Benign Neoplasms

Kathleen Haycraft

Practitioners must be familiar with the normal before they are capable of identifying the abnormal. Essential dermatology knowledge and skills are imperative to diagnose benign lesions and to prevent both over diagnoses and misdiagnoses. Proper evaluation and diagnosis of any lesion can be key to identifying underlying systemic disease.

Patients often seek advice from their primary care provider for the evaluation and treatment of skin lesions. Some are concerned about malignancy, while others are distressed by their cosmetic appearance or symptoms. This chapter addresses benign neoplasms that are common. Despite reassurance that they are benign, many patients wish to have these lesions removed. The desire to treat benign lesions needs to be balanced with the potential for undesirable cosmetic outcomes.

The management and follow-up care for most benign neoplasms are similar unless noted otherwise in the topic discussion. Diagnosis of common neoplasms is usually a clinical one unless there are any suspicious features concerning to the clinician. If a biopsy is indicated, the appropriate technique should be selected based on the type, number, and location of the lesions. Once a diagnosis is made, management options should be discussed in detail with the patient. Clinicians should consider many variables about the patient and disease when performing elective procedures to remove lesions.

Patient education regarding benign lesions is always important and should emphasize the signs and symptoms of skin cancer, including sudden changes or the development of abnormal features. Symptoms of sudden and irregular growth, ulceration, pain, bleeding, or red or blue color changes should prompt the clinician to reevaluate the lesion and perform a biopsy as indicated. Although most diagnoses and management of benign lesions can be done by primary care, collaboration or consultation with a dermatologist may be considered. Clinicians who are unsure of the diagnosis, have difficulties with biopsy interpretation, or are inexperienced in procedural skills for treatment or removal should make a referral to a dermatologist.

SEBORRHEIC KERATOSIS

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is the most common benign cutaneous tumor. They are associated with senescence and have some genetic correlation. Synonyms include seborrheic verruca and senile warts. The plural of SK is seborrheic keratoses.

Most individuals will have at least one SK in their lifetime. Seborrheic keratoses occur at any age; however, the frequency increases in the mid- to later decades of life. They are one of the most common reasons that prompt individuals to seek evaluation for a suspicious skin lesion. There is no gender preference and reduced prevalence in darker skin. SK may occur after an erythrodermic drug eruption, erythrodermic psoriasis, or exfoliative erythroderma.

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of SK is not known. Although frequently referred to as “wart-like lesions,” SKs are not related to a virus. They have been linked to mutations in the FGFR3 and P13K genes. Changes occur in the epidermis and are associated with histologic evidence of proliferation of the basal keratinocytes with associated apoptosis.

Clinical Presentation

SKs have a wide range of appearances and can occur anywhere on the body. They are primarily distributed on the face, chest, back, and arms. The color of SKs can range from tan to dark brown or even black, which can mimic the appearance of melanoma. The most common history and presentation is a slowgrowing, waxy, and rough-textured plaque that crumbles. Older generations often referred to them as “barnacles” as they can sometimes be scraped off. In the early stages of development, the lesion may be small and smooth, whereas in the later stages, SKs may become elevated, enlarged, and darker in color. Some have a wart-like appearance due to the presence of keratin that deposits, called horny pearls or pseudocysts. Typically, SKs are asymptomatic but can become extremely pruritic and irritated, especially in areas of friction such as the inframammary folds or the bra area.

Due to the variety of clinical presentations, it can be difficult to differentiate an SK from a benign wart or malignant nodular melanoma. Therefore, careful examination of SKs is important so that benign lesions are not unnecessarily biopsied and possible malignant neoplasms are not overlooked. In some rare cases, melanoma can arise in an established SK. The patient may report a new onset of itching, bleeding, pain, or color changes, which should not be disregarded even if the lesion has been present for years.

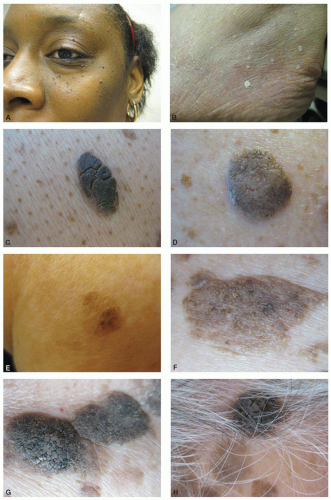

It can be helpful to use an otoscope or dermatoscope to gain a closer visual examination of the lesion. Subtypes of SKs can have classic features that provide diagnostic clues (Figure 11-1).

Dermatosis papulosa nigra is a subtype of SK that occurs in skin of color, primarily on the face and at an earlier age. The dark brown papules vary in size from pinpoint to a few millimeters.

Stucco keratoses (barnacles) are subtypes of SK that are numerous light brown to white in color scaly papules that are distributed on the tibia, ankle, and feet. Stucco keratoses have an appearance of being “stuck on.” They are more frequent in Caucasians and exacerbated by excessive UVR exposure.

Pigmented SKs occur as the proliferating keratinocytes trigger neighboring melanocytes, resulting in increased melanin in the SK and resultant darker appearance.

Reticulated SKs are seen on sun-exposed skin and visibly have a variation in color and ridge patterns. They have been postulated to develop from solar lentigo.

Cerebriform SKs appear to have sulci and ridges similar to the brain.

Multiple SKs may interfere with the examiner’s ability to identify underlying cutaneous malignancies.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Seborrheic keratosis

Actinic keratosis

Basal cell carcinoma (especially pigmented)

Squamous cell skin carcinoma

Melanoma

Wart

Intradermal nevus

Sebaceous nevus

Prurigo nodularis

Acrochordon/skin tag

Management

SKs are benign and do not require treatment. Patients may request treatment for cosmetic reasons or for symptomatic relief from pruritus, irritation, or tenderness. The preferred method is cryotherapy for smaller and thinner lesions. Patients should be warned that SKs may need more than one treatment and can recur. Care must be taken as aggressive cryotherapy may result in hypopigmentation or scar that can appear more disfiguring than the SK. Thicker or larger SKs may be handled more easily with shave excision. Ammonium lactate and α-hydroxy acids have been shown to reduce the appearance of SKs.

Prognosis and Complications

SK can be disfiguring, especially if they involve the face or large and dark lesions. Their appearance can make individuals self-conscious, lower their self-esteem, and be perceived as a sign of aging. Complications occur if a malignancy is missed or treatment is overly overaggressive. Patients who “pick” at their lesions may develop secondary infections.

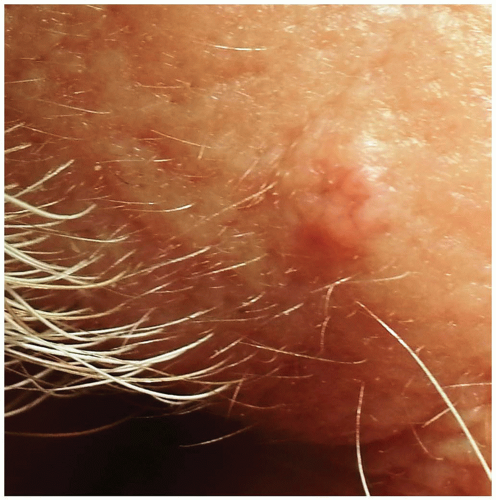

The Leser-Trélat sign is a rare but sudden eruption of numerous SKs that precedes, accompanies, or follows an underlying malignancy (Figure 11-2). There is no evidence to support this phenomenon, yet most clinicians consider it to be a reliable indicator. Until definitive data can support or reject Leser-Trélat, primary care providers should ensure that the patient has completed age-appropriate screening examinations and other diagnostics indicated from the patient history and physical.

SEBACEOUS HYPERPLASIA

Pathophysiology

Enlarging sebaceous hyperplasia (SH) is a common disorder of middle-aged adults where the sebaceous gland is enlarged. Histologically, there is an increased number of basal cell and superficial sebaceous lobules surrounding a dilated pore or follicle. They are thought to be related to levels of circulating androgens, yet studies do not support a gender preference. Other variables include excessive sun exposure or other forms of radiation. SH has a higher incidence with aging, in transplant patients, and in pregnancy. Immunosuppressed patients treated with cyclosporine are also at increased risk for developing SH.

Clinical Presentation

SHs usually present as soft, yellowish, 2- to 3-mm papules occurring as single or multiple lesions on the face (predominately nose, cheeks, and forehead). Lesions have a central dell (umbilication) surrounded by “crown vessels” (Figure 11-3). The vessels occur in an organized manner on the outer rim and not in the dell. This is compared to the erratic pattern blood vessel usually found across the center of a basal cell carcinoma. The lesions are soft to palpation in contrast to basal cell carcinoma, which tends to be firmer with erratic pattern of telangiectasia across the central area. Some individuals state that they express the lesion’s contents upon squeezing.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Sebaceous hyperplasia

Acrochordon

Benign nevi

Acne

Basal cell carcinoma

Milia

Wart or molluscum

Sebaceous adenoma

Sarcoidosis

Syringomas

Trichoepithelioma

Xanthoma

Management

In most cases, SHs do not need to be treated. If they are widespread, disfiguring, or diffuse, several therapies may be implemented. It is important to note that the lesions will frequently recur after discontinuation of therapy. Isotretinoin should only be used by experienced dermatology practitioners who are knowledgeable about the medication and registered with iPLEDGE, the federally monitored information and restricted distribution program. Phototherapy (with combined use of 5-aminolevulinic acid or PUVA) can be helpful in some cases. All of the above treatments are considered off label and will not likely be covered by health insurance.

A wide variety of destructive agents may be utilized, including phototherapy, laser treatment, cryotherapy, cauterization or electrodesiccation, topical chemical treatments (bichloracetic acid or trichloroacetic acid), and shave excision. Destruction of SHs may result in atrophic or ice pick scarring or changes in pigmentation (transient or permanent) that may be less desirable than the original lesion.

Special Considerations

SH can occur in newborns and is not a cause for alarm. Oral retinoids and tazarotene should not be used in childbearing females without the necessary birth control methods and monitoring through iPLEDGE. Both are category X in pregnancy.

SYRINGOMA

Pathophysiology

A syringoma is a benign adnexal (eccrine sweat gland) tumor located in the superficial dermis with numerous ducts embedded in a sclerotic stroma.

Clinical Presentation

Syringomas present as flesh-colored, translucent, or yellow papules. There are several subtypes, but most are small (often 1-3 mm) papules located on the eyelids, axilla, umbilicus, or vulva. Syringomas are more common in women and have an onset around puberty (Figure 11-4). Most are asymptomatic, but patients may report pruritus. Patients can be distressed by their appearance and seek treatment for cosmesis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Syringoma

Basal cell carcinoma

Cutaneous tuberculosis

Sarcoidosis

Granuloma annulare

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma

Milia

Sebaceous hyperplasia

Steatocystoma

Trichoepithelioma

Xanthelasma

Management

Treatment is not necessary for these benign tumors. If requested for cosmetic enhancement, modalities to treat syringomas may include scissor excision, electrodesiccation, electrocautery, laser, cryotherapy, trichloroacetic acid, dermabrasion, topical retinoids, and oral isotretinoin (not FDA approved). The size, location, and number will influence the type of modality employed.

Clinicians should heed a word of caution if attempting to treat syringomas prominently located on the patient’s face, often close to the lid margin. Remember, if the syringoma is visibly obvious, so will any resulting scar, abnormal pigmentation, or complication that results from your treatment. As always, an experienced clinician in the procedure should perform treatment of benign lesions for cosmetic purposes. Preauthorization for the procedure with the patient’s insurance company is advised as coverage for the procedure varies significantly.

Prognosis and Complications

Syringomas are benign, but in rare instances, they are associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and Down syndrome. Syringomas of the scalp can produce scarring alopecia. These lesions may affect self-esteem and body image, especially at puberty.

SKIN TAGS

Acrochordon, also called skin tag or fibroepithelial polyp, are benign but annoying lesions that frequently prompt patients to come to your office. Everyone hates the appearance and feeling of skin tags! The plural form is acrochordia.

Pathophysiology

Histologically, skin tags are a fibrovascular papule covered by normal epidermis. Skin tags have been linked to HPV types 6 and 11; however, it is not known if this is pathogenic or opportunistic. Nearly half of the population has skin tags. They are uncommon in children and increase with age. There may be some familial predispositions. They have a predilection for females more than males, and are significantly increased in the morbidly obese and patients with metabolic disorders.

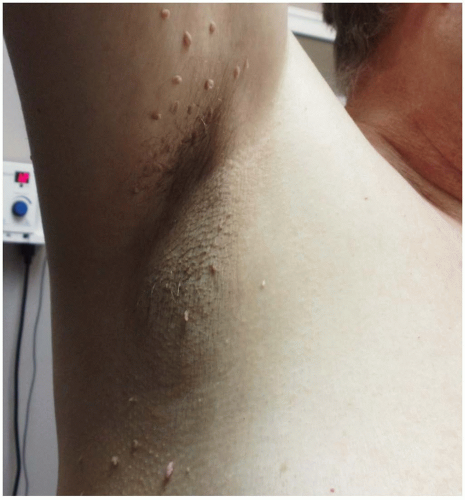

Clinical Presentation

Skin tags are small, soft, pedunculated (atop an elongated stalk) papules that favor the skin folds. They are commonly located in areas of friction including the neckline, axilla, inframammary and inguinal

folds, and eyelids. They may be hyperpigmented or flesh color and vary in size from 1 to 8 mm. Secondary changes include inflammation, hemorrhagic crust from trauma or friction, and necrosis from torsion (Figure 11-5).

folds, and eyelids. They may be hyperpigmented or flesh color and vary in size from 1 to 8 mm. Secondary changes include inflammation, hemorrhagic crust from trauma or friction, and necrosis from torsion (Figure 11-5).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Skin tags

Neurofibroma

Melanomas (may develop at the base)

Premalignant fibroepithelial tumor (Pinkus tumor)

Seborrheic keratoses

Verruca, genital and nongenital

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of skin tags is a clinical one. Biopsy may be indicated if there are any suspicious features. Additionally, if multiple tags are present, a thorough history and physical should be performed to rule out any underlying metabolic abnormalities. Practitioners excising skin tags should be cautioned against discarding the tissue (skin tag) without sending it to pathology. While it may be an additional cost to the patient, the clinician should ensure that they have not overlooked a malignancy.

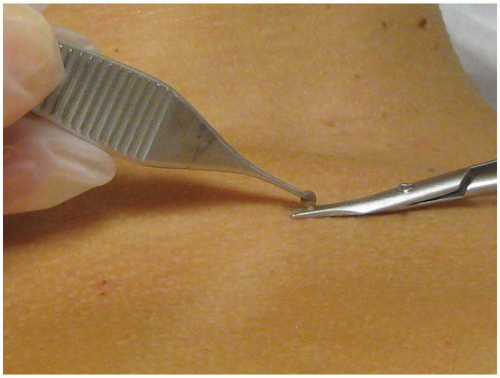

Management

Skin tags do not require treatment but can be removed if pruritic, painful, or irritated. Management modalities include electrodesiccation, scissor excision (clipping), ligation, and cryotherapy (Figure 11-6). Over-the-counter products containing salicylic, retinoic, or carbolic acid, coal tar, and “natural” ingredients are available. Popular do-it-yourself products promoted on the internet and television entice patients to use homeopathic or “quick” fixes for patients tired of living with these ugly lesions. Ligation of a skin tag, by tying it at the base with string or dental floss, is an old-fashioned remedy. Patients sometimes use an abrasive tool or body scrub to exfoliate the papules when they are small. Brave patients tired of the lesions have been known to use nail clippers or scissors and cut them off themselves. Often these treatments result in only partial resolution, severely inflamed lesions, or secondary infections, which prompts the patient to visit your office for complete resolution.

Prognosis and Complications

Although they are benign, skin tags can become symptomatic, including irritation, pain, and bleeding usually from clothing, jewelry, or necklace. Torsion sometimes occurs and results in necrosis, with the papule turning black and falling off. Most importantly, misdiagnosis of a skin tag could be melanoma and basal cell carcinoma.

FIBROUS PAPULES

Pathophysiology

Fibrous papules are a harmless type of angiofibroma without a known cause. Histologically, there is fibrosis surrounding blood vessels or adnexa. Some consider it a type of nevus.

Clinical Presentation

Fibrous papules are firm, dome-shaped papules that usually occur on the lower portion of the nose and occasionally on other areas of the face (Figure 11-7). They are almost always a solitary lesion but occasionally present as multiple papules on the face. Fibrous papules are flesh, red, or pink color and may have hair protruding from the lesion. Clinically, they can be difficult to differentiate from an early basal cell carcinoma. Multiple fibrous papules or angiofibromas in a butterfly distribution of the face may be a clinical manifestation of tuberous sclerosis and prompt further evaluation.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Fibrous papules

Basal cell carcinoma

Melanocytic nevus

Ruptured hair follicle

Management

Treatment is not necessary for these fibrous papules, but may be performed for symptomatic or cosmetic reasons. Curettage or shave removal can be considered, but may result in a scar and the lesion may recur. Excision may also be performed and has better cosmesis and less likelihood of recurrence.

Prognosis and Complications

If treated, patients should be advised regarding scars and recurrence.

NEUROFIBROMA

Pathophysiology

The cell of origin of neurofibromas has not been isolated. Perineural fibroblasts synthesize collagen and create a network that wraps around the nerves and associated Schwann cells. There are two types of neurofibromatosis associated neurofibromas, which are discussed in chapter 6.

Clinical Presentation

In adults, solitary neurofibromas are soft fleshy papules that are usually flesh color to pinkish white. They can vary in size from a few millimeters to centimeters (Figure 11-8). Button-holing may be present (pressure with your finger may invaginate the lesion). Multiple neurofibromas presented in childhood should be evaluated for neurofibromatosis (Figure 11-9).

Management

When one or two lesions are present, they are usually spontaneous lesions without systemic significance. Treatment may be considered if a neurofibroma is symptomatic or is cosmetically undesirable. Surgical excision and CO2 laser may yield the best results. Shave excisions can leave large scars and a higher risk for recurrence.

PRURIGO NODULARIS

“Picker’s nodules” (PN) or Hyde nodules, are benign lesions that can be one of the most challenging skin conditions for clinicians to manage. Considered by most to be a neurodermatitis, PN has a higher incidence in patients with atopic dermatitis, HIV, hepatic disease, anemia, renal disease, celiac disease, insect bites, stress, and lymphoproliferative disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree