Cheek Reconstruction With Skin Grafts

Farooq Shahzad

Babak J. Mehrara

DEFINITION

The cheeks are the largest aesthetic unit of the face.

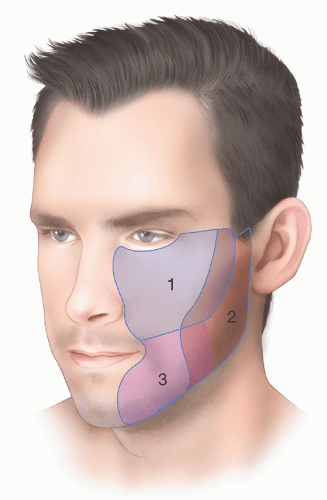

The boundaries of the cheek are medially the nasofacial groove and nasolabial fold, inferiorly the mandibular border, laterally the preauricular crease, and superiorly the infraorbital rim and the line joining the lateral canthus to the helical root.

The cheek is subdivided into three aesthetic subunits: suborbital, preauricular, and buccomandibular (FIG 1).1

These subdivisions are useful for planning reconstruction.

ANATOMY

The face has an abundant blood supply with a rich collateral network. The arterial supply to the cheek is via branches of the external carotid artery. The principal supply is via three sources (FIG 2):

Facial artery and its continuation, the angular artery

Transverse facial artery, which is a branch of the superficial temporal artery

Infraorbital artery, which is a branch of the internal maxillary artery

The veins accompany the arteries.

The lymphatics of the cheek drain to the parotid, submandibular, and submental nodes. Additional drainage occurs to the jugular nodes.

Sensory innervation to the cheek is via three sources:

Maxillary division (V1) of the trigeminal nerve via the infraorbital and zygomaticofacial nerves

Mandibular division (V3) of the trigeminal nerves via the buccal, mental, and auriculotemporal nerves

Cervical plexus (C2, C3) via the greater auricular and transverse cervical nerves

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Cheek defects occur most frequently following skin cancer resection but may also occur after trauma or other causes.

Skin cancers on the cheek can be removed by conventional methods or using Mohs micrographic surgery.

Assessment of margins is important and should be discussed with the patient.

If margin status is in doubt, it is often more prudent to proceed with reconstruction only when the final pathology is reviewed and negative margins are assured.

Many skin cancer excisions or traumatic injuries of the cheek may be repaired primarily. In other cases, local flap reconstruction or skin grafts are more appropriate.

Skin grafts are useful in patients with significant comorbidities in whom facial flaps may be contraindicated, situations in which the blood supply to local flaps has been compromised, large defects that are not amenable to reconstruction with local tissues, or cases in which local flap closure may result in distortion of the adjacent structures such as the eyelid or nose.

For example, skin grafts may be useful in young patients with large superficial cheek skin defects. These patients have tight skin without much redundancy, and thus, attempts to reconstruct larger defects with local flaps will cause distortion of contour or pull on adjacent structures like eyelids.

Skin grafts are also helpful in some cases for men because facial flaps in these patients may change the distribution of hair growth resulting in a noticeable and difficult-totreat problem.

Infrequently, skin grafts may be useful for reconstruction of aggressive or recurrent tumors in which there is a high risk of local recurrence that is more suitable for applying skin grafts to facilitate surveillance.

Finally, skin grafts may be used in combination with flap closures to extend the reach or avoid tension on the base of the flap or to provide coverage for adjoining anatomic regions (eg, eyelid).

The defect is analyzed for the following:

Location, size, and depth of the defect

Involvement of deeper structures (eg, facial nerve, parotid duct, and oral mucosa)

Proximity of the defect to lower eyelid, nasal ala, and lip

Previous radiation and radiation changes. Heavily radiated or compromised wounds may not be amenable to local flaps or skin grafts and may require vascularized tissue transfer depending on the exposed structures and complexity of the wound.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Areas of the face with a concave surface heal well with secondary intention healing.

The cheek is convex, and therefore, secondary healing results in aesthetically unpleasing results.

Exceptions are small preauricular defects and very small medial defects at the alar groove that heal well with local wound care.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Patient selection for skin graft reconstruction is as discussed above.

Full-thickness skin grafts taken from within the face and neck (cranial to the clavicles) will have better color and texture match.

Common donor sites are the preauricular or postauricular areas, neck, upper eyelid, and supraclavicular region.

Scars are ideally placed at the borders of the cheek.

In general, however, subunit principle and excision of normal skin are not necessary or advised. In rare circumstances, the margins of the graft may be adjusted to blend into normal anatomic structures (eg, nasolabial fold or lower eyelid-cheek margin).

Preoperative Planning

The condition of the wound bed is examined. Contaminated wounds or those with eschars will need debridement and dressing changes until an appropriate bed is available for skin grafting.

If possible, skin grafting should be delayed until the wound has granulated enough to decrease contour deformities that may result from deep excisions. In practice, this is not always possible, however, because of contracture and deformity of adjacent structures.

One potential solution is the use of decellularized dermis or other material (eg, Integra) to promote wound filling and granulation, thereby avoiding contour deformities.

Anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents may be discontinued or bridged prior to the procedure; however, the risk of stopping these medications (eg, stroke, MI) should be weighed against skin graft loss and should be individualized.

In most cases, consultation with the patient’s primary care or medical team is needed to make this decision.

The expected postoperative course should be discussed with the patient.

Full-thickness skin grafts initially turn pale and then become hyperemic as they revascularize. They stay pink for several weeks before settling down to their final color. Often, these grafts initially look pin cushioned and fibrotic but soften up over a period of 2 to 3 months. These issues are minimized with optimization of the recipient bed and preservation of the full thickness of the dermis (and even a small amount of subcutaneous layer).

Possible future revision procedures should also be discussed if necessary.

Positioning

Patient is positioned supine, with the head at the edge of the bed.

Small transparent dressings (Tegaderm) are used to tape the eyes closed for protection.

Preoperative antibiotics are administered.

Approach

Skin graft reconstruction of cheek defects can be performed with a full-thickness or split-thickness skin graft.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree