CHAPTER 12 CRANIOFACIAL BONES

KEY POINTS

Vascular anomalies involving the craniofacial bones are relatively uncommon.

Lesions do not always require treatment; intervention is based on the type of vascular anomaly and symptoms.

Bone overgrowth is managed differently than bone loss.

Treatments available for osseous vascular anomalies include sclerotherapy, embolization, vincristine, sirolimus, interferon, bisphosphonates, resection, and bone grafting.

Patients with an osseous vascular anomaly are best managed in a vascular anomalies center by physicians who are focused on these lesions.

Vascular anomalies involve bone much less commonly than soft tissues. In the craniofacial region capillary, venous, and lymphatic malformations most frequently affect osseous structures. Other vascular anomalies that can involve bone include arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and rare vascular tumors (for example, epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas and kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas). Major vascular anomalies that do not affect bone are infantile hemangiomas, congenital hemangiomas, and pyogenic granulomas.

SURGICAL INDICATIONS

Vascular anomalies of the cranium and facial bones are rarely malignant, and thus treatment is usually not mandatory. The primary morbidity is psychosocial, because lesions can cause a visible deformity. Other problems include occlusal cant, malocclusion, exophthalmos, enophthalmos, and cranial defects. Before considering intervention, the diagnosis must be confirmed. MRI and/or CT are performed to identify the lesion, determine the extent of disease, and develop a management plan. Vascular anomalies can cause either osseous hypertrophy or loss. Physical examination and imaging will determine whether the patient has increased or decreased bone. Treatment of overgrowth is reduction by contour burring or osteotomies. Management of hypoplasia includes intralesional injection of sclerosants, embolization, systemic pharmacotherapy, bone replacement, and/or osseous augmentation.

If an individual has an obvious deformity, improvement of the area can be performed before 4 years of age when long-term memory and self-esteem begin to form. Early skeletal intervention, however, may be associated with a higher rate of recurrent deformity compared with delayed treatment. Another period to consider intervention for psychosocial morbidity is when the patient is older and requests surgery. Correction of a malocclusion or an occlusal cant is typically not initiated until completion of facial growth (16 years old in females and 18 years old in males). If a vascular anomaly of the face or cranium is causing significant symptoms (for example, bleeding, infection, pain, and threatening vital structures), intervention is necessary independent of the age of the patient (see Video 12-1, Craniofacial Bones).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

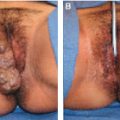

CAPILLARY MALFORMATION

A capillary malformation is the most common type of vascular malformation and frequently affects the head and neck. Soft tissue and bone underneath the cutaneous stain can hypertrophy over time; the mechanism is unclear. Facial lesions can cause overgrowth of the maxilla and/or mandible that may result in asymmetry, occlusal cant, or malocclusion. A LeFort I osteotomy can improve vertical maxillary overgrowth; other orthognathic procedures may be necessary to correct occlusion or mandibular enlargement. In some cases orthodontic intervention can improve the occlusion to maximize masticatory function until children have completed facial growth and are candidates for orthognathic procedures. Overgrowth of the facial bones causing a deformity can be corrected by burring the cortex to reduce the projection of the area at any age. Although capillary malformation of the scalp may cause hypertrophy of the underlying cranium, treatment is rarely necessary, because the area is camouflaged by hair.

VENOUS MALFORMATION

A venous malformation causes bone destruction and ultimately hypoplasia. The most common location of an intraosseous venous malformation is the craniofacial region. Bony involvement can occur in combination with adjacent soft tissue disease, or the bone can be affected primarily. In the literature intraosseous venous malformations have been erroneously called hemangiomas. (infantile hemangiomas do not involve bone). Venous malformations of the craniofacial region typically cause osteolysis, with a spongy, sunburst-like expansion of the bone.

An osseous venous malformation does not require intervention unless the lesion is symptomatic. Management includes sclerotherapy, resection, or orthognathic surgery. Generally sclerotherapy is our preferred treatment, because it is less morbid than resection. Many lesions will respond favorably and not require further intervention. If sclerotherapy is not possible or fails, the area is excised. Cranial lesions undergo full-thickness calvarial resection with minimal margins; the defect is usually filled with autologous bone graft (especially in the pediatric population). Reconstruction of the cranium with alloplastic materials (for example, porous polyethylene) is generally reserved for adults who have completed cranial growth. Venous malformations of the facial bones (for example, the zygoma, maxilla, and mandible) are most commonly reconstructed with bone grafts from the cranium. If the venous malformation is primarily intraosseous without adjacent soft tissue involvement, recurrence is uncommon after resection. In contrast, if a significant soft tissue component is present, further procedures to treat the underlying bone grafts may be necessary. Orthognathic intervention can be required if a venous malformation causes a malocclusion.

LYMPHATIC MALFORMATION

A lymphatic malformation can cause either bone overgrowth or loss. The most common osseous site of a lymphatic malformation is the craniofacial region. Isolated macrocystic or microcystic lymphatic malformations involving soft tissues and bone can cause hypertrophy. Osteolysis and marginal sclerosis are illustrated on radiographic examination; solitary spaces less than 2 cm may be present. Lesions of the scalp may result in a prominence of the cranium that may not be camouflaged by hair. The area can be flattened by burring the ectocortical surface. A lymphatic malformation of the maxilla or mandible can lead to facial asymmetry, occlusal cant, and/or malocclusion. Ostectomy or orthognathic procedures may be necessary.

Gorham-Stout disease and generalized lymphatic anomaly are anomalies that primarily affect bone. Gorham-Stout (“disappearing bone disease”) causes osteolysis of contiguous sites. The bone resorbs, resulting in pain, fractures, and significant morbidity. Imaging shows progressive osteolysis and cortical loss. The ribs are most commonly involved, followed by the cranium, clavicle, and cervical spine. Almost all lesions have an adjacent soft tissue lymphatic malformation. Patients are treated with weekly subcutaneous interferon and monthly intravenous bisphosphonates. Recently oral sirolimus has shown efficacy. These drugs may prevent continued bone loss but rarely cause remineralization. Severe morbidity can require surgical intervention with bone grafts that have a high resorption rate, because they are placed into a diseased recipient site.

Generalized lymphatic anomaly (“lymphangiomatosis”) is a multisystem disorder affecting noncontiguous sites. Osseous lesions have discrete lytic areas and radiolucencies confined to the medullary cavity. The number and size may increase, but progressive osteolysis and cortical loss do not occur. Approximately one half of individuals have a soft tissue lymphatic anomaly at the site of bone involvement. Patients can also have lesions of the spleen or liver and pleural effusions. Symptomatic individuals are treated similarly to patients with Gorham-Stout disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree