5

Burns and Frostbite

Evaluation and management of the acutely burned patient is a common requirement of the plastic surgeon on-call. Rapid assessment, stabilization, and triage are essential for decreasing morbidity and mortality associated with burn injury. Commonly, the initial interview will be subsequent to the evaluation performed by the emergency room personnel. It is imperative, however, to remember to initiate measures to stop the burning process and practice universal safety precautions to confer increased safety for both the patient and the caregiver. If a child is burned and the mechanism of injury does not fit the burn pattern or if the patient was burned under unlikely circumstances or conditions, consider abuse.

Burns

Burns

Initial Assessment – The ABCs

Airway

• Establish a patent airway via manual (chin lift, jaw thrust) or surgical techniques (cricoidectomy, tracheostomy)

• Assess for inhalational injury: signs and symptoms include soot deposits in the oropharynx, carbonaceous sputum, singed nasal hair, facial edema, hoarseness; determine whether the burns occurred while the patient was in an enclosed space

Table 5–1 The Glasgow Coma Scale (Score = E + M + V)

Eye opening (f) |

|

Spontaneous | 4 |

To speech | 3 |

To pain | 2 |

No response | 1 |

Best motor response (M) |

|

Obeys verbal command | 6 |

Localizes painful stimulus | 5 |

Flexion: withdrawal | 4 |

Flexion: abnormal | 3 |

Extension | 2 |

No response | 1 |

Best verbal response (V) |

|

Converses and oriented | 5 |

Converses but disoriented | 4 |

Inappropriate words | 3 |

Incomprehensible sounds | 2 |

No response | 1 |

• Measure carboxyhemoglobin level: >10% requires oxygen therapy and is highly suggestive of an inhalation injury that requires intubation

• General criterion for intubation:

Glasgow Coma Score <8 (Table 5–1)

Glasgow Coma Score <8 (Table 5–1)

Inhalation injury

Inhalation injury

Deep facial and neck burns

Deep facial and neck burns

Facial burns with associated TBSA burns >40%

Facial burns with associated TBSA burns >40%

Large TBSA burns – to allow adequate resuscitation

Large TBSA burns – to allow adequate resuscitation

Oxygenation or ventilation compromise

Oxygenation or ventilation compromise

PaO2 <60

PaO2 <60

PCO2 >50

PCO2 >50

RR>40

RR>40

Breathing

• Provide humidified oxygen by facemask

• Expose chest to assess ventilatory exchange, chest excursion, degree of chest wall injury, and presence of circumferential burns to the thorax

• Consider thoracic escharotomy for deep injury to the chest with associated ventilatory compromise

Circulation

• Establish vascular access with large-bore, high-flow venous cannulation. Avoid injured area if possible.

• Initiate monitoring: BP, pulse, temperature

• Consider invasive arterial lines for monitoring and frequent laboratory blood draws

Disability

• Gross assessment of neurological status (mnemonic tool = AVPU) Alert

Responds only to Vocal painful stimuli

Responds only to Painful stimuli

Unresponsive to all stimuli

• Glasgow Coma Scale (Table 5–1)

Exposure

• Remove all clothing and debris to assess for gross injuries and for burn severity

• Prevent hypothermia by increasing the room temperature, covering the patient with clean warm linens, and infusing warm IV fluids

Burn Severity Assessment

For initial acute resuscitation, the following information is necessary:

• Height, weight, and age of the patient

• Depth of the burn injury; whether the burns are second or third degree

• Percentage of the total body surface area burned

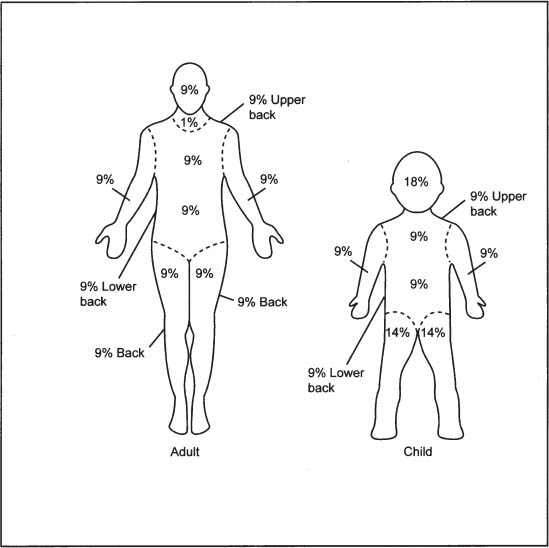

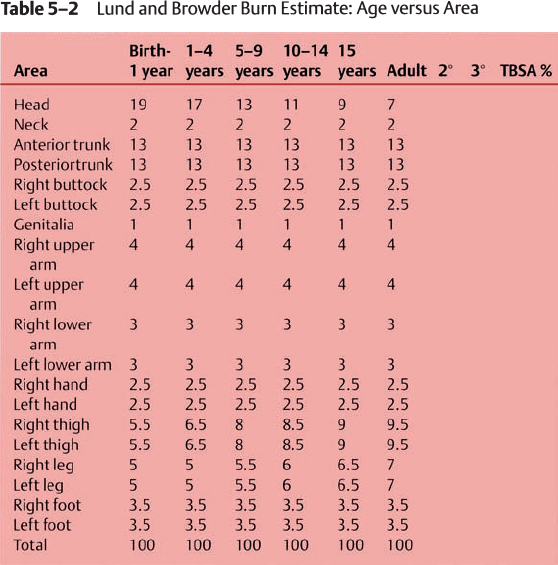

Figure 5–1 The “rule of nines” for adults and children.

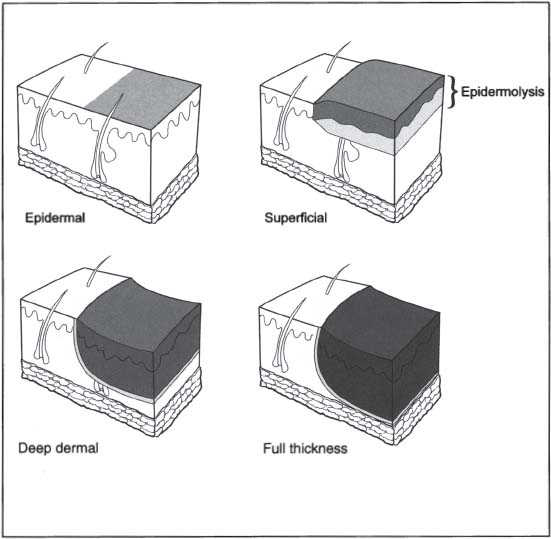

The percentage of total body surface area (TBSA) can be estimated by the “rule of nines” (Fig. 5–1), or more accurately with burn charts (Table 5–2). Generally, the patient’s hand (palm and fingers) is estimated as 1% of their total body surface area. The Burn Wound Classification is illustrated in Fig. 5–2.

Epidermal Burns, First Degree (Fig. 5–3)

• Zones of injury are confined to the epidermis.

• Similar to sunburn

• Nonblanching erythema

• Very painful

• Heals in one week

• No significant scarring

Figure 5–2 Burn wound classification.

Partial-Thickness Burns, Superficial Second Degree (Fig. 5–4)

• Confined to the upper third of the dermis

• The edema layer between the injured layer and normal dermis causes blistering.

• Commonly, these are the result of brief hot-liquid exposure.

• Wounds are wet, pink, and blistering.

• Wounds heal in 10 to 14 days with minimal scarring.

Partial-Thickness Burns, Mid-dermal Second Degree (Fig. 5–5)

• Result from longer hot-liquid exposure, grease, and flash flames

• Wounds are red, with minimal exudates and moderately painful.

• Wounds heal in 2 to 4 weeks with moderate scarring.

Figure 5–3 First-degree epidermal burn.

Figure 5–4 Superficial second-degree burn with blistering and epidermolysis.

Figure 5–5 Mid-dermal second-degree burn.

Figure 5–6 Deep-dermal third-degree burn with areas of full-thickness involvement.

Partial-Thickness Burns, Deep Dermal Third Degree (Fig. 5–6)

• Result from exposure to flames, grease, chemicals, and electricity

• Wounds are usually dry, white, and minimally painful (due to damage to nerve endings)

• Generally, wounds heal in 3 to 8 weeks with severe hypertrophic scarring.

• Excision and grafting will accelerate closure.

Full-Thickness Burns, Third Degree (Fig. 5–7)

• Result from high energy, and prolonged thermal exposure (chemicals, flames, electricity, explosions)

• Wounds are dry, white, or exhibit immediate eschar formation.

• Wounds are painless and insensate.

• These wounds need debridement and grafting to promote healing.

Burn Patient Resuscitation

Patients who require intravenous crystalloid resuscitation and possibly fluid balance monitoring with a Foley catheter placement are

Figure 5–7 Full-thickness burn.

• adults with second and third degree burns >20% TBSA

• children (<14 years of age) with burns >15% TBSA

• infants (<2 years of age) with burns >10% TBSA

All other patients can be managed with oral hydration.

Urine output is used to gauge the success of fluid resuscitation. If there is any question as to the patient’s ability to pass urine, place a Foley catheter. Lactated Ringer’s solution should be started as soon as possible after the time of the burn. The volume of fluid given in the first 24 hours for adult victims is determined by the Parkland Formula:

4 × weight (kg) × % BSA = volume of fluid for 24 hours

These estimates are based on second- and third-degree burn injuries only.

Pediatric patients have increased fluid requirements secondary to differences in BSA to weight ratio and require larger volumes of urine for excretion of waste products. The volume required in the first 24 hours for the burned pediatric patient is estimated using the Galveston Formula (established at the Shriners Institute for Burned Children, Galveston, TX):

[2000 cc times TBSA] + [5000 cc times burn surface area (m2)]

where TBSA (m2) = 0.007184 × (height in cm)0.725

× (weight in kg)0.425

BSA (m2) = TBSA × % surface area burned (i.e., rule of nines)

The rate of infusion for Parkland and Galveston formula:

• Half of the determined volume is given within the first 8 hours of the time of the burn.

• The remaining volume is given during the succeeding 16 hours.

Fluid requirements beyond the first 24 hours are determined based on the patient’s weight and evaporative losses, and adjusted according to the patient’s response (i.e., urine output). Maintenance volume of fluid is calculated in L/day as

• 100 mL/kg for first 10 kg

• 50 mL/kg for second 10 kg

• 20 mL/kg for each additional kg of body weight

In addition:

Evaporated losses related to the burn wounds/per day

= 3750 mL × BSA* (m2)

* (BSA burn surface area)

This volume is then added to the maintenance volume and divided over 24 hours.

Alternatively, the maintenance volume per day in the postacute resuscitation period is calculated:

[1500 mL × TBSA* (m2)] + [3750 mL × BSA (m2)]

*(TBSA total body surface area)

Ultimately, this calculation should be adjusted to ensure adequate end-organ perfusion as monitored by the patient’s urine output, which should be >0.5 cc/kg/h for adults or 1 cc/kg/h for children.

Burn Patient Triage

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree