Chapter 21 Bodylifts and Post Massive Weight Loss Body Contouring

Summary

Introduction

There has been a tremendous surge in excisional body contouring procedures in recent years fueled by the growing obesity epidemic and the success of weight-loss surgery. In the USA, obesity is a major problem and its incidence is increasing worldwide.1–3 The potential benefits of substantial weight loss, most notably, a reduction in obesity-associated morbidity, such as hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis, has grabbed the attention of public health agencies. While medical weight-loss methods often prove difficult and ultimately unsustainable, bariatric surgical procedures are now recognized as a more reliable method of weight loss for morbidly obese patients.4–6 The demand for bariatric surgery is expected to rise as long as no alternative treatment for morbid obesity exists.7 As a result, the number of patients seeking surgery to remove or reposition redundant skin and tissues is expected to increase proportionally. Data from 2006 reveal that 65 000 massive weight loss (MWL) patients underwent body-contouring procedures.8 As the scope and magnitude of body contouring procedures increases each year, the plastic surgeon must pay close attention to issues of patient safety.

Evaluation of the Massive Weight Loss Body Contouring Patient

MWL patients often present with a variety of deformities, based on their initial body-fat distribution. While some may have a preponderance of truncal excess, others may exhibit significant lower-extremity deformities. An overall assessment of the patient should be made taking into account the distribution of the skin laxity, remaining adiposity, rolls, folds, skin tone, integrity, scars, abdominal-wall structure (rectus diastasis, hernias, thickness), and overall constitution (i.e. poor mobility, chronic pain, stigmata of malnutrition). With the patient standing in front of a mirror, the surgeon may demonstrate possible improvements that can be achieved with resection by manually pinching and repositioning tissues. Asymmetries should be noted to the patient and documented. Standardized photographs of the patient should be taken prior to surgery from multiple angles to document preoperative deformities. A surgical plan for patients with multiple contour irregularities must then be developed. The Pittsburgh Weight Loss Deformity Scale is a useful tool to help describe the deformities observed and help plan what procedures are needed for a given deformity.9

The key factor in optimizing results, limiting complications, and maximizing safety in the body-contouring population is patient selection. Patients typically present for body contouring at least 1 year after gastric bypass surgery and should be weight stable for at least 3 months. Their BMI should be favorable, with current literature suggesting that a BMI >35 may result in an increased risk of surgical complications.10,11 Patients with a BMI of >35 should generally lose more weight before obtaining surgery. Exceptions to this rule include a true giant disabling pannus or chronic panniculitis, conditions for which a functional panniculectomy would be indicated. A favorable BMI, however, does not always predict appropriate nutritional status and may not represent an ideal patient for body contouring. Medical and psychosocial issues should be fully evaluated and optimized. Patients should have realistic expectations and goals. Financial issues should also be taken into consideration, including allowing adequate time out of work for recovery. Many patients may be disappointed that they have not reached an appropriate BMI, nutritional status, or other preoperative criteria. Encouragement and reassurance can motivate them to work on these issues and follow-up for another consultation.

Hernias are common in patients who have had previous open abdominal surgery. Consideration should be given to planning a team case with the bariatric surgeons. Body-contouring operations can be performed at the same time as hernia repairs, however, the length of the body contouring procedures should take into consideration the magnitude of the hernia and potential operative time needed to repair the hernia appropriately.12 Patients presenting for hernia repair, or lower body lifts that require position changes, may benefit from preoperative bowel preparations, thereby decreasing risk of intraoperative contamination and postoperative discomfort.

Surgical Technique

Variations of abdominoplasty for the weight-loss patient

The abdomen is perhaps the area of most concern for patients who seek body contouring. While a thorough discussion of abdominoplasty is presented in Chapter 20, we will cover some variants of the procedure relevant to the MWL patient. As early as 1899 and again in 1910, Dr Kelly described his experience with the transverse resection of the pendulous abdomen.13 This work led to the modern abdominoplasty as we know it today,14,15 which has been largely considered to be a cosmetic operation. For the MWL patient, however, the abdominal pannus is often the source of functional problems, with difficulty ambulating or intertrigo. In this patient population, abdominal contouring has both cosmetic and functional components. The degree of cosmetic impact will depend primarily on the ability to perform additional undermining, plication, and umbilical transposition safely. In general, patients with a higher BMI and/or patients with higher medical risk will undergo a functional panniculectomy. In its simplest form, an elliptical excision of the pannus is performed with little or no undermining outside the area of resection. The umbilicus is usually sacrificed, and no plication is performed. At least two Jackson-Pratt drains are placed. The authors prefer a closure consisting of interrupted 2–0 polypropylene vertical mattress sutures with the knots placed superiorly. The sutures are spaced every 1–2 cm to ensure eversion of the wound edges and add strength to the closure, and skin staples are placed to approximate the skin edges. This closure technique has proven very secure, with a low rate of wound dehiscence. If there is active panniculitis, the staples are left out and gauze wicks are inserted between the mattress sutures. These are removed in 48 hours.

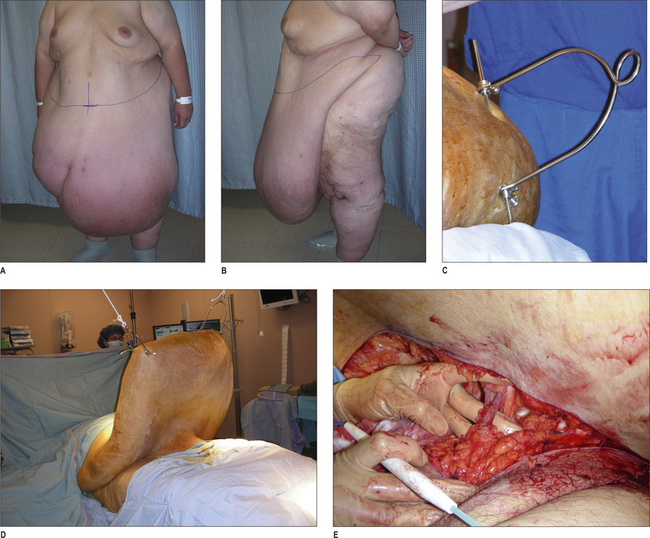

A variant of the functional panniculectomy is management of the ‘giant pannus’. This condition involves a pannus so large that ambulation and activities of daily living are severely hampered. A true giant pannus is not a very common entity, and is most often seen in patients who start the bariatric surgery process at an extremely high BMI and, despite significant weight loss, may still have a BMI that is in the severely obese range. While most severely obese patients are best treated with panniculectomy when their BMI is much lower, the functional impairment of the giant pannus can warrant the risk of surgery. To facilitate the operation, the pannus is suspended from ceiling bars or hydrolic lift using orthopedic pins and traction bows (Fig. 21.1). This allows venous blood to drain from the pannus prior to the procedure, prevents the pannus from resting on the patient’s chest during the procedure (which can impair ventilation), and enables better exposure and control of the impressively large blood vessels that will be encoun-tered. The wound closure is as described above for the functional panniculectomy.

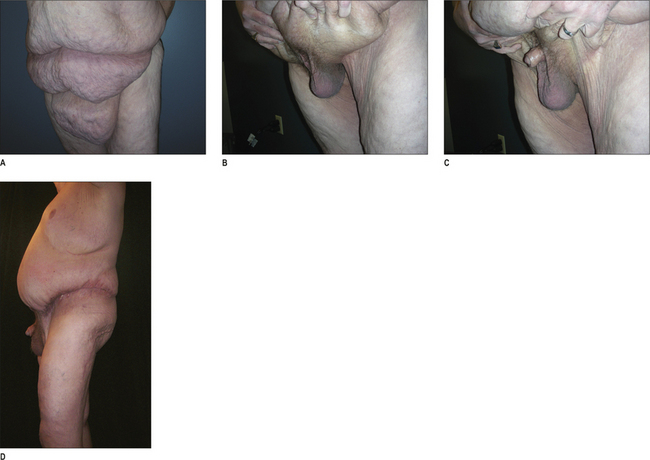

Another variant of the functional panniculectomy is correction of the buried penis (Fig. 21.2). In this syndrome, the penis is invaginated within the pannus. It may be possible to manually extract the penis, or there may be a tight cicatrix on the pannus that prevents this maneuver. In the latter case, it is useful to have an urologist available when the scar tissue is released in case there is unexpected pathology and/or difficulty releasing the contracted penis and scrotum. Once the penis is manually extracted from within the pannus, the panniculectomy can be commenced superior to the genital region. It is usually necessary to secure the tissues above the genital region to the abdominal wall in a manner similar to the mons-plasty described below.

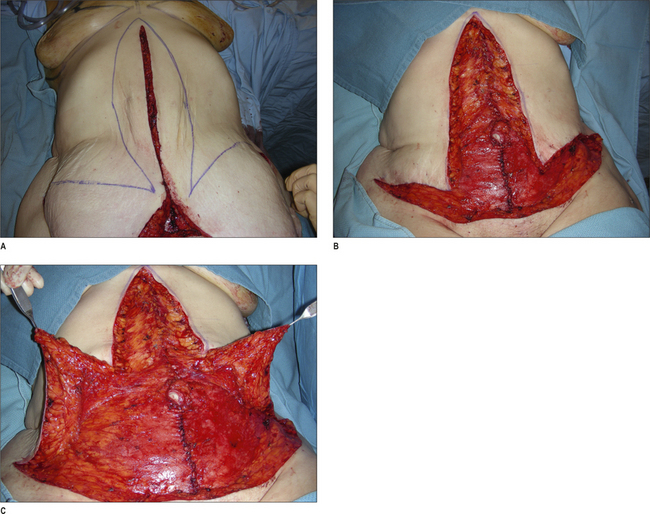

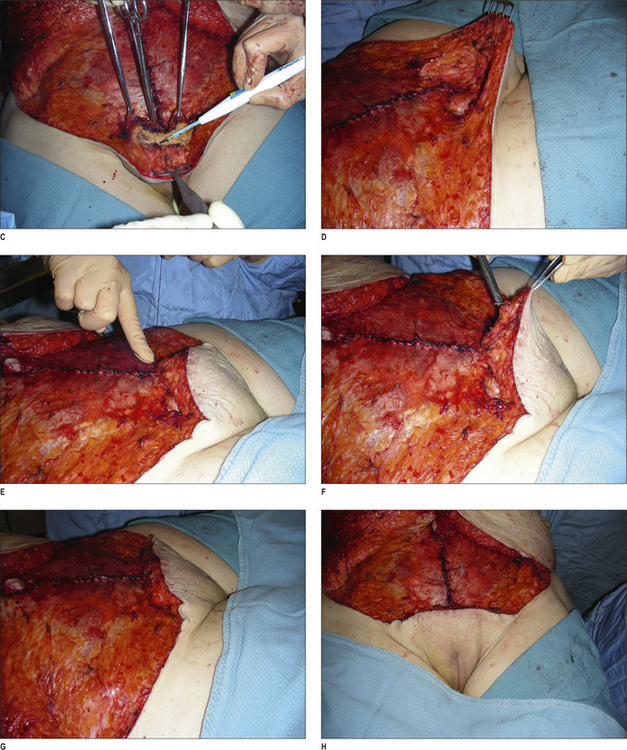

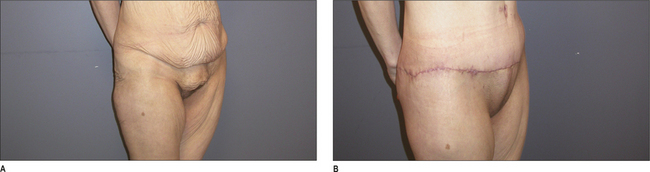

An evolution of the abdominoplasty procedure includes the addition of a vertical scar to eliminate horizontal excess, which is often necessary in the MWL patient.16,17 Patients with significant epigastric skin excess are willing to accept a new vertical midline scar in exchange for improved contour. Although a less desirable approach, patients reluctant to commit to the vertical scar can still have the vertical resection done in a second stage if they are not satisfied with the results of a transverse only abdominoplasty. The key to performing this procedure safely is to limit undermining of the tissues outside of the area of resection (Figs 21.3–21.5). Specifically, the authors advocate not undermining to the costal margin. We have found that preservation of these perforating vessels in the upper abdomen will decrease the risk of wound complications. Patients are advised that there is a higher risk of wound-healing problems compared with a standard abdominoplasty. Additionally, great care is taken to avoid excessive tension on the ‘triple point’, or confluence of scars on the lower abdomen. This is best accomplished by first resecting tissue in a horizontal axis as with the standard abdominoplasty procedure. The horizontal wound is then approximated with sharp towel clips. Next, the vertical resection is marked with the transverse wound approximated. When insetting the umbilicus in a vertical abdominoplasty incision, minimal if any cutout should be created for the umbilicus. With lateral tension and time, this will naturally widen to good shape. If a circular incision is made at the site of the umbilicus inset at the time of initial operation, this will widen to an undesirable horizontally elongated shape.

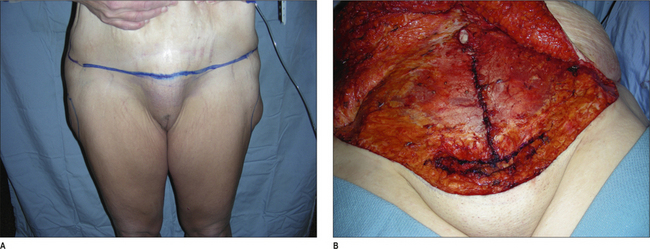

Monsplasty

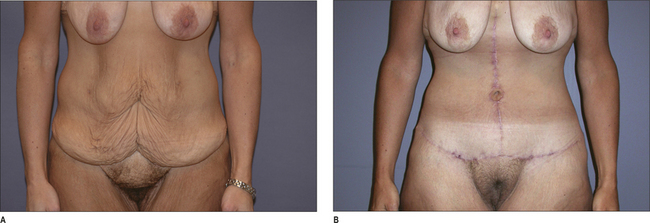

Correction of mons ptosis and fullness is a necessary adjunct to abdominal contouring in a high percentage of MWL patients. The mons can be thinned to match the upper abdominal flap and elevated using suture to restore a youthful contour. Failure to correct the mons during an abdominoplasty or lower body lift can lead to an unsatisfactory result, despite adequate correction of the abdomen, thighs, or buttocks. During the abdominal-contouring procedure, the incision for the lower margin of resection should be placed 6 cm above the anterior vulvar commissure with the tissues on upward stretch (the line of incision should come just above the pubic symphysis, and may need to be marked slightly higher than 6 cm). This will help restore the proper proportions for the pubic hairline. In order to properly reshape this region, two specific steps are contemplated. One consideration is for the suspension of tissues to the abdominal fascia. The second consideration is reduction of the thickness of the mons. The authors have found that liposuction, when used to thin the tissue of the mons, results in prolonged edema and an unpredictable result. We have had good success with direct defatting of the tissue of the mons. The thickness of adipose tissue to be resected is estimated and marked. This is based on the thickness of the abdominal flap in relation to the desired thickness of the mons region. Next, the deep adipose tissue is retracted with three Allis clamps and skin retractors placed on the anterior surface. Using the electric cautery, a wedge resection of the adipose tissue is performed with the dissection terminated at the pubic symphysis. Great care is taken to avoid entering the vaginal vault. This technique results in a uniform thinning of the mons region. With or without this initial reduction in thickness, the mons can then be suspended to the abdominal wall fascia. Three to five sutures are placed from the deep layers of the mons superficial fascial system (SFS) into the abdominal wall fascia using either 2–0 or 0-braided nylon. This technique has resulted in durable results with a high degree of patient satisfaction (Figs 21.6 & 21.7). We have encountered no incidences of sexual dysfunction; quite the opposite in fact, patients are so pleased to have this region rejuvenated that they report an improvement in their sexual function. Patients are warned that the angle of the urine stream may be changed temporarily because of the pull on the mons tissues.

Lower-body lift

Correction of the abdomen alone is often not enough to restore appropriate contour for many MWL patients. Procedures have been devised to correct the entire lower-body unit, including the lower-body lift, belt lipectomy, and circumferential torsoplasty.18–21 Although the names are different, the principle in theory is similar; to affect a circumferential correction of laxity in the buttocks, lateral thighs, and abdomen with elimination of rolls and festoons.22 Lockwood popularized the lower-body lift, and made many important contributions to this field including the repair of the superficial fascial system.23 Further enhancements of outcomes have resulted from autologous augmentation of the buttocks with lower-body lift procedures.24,25 Fat can be preserved from the posterior resection based on gluteal artery perforators, deepithelialized, and rotated into pockets over the gluteal muscles to give shape to a region that otherwise becomes flattened with routine lift procedures. For the abdomen, the fleur-de-lis can be added concomitantly if laxity remains in the horizontal vector.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree