Postdischarge complications (%)

Mx

IBR

DBR

Readmission for treatment or surgery

10

16

15

Wound infection requiring antibiotics

19

25

28

Unplanned removal of implant

–

10

7

Surgery to remove some or all of flap

–

4

6

Patients considering bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy and bilateral breast reconstruction are often referred through family history clinics after having discussed options, including screening and the use of currently available pharmaceutical agents to reduce breast cancer development.

Patients wishing to be considered for delayed partial breast reconstruction may attend because of asymmetry following breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy. These patients attend to discuss possible reconstructive options because of the impact that breast asymmetry has on their everyday quality of life.

6.4 Assessing the Patient’s Fitness for Reconstructive Surgery

There are a variety of factors which need to be considered when considering a patient’s suitability for breast reconstruction, including age, co-morbidities, body mass index, smoking history, diabetes, steroid/other drug therapy and religious affiliation [6, 7].

6.4.1 Smoking

There are more than 4,000 chemicals in cigarette smoke, including nicotine and carbon monoxide [8]. One effect of nicotine is to cause vasoconstriction of the dermal–subcutaneous vascular plexus. This has important consequences as in reconstructive surgery many tissue flaps rely on this plexus for survival [9]. As well as inducing a hypoxic state and causing vasoconstriction, smoking can lead to increased platelet aggregation, which results in the formation of tiny thromboses in capillaries. This is detrimental to wound healing, which relies heavily on blood flow in newly formed capillaries. Smokers have higher levels of fibrinogen and haemoglobin, which increase blood viscosity and increase the likelihood of blood clotting, and blood flow can be reduced by up to 42 % in smokers [10]. The combination of decreased oxygen delivery to tissues, the thrombogenic effects of smoking and increased viscosity and reduced flow could be the reasons why wound healing in smokers is significantly impaired.

The link between smoking and wound healing was first documented in the 1970 s. Problems with wound healing in smokers have been documented at multiple sites in the body. One study of patients undergoing abdominoplasty found that smokers were 3.2 times more likely to have wound problems than non-smokers. The number of cigarettes smoked in this study was not, however, a reliable predictor of those likely to develop wound healing complications [11]. Facelifts in smokers have been reported to be associated with a 12.5 times increased risk of developing retroauricular skin necrosis compared with non-smokers [12]. A study of 425 patients undergoing mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery and after adjusting for other confounding factors identified smoking as an independent predictor for wound infection and skin necrosis regardless of the number of cigarettes smoked [13]. The odds ratio for infection was 2.95 for light smoking (1–14 g/day) and 3.46 for heavy smoking (more than 15 g/day). The odds ratio for necrosis and epidermolysis was 6.85 for light smoking and 9.22 for heavy smoking.

In patients undergoing pedicled transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap breast reconstructions, the number of wound infections was higher in both current and former smokers [14]. Complications related to the reconstruction were significantly more likely in current smokers (odds ratio 3.9) and former smokers (odds ratio 3.5) than in non-smokers. A study by Padubidri et al. [15] looking at patients having TRAM flaps and tissue expanders reported the complication rate using tissue expanders for smokers was 37.1 %, which was statistically higher then the 26.6 % for non-smokers. In the TRAM flap group, active smokers had a significantly higher overall complication rate and a significant increase, in particular, of mastectomy flap necrosis. A study of 716 patients having free TRAM flaps showed significantly higher numbers of abdominal flap necrosis, mastectomy flap necrosis and abdominal hernias in smokers [16]. Mastectomy skin flap necrosis occurred in 18.9 % of smokers and 9 % of non-smokers (p = 0.005). This study demonstrated a dose effect, with smokers who had a history of smoking more than a pack of cigarettes (20 cigs in a pack) a day for 10 years being at increased risk of developing problems compared with smokers who had smoked for a smaller number of pack-years (55.8 % vs 23.8 %). One observation in this study was that delayed breast reconstruction in smokers was associated with a significantly lower rate of wound complications compared with immediate breast reconstruction in smokers. The risk of wound complications in delayed reconstructions was in fact similar to the rate in non-smokers. Complications were also less common in women who stopped smoking 4 weeks or more before surgery. A study by Gill et al. [17] examined risk factors and associated complications in 758 patients having deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flaps for breast reconstruction and found the risk factors associated with breast or abdominal complications included smoking (p = 0.001), postreconstruction radiotherapy (p = 0.001), and hypertension (p = 0.0370). Smoking and postreconstruction radiotherapy were the only significant risk factors for fat necrosis in this study.

6.4.2 Interaction with Obesity and Diabetes

It is recognised that cigarette smoking, obesity, age, diabetes and nutrition are all factors which play an important role in wound healing. Smokers who are obese or who have diabetes are at an even greater increased risk of wound healing problems than smokers without these risk factors. McCarthy et al. [18] studied 1,170 patients undergoing expander/implant reconstructions. They maintained a prospective database which included the variables of age, smoking status, body index, history of diabetes, hypertension and/or radiation as well as the timing of the reconstruction (immediate or delayed) and the laterality of reconstruction. The chances of developing complications were 2.2 times greater in smokers and 2.5 times greater in women over the age of 65 years. Patients who were obese had nearly twice the odds of having a complication. The same was true for patients with hypertension. The odds of reconstruction failure were five times greater in smokers, and failure was nearly seven times greater in obese patients and four times more likely in those who had hypertension. This study concluded that smoking, obesity, hypertension and age over 65 years were all independent risk factors for perioperative complications following expander implant breast reconstruction.

6.4.3 Smoking Cessation

There is one small randomised clinical trial involving 108 patients on the effect of preoperative smoking intervention on postoperative complications; there were 40 patients in the control group and 68 patients in interventional group [19]. Patients assigned to intervention were given counselling and nicotine-replacement therapy. The study showed a significant reduction in complications in the interventional group, with a reduction in wound-related complications and the need for secondary surgery. In this study patients stopped smoking 6–8 weeks before surgery and did not smoke for 10 days after the operation. In the literature there is no consensus on the optimal duration of preoperative smoking cessation, but there is some evidence that there are potential benefits from even a brief period of abstention. Most studies are, however, retrospective studies and have inherent weaknesses in their design.

6.4.4 Diabetes Mellitus

Studying any risk factor in isolation is always difficult because patients with diabetes often have other associated risk factors, such as obesity. One study of skin-sparing mastectomy flap complications after breast reconstruction showed a significantly increased risk of skin-sparing mastectomy flap complications in diabetics [20].

6.5 Postmastectomy Radiotherapy and Its Impact on Breast Reconstruction

Indications for postmastectomy radiotherapy have expanded over the past decade. One study of 919 patients who had breast reconstruction separated them into three groups: mastectomy with postoperative radiotherapy before reconstruction (n = 57), immediate reconstruction then postmastectomy radiotherapy (n = 59) and reconstruction without postmastectomy radiotherapy (n = 665) [21]. Overall, the complication rates for patients having radiotherapy either before or after mastectomy were significantly higher than those for controls, 40 % versus 23 % (p < .001). Immediate reconstruction before postmastectomy radiotherapy increased both the overall rate of complications (47.5 % vs 23.2 %) and the rate of late complications (33.9 % vs 15.6 %) compared with controls (both p < .001). Delayed breast reconstruction in patients who had either had or not had postoperative radiotherapy produced similar complication and satisfaction rates, but prior radiotherapy was associated with decreased aesthetic satisfaction compared with no postmastectomy chest wall radiotherapy, with only 50 % of patients being happy in the group who had radiotherapy compared with 66.8 % in those who did not have radiotherapy.

A particular issue when using implant-based reconstructions in patients likely to have breast radiotherapy is how best to manage these patients. The literature suggests that there is a significantly increased risk of capsular contracture and other secondary complications in patients who receive radiotherapy compared with patients with who have breast reconstruction with implants who do not have radiotherapy [22, 23]. Complications after irradiation of implants are also commoner than one sees in patients undergoing autologous breast reconstruction who received radiation [24]. Some prefer to delay breast reconstruction in patients in whom it is clear that postoperative radiotherapy is required, whereas others are happy to use implant or autologous reconstructions. This lack of consensus can make it difficult for patients who are likely to need postmastectomy radiotherapy when they are considering their options for reconstruction. They may receive conflicting advice from different individuals because individual surgeons differ in their approach to breast reconstruction in the presence of postoperative radiotherapy.

6.6 Evaluation of Candidates for Breast Reconstruction

Important factors in assessing whether patients are suitable for breast reconstruction and determining the optimal technique include assessment of a patient’s general health, the body habitus, breast size and shape, extent of any mastectomy scar, site of any mastectomy scar, the thinness of the mastectomy flaps, previous radiotherapy, the smoking history and patient preference.

It is important to assess the quality of the tissue that is present and is likely to remain when performing a breast reconstruction. There is a need to determine the amount of skin and soft tissue required to create acceptable symmetry before being able to determine what might be appropriate options (Table 6.2).

Table 6.2

Options for breast reconstructionbreast reconstruction

Technique | Indications for | |

|---|---|---|

Immediate reconstruction | Delayed reconstruction | |

Prosthesis | Small breasts | As for immediate reconstruction plus well-healed scar plus no radiotherapya,b |

Adequate skin flaps | ||

Tissue expansion and prosthesis | Adequate skin flaps | As for immediate reconstruction plus well-healed scar plus no radiotherapya,b |

Tension-free skin closure | ||

Small to medium-sized breasts | ||

Myocutaneous flaps | Larger skin incision | As for immediate reconstruction |

Doubtful skin closure | ||

Large breasts | Can be used if there has been previous radiotherapy | |

6.7 Whole Breast Reconstruction: Patients with Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer in Whom Mastectomy Is Recommended

6.7.1 Treating the Breast Cancer

For patients undergoing mastectomy as their primary surgical option, it is important not to delay removal of the cancer and removal of or biopsy of regional lymph nodes as this may impact on the patient’s long-term prognosis. A recent audit showed a huge variation in the time patients waited for mastectomy alone compared with mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction [3]. If it looks as though it is going to take a long time either for the patient to choose her reconstructive option or to assemble a team to perform a reconstructive procedure, then other options for the patient should be considered. One of these options, which is underutilised in many centres, is to give systemic therapy as the initial treatment. For premenopausal women and those postmenopausal women with large oestrogen-receptor-negative or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive cancers, then neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an excellent option, particularly if the oncologist has already considered that it is likely the patient will receive chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting [5]. In HER2-positive cancers, dramatic rates of complete disease response, including disappearance of ductal carinoma in situ, is possible with the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy together with trastuzumab [25]. In postmenopausal women with large tumours, almost 80 % are oestrogen-receptor-positive and these cancers respond well to aromatase inhibitors [26, 27]. In such women, use of an aromatase inhibitor for a number of months to shrink the cancer will allow over half of these women to become suitable for breast conservation or they can take aromatase inhibitors for a few weeks as a temporary measure while consideration is given to the best form of reconstruction.

Should the scheduling of reconstructive surgery be delayed for any reason, then an option is to excise the invasive cancer through an appropriately placed incision that does not interfere with later breast reconstruction procedures. This can allow adjuvant systemic therapy to be administered prior to mastectomy and reconstruction.

A useful option in some patients is to perform an initial sentinel lymph node biopsy in a patient with an invasive cancer who has no obvious nodal disease on clinical and ultrasound assessment of the axilla. One of the values of preoperative axillary assessment using a combination of imaging with fine needle aspiration cytology and/or core biopsy or sentinel lymph node biopsy is that it allows assessment of the likelihood and extent of any axillary lymph node involvement. This helps evaluate the likely need for postmastectomy radiotherapy. Although there are some who believe that postoperative radiotherapy has limited impact on the cosmetic outcome of whole breast reconstruction, most surgeons believe radiotherapy has a significant negative impact on breast reconstructions, particularly if breast implants are being used [21–24], allowing them to delay reconstruction until the completion of treatment [28]. Knowledge of the likely requirement for postoperative radiotherapy can influence the decision to proceed with immediate breast reconstruction and, if so, then the preferred technique. Although there are some who believe that it is not possible, with any degree of certainty, to determine whether postoperative radiotherapy is likely to be needed, it is clear that it is possible, with a high degree of accuracy by preoperative assessment of the type and extent of the primary cancer in the breast and any nodal involvement, to predict those who are likely to need postoperative radiotherapy [28]. One major reason patients receive postoperative chest wall radiotherapy after mastectomy is multiple axillary node involvement, and thus an initial sentinel lymph node biopsy to assess the status of the axilla prior to mastectomy and consideration of reconstruction is a sensible approach. At the same time as sentinel lymph node biopsy is performed, it is also possible to remove the central subareolar ducts, and this can assist in a decision about whether the patient is suitable for nipple sparing during the mastectomy [29].

6.8 Choosing Options

6.8.1 Implants and Expanders

Breast implants and expanders are best suited for breast reconstruction in women with smaller breasts with thick mastectomy flaps and minor degrees of ptosis [30]. For women who wish to avoid major surgery involving donor sites and scars on other parts of their body, breast reconstruction using implants may be the option of choice. This technique is also worthy of consideration in patients considering bilateral mastectomy leading to a good level of post operative symmetry. When this is performed as a delayed procedure, a period of tissue expansion is required prior to the placement of the definitive implant. In the immediate setting, however, a skin-sparing approach during mastectomy improves the quality of the final result [31]. Total submuscular implant placement can sometimes lead to upward displacement of the inframammary fold. To address this problem, the site of origin of the pectoralis major muscle should be released or detached and the inferior pole of the implant should be covered with an acellular dermal matrix to achieve enhanced projection in this important area [32]. Good candidates for this technique have small to moderate-sized breasts, good quality skin and show an absence of established glandular ptosis. Young patients requesting bilateral risk-reducing surgery are good candidates for implant-based reconstructions using this technique. In older age groups, the technique may still lead to very satisfactory results when combined with symmetrising surgery on the contralateral side. Irradiated tissues rarely do well with implant-based breast reconstructions [32]. During the reconstructive consultation, the limitations of this technique for unilateral reconstruction must be communicated and the patient advised that symmetry is possibly usually only when clothed with the contralateral side supported in a bra.

6.8.2 Use of Tissue Matrices

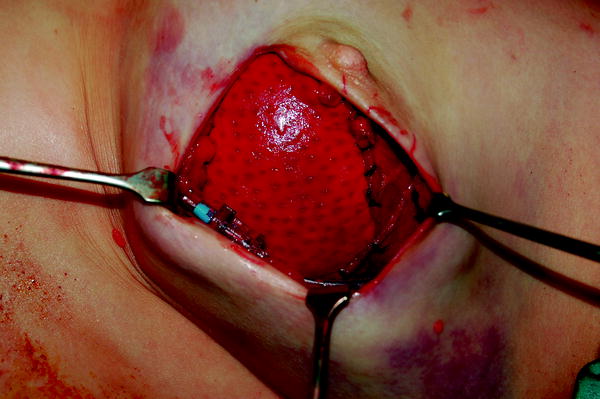

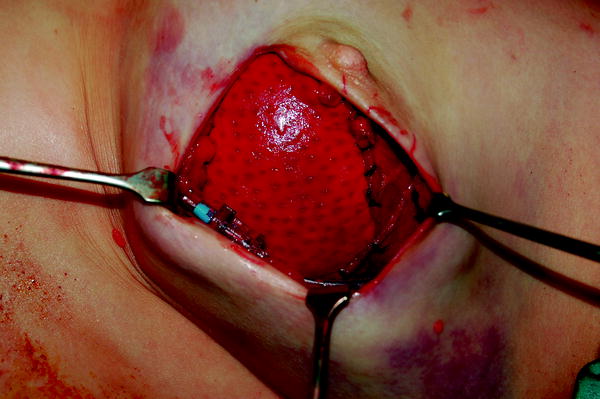

A variety of tissues have been used to cover the lower pole of implants during breast reconstruction (Fig. 6.1). The problem with total muscular cover has been obtaining satisfactory inferior projection and reconstruction of a satisfactory inframammary fold. The tissue matrices in common use include those derived from human skin (Alloderm®), pig skin (Strattice and Permacol) and bovine skin and pericardium [32, 33]. Both synthetic and absorbable meshes have also been used. De-epithelialised lower mastectomy flaps are another option to improve lower pole fullness and provide sufficient cover of the implant where it sits below the lower margin of the pectoralis major muscles (Fig. 6.2). When tissue matrices are used meshes or de-epithelialised skin are used, the pectoralis major muscle is lifted from its site of origin and the tissue matrix, mesh or de-epithelialised flap is stitched between the cut edge of the pectoralis major muscle and the new inframammary fold [33]. This provides a sling for the lower part of the implant alone, Becker implant/expander or tissue expander. The option of de-epithelialising the lower flap of the mastectomy and suturing this to the edge of the pectoralis major muscle is less good at creating an inframammary fold than acellular dermal matrix [34]. The two can be combined to good effect when carrying out a skin-sparing mastectomy.

Fig. 6.1

Strattice® used as a sling for breast reconstruction in a patient having a nipple sparing mastectomy

Fig. 6.2

Bilateral breast reconstruction on the right delayed, and the left prophylactic nipple-sparing mastectomy (following diagnosis of mutation in the BRCA1 gene). Reconstruction was with Strattice®. The patient has a bilateral shaped prosthesis

Complication rates with these various techniques can differ widely. Implant and tissue matrix loss rates can be as high as 15 % [33]. Particular care is needed when selecting the most appropriate incision, especially if a nipple-sparing technique is to be used. Any wound edge necrosis particularly over the tissue matrix or mesh is associated with a high rate of implant loss.