CHAPTER 35 Calf Augmentation

Summary

Despite vigorous workout regimens, some men are unable to achieve a more muscular appearance, particularly to the calf region. This chapter addresses the anatomy of the calf and the golden ratio of calf aesthetics. Then, it discusses forms of implant and the two forms of addressing calf insecurities: medial calf augmentation and lateral calf augmentation.

Introduction

Over the course of time, a bulky and muscular physique has been a sign of virility and strength. From idealized statues from classical antiquity to modern- day action figures, the male muscular form has been central to the image of the “manly” man. Despite vigorous workout regimens, some men are unable to achieve a more muscular appearance, particularly to the calf region; these men then present to surgeons for aesthetic calf augmentation. Over the past 50 years, various surgeons have tackled the procedure and described novel incision sites and varying implant shapes and sizes; however, despite all these publications, the procedure overall has changed very little. While there has also been interest in using fat to produce improvement in the calves, placement of silicone prostheses is the gold standard for calf augmentation and provides excellent cosmetic results when performed in the appropriate patient in a stepwise, methodical manner.

Brief History

Initially introduced by Carlsen in 1972, 1 , 2 calf augmentation was described using an implant carved from silastic foam to help an equestrian who desired a larger calf to fill out her riding boot. In 1979, Glitzenstein 3 used silicone gel calf implants for patients with atrophy of the leg and muscular aplasia. In 1984, Szalay 4 introduced torpedo-shaped implants that were placed beneath the fascia. In his technique, however, he did recommend the use of relaxing incisions in the fascia. In 1991, Aiache 5 introduced lenticular-shaped implants. In 2006, Gutstein 6 described a new silicone prosthesis that enhances the curved medial lower leg, which he termed a “combined calf–tibial implant.”

Over time, various authors have discussed options for implant positioning. The early pioneers of the procedure, Carlsen and Glitzenstein, introduced the implant into a subfascial plane. However, in 2003, Kalixto and Vergara 7 described a calf augmentation with placement of the implant in a submuscular pocket, between the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. The dissection that they proposed was done far away from the union of the gastrocnemius muscles where there were no vessels or nerves that could be damaged. It was noted, however, that these patients had a more tedious dissection and prolonged recovery than the patients who had undergone subfascial implant placement as described in previous reports. Use of muscle relaxants was paramount in these patients. The rationale for submuscular placement, according to the authors, was that they were able to gain better camouflaging of the implant.

In 2004, Nunes and Garcia 8 described a method for calf augmentation that placed the implant in a supraperiosteal plane associated with fasciotomies. Ultimately, it is at the surgeon’s discretion where to place the implant; however, based on anatomical studies and countless clinical studies by various authors, it seems that calf augmentation via the subfascial plane is a safe procedure that allows for reproducible results with minimal risk of postoperative complications and significantly less pain from the patient’s perspective obviating the need for more invasive techniques.

Anatomy

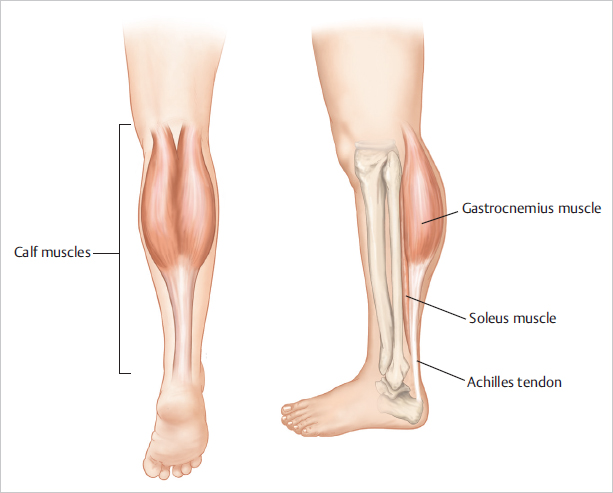

The shape of the calf is defined primarily by the volume of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. In addition, the crural bones and the subcutaneous fat work in tandem with the muscles to further define the calf.

The calf is made up of two muscle groups: the gastrocnemius and the soleus ( Fig. 35.1 ). The gastrocnemius has two heads and lies superficial to the deeper soleus muscle. The two heads of the gastrocnemius are connected to the condyles of the femur by strong tendons. The medial and larger head originates from a depression at the upper and back part of the medial condyle and from the adjacent part of the femur. The lateral head arises from an impression on the side of the lateral condyle and from the posterior surface of the femur immediately above the lateral part of the condyle. The fibers of the two heads unite at an angle in the midline of the muscle in a tendinous raphe, which expands into a broad aponeurosis. The aponeurosis, gradually contracting, unites with the tendon of the soleus and forms the calcaneal tendon (the Achilles tendon).

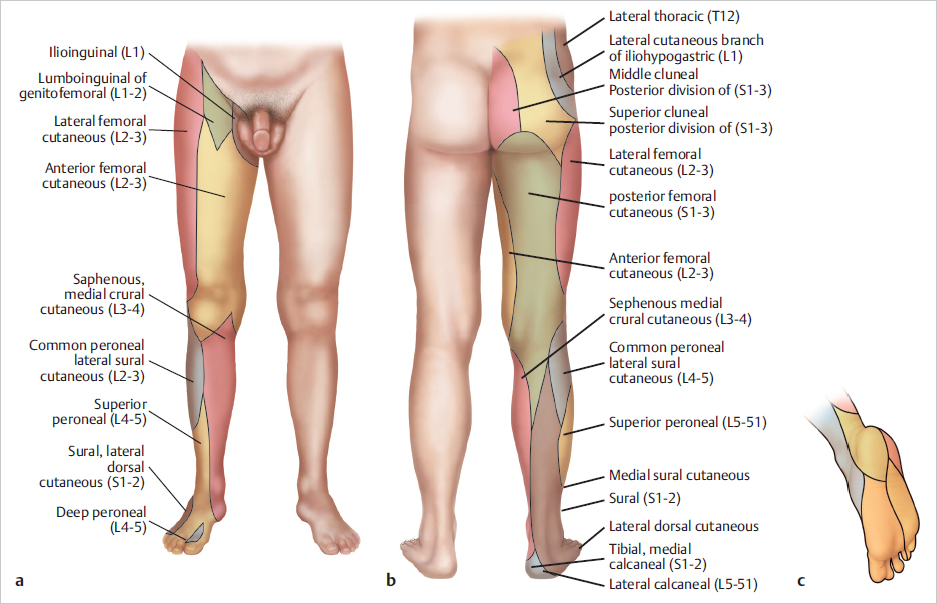

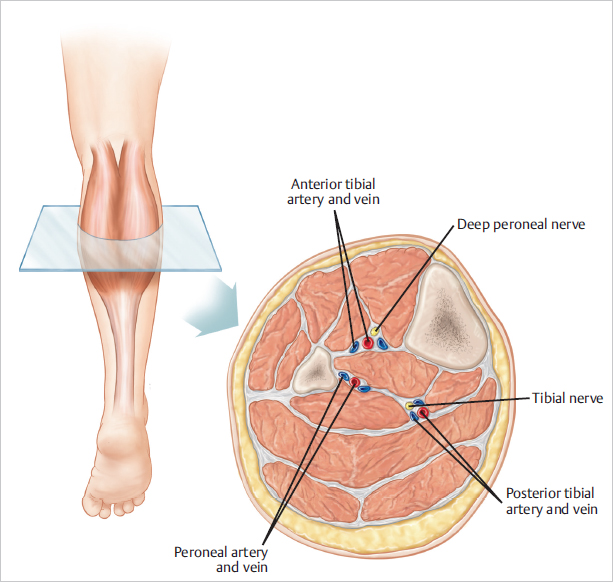

In performing the dissection to attain a subfascial plane, the lateral and medial cutaneous nerves, branches of the peroneal nerve and tibial nerve, respectively, are potentially encountered. These nerves provide sensory innervation to the skin ( Fig. 35.2 ). The medial sural cutaneous nerve originates from the tibial nerve of the sciatic and descends between the two heads of the gastrocnemius. It can be identified prior to diving between the heads of the gastrocnemius in the upper midline calf region. The lateral sural cutaneous nerve supplies the skin on the posterior and lateral surfaces of the leg and travels in a subcutaneous plane alongside the small (short) saphenous vein, joining with the medial sural cutaneous nerve to form the sural nerve. Major arterial, venous, and nerve structures are deep within the calf and remain undisturbed during a routine calf augmentation procedure ( Fig. 35.3 ).

The subfascial plane in the medial calf region is relatively avascular, allowing for creation of a relatively bloodless plane. That being said, care must be taken to avoid injury to the short saphenous vein that lies deep to the investing fascia of the leg and superficial to the gastrocnemius in the midline posteriorly. This vein drains into the popliteal vein in the popliteal fossa.

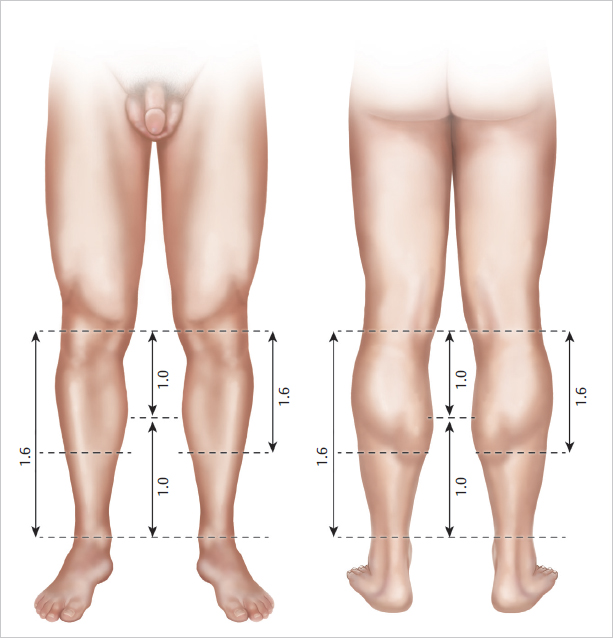

When considering the calf anatomy, one must also consider proportions of the body and aesthetics of the calf region. Over the years, physicians and mathematicians have tried to define beauty and what constitutes a beautiful male form. In 1991, Howard9 first described the ideal length proportions of the calves, basing his paper’s conclusions on drawings done by Leonardo da Vinci. Howard defined the golden ratio of calf aesthetics to exist when the distance between the ankle and the lower border of the gastrocnemius muscle was equal to the distance between the knee and the most prominent point on the medial curvature of the gastrocnemius muscle; the entire length of the gastrocnemius should be 10.6 times the former value. 9 This golden ratio correlated to the golden section of 1:1.618 as defined by the Italian mathematician Bonacci or what German astronomer and physicist Johannes Kepler called the “divine proportion” 9 ( Fig. 35.4 ). Using these “standards” of calf aesthetics, one can better understand the defect that needs to be corrected and improved with a properly chosen implant.

Patient Selection

Calf augmentation was originally designed to fill defects left following oncologic surgery, after trauma or infection, or because of genetic abnormalities. There are many causes for unilateral or bilateral calf deformities and they include, but are not limited to, the following:

Congenital hypoplasia because of agenesis of a calf muscle or adipose tissue reduction.

As a sequelae of clubfoot (talipes equinovarus), cerebral palsy, polio, and spina bifida.

Because of poliomyelitis or osteomyelitis.

Following fractures of the femur and as a result of burn contractures.

While calf implants do not improve function of the affected extremity, patients are able to achieve greater symmetry between an unaffected and affected limb and are able to achieve significant volume addition through the use of silicone prostheses.

Since its initial introduction, calf augmentation surgery has become a widely popular aesthetic procedure to help patients gain more shapely legs. Whether it is a bodybuilder who is looking to “bulk up” the leg despite a vigorous exercise regimen or the average patient who wants a more shapely calf region, there are implants of various shapes and sizes to help add volume to a hypoplastic calf.

Patient Consultation

The consultation begins with a thorough medical history of the patient. Special attention is taken to ask specifically about trauma to the extremity, history of surgery to the foot or ankle, history of vascular insufficiency that may put blood flow at risk, history of venous insufficiency or leg swelling that may prolong postoperative edema in the lower extremity, and any history of nerve damage or sensory deficits as may be seen in patients with diabetes mellitus.

At the time of consultation, the patient is asked what bothers him specifically about his calf. Preoperative goals are assessed at this point. A patient who has unrealistic expectations and is unable to comply with the strict postoperative instructions is deemed a poor candidate for augmentation. Patients who have congenital anomalies, a significant size disparity between the two calves, or bilateral hypoplasia are informed that several surgeries may be required to attain symmetry and achieve the augmentation they desire. In the typical consultation, patients are asked if their deficiency lies primarily in the medial aspect of the calf, the lateral aspect of the calf, or whether they would like a larger calf size overall. The reason for this distinction is to help the surgeon plan the right implant style for surgery.

After completion of the history, the patient’s calves are evaluated. First, symmetry of the two sides is assessed, and any disparity is brought to the attention of the patient. Although the majority of patients present with a preexisting asymmetry of the calves, not many patients note the difference, and this can be a source of medicolegal matter in the future.

If the patient suffers from clubfoot deformity or a previous bout of polio, leg asymmetry is noted. The physician then evaluates the quality of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle. A person who has very thin tissues or significant hypoplasia of the calf may not be able to adequately accommodate a large implant.

Patient Evaluation

Next, the patient’s calves are measured in circumference at the midportion. A second measurement, from the popliteal fossa (proposed incision line) to the insertion of the Achilles tendon, is also taken. Having this second measurement allows one to assess the maximum length of implant that can be accommodated in the calf.

When determining the type of implant to use, we largely base the determination on the desires of the patient. However, as mentioned previously, we also take into account the length from popliteal fossa to insertion of the Achilles tendon to better define the length that will be accommodated. If the patient merely wishes to have more definition in the calf, then we will use the style 2 Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies implants in most cases. With the style 2 calf implant, there is a greater enhancement of the medial calf muscle ( Fig. 35.5 ).

If, however, the patient wishes to have more overall volume to the calf region and is looking for more of a block-like appearance to the calf, or what we term the “football player calf,” then we favor the style 1 implants ( Fig. 35.5 ). With the style 1 implant, there is a greater enhancement of the entire calf region, which in our practice is best suited for patients who already have a great deal of muscle volume (e.g., bodybuilders) and just want an overall increase in volume.

Style 3 implants are used for lateral head augmentation and are rarely used. Each of the different style implants has a range of sizes to fit each patient’s need (Table 35.1). Regardless of the implant chosen, the position of the implant is still in the subfascial plane and minimizes dissection around key neurovascular structures. With experience, the surgeon will be better able to determine the best implant for each patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree