Chapter 57 Care of a burned hand and reconstruction of the deformities

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Introduction

The human hand is not only an organ to handle tools but also the apparatus to express emotion. Although it accounts for only 2.5–3% of the total body surface area, a hand can become involved in up to 80% of the treated burn injuries.1,2 A hand may be burned as an isolated injury, or in conjunction with other body areas. It is rarely spared from injuries if burns involved >60% TBSA. Hand burns occur more frequently at the workplace3,4 and are more likely to be flame burns or electrical burns. Scalds, explosions or open flames are the likely causes of injuries occurred at home and contact burns to the hand and scald injuries are common in small children.5

Functional recovery of an injured hand, in short, depends upon early stable wound coverage, an adaptable skeletal framework, movements and strength of musculotendinous structures restored while the magnitude of original injuries governs functional impediment6; loss of the thumb, for instance, accounts for a 50% function loss of the whole hand.7

Management of a burned hand

Initial assessment

The basic principle of patient evaluation and treatment for trauma patients is followed. That is, the injuries involving the hand are quite often a part of extensive thermal injury.2,3 Access to the information concerning the circumstances under which the accident took place is essential in patient management; the knowledge concerning causative agent and the causative factors of the accident, e.g. flame, grease, chemical, water or electrical and duration of contact, is essential in planning the course of initial treatment for the victims and the wounds. While assessing the overall condition of a burn victim to ascertain a resuscitation plan, i.e. gathering the information about tetanus immunization, hand dominance, occupation, and past and present medical illness, any first-aid measures such as cooling and irrigation of the burned sites are required; wounds inflicted by heat retained longer with some agents such as hot grease, and caustic effects of alkaline fluid, for instance, require a different approach and care during the period soon after the accident.

Examination of the hand must include assessing the magnitude of injuries. While the extent of burn depth – superficial/partial-thickness and full-thickness – is usually easy to distinguish, assessing a deep but superficial burn wound can be difficult. Generally speaking, distinguishing wounds between superficial/first degree and superficial partial-thickness/second degree burns is much more difficult. They are usually erythematous, painful and blistered. The wounds blanch readily with pressure. Wounds with deeper burns may appear pallid or may be erythematous but often mottled. The magnitude of sensory changes, however, varies. Full-thickness/third degree burns are pale and assume a brownish color. The wound is anesthetic and leathery in consistency. Coagulated blood vessels may be readily visible.2,8 Although a burn wound is classified as fourth degree when the underlying soft tissue and/or bone are involved, the depth classification rarely falls into such clear categories (Fig. 57.1).

The thickness of skin and the underlying soft tissue can vary depending upon the parts of the hand and the age of patients; these factors often affect the magnitude of injuries. That is, the skin over the back of the hand, for instance, is thin, particularly in children and in the aged. Consequently, the area is more vulnerable to deeper injuries; the area is prone to edematous swelling and more aggressive measures of decompression are needed during the acute phase of injury.2,3,5

Initial care of a burned hand

Escharotomies are carried out either at bed side using an electrical cautery or a cold knife once the vascular status of the involved limb is judged to be compromised. Incisions are made over the medial and the lateral mid-axial lines through the skin down to the muscle layers. The line of release extends both caudad and cephalad beyond the margin of tissue swelling to assure complete release. The incisions on fingers are made along the mid-lateral line just dorsal to the digital neurovascular bundle that may include the Cleland’s. A single incision is made in the radial side of the thumb and the ulnar side for the fingers.2 Releasing incisions may be extended into the web spaces to assure the integrity of vascular supplies to the intrinsic musculatures of the hand. Incisional releases may be carried out to involve the forearm muscle compartment and the carpal as well as the Guyon canals in electrical burns (Fig. 57.2).

The wounds following decompressive maneuvers are covered with cadaveric skin graft or non-adhesive dressing impregnated with antimicrobial ointment.2,6 Continuous elevation of the injured limb is important to curtail edematous changes. The wounds are managed during the following 10–14 days by performing additional wound debridement if indicated, and wound closure by means of skin grafting and/or skin flap techniques.

Definitive surgical care of burned hand wound

Any wounds judged to be unequivocally third-degree burns, or those showing no progressive signs of healing, require surgical intervention. The procedure may be delayed for victims with extensive injuries; surgical care of other vital sites takes place ahead of the hand wound coverage, even though such a delay in caring for hand wounds often results in deformities caused by thickening of the scar and contraction of the joints. Diligent exercise and physiotherapy could minimize the undesirable consequences.2,3

The use of a sheet of skin graft, partial in thickness, is preferred to cover an open wound of the dorsum of the hand because of a better achievable outcome, i.e. pliable scars and good color match. However, the use of a meshed skin graft in 1 : 1 or 1.5 : 1 in ratio, a minimally meshed graft, has been reported to provide a similarly good outcome.2,3,5,6 In addition, artificial dermal regeneration template materials such as Integra®, Pelnac® and Terudermis®, may be used for initial wound coverage. The resultant wound, with fully vascularized dermal template in place, is covered with a partial-thickness skin graft.9 Similarly, Aldoderm®, an inert cadaveric dermis, may be used.6

The depth of burn wound that involves the palm, in most instances, is superficial, as it is protected by the thick epidermal layer of the palmar skin. The recovery is consequently much quicker and less eventful in comparison with an open wound of the dorsum of the hand. A conservative regimen of treatment when and if used to manage an open wound involving the dorsum of the hand results in a much longer time to heal than an injury that involves the palmar surface. The use of full-thickness skin grafting appears to provide excellent results but may be limited to wounds of a small area.10 On the other hand, the efficacy of FTSG as reported by others, could not be ascertained.11,12

Finger joints, especially over the dorsum, tend to become exposed because of thinness of the skin and high vulnerability to injury. In order to minimize boutonnière deformities, the DIP and PIP joints are maintained at full extension with the Kirschner wires placed intramedullarily for a period of time.2 The use of skin flaps will be necessary in instances where the joint, the tendinous as well as neurovascular structures become completely devoid of soft tissues, coverage. The results with the use of skin flap, especially mobilized from a distant site, on the other hand, are not entirely satisfactory because of the thickness of skin over the joint structures.2,6

After care

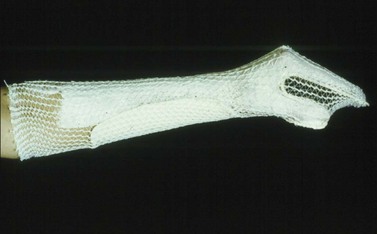

The care of a burned hand soon after the treatment consists of hand elevation to minimize tissue swelling and pain.2 Persistent edematous swelling of the hand is believed to result in a loss of joint mobility and dorsal skin laxity impairing joint movements, especially at the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints level. A protective splint that will maintain MCP joint flexed at 70° and the PIP, as well as DIP joints kept at full extension, with the hand in a position of ‘safety’, is used (Fig. 57.3). Otherwise, a contracted palm, stiff and contracted PIP and extended DIP joints, the classic boutonnière’s deformity, is a common sequela noted in a hand improperly positioned.1 A temporary pre-manufactured splint can be placed on the patient with the initial dressing application and continued after the initial assessment. A customized hand splint should be used to support hand position over 2–3 days post-injury since a pre-manufactured splint may cause unwanted pressure points in the hand. Removal of the splints for range of motion exercise at least twice a day is recommended.13,15 The hand is kept in a protective posture and elevated for 4–5 days following surgical treatment.

Although a partial-thickness skin graft is the most common material used for wound coverage and wound resurfacing, contraction of a graft site is common. Splinting of the hand and fingers in a protective configuration is preferred; the patients would assume the usual posture once the post-surgical exercise regimen is completed.14 Pressure garments are used often for patients soon after the wound closure to control excess swelling and scar formation.13 Wrapping the injured fingers with Coban is also used to control tissue edema.

Management of established burned hand deformities

General principles

Although the primary objective of reconstructing burned hand deformities is to restore hand function, recurrent problems of joint contractures and stiffness can ensue, despite early wound coverage, continuous use of hand splinting and physiotherapy. This is particularly true if the hand injury was not the only site of burns, when reconstructive measures are delayed or deferred for individuals with extensive burns or when reconstruction of structural deformities such as eyelids, mouth and neck takes precedence over hand deformities. The procedures may be modified because of the paucity of donor tissues that could be used for reconstruction.16

Two years of waiting following recovery from the injury has been the precept and the practice in hand reconstruction followed for the past 50 years. An early reconstructive endeavor has been advocated in recent years, especially for those who have shown full recovery from the injury and whose deformities are limited to the hand.2 It is important for both the surgeon and the patient to have a clear understanding of therapeutic objectives, technical details and consequences one may encounter while recovering from the procedures. It is important to inform the patient of the truth about the procedures and for the surgeon to learn if his/her patient has a realistic expectation about the outcome of reconstruction.

Reconstructive methods

The following are the methods used most commonly for correcting hand deformities: