Fig. 4.1

Quadrantectomy (upper lateral quadrant of the right side) specimen orientated by the surgeon with threads indicating the areolar margin (one thread) and upper medial quadrant (two threads)

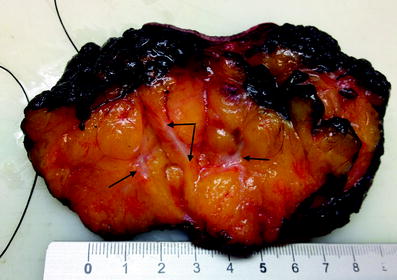

Fig. 4.2

Same specimen as for Fig. 4.1, cut after inking, revealing a tumour with safe margins. The tumour has been cut twice perpendicularly to address the largest diameter

For margins, there are some recent recommendations depending on the type of tumour that should be kept in mind. For invasive cancers, it is sufficient that the ink does not touch the tumour cells to consider the margins as free; for ductal intraepithelial neoplasia, which sometimes shows a discontinuous pattern of growth along the ducts, a margin of at least 2 mm is considered safe; for lobular intraepithelial neoplasia, even if the tumour cells are at the resection margins, this does not require a re-excision [5].

There are several techniques for cutting the specimens, and the technique used depends on the expertise of the pathologist. It is advisable to cut the specimen before the fixation in formalin in order to better appreciate the macroscopic characteristics of the lesion (colour, firmness and consistence) and also to better achieve a suitable size (see later).

The number of samples to be kept from a breast tumour depends mostly on its size. For a tumour up to 2 cm, the entire tumour should be embedded, whereas for larger tumours, although there is not a rule, it is advisable to select at least one sample more for each extra centimetre. Obviously, if there are macroscopically different areas, irrespective of the size of the lesion, all of them should be sampled and embedded.

Crucial is the fixation of the samples: choosing the right fixative, its appropriate volume relative to the specimen size and the time for fixation allows optimal assessment both for simple morphological evaluations and for more complex biological evaluations of the molecular features. The best fixative is formalin because it guarantees the best results from immunohistochemistry (IHC), in situ hybridization (ISH) and molecular analysis of nucleic acids. The appropriate time for fixation differs among laboratories, according to their standardized procedures, but it must be within 6–48 h to prevent subsequent modifications of their own standardized procedures, made to compensate for the artefact due to hyperfixation or hypofixation [6, 7].

4.4 Pathological Features (Size, Type, Grade)

4.4.1 Size

Although assessment of tumour size appears to be a very simple task, it must be done properly. In fact, it is decisive, because it is one of the most important independent prognostic factors [8]. It is essential to take measurements in three planes and not only the largest axis, although the latter will be reported for the pathologic stage. Furthermore, it is advisable to make measurements on fresh tissue in order to avoid the shrinkage effects due to the formalin fixation. Sometimes there may be a discrepancy between the size measured on radiography or ultrasonography and the pathologically (macroscopic and microscopic) reported size: this can be due to the extent of a noninvasive component around the lesion, or the presence of another lesion, even benign, adjacent to the neoplasia that may result in incorrect macroscopic evaluation. In these cases, the measurement must be confirmed on the histological slides and reported as the “maximum histological diameter” in the pathology report. I recommend taking histological measurements even in all those cases where the size is critical for a change in the stage (see later, TNM).

A “microinvasive carcinoma” is defined as a tumour with a largest diameter of its invasive component of up to 1 mm, usually associated with a larger noninvasive counterpart.

For multiple tumours, each nodule should be measured, but the largest one determines the pathological stage. Those cases where multiple foci of carcinoma are present in a larger area of noninvasive tumour are very tricky. As the histological slide is a very thin slice of the tissue and cannot remodel the three-dimensional shape of the tumour, we cannot firmly assert that those foci do not join together in one or more deeper cuts. It would be more accurate to cut the blocks of tissue deeper and deeper, at least on three levels, in order to try to remodel the shape, leaving to the pathologist’s subjectivity and good sense the final consideration of the real size of the infiltrating tumour.

4.4.2 Type

According to the WHO classification [9], breast tumours are divided into epithelial and mesenchymal types. Epithelial ones are more frequent and are further classified into noninvasive and invasive. According to their morphology, both of them are of ductal and lobular type. Amongst the invasive tumours, there are some special types which are different not only on a pure morphological basis, but also reflect a different better or poorer prognosis (see later).

Many authors currently use the term “carcinoma in situ” of ductal or lobular type according to the morphology. Nevertheless, the term “carcinoma in situ” encompasses a wide range of proliferations: potentially neoplastic; surely neoplastic from low grade to high grade; potentially progressing to an invasive carcinoma. They are different from each other not only in their morphological characteristics, but even in their genetic alterations, risk of relapse and likelihood to progress to a frank carcinoma [10]. Instead of the term “carcinoma” for such very different proliferations, it has been proposed to use the term “intraepithelial neoplasia” of ductal or lobular type (ductal intraepithelial neoplasia, DIN; lobular intraepithelial neoplasia, LIN), avoiding the word “carcinoma”, mainly but not only for two reasons: first, just to emphasize that DIN/LIN are not a threat for the life disease; and to protect patients from the devastating psychological effects that the term “carcinoma” may cause [11].

As already said, there are many entities, some of them with unknown (if any) malignant potential, and others with different risk of progression. That may be confusing: for these reasons we suggest changing and unifying this terminology according to [9]. Therefore, we identify as DIN 1A flat epithelia atypia, as DIN 1B atypical ductal hyperplasia, as DIN 1C ductal carcinoma in situ grade 1, as DIN 2 ductal carcinoma in situ grade 2 and as DIN 3 ductal carcinoma in situ grade 3.

For the morphological classification of breast cancer and the list of types and special types, we follow and suggest following the WHO [9], even if in the molecular era it seems useless to characterize breast cancers with traditional morphological terminology. Morphological classification of breast tumours could be interpreted as a vintage occupation of pathologists since the publication of molecular classification based on gene expression profiling [12, 13]. But we should not forget that changes at the molecular level mirror differences at the morphological level, driving the biological and clinical behaviour of breast cancer. Abandoning completely the morphology would result surely in an increase in expense without a significant advantage. For example, tubular carcinoma is a special type of breast cancer, and is well known to have a very good prognosis. We do not need to spend a lot of money to obtain the same information from gene expression profiling. On the other hand, molecular classification identifies some breast cancers with very poor prognosis (the so-called basal-like tumours): unfortunately among those cancers there are some special types, such as adenoid cystic carcinomas, low-grade apocrine carcinomas and low-grade metaplastic carcinomas, which although according to molecular imprinting have a poor prognosis, have a very good clinical outcome. That means that there are some instances where the morphological identification of a special tumour type by itself provides the whole set of information relative to the expected outcome and responsiveness to the therapy, without any need to perform additional investigations, which may indeed be detrimental.

Paget’s disease of the nipple is a very uncommon epidermal manifestation of breast cancer, characterized by infiltration of neoplastic large tumour cells with pale cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent nucleoli in the epidermal layer of nipple–areola complex. It is usually associated with an underlying noninvasive or invasive carcinoma, but it may be found even alone, without any underlying tumour. If it is present, there is no topographic predilection for the tumour, which may be located anywhere in the breast. According to the margin status, the size of the underlying tumour and clinicoradiological presurgical data, patients may be offered conservative surgery combined with breast irradiation instead of mastectomy [14].

4.4.3 Grade

Grading the tumour represents an important issue as it is an important prognostic factor [1]. The universally accepted method for grading breast cancers follows the Bloom and Richardson [15] system, modified by Elston and Ellis [16].

Noninvasive tumours are graded into three classes according to the diameter of the cells, their chromatin, mitotic index and the presence of necrosis.

Even for invasive carcinomas the system classifies the tumours into three classes, according to the formation of tubules, nuclear pleomorphism and the number of mitoses. Although this is an objective system, there are some interobserver and intraobserver discrepancies, due to both the preanalytical phase (type and timing of fixation, which may affect the mitoses and the nuclear shape) and the intrinsic heterogeneity of the tumour (which can alternate being more differentiated areas and less differentiated areas). Whereas extreme grades, G1 and G3, show a very high interobserver consistency, G2 is the most difficult to standardize and has poor reliability when evaluated by several pathologists [17].

4.5 Sentinel Node Biopsy and Lymphadenectomy

4.5.1 Sentinel Node Biopsy

Besides breast-conserving surgery, the introduction of the sentinel node biopsy (SNB) approach to patients was another milestone along the way to conservative treatment of breast cancer [18]. Before the introduction of such a technique, the standard approach was a complete axillary dissection, which provided the information useful to report the nodal status. Unfortunately, this technique, although of great prognostic significance, is of doubtful therapeutic impact, and may also have iatrogenic consequences, such as pain, limitation of movements and chronic lymphoedema of the arm. Fortunately, some clinical trials provided evidence suggesting that SNB is useful in order to avoid an unnecessary complete axillary dissection. Furthermore, it allows one to plan therapy with minimal morbidity for the patient and no impact on the quality of life. Finally, it is able to identify the status of the entire axillary nodes as true negative and may be performed intraoperatively, reducing the discomfort of a double intervention for the patient. Actually, the examination may be performed both during the surgery on fresh nodes, and after the surgery on formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimens. Whatever the method used, it is mandatory that the node is examined entirely until the complete consumption of the tissue to obtain its high negative predictive value. To attain such a result, the node must be extensively scrutinized with a serial sectioning at a very close cutting interval (50 μm), because just a few histological sections represent a minimal part of the entire node, and the less that is examined, the lower is the detection rate of micrometastatic deposits. For both methods, fresh and fixed specimens, IHC can be used in order to better resolve doubts about the nature of the cells. The advantage of frozen sectioning is that the surgery may be done in just one step: in fact, if the node is positive, the patient will undergo axillary clearance in the same operative session.

Another advantage introduced by SNB is the possibility of finding and studying very small metastatic deposits. Currently, according to the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) [19] and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) [20] staging systems, they are subdivided into three categories: (macro)metastases, micrometastases and isolated tumour cells (ITC). Metastases have a largest diameter of more than 2 mm; micrometastases range between 2 mm and 0.2 mm; ITC are little clusters of tumour cells up to 0.2 mm in largest diameter. The ITC definition is not only on the basis of size, but also includes their morphological behaviour: they “don’t show evidence of metastatic activity”, which means proliferative activity, stromal reaction and penetration of vessel sinus walls [19, 20]. This definition emphasizes the scarce knowledge of their actual behaviour and their prognostic significance.

To standardize those cases, mostly metastatic lobular cancers, where the cells are not in strict contact with each other, creating severe difficulties in linear measurement, it has been proposed to consider as ITC cases where there are clusters of up to 200 cells in a unique histological cross-section [19, 20].

4.5.2 Lymphadenectomy

Lymphadenectomy specimens ought to be accurately examined macroscopically in order to retrieve all the nodes, even the smallest ones. The nodal status is an important and essential part of the staging system and the more nodes that are histologically examined, the higher is the likelihood of finding (micro)metastasis. Furthermore, for the same reason, each node from a lymphadenectomy sample, if negative, should be cut into more sections (from three to six) in order to obtain more accurate information on the nodal status. According to the TNM staging system [19, 20], the nodal stage depends on the number of metastatic nodes when at least a single node is found to be (macro)metastatic. In such cases, even if in the other nodes there are only micrometastases, the stage changes according to the number of metastatic nodes, irrespective of the size.

Conversely, if the nodes are only micrometastatic, the number of metastatic nodes does not affect the stage.

4.6 Staging

A further step in the pathway after breast cancer diagnosis is to establish the extent of the disease and to formulate the prognosis, separating patients into distinct categories in order to choose the appropriate therapy. The task pertaining to pathologists is the pathological stage, usually obtained according to the UICC/AJCC TNM staging system [19, 20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree