skin manifestations are often the initial manifestation of ATLL (50–70% of cases); they are found in all forms of the disease.455. and 456. Lesions are often widespread and have many forms including erythematous patches, plaques, papules, and tumors. Erythroderma and vesiculobullous and purpuric eruptions are less common cutaneous manifestations.457.458. and 459. Presentation as an isolated single skin nodule is very uncommon. 460 Non-specific skin lesions or prurigo may precede the onset of acute ATLL.461. and 462.

The prognosis depends on the clinical subtype; it is worse in the acute and lymphomatous variants with survival of 2 weeks to 1 year. 15

Atypical lymphocytes are found in the blood in 50–80% of patients at presentation; virtually all develop a leukemic phase eventually. 463

Histopathology

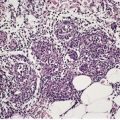

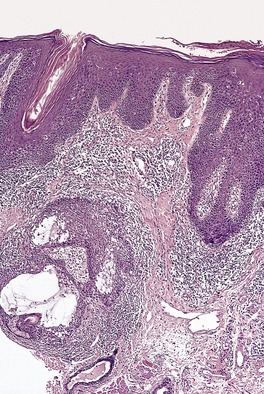

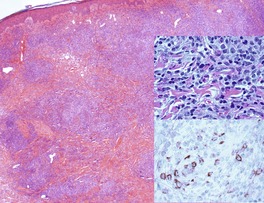

The cutaneous lesions of ATLL share some features with MF in having an infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes in the upper dermis with variable epidermotropism and occasional Pautrier microabscesses. Unlike MF, these microabscesses may contain prominent apoptotic fragments (Fig. 41.7). In the nodule and tumor stage the dermal infiltrate is more extensive, confluent and atypical and can extend into the subcutis. As in the tumor stage of MF, epidermotropism is less apparent. 457 In some cases the infiltrate conforms to a papular outline, an uncommon pattern in MF. 103

|

| Fig. 41.7 Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. There is extensive epidermotropism with Pautrier microabscess formation. Characteristic apoptotic debris is just visible. (H & E) (Case kindly supplied by Dr Tetsunori Kimura, Section of Dermatology, Sapporo General Hospital, Sapporo, Japan) |

The infiltrating cells may be medium to large size, sometimes with pleomorphic or polylobated nuclei.445. and 455. Other elements, such as small lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells, are less common than in MF. Sometimes dermal aggregates form, resembling granulomas.464. and 465.

Atypical lymphocytes are sometimes seen in the lumina of blood vessels in the dermis. Angiocentric and angiodestructive lesions are rare manifestations of ATLL. 456

Immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics

The neoplastic cells are T lymphocytes exhibiting clonal TCR rearrangements. They are usually CD2+, CD3+, and CD4+. Rarely, the cells express a CD4+, CD8+466 or CD4−, CD8− phenotype. 459 They also express CD25, which is a distinguishing feature between ATLL and Sézary syndrome.467. and 468. HTLV-1 is clonally integrated in T cells in all cases and can be demonstrated in paraffin-embedded tissue. 469

Electron microscopy455

The tumor cells show slight to marked nuclear irregularity with a convoluted shape and a speckled chromatin pattern. The circulating lymphocytes have been termed ‘flower cells’. 449 The degree of nuclear indentation is much less than in the cells of MF and SS. The cells in ATLL have lysosomal granules and glycogen in their cytoplasm.

PRIMARY CUTANEOUS CD30+ LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDERS

The primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders are linked by the common histological feature of large atypical lymphoid cells expressing CD30. 3 CD30 is a 120 kDa transmembrane cytokine receptor to the tumor necrosis factor receptor family and is preferentially expressed by activated lymphoid cells.

As well as the conditions discussed here, CD30 labels large proliferating T- and B-cell blasts in reactive lymphoid tissue,220. and 471. Reed–Sternberg cells and variants in classical Hodgkin lymphoma, proliferating cells of other B- and T-cell lymphomas, and other non-lymphoid neoplasms such as embryonal carcinoma. 471

The primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders include: primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL), lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP), and cases which do not fit clearly into these categories, borderline cases. Distinction between C-ALCL and LyP is not always possible on the basis of histological criteria and classification is based on clinical presentation and course as well as the histological appearance of lesions. Borderline cases are those that do not fit either classification; clinical follow-up may allow assignment to the appropriate group. 472 The Notch signaling pathway may play a role in the pathogenesis of this group of disorders. 473

Primary systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma involves both lymph nodes and extranodal sites. The skin is commonly involved (21% of cases). Although skin lesions have identical morphology to those in C-ALCL, this form involves a different age group and has a different prognosis. Up to 85% of these tumors express anaplastic large cell lymphoma kinase protein (ALK). In most cases this results from the translocation t(2;5) in which part of the nucleophosmin (NPM) gene on chromosome 5 is juxtaposed to part of the ALK locus on chromosome 2 resulting in expression of the chimeric oncogenic tyrosine kinase NPM-ALK. The ALK-1 antibody is directed to the cytoplasmic portion of the ALK protein. 474 In 15–20% of cases expressing ALK there is a variant translocation and not the t(2;5) translocation. 475 It is discussed further later.

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma

This form of lymphoma represented 9% of primary cutaneous lymphomas in the EORTC series. 3 This lymphoma occurs predominantly in older adults (median age of 60 years), and is rare in children and adolescents.476. and 477. There is a male preponderance. 478 Most patients have solitary or localized papules, nodules, and tumors which are red to violaceous in color and often ulcerated. Some single lesions resemble keratoacanthoma. 479 Single lesions may arise in uncommon sites such as the penis. 480 Partial or complete spontaneous regression occurs in up to 25% of cases. 481 This may be related to interactions of CD30 and its ligand (CD30L) and death receptor mediated apoptosis.482. and 483. Cases previously reported as regressing atypical histiocytosis represent this form of ALCL.484. and 485. A transient lesion has been reported associated with cyclosporine (ciclosporin) therapy. 486 Cases of C-ALCL demonstrate abnormal expression of the activator protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factor JUN. 487

The prognosis is very good but occasionally there are cases which disseminate in the skin and spread to involve lymph nodes and other sites, and these have a poorer prognosis.488.489. and 490. In one series, disease-specific survival for localized versus generalized disease was 91% and 50%, respectively. 489 Patients with multifocal disease are more likely to develop extracutaneous disease.488. and 491.

C-ALCL has been reported in association with atopic eczema, 492 psoriasis,493. and 494. internal malignancies,495. and 496. and B-cell lymphomas.497. and 498. It may also arise after solid organ transplantation.159.165.499.500.501.502. and 503. In very rare cases CD30+ circulating cells can be detected in the blood. 504

C-ALCL can arise in patients with previous LyP. In this situation it is difficult to distinguish it from histological type C LyP. It behaves like conventional C-ALCL in this situation and has a good prognosis. 505 It has been reported in patients with concurrent patch stage MF, 506 and in patients who develop LyP after C-ALCL. 507 LyP, MF, and C-ALCL appear to be clonally related in such patients.508. and 509.

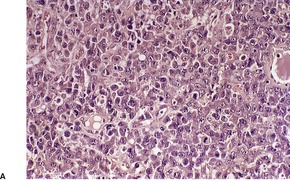

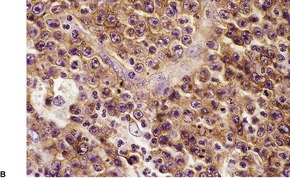

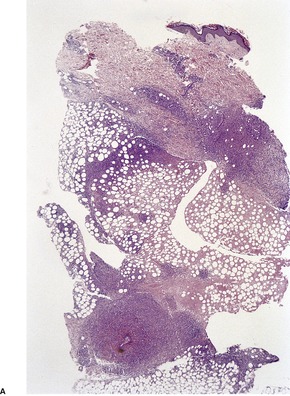

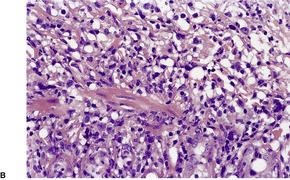

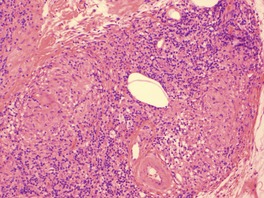

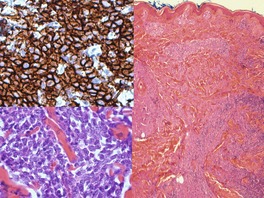

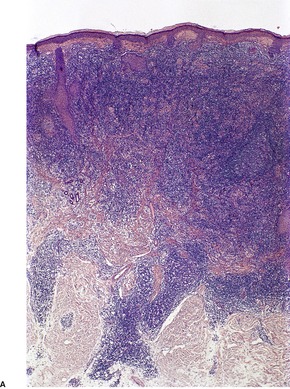

Histopathology510

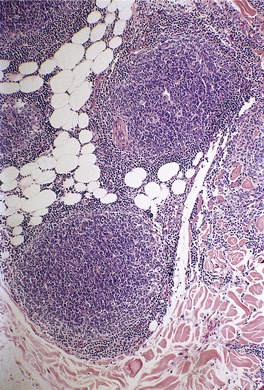

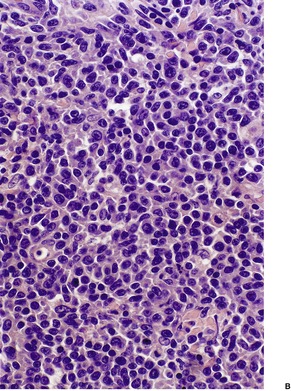

There is an infiltrate in the dermis and sometimes the subcutis which typically consists of confluent sheets of large, CD30+ cells (Fig. 41.8). The majority of these cells are typical anaplastic cells with round, oval, or indented nuclei (‘hallmark’ or ‘buttock’ cells), prominent nucleoli, and copious cytoplasm. In some cases the cells are more pleomorphic or immunoblastic in appearance. Some cells resemble Reed–Sternberg cells. A small cell variant with intermediate-sized atypical cells has also been described. 511 Cell type does not appear to affect prognosis. 488 There may be a significant component of small lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and histiocytes which in some cases may obscure the neoplastic cells. 510 This is most prominent in the lymphohistiocytic and neutrophil-rich variants. 512 The epidermis is not infiltrated by tumor cells but there is often ulceration. Rare cases have a ‘signet-ring’-like morphology. 510 In some cases there is considerable epidermal hyperplasia. 479 Epidermotropism, tumor necrosis, vascular invasion and destruction, and nerve involvement are also present in some cases. 510 Xanthomatous change may be seen after radiation therapy. 513

|

|

| Fig. 41.8 (A) Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. (H & E) (B) Many cells exhibit a positive Golgi zone. (Immunoperoxidase stain for CD30) |

Immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics

More than 75% of the neoplastic cells are CD30+. 478 The majority are CD3+, CD4+, CD8−. A small number of cases are CD8+.15. and 514. Most but not all are EMA− and ALK−. 220,515 The presence of a positive reaction for ALK generally indicates cutaneous spread of primary systemic ALCL rather than C-ALCL. 516 Rare cases showing a positive cytoplasmic reaction for ALK without the usual t(2;5) translocation or variant translocations have been reported. 517 Positive reactions for CD15 in a cytoplasmic and Golgi zone pattern have been reported in a small number of cases. 505 Cells may express cytotoxic markers TIA-1, and granzyme B as well as CD56.518.519. and 520. Neoplastic cells may express the cutaneous lymphocyte antigen HECA 452 which is not usually expressed in primary systemic ALCL. 521 They also express MUM1. 310 In the vast majority of cases, the cells do not express EBV by PCR or in-situ hybridization.483.515. and 522.

The majority of cases are of T-cell type and exhibit clonal β or γ TCR gene rearrangements. 523 Atypical cells lack the t(2;5) translocation except in rare cases.524. and 525.

Clusterin expression, a marker for systemic anaplastic large cell lymphomas, can also be expressed by C-ALCL.526. and 527. Cells also express the cytokines CCR3 and CCR4,490. and 528. and the cell surface adhesion molecule CD44.529. and 530. CD95 (APO-1/Fas) is strongly expressed in C-ALCL and LyP and may play a role in regression of lesions. 531

Lymphomatoid papulosis

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is a chronic lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by the appearance of crops of papules, nodules, and sometimes large plaques at different stages of development. Lesions spontaneously regress after several weeks or months, sometimes resulting in atrophic scars. The clinical course may extend over decades. Initially, the lesions are smooth but later they become necrotic, crusted, and ulcerated.532.533.534.535.536.537. and 538. There may be only a few lesions, or many hundreds present during each exacerbation. 347 They occur mainly on the trunk and proximal parts of the limbs, but may also arise on the face, scalp, palms, and soles. Lesions rarely involve mucosal surfaces. 539 There is a predilection for females in the third and fourth decades of life. LyP also occurs in children.540.541. and 542. Rare clinical presentations include pustular lesions, 543 localized (agminated) lesions,544. and 545. lesions with a white halo, 546 and a pattern resembling hydroa vacciniforme. 547 It has been associated with the hypereosinophilic syndrome,548.549. and 550. atopic dermatitis treated with cyclosporine, 551 and parathyroid nodular hyperplasia. 552 Lesions in pregnant women may regress after delivery. 553 Keratoacanthoma has also been reported in association with LyP.554. and 555.

There is an increased frequency of prior, coexisting or subsequent lymphoproliferative disorders associated with LyP: this is most commonly mycosis fungoides or Hodgkin lymphoma.556.557.558.559.560. and 561. It has been claimed that in approximately 5–10% of cases, there is progression to a malignant lymphoma (Hodgkin lymphoma, MF, ALCL) or myeloproliferative disorder.347.373.556.562.563.564.565.566.567.568.569.570.571.572.573. and 574. Subsequent neoplasms may demonstrate identical clonal TCR gene rearrangements to those in LyP.561. and 575.

In a study of LyP associated with MF, LyP preceded MF in 67% of cases, followed MF in 19% of cases, and occurred concurrently in 14% of cases. 576

Clonal T cells similar to those in skin lesions have been rarely identified in bone marrow and blood.577. and 578.

LyP has an excellent prognosis. In a study of 70 patients by the EORTC group, no patient died of malignant lymphoma and the 5-year survival was 100%. Similar survival figures were reported in another series. 489

LyP is not associated with EBV579 or human herpesvirus type 6 and 7, but a recent study reports an association of LyP with human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8).515.580.581. and 582.

The histological appearance of LyP suggests it is a lymphomatous process and most would now regard this condition as a low-grade cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, part of a spectrum with C-ALCL. 583 Some still classify LyP as a ‘pseudolymphoma’. 584 Several studies have identified a clonal population of T cells in 60% of the lesions in LyP,535.585.586. and 587. but a clonal population is not always identified. 509 In a recent study, a clonal population was found in only 22% of archival cases of LyP by PCR. 523 Single cell analysis of CD30+ cells in one study found a single T-cell clone in all cases including anatomically and temporally separated lesions; CD30− background cells were polyclonal. 588

Because the histopathological and immunophenotypic features of LyP overlap with C-ALCL, the clinical appearance and course are important features in separating the two conditions and choosing treatment options. 3 Lesions of C-ALCL tend to be few and localized whereas LyP presents as recurring crops of multiple, widely dispersed lesions which involute spontaneously. Some cases have overlapping features and are classified as ‘borderline’. Spontaneous regression can occur in both LyP and C-ALCL. Borderline cases with follow-up may ultimately be classified as LyP or C-ALCL but overall have a favorable prognosis. 589 It has been suggested that in LyP, cell-mediated immune reactions involving the small lymphocytes may play a role in the spontaneous regression of lesions. 590

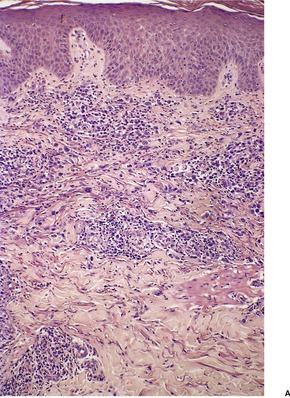

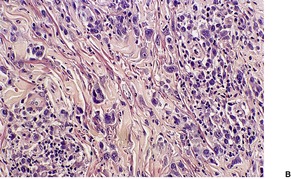

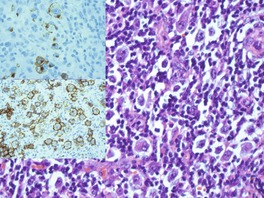

Histopathology591

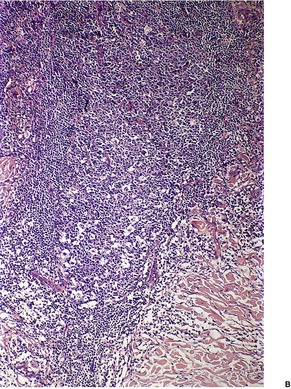

The appearance of the lesions varies to a certain extent according to their age. There are three overlapping histopathological subtypes of LyP: types A, B, and C. 3

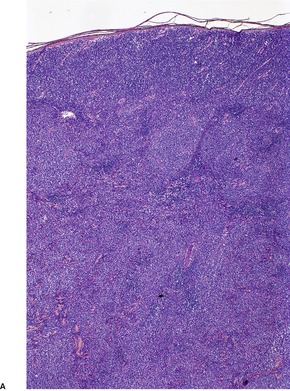

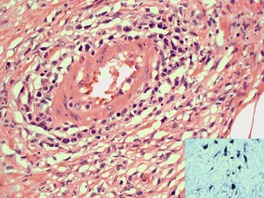

LyP type A is characterized by a wedge-shaped, mixed cellular dermal infiltrate which includes a variable number of large atypical cells similar to those in C-ALCL (Fig. 41.9). They may be multinucleate or resemble Reed–Sternberg cells. There is a background population of small lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and histiocytes. Epidermotropism is variable but usually not prominent.

|

|

| Fig. 41.9 Lymphomatoid papulosis. (A) Type A histology. (B) There is a mixture of large atypical cells and small lymphocytes. (H & E) |

LyP type B is an uncommon pattern seen in 10% of cases. 15 It is characterized by a perivascular or band-like dermal infiltrate with epidermotropism. The predominant cell types are small to medium-sized lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei. This picture resembles plaque stage MF and separation from MF may require clinical correlation. Large CD30+ cells seen in the other two forms are uncommon. Some lesions have overlap features of these two types. Different lesions in the same crop may show either of these patterns. 591

LyP type C lesions resemble C-ALCL and have a monotonous population of large atypical cells with relatively few admixed inflammatory cells.

Lesions in any of the subtypes may have focal spongiosis in the epidermis, parakeratosis with neutrophils, and ulceration. Epidermal hyperplasia is present in some cases. 592 Mitotic figures are common in all histological subtypes. There is some dermal fibrosis in resolving lesions, particularly in those that have ulcerated. There may be only a few atypical cells in late lesions. CD1a+ dendritic cells may be a conspicuous component of the cellular infiltrate. 593

A rare variant has been described in which the infiltrate is centered around hair follicles.594.595. and 596. Other variant patterns include a syringotropic pattern, LyP with epidermal vesicles, LyP with follicular mucinosis, 591 LyP with prominent myxoid change, 597 and LyP with angionecrosis. 598

Immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics

The large atypical cells in LyP types A and C are CD30+, CD3+, CD2+/−, CD4+/−, CD8− similar to the large cells in C-ALCL. Rare cases are CD8+.599. and 600. Cells are generally negative for CD15 and EMA but positive reactions have been reported in a few cases, the former having a cytoplasmic and Golgi zone pattern. 505 As in C-ALCL, the CD30+ cells may express cytotoxic markers TIA-1, perforin and granzyme B, and CD56;518.600.601.602. and 603. they are ALK−.518. and 601.

The atypical cells in the type B lesions are CD3+, CD4+, CD8−. Despite some reports, CD30+ cells may be present in this subtype and overlap cases with type A histology occur.15. and 591. The CD30+ cells may co-express CD134. 604

MUM1 (multiple myeloma oncogene 1) is expressed in the large cells in types A and C. 310 In one study, it was found that there was positive staining for MUM1 in 85% of cases of LyP but only in 20% of cases of primary C-ALCL. It was suggested that this was a useful marker is distinguishing between these two conditions. 605 Tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factor 1 (TRAF1) has similarly been shown to be useful in distinguishing between LyP and C-ALCL, being expressed in 84% of the former and only in 7% of cases of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, primary and secondary. 606

SUBCUTANEOUS PANNICULITIS-LIKE T-CELL LYMPHOMA

The current WHO/EORTC classification confines this condition to those T-cell lymphomas which have a panniculitis-like histology and have an αβ+ T-cell phenotype. This group previously included lymphomas with a γδ phenotype. The latter group, which exhibits important differences in histology and behavior, is now classified separately as cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (provisional) in primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified, of the WHO/EORTC classification. 15 Most of the earlier literature does not distinguish between these two groups.608.609.610. and 611. Other lymphomas can also involve the subcutis to varying degree. 611

Most if not all cases of so-called cytophagic histiocytic panniculitis (see p. 466) in the older literature, particularly the indolent forms, are not inflammatory but subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL).608. and 609.