CHAPTER 7 CAPILLARY MALFORMATIONS

KEY POINTS

Pulsed-dye laser can reduce the color of capillary malformations.

Capillary malformations may cause overgrowth of tissues beneath the stain.

Pyogenic granulomas can develop in capillary malformations and are removed.

Symptomatic overgrown tissues are managed by excision.

Resection of a capillary malformation should not leave a worse deformity than the appearance of the lesion.

A capillary malformation (CM) is the most common type of vascular malformation, affecting 0.3% of the population. Recently the causative somatic mutation (GNAQ) has been identified.

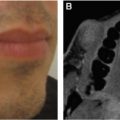

Capillary malformations can cause overgrowth of tissues beneath the cutaneous stain. A child with a CM involving the lower lip and chin is shown (A). Labial hypertrophy during adolescence is seen (B). Continued enlargement in adulthood is shown (C).

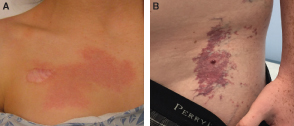

A CM begins as a pink, cutaneous discoloration and then darkens to a purple color over time. A child with a CM of the chest is shown (A). She underwent an unnecessary biopsy to diagnose the lesion at an outside institution that resulted in an unfavorable scar. The diagnosis of a CM is made by history and physical examination; imaging and histopathologic examination are not required. An adolescent male with a darkened CM of the trunk is shown (B). Note the pyogenic granuloma that has developed.

Clinically and histologically, CMs become more similar to venous malformations over time. CMs can be a component of a syndrome and associated with underlying structural anomalies. The primary morbidity of CM is psychosocial distress, because the lesion causes a visible deformity. CMs do not cause pain and are not at increased risk of infection or bleeding. First-line management of CMs is pulsed-dye laser, which effectively lightens the lesion. Laser treatment in infancy or early childhood may yield better efficacy compared with later intervention. Despite pulsed-dye laser, CMs typically redarken over time. Resection of a CM is much less common compared with intervention with pulsed-dye laser.

SURGICAL INDICATIONS

Surgical management of CMs is not mandatory and is reserved for symptomatic lesions (see Video 7-1, Capillary Malformations). Resection and reconstruction should not leave a worse deformity than the appearance of the malformation. The indications for surgical treatment of a CM are pyogenic granulomas, thickening and cobblestoning of the skin, and overgrowth of tissues beneath the lesion. Bleeding pyogenic granulomas require resection. Asymptomatic pyogenic granulomas are also removed, because they have a high risk of hemorrhage. Thickening of the integument and hypertrophy of the subcutis, muscle, and bone beneath the CM typically do not begin until late childhood. The primary indication to debulk overgrown tissues is lowered self-esteem. Patients will request surgical intervention to improve their appearance. Rarely, osseous overgrowth can cause malocclusion or a leg-length discrepancy. CMs do not have an increased risk of blood loss during resection unless varicosities have developed. Because CMs are typically diffuse, complete extirpation is rarely possible. Instead the goal of the procedure is usually to perform a subtotal resection to improve the patient’s symptoms.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

TIMING OF INTERVENTION

A pyogenic granuloma requires intervention regardless of the age of the child. If possible, treatment should be delayed until at least 6 months of age, because before this time the patient’s risk of anesthesia is greater than for an adult. Overgrowth usually does not occur until adolescence, and thus surgical procedures are rarely performed at younger ages. Patients typically present requesting improvement in their appearance or intervention to facilitate fitting into clothes. Epiphysiodesis of the distal femoral growth plate may be required around 11 years of age to correct a leg-length discrepancy. Overgrowth of the maxilla/mandible can cause an occlusal cant and/or malocclusion that may necessitate an orthognathic procedure after the completion of skeletal growth (16 years of age in girls and 18 years of age in boys).

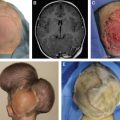

A rare surgical indication in early childhood is to remove a problematic lesion on the scalp. Because the scalp has significant laxity during infancy, resection of a CM may be considered before 6 months of age to facilitate the procedure. Although uncommon, if a young child already has significant overgrowth of tissues of the face that will require surgery to improve a deformity, consideration should be given to early resection. Because long-term memory and self-esteem begin to form at approximately 4 years of age, debulking overgrown facial tissues before this time will treat the deformity before it causes psychosocial distress; the patient will also not remember the procedure.

PYOGENIC GRANULOMA

Because pyogenic granulomas involve the reticular dermis, interventions that do not treat the entire depth of the skin have an approximately 50% recurrence rate (for example, shave, cryotherapy, and superficial cautery). Definitive management is full-thickness excision of the lesion. If a pyogenic granuloma develops in a localized CM, the surgeon should consider removing the entire CM to obviate the risk of future pyogenic granulomas in the remaining CM. Small pyogenic granulomas can be managed with needlepoint cautery to coagulate the base of the lesion through the dermis.

LIP OVERGROWTH

One half to two thirds of patients with a CM of the face will have soft tissue hypertrophy; the lip is the most commonly overgrown structure. Preoperative imaging is unnecessary. Vertical lip resections should not be performed for CM, because the lesion is benign and the excision is subtotal (margins are not required). Vertical scars on the cutaneous lip are avoided. The contour of the lip can be improved by partial resection with a transverse mucosal incision. The procedure may be performed in adults with a local anesthetic. The area of the overgrown lip is outlined, and the junction of the keratinized and nonkeratinized lip is tattooed. Next, an elliptical excision is centered on either side of the keratinized/nonkeratinized junction. I inject the area with 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine. As minimal a volume as possible is used to limit distortion of the lip and to reduce the amount of postoperative swelling that can cause increased fibrosis and an enlarged lip. A small Beaver blade is used to resect the vermilion, mucosa, submucosa, and a small amount of muscle. Tooth show is used as a guide to determine how much tissue should be resected. I overcorrect slightly to account for postoperative swelling and subsequent fibrosis, which contribute to lip fullness. After undermining the vermilion and mucosa, the wound is closed with 5-0 Vicryl suture, followed by interrupted 6-0 chromic suture. Patients are maintained on a full-liquid diet for 2 weeks to prevent suture line dehiscence.

Occasionally an individual will have preferential overgrowth of either the vermilion or mucosal area of the lip. The transverse elliptical resection can be adjusted to remove more of the vermilion or mucosa as needed. Patients with severe hypertrophy may require a second-stage resection to achieve the best outcome. Individuals who have overgrowth of the cutaneous aspect of the upper or lower lip can have improvement with a mucocutaneous incision along the white roll. A skin flap is raised along the cutaneous lip, underlying subcutaneous tissue is removed, and excess skin is trimmed.

CHEEK OVERGROWTH

Resection of a cheek CM is much less common than lip procedures. Surgical intervention for a diffuse facial CM should focus on improving the patient’s appearance with localized, staged excisions without causing a significant deformity. Diseased tissue should not be removed if there is a risk of iatrogenic morbidity. It is critical to avoid facial nerve injury. Facial nerve dissections or parotidectomy should not be performed. The primary tissue that is overgrown with a CM is the subcutis. When the lesion extensively involves the face, strategies to improve the area include:

Excision of excess skin and subcutaneous tissue

Removal of the buccal fat pad

Contour burring of the zygoma

If the overgrowth is located on the lateral cheek, a preauricular incision is used. Medial fullness is resected through a mesolabial incision. Patients often lack a mesolabial crease, and placing a scar in this location improves their appearance. Alternatively, a circular excision can be used to access the overgrown tissue, and the purse-string closure can be revised at a second stage. An end-stage CM with significant discoloration, skin thickening, and fibrovascular overgrowth may benefit from excision and reconstruction with a skin graft.

I generally do not use intraoral approaches to remove subcutaneous lesions. I prefer to make a cutaneous incision and remove abnormal subcutaneous tissues sharply under direct vision. I believe in the principle of trading scar for contour. Patients are most satisfied with achieving the best symmetry, which is noticed beyond conversational distance at the expense of a scar that can only be appreciated on close examination (similar to having a longer scar instead of a shorter scar and dog-ears at each end). Intraoral excision is more difficult and less predictable than direct cutaneous extirpation; there is also an increased risk of infection and facial nerve injury.

I do not perform preoperative imaging when resecting a facial CM. Blood loss is reduced by infiltrating the surgical site with epinephrine. If the volume of local anesthetic with epinephrine is limited by the amount of anesthetic that can be given based on the weight of the patient, I will infiltrate an epinephrine-only solution to ensure maximum vasoconstriction of the surgical site (1 ml of 1:1000 epinephrine in 200 ml normal saline = 1:200,000 solution).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree