CHAPTER 3 Cross-sectional Imaging of the Hip

CROSS-SECTIONAL IMAGING MODALITIES

With both imaging modalities, there are additional considerations to keep in mind, such as contrast administration. Contrast-enhanced examinations with intravenously administered contrast agents are typically reserved for evaluation for infection, inflammatory arthropathies, neoplasms, and vascular lesions.1–4 Rarely, a contrast-enhanced multidetector CT scan should be performed over MRI for the aforementioned indications. In addition, direct MR arthrography and CT arthrography (which involve direct administration of contrast material into the joint) can be used to better evaluate small intra-articular bodies and cartilaginous structures such as the labrum or articular cartilage. Indirect MR arthrography (intravenous administration of contrast material, which readily accumulates in the joint after a short delay) can be used in similar situations. This method cannot, however, achieve adequate joint distention with indirect arthrography in the absence of a preexisting joint effusion. For this reason, we reserve indirect arthrography of the hip for suspected labral tears when a direct arthrogram is logistically impractical and for some postoperative indications. The radiologist generally should have a role in deciding which study is most appropriate before imaging, but intra-articular or intravenous contrast administration often requires an order or prescription from the referring clinician.

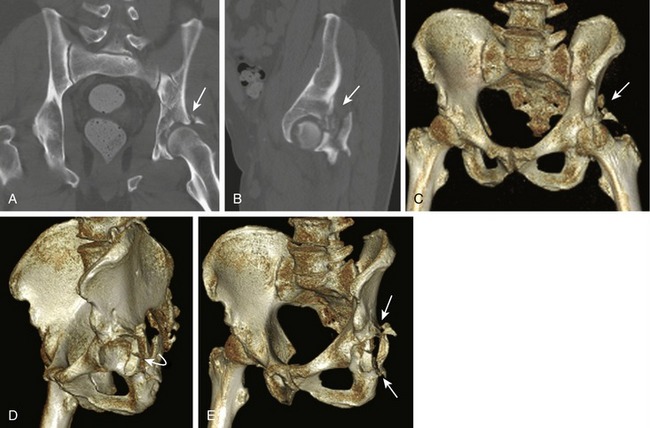

Although interpretation of cross-sectional imaging studies of the hip might be best left to the radiologist, orthopedists and emergency medicine clinicians frequently find themselves in a setting where they must provide a preliminary interpretation of CT or MRI examinations. With multidetector CT, identifying pathology reliably on a quality study can be easy for someone comfortable with plain x-ray interpretation; getting interpretable images is the most difficult part. All of the information from the multidetector CT is on one series of axial images, although additional reformatting of this information in coronal and sagittal planes and three-dimensional models can be helpful in confirming pathology. Software applications allowing for accurate three-dimensional reformats are useful in the setting of articular fractures to help quantify the percentage of surface area involvement (Fig. 3-1).

Interpretation of MRI sequences can be more daunting. For even the most basic interpretations, each MRI sequence must be categorized as fluid-sensitive or fat-sensitive. Fluid-sensitive sequences include all T2-weighted sequences and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences. On these images, all fluids (including water, blood, and edema) are bright, or hyperintense. On fat-sensitive T1-weighted sequences, fluid is dark, but normal bone marrow is bright. With these images, loss of the normal hyperintense bone marrow signal often leads to identification of pathology. When the interpreter is confident about this categorization of the MRI sequences available, basic and preliminary interpretation of pathologies such as fracture and joint effusion is possible for clinicians who have an understanding of the pathologies themselves.5

INJURY-SPECIFIC IMAGING

Occult Hip Fracture

In the setting of a radiographic examination that is equivocal for hip fracture or negative for fracture but accompanied by a persistent high clinical suspicion for occult fracture, MRI and multidetector CT can be used for further assessment. In our opinion, which is supported by radiology literature, MRI is the imaging study of choice to exclude occult hip fracture. Even a limited, 15-minute MRI protocol is nearly 100% sensitive for occult hip fracture if it is a fluid-sensitive (STIR or T2-weighted fat-suppressed) sequence. In cases of fracture, both of these sequences show hyperintense (bright) bone marrow edema surrounding the fracture site, and an accompanying T1-weighted sequence can be used for description and classification of the fracture using the hypointense (dark) fracture line (Fig. 3-2).6–9

In difficult cases of subtle nondisplaced fracture in an osteopenic patient, the edema on MRI that alerts the radiologist to fracture is not visible on CT. Similarly, subtle stress fractures of the femoral neck, acetabulum, pubic symphysis, and sacrum are common and are best evaluated by MRI for the same reason. Subcapital proximal femur fractures are particularly difficult to diagnose on CT and on conventional radiographic series. MRI of the hip or of the entire pelvis is the standard of care in these cases when there is discordance between physical examination findings and radiographs or CT, or when CT and radiographic studies are equivocal for fracture. Even so, a multidetector CT examination identifies most hip fractures and is a reasonable option to try, especially when the patient is already undergoing CT scanning as part of a trauma workup. If the CT scan is negative but the clinical suspicion for proximal femoral fracture persists, MRI is indicated. In contrast, if even a mediocre-quality MRI examination is negative for hip fracture, there is no acute or subacute hip fracture.10

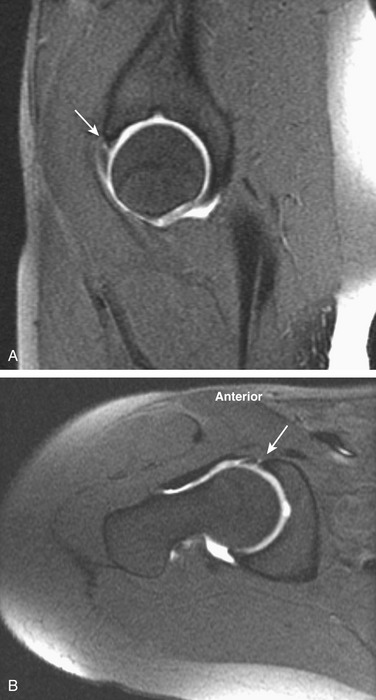

Acetabular Labral Tears

The preferred technique for imaging the acetabular labrum is direct MR arthrography. Labral tears are diagnosed by identifying paramagnetic contrast material (which is white on most MRI sequences) that undermines or outlines the labral defect or extends directly into the labrum substance (which is normally black on MRI sequences) (Fig. 3-3). Smaller, undersurface tears can be differentiated from normal variations such as sublabral recesses (which are currently a subject of controversy in the radiology literature), by their location and by the configuration of the defect. In younger patients with little joint wear and tear, the normal anterior and superior labrum should be sharply defined; it should be triangular and hypointense on all sequences. There is no recess anteriorly, so a defect in the undersurface of the anterior labrum which alters its triangular morphology should be considered a tear. Signal alteration within the labrum (especially fluid bright defects or findings into which contrast material readily flows) should also raise strong suspicion of a tear.