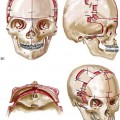

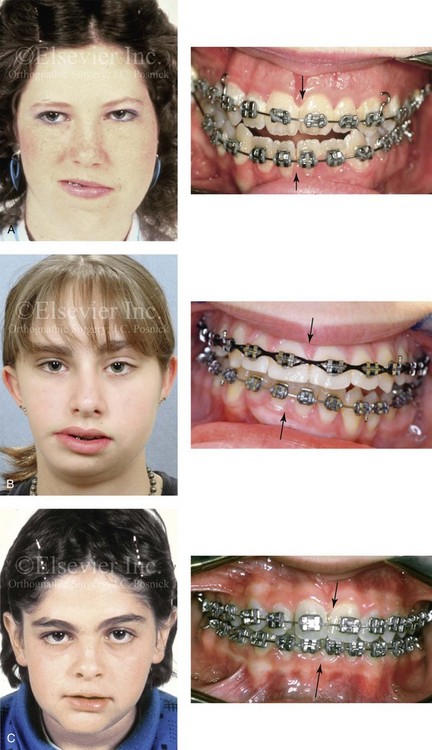

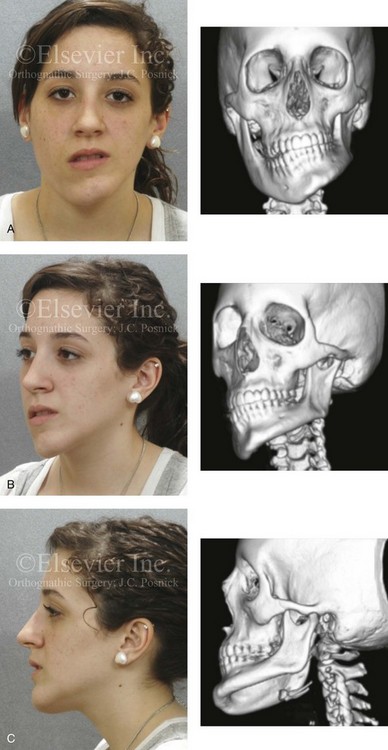

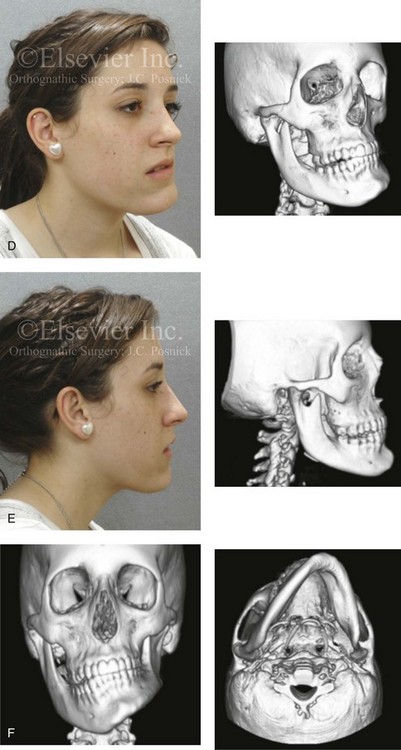

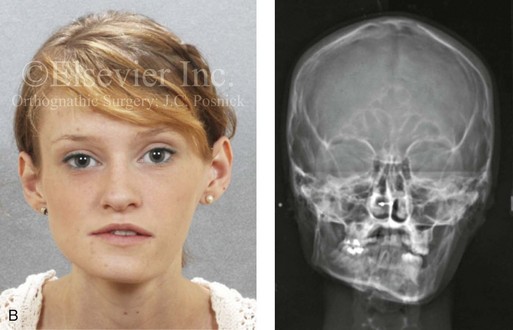

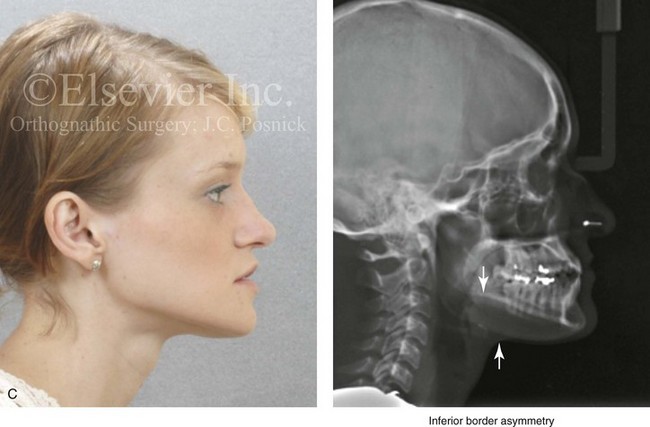

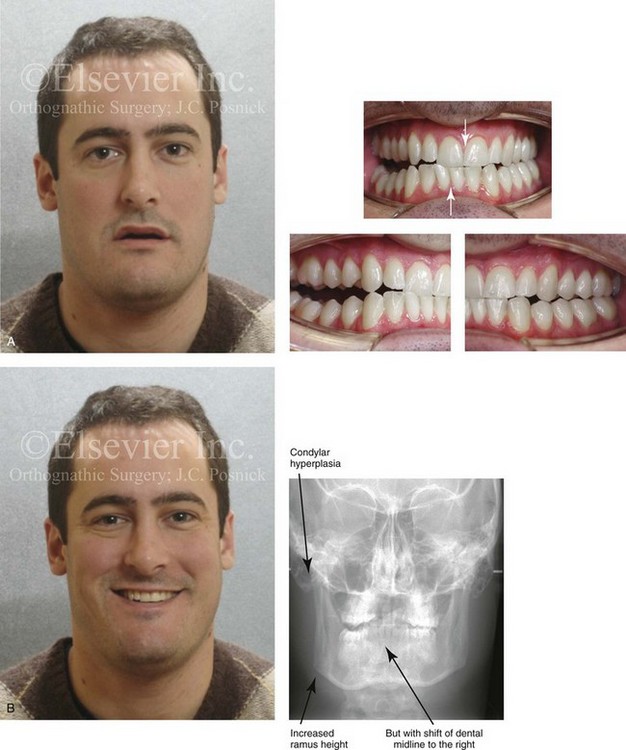

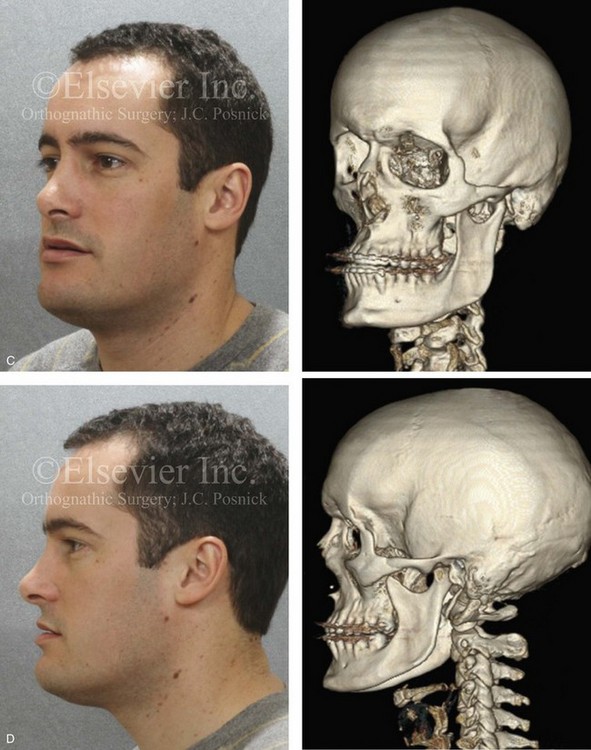

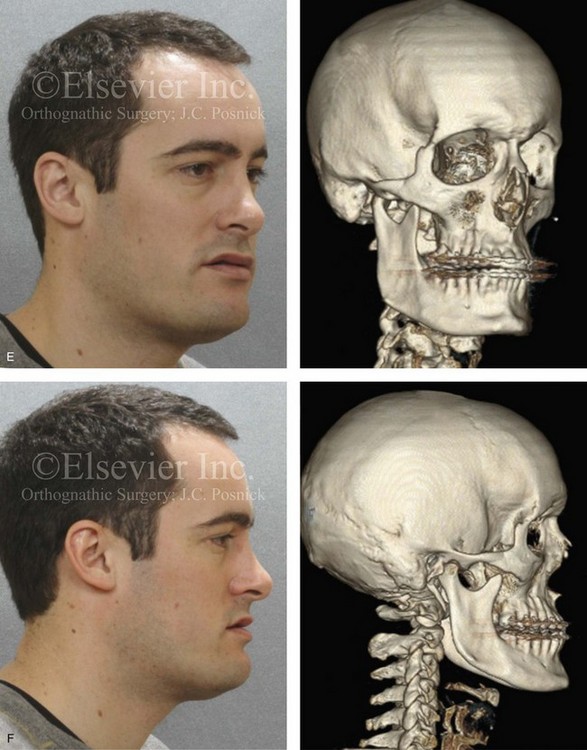

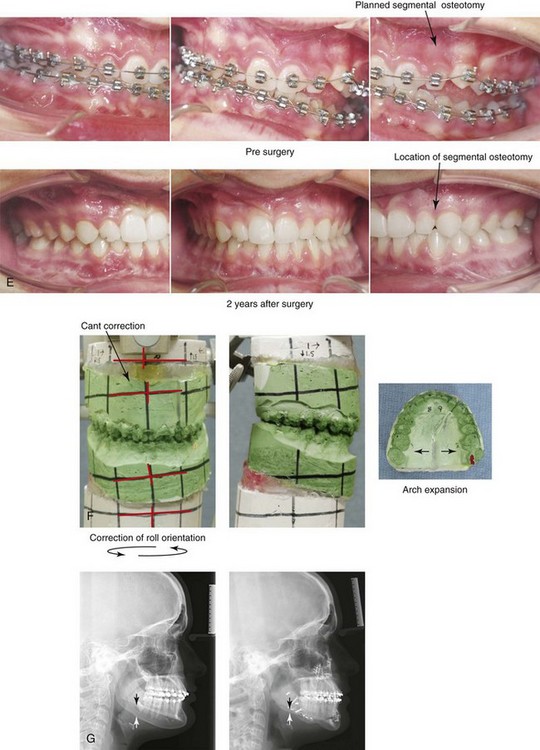

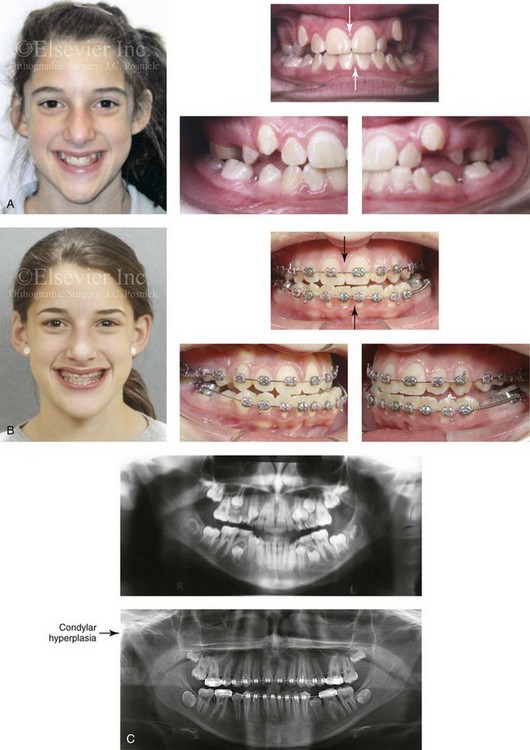

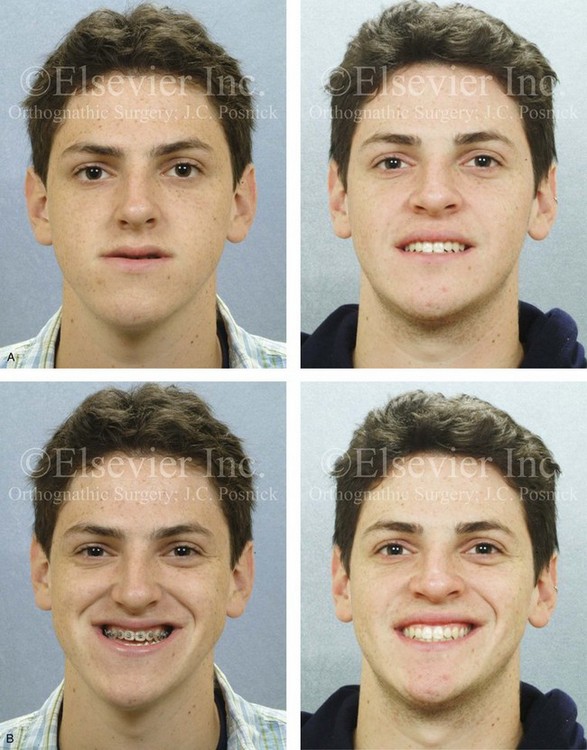

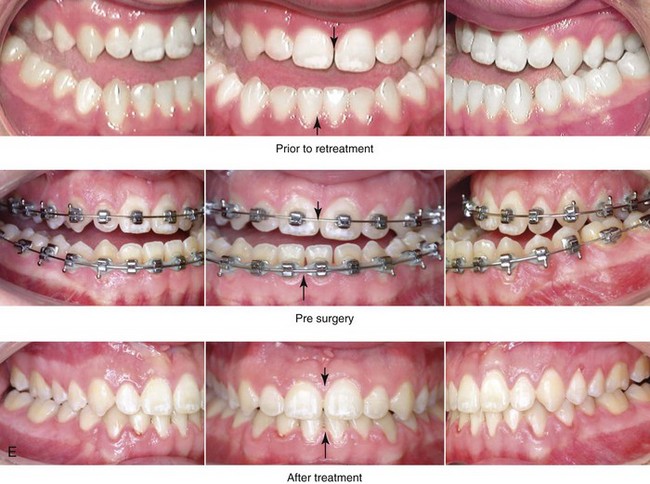

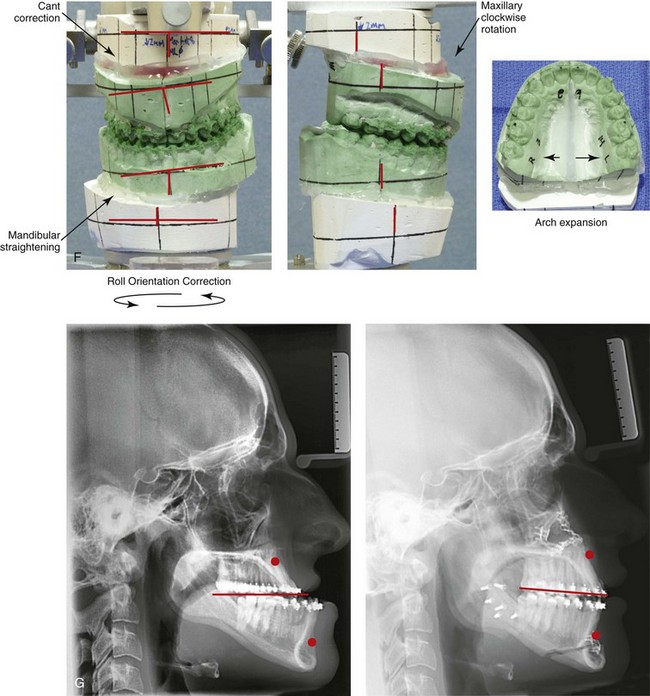

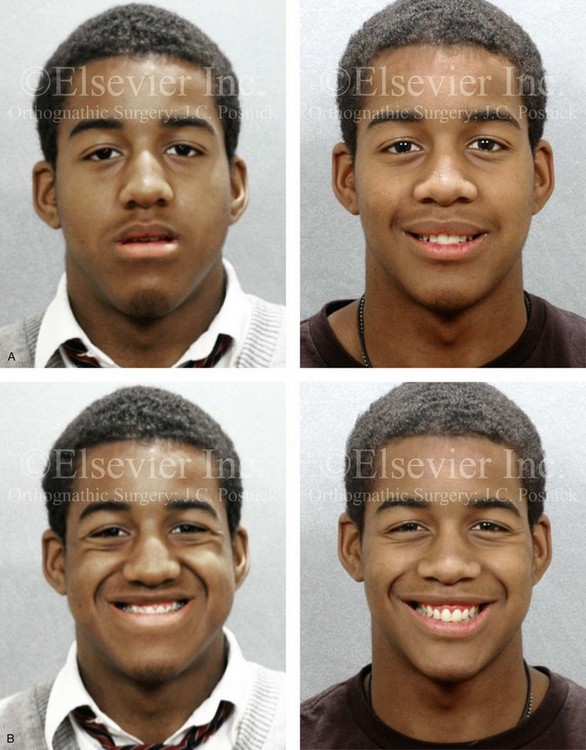

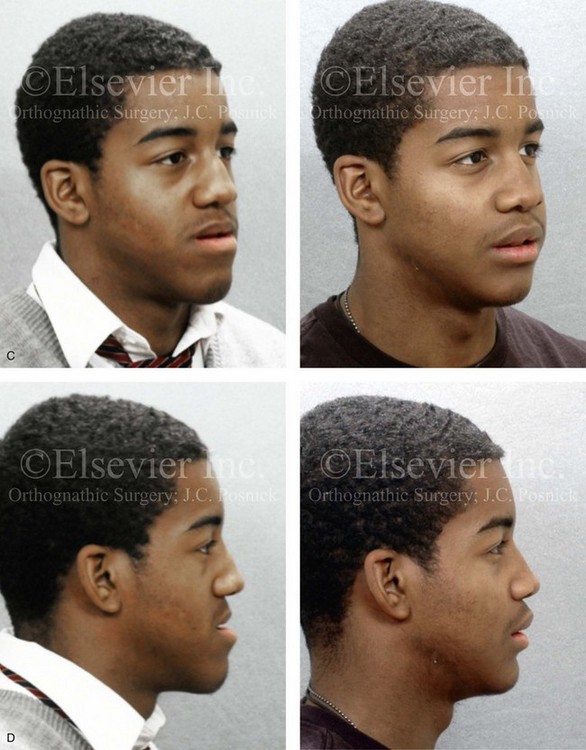

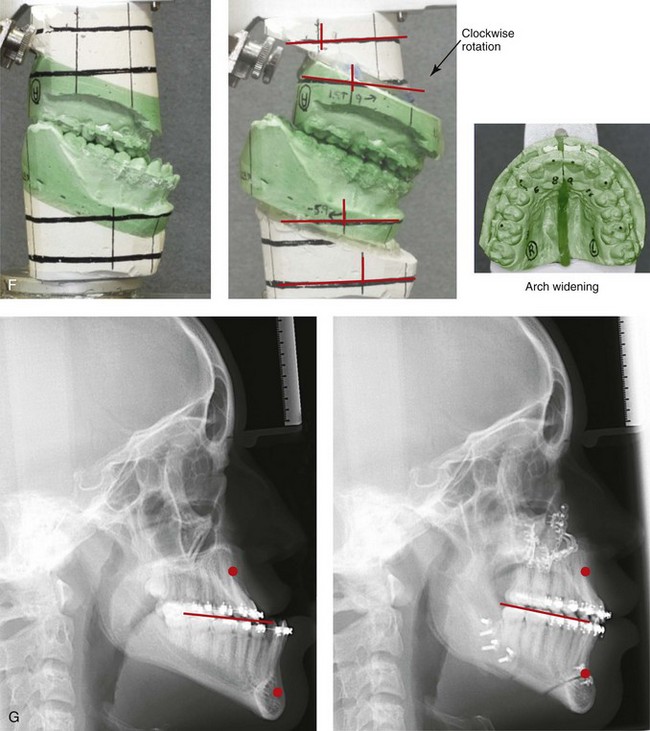

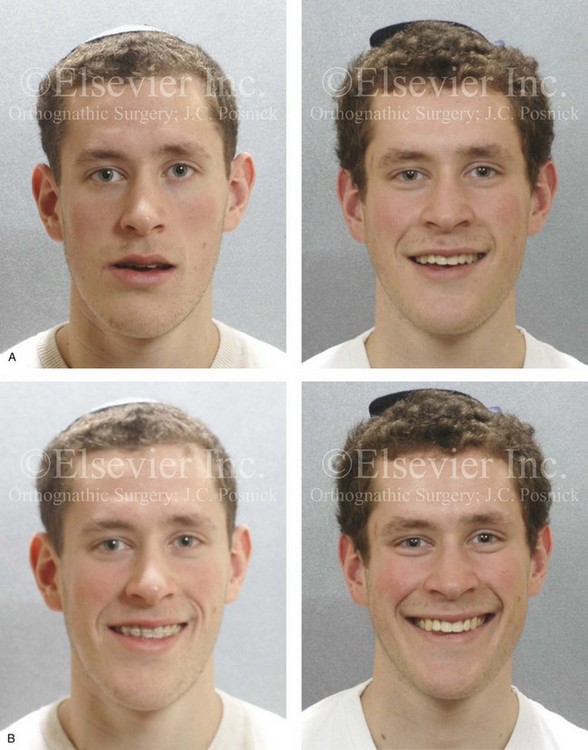

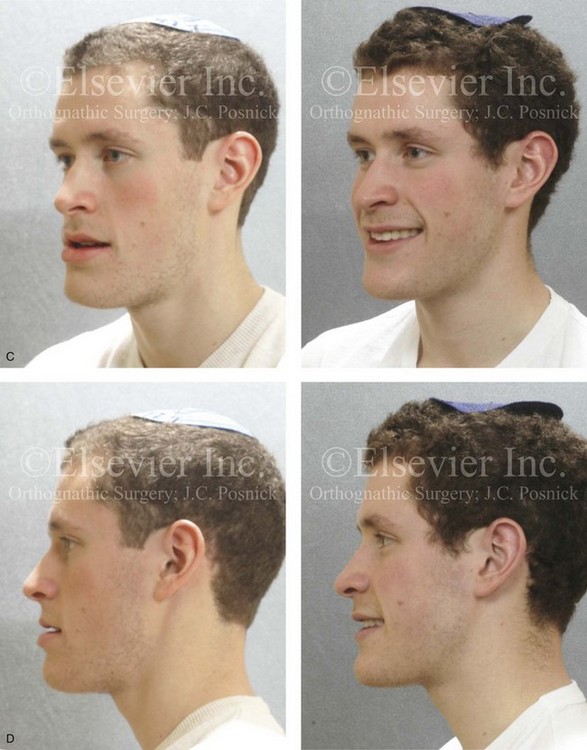

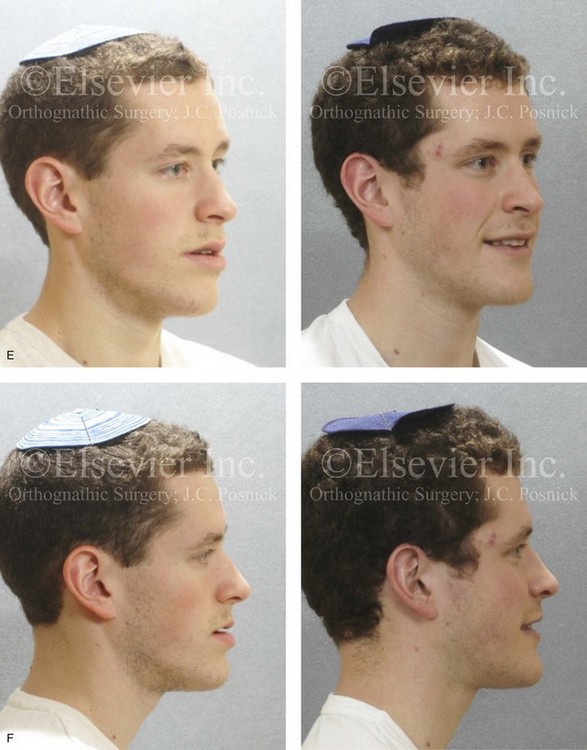

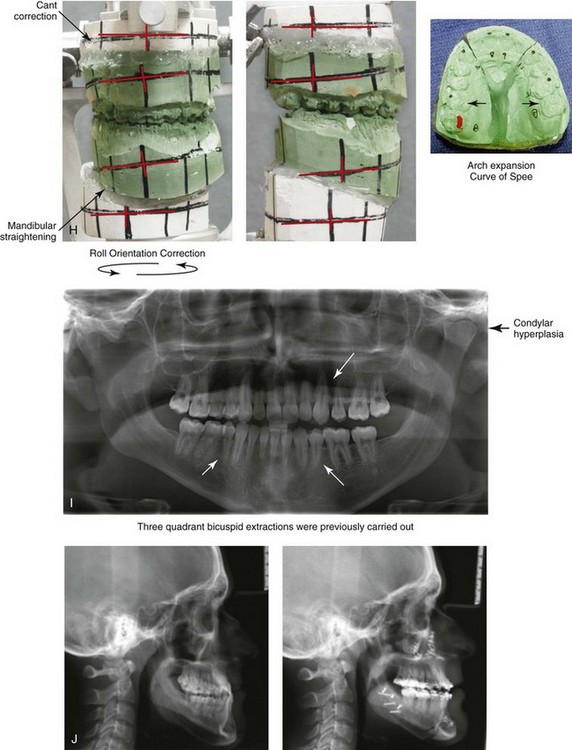

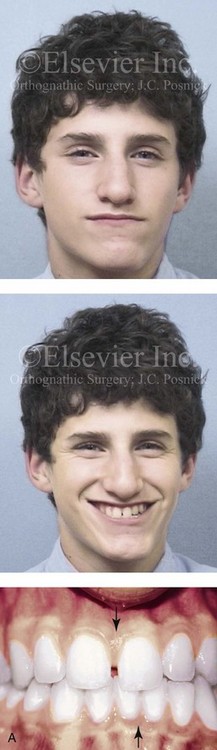

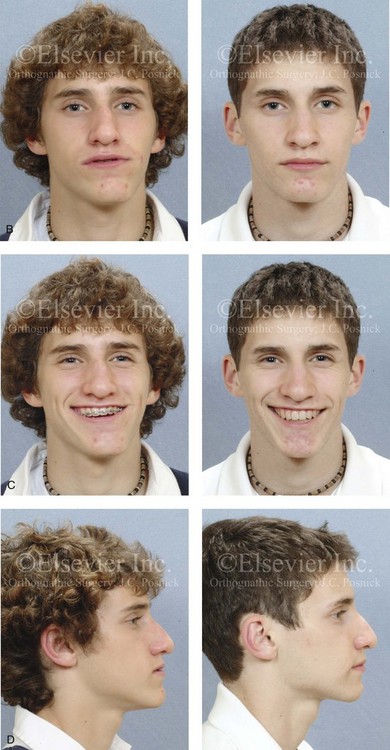

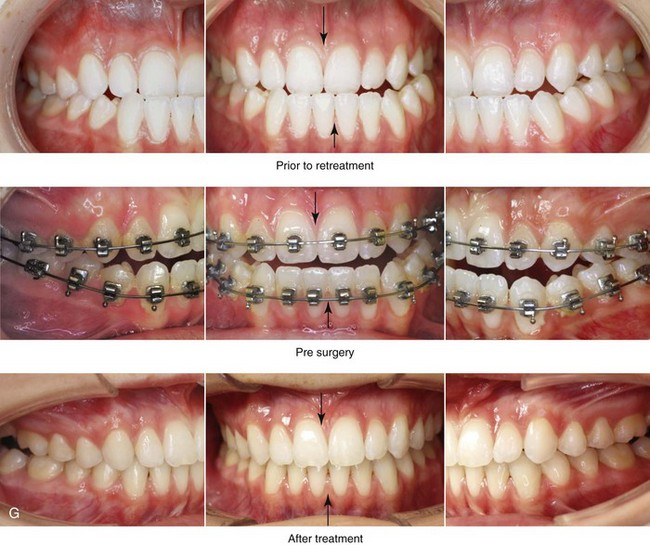

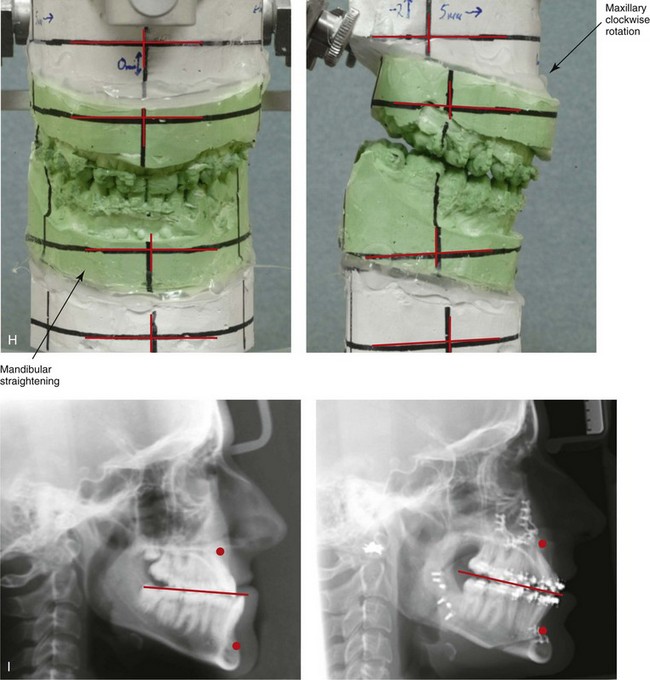

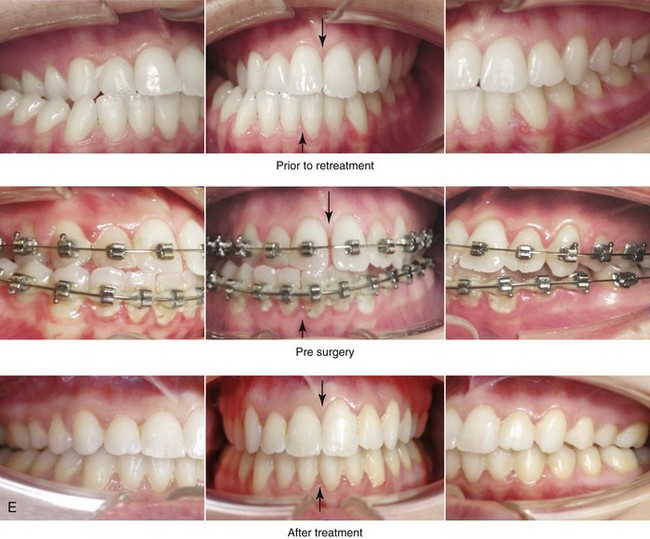

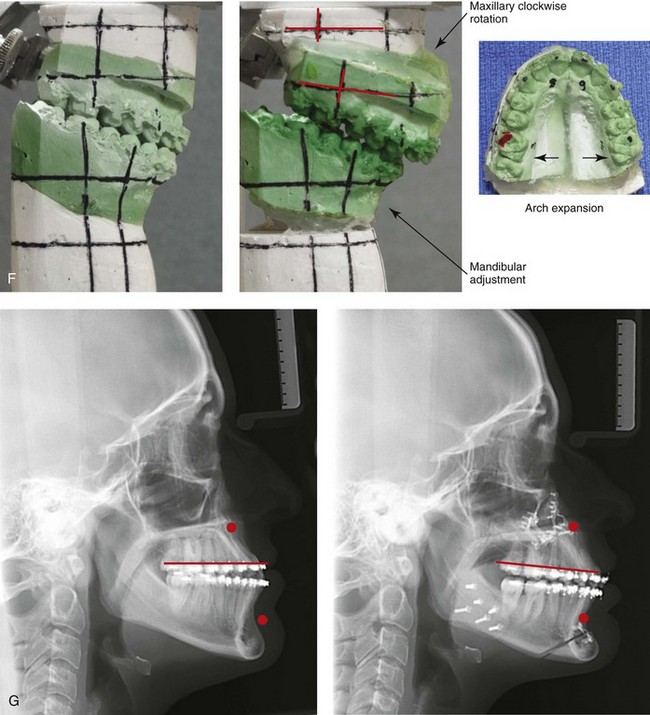

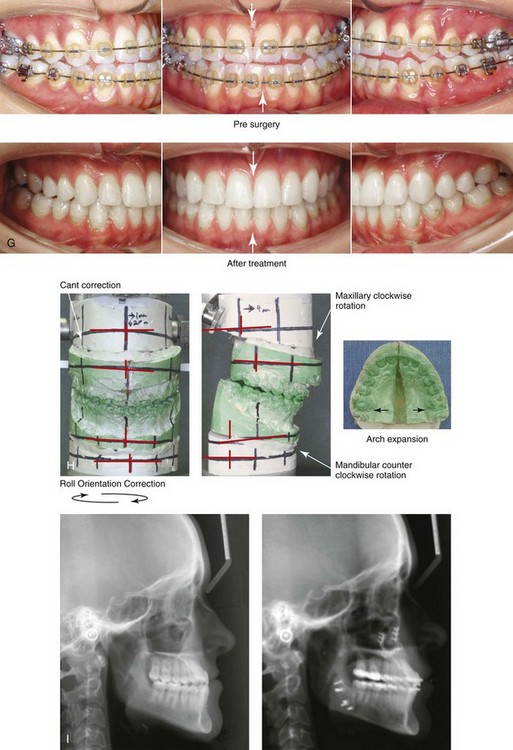

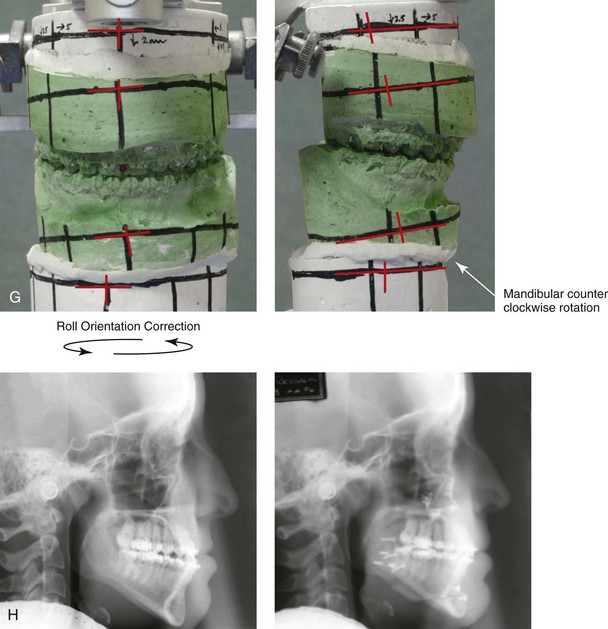

22 • Hemimandibular Hyperplasia: Type I Condylar Hyperactivity • Hemimandibular Elongation: Type II Condylar Hyperactivity • Assessing Jaw Growth Maturity • High Partial Condylectomy Procedure for Active Condylar Hyperactivity • Presurgical Orthodontic Treatment • Complications, Informed Consent, and Patient Education • Malocclusion after Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery • Temporomandibular Disorders: The Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery A specific pattern of dentofacial deformity that occurs after birth and that primarily affects the mandible may be referred to as an asymmetric mandibular excess growth anomaly.* This is a useful term for name recognition, but it falls short of explaining the causes and effects of this common pattern of jaw deformity. This condition typically results in an uneven Angle Class III malocclusion, and it has been referred to by a variety of terms, including deviated mandibular prognathism, condylar hyperplasia, mandibular lateral gnathism, osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle, and asymmetric Class III dentofacial deformity. The overall effect on maxillofacial morphology also includes the secondary deformities that occur to the maxilla, the nose, the chin region, the position of the teeth, and the distortions that are visually observed in the overlying soft-tissue envelope. These effects are dependent on multiple factors, including the intensity of the mandibular hyperactivity; the patient’s age when the abnormal bone growth begins; any underlying hereditary dentofacial deformity tendency; and the treatment that was previously rendered (i.e., orthodontic, dental, or surgical) before the patient’s arrival to the surgeon for evaluation. These asymmetric mandibular excess growth patterns may be confused with other causes of maxillomandibular asymmetry (i.e., hemifacial hyperplasia, hemifacial microsomia, growth disturbance after a condyle injury during childhood).10,27,48,49,55,93,94,124 Most misdiagnosis are easily clarified by taking an accurate history, completing a physical examination, and reviewing the patient’s radiographs (Fig. 22-1). Figure 22-1 Asymmetric mandibular excess growth patterns are often confused with other causes of maxillomandibular asymmetry. Most misdiagnoses are easily clarified by taking an accurate patient history, completing a physical examination, and reviewing the patient’s radiographs. A, A teenage girl with hemifacial hyperplasia of the right side is shown. This anomaly involves the overgrowth of both the soft and hard tissues on one side of the face. There is an asymmetric Class III malocclusion with a shift of the mandibular dental midline to the opposite side. B, Hemifacial microsomia results in the deficiency of tissues within the first and second brachial arches on one side of the face. The intraoral examination is usually consistent with an asymmetric Class II excess overjet malocclusion. This 15-year-old girl with hemifacial microsomia of the right side demonstrates these findings. There is a shift of the mandibular dental midline toward the ipsilateral side. C, A 12-year-old boy in the permanent dentition sustained a right condyle fracture of the mandible earlier during his life with resulting ipsilateral (right side) mandibular hypoplasia and secondary deformities of the maxilla. He presented with an asymmetric Class II deep-bite malocclusion. There is a shift of the mandibular dental midline toward the ipsilateral side. The overlying soft-tissue envelope is distorted but not malformed. Obwegeser believes that this dentofacial deformity is caused by two different growth regulators.23–25,68–91 The first is a more rare form, and it is clinically characterized by an increase in volume of all parts of the affected side of the mandible, without a lateral shift of the chin to the opposite side. Its primary effects end near the midline at the symphysis (Figs. 22-2 through 22-5). The second and more common form of this dentofacial deformity is characterized by an elongation of the affected side of the mandible, often with widening of the gonial angle and with clear displacement (i.e. lateral shift) of the midline of the chin and the mandibular dental midline to the opposite side of the face (Figs. 22-6 through 22-14). Figure 22-2 A teenage girl with right side hemimandibular hyperplasia. She demonstrates a typical phenotype as described within the chapter. A, Frontal facial and computed tomography (CT) scan views without intervention. B, Left facial oblique and CT scan views without intervention. C, Left profile and CT scan views without intervention. D, Right facial oblique and CT scan views without intervention. E, Right profile and CT scan views without intervention. F, Frontal and submental vertex CT scan views without intervention. Figure 22-3 A woman in her early 20s with left side hemimandibular hyperplasia. She demonstrates a typical phenotype as described within the chapter. A, Frontal facial and occlusal views without intervention. B, Facial and posteroanterior cephalometric views without intervention. C, Right profile and lateral cephalometric views without intervention. D, Asymmetry of the mandibular inferior borders is demonstrated in the left and right facial oblique views without intervention. Figure 22-4 A man in his mid 20s with an atypical hybrid form of an asymmetric mandibular excess growth pattern on the right is shown without treatment intervention. A, Frontal facial view in repose. Occlusal views are also shown. The mandibular dental midline is tipped to the right. B, Frontal facial view with smile. A posteroanterior cephalometric radiograph is also shown. C, Left facial oblique and CT scan views without intervention. D, Left profile and CT scan views without intervention. E, Right facial oblique and CT scan views without intervention. F, Right profile and CT scan views without intervention. Figure 22-5 A 17-year-old female with hemimandibular hyperplasia of the left side and the typical facial and occlusal phenotype. She also has a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing. She underwent a comprehensive orthodontic and orthognathic surgical approach. Her procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (minimal advancement, cant correction, and arch expansion); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (cant correction and minimal horizontal advancement); left mandibular inferior border recontouring; osseous genioplasty (asymmetry correction); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. Note that asymmetry is present at the inferior borders before surgery and that there is much improvement afterward. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left facial oblique views before and after reconstruction. D, Right facial oblique views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before surgery and after reconstruction. F, Articulated dental models that indicate analytic surgical planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction. Figure 22-6 This is a 15-year-old girl who had been evaluated for routine orthodontic care when she was 12½ years old. At that time, she had not yet begun her menses or undergone a pubertal growth spurt. Routine orthodontics were initiated. By the time she was 15 years old (i.e., 2 years after menarche and a pubertal growth spurt), she developed an obvious asymmetric mandibular excess growth pattern due to right condylar overgrowth (Type II Hemimandibular Elongation). This resulted in both facial asymmetry and an asymmetric Angle Class III negative overjet with a posterior crossbite malocclusion. The mandibular dental midline and chin are shifted to the contralateral side. A, Facial and occlusal views when the patient was 12 years old. B, Facial and occlusal views when the patient was 15 years old. C, Panorex radiographs when the patient was 12 and 15 years old, respectively. Figure 22-7 A 17-year-old boy with a diagnosis of left hemimandibular elongation is shown. This condition affects his chewing and speech articulation. The patient has a lifelong history of the obstruction of his nasal breathing. During his early teenage years, the patient underwent an initial phase of orthodontics, without success. He was referred for surgical evaluation and then underwent a combined redo orthodontic and surgical approach. With the relief of dental compensation, the patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, cant correction, arch expansion, and clockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (cant correction and mandibular straightening); septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction; and osseous genioplasty (straightening). A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontic decompensation, and 4 years after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment. Figure 22-8 A 17-year-old male high school student was referred by his orthodontist for surgical evaluation. His asymmetric Class III negative overjet anterior open-bite malocclusion was consistent with hemimandibular elongation. He required redo orthodontics and jaw surgery with a non-extraction approach. The patient had a lifelong history of nasal obstruction and consistent physical findings, so intranasal procedures were also required. With orthodontic decompensation complete, the patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (arch expansion, horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, and clockwise rotation); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal set-back); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after the completion of treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment. Note the improved A-point to B-point relationship that has been achieved through maxillary clockwise rotation. Figure 22-9 A 20-year-old man with left side hemimandibular elongation is shown. During his teenage years, he underwent attempted growth modification and orthodontic camouflage that included the removal of three bicuspids, without success. He had a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing. He was referred to this surgeon for evaluation and agreed to a comprehensive redo orthodontic and orthognathic approach. With the relief of dental compensation, his surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (minimal advancement, vertical adjustment, cant correction, arch expansion, and the correction of the curve of Spee); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening and asymmetric correction); osseous genioplasty (asymmetry improvement); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Left profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Right oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. F, Right profile views before and after reconstruction. G, Occlusal views before retreatment, after orthodontic decompensation, and after treatment. Note that the left mandibular second molar and the right maxillary second molar are unopposed; this is a result of the orthodontic extraction pattern. H, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. I, Panorex radiograph taken before retreatment that indicates left condyle hyperplasia and missing bicuspids in three quadrants. J, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction. Figure 22-10 A teenaged boy with right side hemimandibular elongation. When he was between 10 and 14 years old, he was treated with growth modification attempts and then orthodontic camouflage. His overjet improved at the expense of the dental compensation, and the facial deformity remained. He was referred to this surgeon, who recommended stopping active treatment until the patient was skeletally mature. When he was 17 years old, he underwent redo orthodontics and an orthognathic approach. The orthodontics were carried out without extractions, which left the maxillary incisors procumbent. Clockwise rotation of the maxillomandibular complex as part of the orthognathic correction was helpful to overcome the facial disharmony. The patient’s surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (cant correction, horizontal advancement, clockwise rotation, arch expansion, and vertical lengthening); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening and clockwise rotation); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Facial and occlusal views when the patient was 14 years old, after failed growth modification and orthodontic camouflage. B, Facial views in repose before and after reconstruction. C, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views when the patient was 14 years old just after the removal of orthodontics appliances, with retreatment in preparation for surgery, and after reconstruction. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction. Clockwise rotation of the maxillomandibular complex was helpful to improve the A-point to B-point relationship, despite maxillary incisor procumbancy. Figure 22-11 A 17-year-old girl with right side hemimandibular elongation. When she was between 10 and 14 years old, she was treated with growth modification and orthodontic camouflage techniques. She was referred to this surgeon when she was 17 years old to address her facial asymmetry and malocclusion. She underwent redo orthodontics to decompensate the arches as well as an orthognathic approach. Her surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement and clockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Left profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Right oblique views before and after reconstruction. F, Right profile views before and after reconstruction. G, Occlusal views before retreatment, in preparation for surgery, and after reconstruction. H, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. I, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction. Figure 22-12 A 25-year-old woman with left side hemimandibular elongation. She was treated with growth modification and then orthodontic camouflage earlier in life, without success. She was referred to this surgeon and underwent redo orthodontics to decompensate the arches as well as an orthognathic approach. Lifelong nasal obstruction and intranasal examination confirmed the need for septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. The orthodontics were carried out without extractions, which left the maxillary incisors procumbent. Clockwise rotation of the maxilla as part of the orthognathic correction was helpful to overcome this problem and to improve the A-point to B-point relationship. Her surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (cant correction, horizontal advancement, clockwise rotation, and arch expansion); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Facial views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, in preparation for surgery, and after reconstruction. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction. Figure 22-13 A 20-year-old woman with right side hemimandibular elongation. She was treated with orthodontic camouflage techniques, without success. She was referred to this surgeon and underwent an orthognathic and redo orthodontic approach. Her surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, clockwise rotation, and arch expansion); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (straightening and asymmetric correction); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Facial views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left oblique views before and after reconstruction. D, Left profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Right oblique views before and after reconstruction. F, Right profile views before and after reconstruction. G, Occlusal views in preparation for surgery and after reconstruction. H, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. I, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction. Clockwise rotation of the maxilla was helpful to improve the A-point to B-point relationship. Figure 22-14 A 17-year-old girl with left side hemimandibular elongation. Earlier in her life, she was treated with growth modification and orthodontic camouflage techniques, without success. She also has a lifelong history of nasal obstruction. She was referred to this surgeon and underwent redo orthodontics and an orthognathic approach. Her surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (cant correction and horizontal advancement); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening); osseous genioplasty (minimal horizontal advancement); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Facial views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Left oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Right oblique views before and after reconstruction. E, Profile views before and after reconstruction. F, Occlusal views before retreatment, in preparation for surgery, and after reconstruction. Note that the maxillary and mandible dental midlines are improved but not fully corrected. G, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. H, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction. Obwegeser also stated that these two pure forms of dentofacial deformity may present as a spectrum.23–25,68–91 He called these two pure dentofacial deformities Type I or hemimandibular hyperplasia and Type II or hemimandibular elongation. Obwegeser hypothesized that the steering mechanism for the growth of these two distinct mandibular anomalies is located entirely within the cartilaginous zone of the condylar head. This was proven to him by the fact that, whenever a very rapidly developing mandibular overgrowth (either Type I or Type II) was encountered, he was able to arrest the growth and prevent further deformity by completing a high condylar resection. Raijmakers and colleagues carried out a meta-analysis to determine gender differences when it came to the diagnosis of asymmetric mandibular excess.101 Ten studies were reviewed, and these included a total of 275 affected patients. The meta-analysis showed a clear predominance of female patients in the study populations. The male and female patients had an equal distribution of left- and right-sided condylar overgrowth. The authors postulate that hormonal variations—especially of estrogen in women—may explain these differences. An alternative explanation put forth for this apparent female predilection is a difference in motivation between the sexes to seek the correction of their facial asymmetry (see Fig. 22-6). Slootweg and Muller described four histologically different types of mandibular condylar hyperplasia.116 They proposed a classification system that is based on histologic criteria, and they divided hyperplastic condyles into four types, depending on the arrangement and morphology of the various layers of the condyle. These condylar layers were the fibrous articular layer; the undifferentiated mesenchyme proliferative layer; the transitional layer; and the hypertrophic cartilage layer. Villanueva-Alcojol and colleagues attempted to correlate demographic and clinical presentations of condylar hyperplasia with the described histopathologic features and then with the associated scintigraphic and clinical findings after treatment with high condylectomy during the active phase.122 Interestingly, the authors were unable to find a correlation between the histologic type (as described by Slootweg and Muller116) and the uptake of the affected condyle on bone single photon emission computed tomography or between the patient’s age and his or her histologic type. The preferred treatment to correct the dysmorphology for all forms of condylar hyperplasia is surgical including the repositioning and recontouring of the bones in combination with orthodontics to align the teeth.* The extent of treatment depends on the presenting dysmorphology and the status of condylar growth. If ongoing condylar growth is documented, then a form of high condylectomy should be considered to arrest progressive dysmorphology.20,21,40,42

Asymmetric Mandibular Excess Growth Patterns

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree