Men of all races are currently more open to requesting and undergoing treatments for a plethora of cosmetic concerns. Among the most common goals are procedures that combat the signs of aging, rejuvenate the skin, even out the color tone, address textural issues such as acne scarring, and improve hair disorders. Given the differences in cultural ideals and anatomic/physiologic differences in ethnic skin, it is important for physicians to be aware and sensitive to the nuances required when providing consultation and treating non-Caucasian men. The main cosmetic concerns of this patient cohort and their optimal management are presented.

Key points

- •

Cultural, pathophysiologic, and anatomic differences in ethnic skin require different treatment approaches than those offered to fair skinned patients.

- •

Hyperpigmentation and scarring are the most prevalent adverse effects that limit the use of certain treatment modalities such as laser/light therapies.

- •

Sun protection is imperative for prevention and maintenance of treatment results in ethnic men.

Introduction

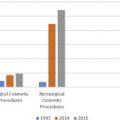

The demand for cosmetic procedures is on the increase in the male population of all ethnic groups. According to the latest statistics from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, more than 1,000,000 cosmetic procedures (both invasive and minimally invasive) were performed in men in 2015, and 25% of the individuals undergoing treatments were men of color. Although no standard classification system exists for skin of color, it is common for physicians to use the Fitzpatrick skin types categories, originally developed to describe the response to UV light in phototherapy. Using the Fitzpatrick system, olive/beige tones are classified as type IV, brown skin as type V, and black skin as type VI. In the United States, people from Africa, the Caribbean, Asia, Pacific Islands, Latin America, Native Americans, Latino, Hispanics, Indians, and those of Middle Eastern origin are considered to have ethnic skin.

There is a the paucity of clinical data and studies specifically examining cosmetic concerns in ethnic men, given that this is a growing population with distinct needs regarding gender and skin physiology, it is important for dermatologists to be aware how to treat, counsel, and address the needs of this patient cohort. In fact, a survey conducted in dermatologists in Australia showed that 85% of participants were not confident in managing common cosmetic issues in skin of color, and more than 80% stated they would have liked more teaching in skin of color.

The skin pathophysiology in ethnic individuals has biological differences when compared with fair skin that affect cosmetic treatment needs. Because of the increased melanin, patients with darker skin have inherent protection against extrinsic factors of aging such as damage from UV, and photoaging appears decades later compared with those with lighter skin tones. Photodamage is typically manifested as pigmentary aberrations (lentigines, macules, melasma) rather than rhytides. Moreover, facial aging in patients of color is due to volume loss from deeper muscular layers than dermal layers. Perioral and periorbital lines may not occur as early in patients of color, but there is a tendency toward mid and lower face aging, with manifestations including the formation of nasolabial folds and sagging of the jowl. Skin of patients of color also have thicker more compact dermis and stratum corneum with more cornified layers.

Hair structure is also different in patients of color patients. Black individuals have flat elliptical-shaped hair shafts with curved hair follicles, and fewer elastic fibers anchoring hair follicles to the dermis, whereas the Asian hair shaft is round with the largest cross-sectional area.

Aside from the differences in skin pathophysiology and anatomy in patients of color, there are profound cultural differences that dictate cosmetic concerns, habits, and goals. Ethnic men have historically been hesitant to pursue cosmetic treatments because of fears of being viewed as rejecting their racial identity. As techniques have advanced, and physicians have developed a nuanced and culturally/gender-sensitive approach to beauty, ethnic men can now share cosmetic goals similar to their Caucasian counterpart men. Enhancing physical appearance and combating aging is a shared goal because it is tied to personal success in life.

Introduction

The demand for cosmetic procedures is on the increase in the male population of all ethnic groups. According to the latest statistics from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, more than 1,000,000 cosmetic procedures (both invasive and minimally invasive) were performed in men in 2015, and 25% of the individuals undergoing treatments were men of color. Although no standard classification system exists for skin of color, it is common for physicians to use the Fitzpatrick skin types categories, originally developed to describe the response to UV light in phototherapy. Using the Fitzpatrick system, olive/beige tones are classified as type IV, brown skin as type V, and black skin as type VI. In the United States, people from Africa, the Caribbean, Asia, Pacific Islands, Latin America, Native Americans, Latino, Hispanics, Indians, and those of Middle Eastern origin are considered to have ethnic skin.

There is a the paucity of clinical data and studies specifically examining cosmetic concerns in ethnic men, given that this is a growing population with distinct needs regarding gender and skin physiology, it is important for dermatologists to be aware how to treat, counsel, and address the needs of this patient cohort. In fact, a survey conducted in dermatologists in Australia showed that 85% of participants were not confident in managing common cosmetic issues in skin of color, and more than 80% stated they would have liked more teaching in skin of color.

The skin pathophysiology in ethnic individuals has biological differences when compared with fair skin that affect cosmetic treatment needs. Because of the increased melanin, patients with darker skin have inherent protection against extrinsic factors of aging such as damage from UV, and photoaging appears decades later compared with those with lighter skin tones. Photodamage is typically manifested as pigmentary aberrations (lentigines, macules, melasma) rather than rhytides. Moreover, facial aging in patients of color is due to volume loss from deeper muscular layers than dermal layers. Perioral and periorbital lines may not occur as early in patients of color, but there is a tendency toward mid and lower face aging, with manifestations including the formation of nasolabial folds and sagging of the jowl. Skin of patients of color also have thicker more compact dermis and stratum corneum with more cornified layers.

Hair structure is also different in patients of color patients. Black individuals have flat elliptical-shaped hair shafts with curved hair follicles, and fewer elastic fibers anchoring hair follicles to the dermis, whereas the Asian hair shaft is round with the largest cross-sectional area.

Aside from the differences in skin pathophysiology and anatomy in patients of color, there are profound cultural differences that dictate cosmetic concerns, habits, and goals. Ethnic men have historically been hesitant to pursue cosmetic treatments because of fears of being viewed as rejecting their racial identity. As techniques have advanced, and physicians have developed a nuanced and culturally/gender-sensitive approach to beauty, ethnic men can now share cosmetic goals similar to their Caucasian counterpart men. Enhancing physical appearance and combating aging is a shared goal because it is tied to personal success in life.

Antiaging treatments for ethnic men

Restoring a youthful appearance is a common goal of ethnic men, and dermatologists can offer several treatment options either as monotherapy or in a combination approach. Energy-based devices such as those that harness energy from laser/lights and radiofrequency in combination with fillers/neurotoxins and topical cosmeceuticals can reduce the appearance of wrinkles, pore size, and laxity and replete any areas of volume loss.

Lasers

Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing can be considered among first-line therapy for the reduction of fine lines and wrinkling, textural abnormalities, and pore size in ethnic male patients, because it has an excellent safety profile and short downtime. Fractional photothermolysis creates microscopic columns of thermal injury that have a diameter ranging from 100 to 160 μm with a depth of penetration 300 to 700 μm. Because epidermal and follicular structures are spared and melanin is not at risk of targeted destruction, nonablative fractional laser resurfacing can be used successfully in patients with skin of color. Suitable candidates include those with mild/moderate photodamage acne scarring and striae. Caution should be taken in patients with melasma or keloid scars. An ideal treatment regimen has been shown to typically include a series of 4 to 6 treatments with low densities allowing for adequate recovery between sessions. Often pretreatment and posttreatment with hydroquinone-containing creams are useful to prevent hyperpigmentation.

In a retrospective review of 362 patients undergoing nonablative fractional laser treatments with either 1550-nm erbium or 1927-nm thulium fiber laser, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation occurred in only 1.1% of patients, whereas worsening of melasma was noted in 0.9% of cases. Kono and colleagues also demonstrated the safety and efficacy of nonablative fractional 1550 nm laser in patients of color, noting that patient satisfaction was higher when their skin is treated with high fluences than with high densities. Another study using the fractionated nonablative 1440-nm laser in 20 patients (skin types I-VI) showed that 6 treatments were generally required to achieve a significant reduction in pore size.

Radiofrequency

Radiofrequency devices that emit thermal energy to the dermal layers of the skin can stimulate wound-healing mechanisms promoting collagen production and remodeling that ultimately leads to skin rejuvenation. Radiofrequency treatments are safe for all skin types because thermal energy is chromophore independent; thus epidermal melanin is not at risk of destruction. Early generations of radiofrequency devices such as the monopolar Thermage (Solta, Hayward, CA, USA) have been shown to be effective in improving periorbital and jowl laxity in patients of darker skin types. More recently, new generations of technologies, such as that of fractional microneedle radiofrequency, have also been tested for skin rejuvenation in dark skinned patients. Subjects receiving 3 treatments of fractionated microneedle radiofrequency at 4-week intervals experienced clinical improvement in areas such as periorbital wrinkling and high patient satisfaction at the 6-month follow-up.

Microfocused Ultrasound

Microfocused ultrasound technologies (MFU) deliver ultrasound energy to the reticular dermis, and by producing microcoagulation zones, stimulate denaturation, collagen remodeling, and skin rejuvenation without influencing the epidermal layer. Because the energy is not selectively absorbed by chromophores, MFU is safe for darker complexions that have excess laxity. A recent clinical study demonstrated the safety and efficacy of MFU for improving laxity of the skin of the face and neck in 52 adults with Fitzpatrick skin types III to VI. No adverse events were reported, and side effects including erythema self-resolved in the weeks following treatment.

Toxins

Brow furrows, glabellar creases, and crow’s feet resulting from hyperfunctional facial muscles manifests equally in men and women of all races. Moreover, although men seek treatments with neurotoxins to appear more relaxed and youthful, there is also a need for conservative treatments and preservation of some movement to attain a natural appearance and avoid feminization. Prominent and full male eyebrows without a significant arch enhance masculinity. Thus, regardless of race, treatment with neurotoxins should preserve a lower position of the brows and a flatter arch. Botulinum toxin-A is the most common neurotoxin used for the relaxation of glabellar frown lines and off-label for relaxation of the upper and lower hyperkinetic muscles in patients of color. Treatments with toxins should precede at least 2 weeks before treatments with fillers because injections with botulinum toxin can reduce the amount of fillers needed to correct creases and folds. A common goal specific to Asians is the desire to achieve a more open eyelid, and clinically this can be achieved by injecting 1 to 2 units of botulinum toxin-A into the mid lower lid that preserves the shape of the Asian but opens the eye slightly.

Fillers

As mentioned earlier, although people of darker skin have thicker dermis and less perioral/periorbital rhytides, they do experience age-related muscle and volume loss, thus often seek treatments for volume repletion. Because of the reduced rate of collagen degradation in ethnic skin and the collagen-stimulating properties of new generation fillers, fewer treatments are usually necessary to achieve desired volume restoration. The most common fillers used in men include calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC, USA), poly- l -lactic acid (Galderma, Fort Worth, TX, USA), and hyaluronic acid (Juvederm; Allergan, Parsippany-Troy Hills, NJ, USA) ( Fig. 1 ). When injecting fillers in skin of color, one of the most important technical considerations is minimizing the use of multiple puncture techniques. In a clinical trial of 150 patients (skin types IV–VI), multiple puncture technique was associated with a 13% incidence of hyperpigmentation compared with lineal threading technique, whereby the incidence of hyperpigmentation was merely 2%. Adverse effects such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and ecchymosis can be reduced with slower injection rates.