Complications and Revisions

INTRODUCTION

A surgeon should never perform a procedure for which he or she is incapable of dealing with potential adverse consequences. Even in the most capable hands, approximately 1% of flap reconstructions will result in a complication requiring a postoperative intervention.1 For all of the meticulous attention given during a reconstruction, the greatest test of a surgeon’s mettle occurs when a serious complication occurs and must be resolved. Patients often find even a routine and uneventful flap reconstruction to be emotionally challenging. Adding a complication greatly increases anxiety and requires the surgeon to act quickly and effectively and provide appropriate reassurance.

EDEMA

Periocular surgery often causes substantial edema, especially when muscle tissues have been removed and/ or manipulated. Some patients will develop profound edema and will be quite alarmed (Fig. 16.1). In cases where an extensive reconstruction has been performed, this may last for weeks to months. Patients concerned with edema should be seen and evaluated. Luckily, even when swelling is extreme, ocular complication is exceptionally unlikely. Simple measures such as head elevation when sleeping along with reassurance are sufficient in most cases.

Figure 16.1 Edema 1 day following removal of a skin cancer. This will resolve spontaneously but can be frightening to the patient

HEMATOMA

Hematoma formation occurs in less than 1% of facial flap reconstructions. While linear repairs are relatively unaffected by anticoagulation, the incidence of hematoma following adjacent tissue transfer is somewhat higher in patients on anticoagulants.2 With the pervasive utilization of multiple antiplatelet agents, often in combination with warfarin or thrombin inhibitions, patients are at risk of postoperative hemorrhage.3 The management of anticoagulant therapy in patients undergoing cutaneous surgery is an area of evolution. Given the real risk of cerebral and myocardial infarction with anticoagulant change and/or cessation, many surgeons opt to continue anticoagulation therapy during skin surgery, unless a particularly aggressive repair will be required. The authors of this book have not discontinued any form of anticoagulation in 10 years, and multiple of the cases shown in this book were performed in patients on warfarin, clopidogrel, aspirin, and/or a combination of these and similar medications. In the case of warfarin, it is easy to check an international normalized ratio (INR), and if this is markedly elevated, it is reasonable to adjust the dosage.

Minor Hematomas

Small hematomas will often form without a patient being entirely aware that something has gone wrong. Patients who expect swelling may wake up in the morning with a hematoma that has already undergone tamponade and that is not expansile. They may call the physician or may not present until suture removal. Modest, static hematomas, which do not cause tissue compromise, can be managed expectantly and will usually resolve spontaneously and without incident (Fig. 16.2).

Figure 16.2 Minor hematoma on the temple several days postoperatively. This can be allowed to resolve spontaneously

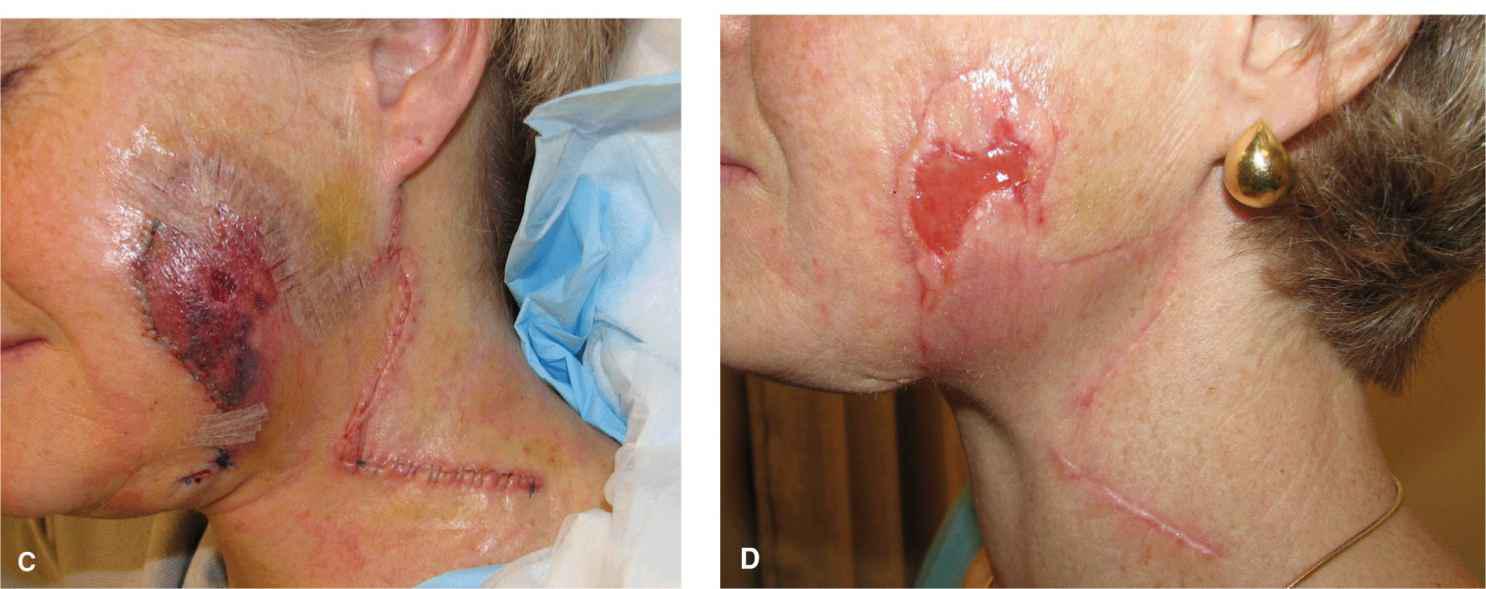

Delayed presentation hematomas will present to the physician at suture removal as a swelling and diffuse ecchymosis (Fig. 16.3). Depending on the extent of the hematoma, either the sutures may be removed and the hematoma can be left to resolve spontaneously or alternatively the hematoma may be drained. A hematoma that has been present for 7 to 10 days will be partly liquid and partly solid. It may be evacuated simply by opening a small portion of the repair and expressing the currant jellylike contents (Fig. 16.4). Hematomas that have been present for longer periods of time will be liquefied and can often be drained with a seroma catheter or similar device (Fig. 16.5).

Figure 16.3 Moderate hematoma of the temple at 1 week. This may be drained for ease of healing, and drainage will be relatively easy. Alternatively, this will likely resolve on its own in several months

Figure 16.4 Drainage of a hematoma that has matured. (A) Hematoma and some residual edema following a linear closure. (B) The wound is opened revealing a currant jellylike hematoma. (C) The hematoma is evacuated and resutured with a small wick

Figure 16.5 A 10-day-old hematoma is drained through a seroma catheter. By this time, the hematoma has liquefied

Acute, Enlarging Hematomas

Acute hematoma formation is a frightening complication for patients and frequently presents with acute, painful swelling and ecchymosis (Fig. 16.6). While this is most common in the hours following completion of the procedure, bleeding episodes may present up to several weeks following surgery. When the surgeon is contacted, the patient is often frightened and uncomfortable. Depending on the size of the bleeding vessel and the location, a hematoma will either tamponade or expand indefinitely. On the forehead or nose, a hematoma may be trapped beneath a fascial layer that restricts the expansion of the bleeding, whereas on the temple or in the perioral area, a hematoma off of the facial or temporal artery may expand to enormous proportions (Fig. 16.7). While unusual, an expanding hematoma can lead to respiratory compromise. In general, expanding hematomas require intervention.4 Left alone, a hematoma also may have a substantial impact on flap viability and outcome and may result in neurovascular damage as well.

Figure 16.6 Typical hematoma presentation the day following surgery. The area is swollen and tender, and the suture line is oozing. This is a patient on aspirin and clopidogrel

Figure 16.7 Large hematoma from a branch of the superficial temporal artery presented immediately after surgery

Drainage of a hematoma can usually be successfully accomplished with local anesthesia (Fig. 16.8), but in complex cases, consideration should be given to deep sedation or anesthesia. The area around a sizeable acute hematoma will be exquisitely tender. Where feasible, anesthesia should be achieved by nerve block combined with local anesthesia infiltrated slowly at a distance from the periphery of the hematoma. The site should be prepped as for surgery in the usual sterile fashion. Once anesthesia has been achieved, the majority, if not all, of the surface sutures should be removed. It is imperative that complete anesthesia be achieved prior to drainage. For many patients, the drainage of a hematoma will be substantially unnerving. Deep sutures should then be severed once at a time to open the reconstruction. If acute hemorrhage is encountered, the entire flap should rapidly be opened and pressure applied. In such cases, a single large vessel is often bleeding freely and is readily clamped and ligated. More often, a firm, fibrous purple clot will be encountered and may be substantially adherent to the flap and the depth of the operative wound. The contents should be evacuated using swabs, gauze, and, as needed, forceps.

Figure 16.8 Acute, expansile hematoma. (A) Operative wound following removal of a basal cell carcinoma. (B) Cheek advancement flap. (C) A hematoma has developed causing pain and swelling. The periphery of the flap is being anesthetized. Achieving anesthesia for a hematoma is a slow, deliberate process working from the edges under the hematoma

The formation of a hematoma leads both to coagulation and to thrombolysis. Particularly in patients on anticoagulants, the wound bed from a hematoma may bleed profusely. Once all clots have been removed, the area should be repeatedly irrigated with saline, and meticulous hemostasis should be reestablished by electrocautery and ligature. The wound edges should then be carefully reapproximated so as to resemble the original surgery. If bleeding from muscle tissue cannot be stemmed, the application of a procoagulant such as Surgicel® may be employed. A sincere effort should be made to stem all bleeding prior to resuturing. In coagulopathic patients on multiple anticoagulants, especially platelet inhibitors, once thrombolysis has been initiated by a postoperative bleed, it may be very challenging to achieve total hemostasis. In rare cases, it may be necessary to reverse anticoagulation and/or utilize fresh frozen plasma to stem active bleeding.

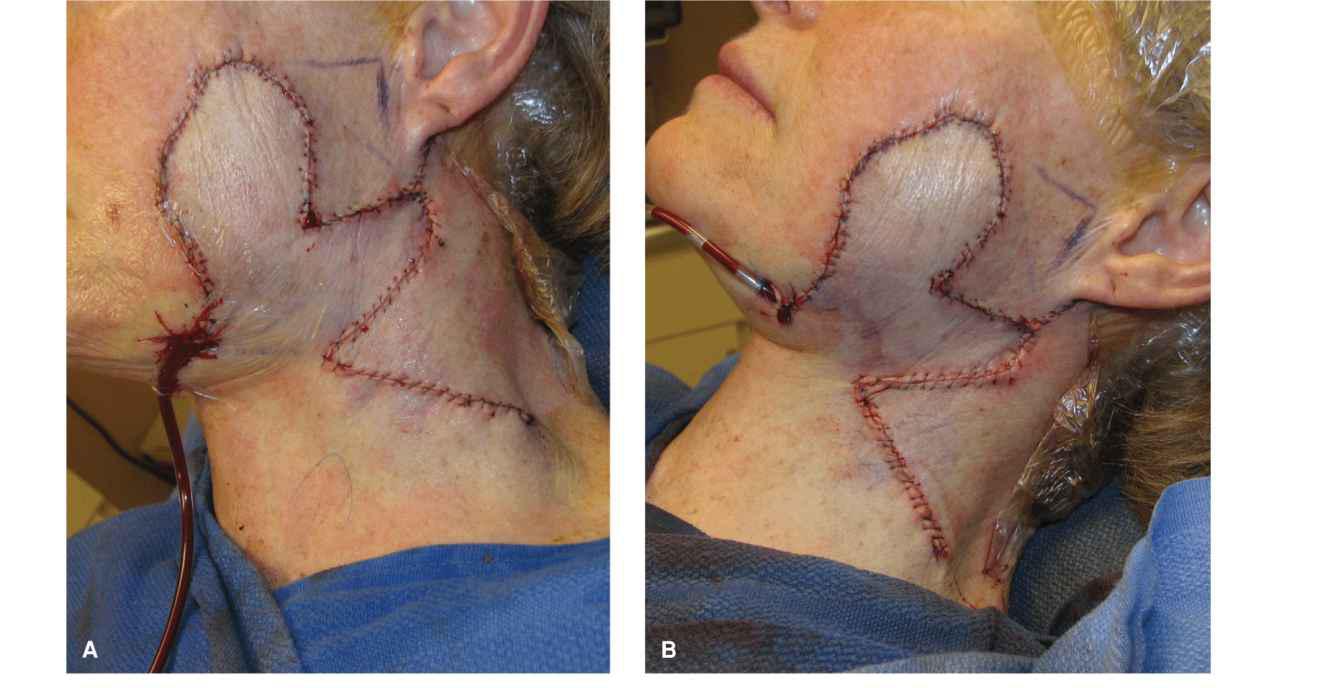

If following removal of a hematoma all bleeding can be stopped and the surgeon is confident of hemostasis, a drain is unnecessary. If a minimal amount of oozing persists, a small wick may be placed. If persistent bleeding is a concern, a formal drain may be utilized (Fig. 16.9).

Figure 16.9 Management of a large hematoma. (A) Large hematoma 1 day following removal of a squamous carcinoma in a coagulopathic patient. (B) The wound is opened and evacuated. (C) A drain is placed. Due to persistent drainage into the drain bulb, the patient received fresh frozen plasma. (D) Suture removal at 1 week. (E) Final healed wound (also after liver transplantation)

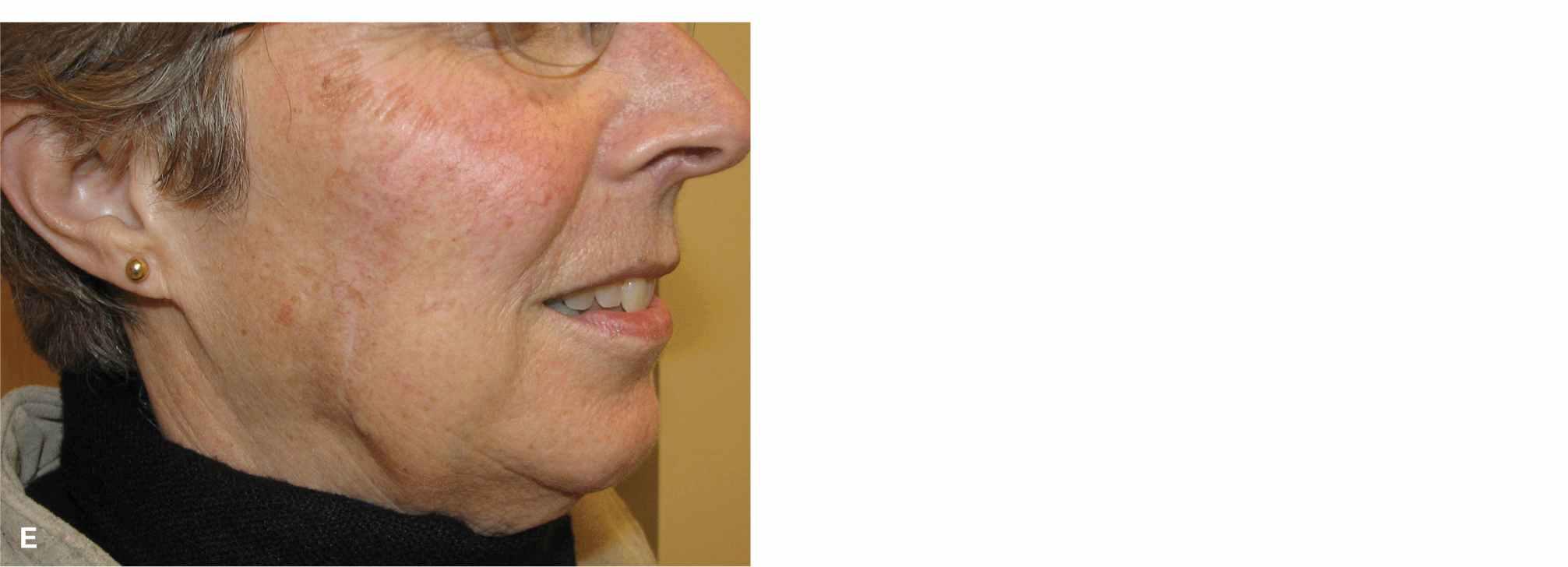

In many cases, following successful management of a hematoma healing will be uneventful, but revision may be needed. The suturing done at the end of a hematoma drainage may not be on pristine, healthy tissue, and the scar line may not be as exact as at the time of original closure. Revision of the scar may be indicated following maturation at 6 months (Fig. 16.10). In some cases, the hematoma itself will have damaged the flap enough to cause ischemia. In such cases, the flap may suffer partial failure (Fig. 16.11).

Figure 16.10 Revision of scar in patient from Figure 6.8. (A) The wound has healed with an inverted scar. (B) The scar is excised, the edges undermined, and the wound aesthetically resutured. (C) Revision at 6 months

Figure 16.11 Consequences of hematoma formation. (A) Large bilobed flap with developing hematoma. Note the amount of blood in the drain tubing. (B) The hematoma has been evacuated and resutured. (C) The primary lobe of the flap has suffered some ischemia from the hematoma. (D) Partial necrosis and healing at 3 weeks postop

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree