CHAPTER 10 ARTERIOVENOUS MALFORMATIONS

KEY POINTS

Surgical treatment of arteriovenous malformations must be individualized based on several variables.

Arteriovenous malformations are not malignant and do not require radical resection for cure.

Surgeries for arteriovenous malformations should not cause a worse deformity than the appearance of the lesion.

Diffuse arteriovenous malformations are best managed by focused, subtotal procedures to improve symptoms and the appearance of the patient.

Before surgical intervention, embolization is performed to reduce blood loss for regional and diffuse arteriovenous malformations.

An arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a problematic lesion. Arteries are connected to veins through abnormal vessels called the nidus. Because a capillary bed is not present, blood is shunted from the arterial to venous circulation, resulting in venous hypertension and arterialized veins. Reduced oxygen is delivered to tissues, causing them to be ischemic and prone to ulceration. Although AVMs are present at birth, they may not be noted until childhood or adolescence. Lesions slowly worsen over time, particularly during puberty.

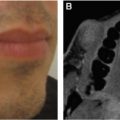

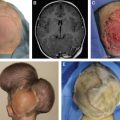

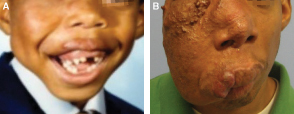

The progression of an AVM is shown. This 6-year-old patient had a stage 1 lesion (A). At 29 years of age he has a stage 3 lesion (B).

AVMs can be localized, regional, or diffuse. They progress through four stages:

Stage 1: Warm, skin discoloration, and fast flow on Doppler examination

Stage 2: Growth, palpable pulsations, and enlarged veins

Stage 3: Ulceration, bleeding, and pain

Stage 4: Congestive heart failure

The primary morbidity of AVMs is that their appearance causes psychosocial problems. Other complications occur as they progress: pain, bleeding, and ulceration. Treatments include embolization and/or resection; pharmacotherapy does not exist. Embolization involves cannulation of an artery remote from the AVM (usually the femoral artery) and insertion of an embolic agent into the nidus or draining veins. Generally, embolization is first-line treatment of AVMs; surgical intervention is reserved for small lesions or symptomatic patients after embolization. Most AVMs are diffuse and involve multiple anatomic structures, so complete extirpation is rarely possible; the goal of intervention is usually to alleviate symptoms and control the AVM.

Despite subtotal and presumed “complete” extirpation, most AVMs reenlarge. Recurrence typically occurs during the first year after intervention, and 86% will reexpand within 5 years. Patients who do not have a recurrence 5 years after intervention are likely to have long-term control. However, 5% will experience regrowth more than 10 years after surgery. Patients and families are told that an AVM is likely to recur after resection, and further treatment may be needed in the future.

SURGICAL INDICATIONS

Intervention for an AVM is not mandatory; lesions can be observed AVMs have a high recurrence rate after resection Subtotal resection or embolization can stimulate an AVM to enlarge Resection should not cause a worse deformity than the lesion Lower-stage lesions are the least likely to recur Surgical intervention is individualized based on stage, size, location, age, and symptoms |

Intervention for an AVM is not mandatory. Subtotal resection of a nonproblematic lesion may cause ischemia and stimulate the AVM to enlarge and cause morbidity. Resection and reconstruction should not leave a worse deformity than the AVM. Variables that determine whether an AVM should be resected include: (1) stage, (2) age, (3) location, and (4) size.

STAGE 1

Stage 1 AVMs typically are not problematic unless they cause a deformity and affect the patient’s self-esteem. Localized lesions should be removed before they progress to a higher-stage AVM. Resection of a stage 1 AVM gives the lowest recurrence rate and best chance for long-term control or cure. Localized lesions are most likely to be removed completely with the least morbidity. Waiting until the lesion expands complicates the resection and reconstruction and increases the likelihood of an unfavorable long-term outcome. If a localized lesion involves an anatomically unfavorable area (for example, the tip of the nose or upper eyelid) that would require complicated reconstruction, leaving a worse deformity than the lesion, I recommend waiting until the AVM worsens and becomes symptomatic in the future. Approximately 16% of stage 1 lesions do not progress long term.

Resection of a regional or diffuse stage 1 AVM should be based on its size and location. Because the entire lesion can rarely be removed, surgical intervention for large asymptomatic lesions is less common. However, if it is possible to completely resect the AVM in an anatomically favorable area (for example, the trunk), prophylactic excision and reconstruction should be considered before the lesion progresses. In contrast, if a large AVM is located on the face and extirpation and reconstruction would leave a significant deformity, it is generally best to wait until the lesion becomes problematic before intervention.

STAGE 2

Stage 2 AVMs are managed similar to stage 1 lesions. However, there is a lower threshold to intervene because the AVM is growing. Stage 2 lesions are more likely to be symptomatic, because they are enlarging. Pulsations from the lesion can also be bothersome to the patient.

STAGES 3 AND 4

Stage 3 or 4 AVMs require treatment for deformity, bleeding, pain, ulceration, and/or congestive heart failure.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

TIMING OF INTERVENTION

Stage 3 and 4 AVMs require immediate treatment, regardless of the age of the patient. Milestones for resection of stage 1 and 2 AVMs are: (1) 6 months, (2) 3 years, and (3) late childhood/early adolescence. Generally an AVM should not be removed before 6 months of age. At this time the patient’s risk from anesthesia is greater than for an adult. In addition, a young infant is less able to tolerate a surgical procedure. If a large lesion is located on the scalp, removing it before 6 months of age should be considered to take advantage of scalp laxity that exists during infancy.

AVM | Definition | Surgical Treatment |

Localized | 1-2 tissue planes Complete resection can be closed with local tissue | Subtotal excision if problematic location Complete excision if nonproblematic location |

Regional | =2 tissue planes Complete resection requires distant tissue | Subtotal excision if problematic location Complete excision if nonproblematic location |

Diffuse | =3 tissue planes Complete excision is not advisable | Subtotal excision |

if it is likely that a patient will require surgery, a common time I will intervene is between 3 and 4 years of age. Because long-term memory and self-esteem begin to form at approximately 4 years of age, removing an AVM at this time will improve a deformity before the child’s self-esteem begins to form, and the patient will likely not remember the procedure. Another period to intervene is during late childhood/early adolescence when the child is able to communicate whether he/she would like the procedure. if a patient has a minor deformity or a large lesion requiring significant reconstruction, it is often best to wait until the child verbalizes that he or she wants surgery. If the lesion is minor, it may be able to be removed under local anesthesia by waiting until the child is older. If the lesion is significant, then waiting until the child can be a willing participant facilitates the process for the family and surgeon. The surgical strategy for AVMs is based on the extent of the lesion.

LOCALIZED AVMS

A localized AVM involves one to two tissue planes (for example, the skin and subcutaneous tissue), is well defined, and theoretically is able to be entirely removed with linear closure. Unfortunately, these are the least common types of AVMs. Generally, I remove localized AVMs without preoperative embolization, because bleeding is not significant after the area is infiltrated with a local anesthetic containing epinephrine. Avoiding embolization reduces overall treatment morbidity for the patient. If the volume of local anesthetic with epinephrine is limited by the amount of anesthetic that can be given based on the weight of the child, I will infiltrate an epinephrine-only solution to ensure maximum vasoconstriction of the surgical site (1 cc of 1:1000 epinephrine in 200 cc of normal saline = 1:200,000 solution).

Lesions located in anatomically sensitive areas (for example, the face) should have minimal or no margins taken. An AVM is not a malignancy, and evidence does not show that a significant resection margin lowers the recurrence rate. An AVM often involves a larger area than is appreciated clinically and radiographically. Findings of biopsies taken outside of the lesion have shown abnormalities. In my experience if microscopic disease is left after a localized AVM is removed, the recurrence rate is very low. Cautery during the procedure and fibrosis may destroy residual AVM tissue. If a lesion is located in a nonsensitive area (for example, the abdomen), larger margins can be taken as long as they do not complicate the extirpation and reconstruction (see Video 10-1, Arteriovenous Malformation).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree