Introduction

In 1984, Song and colleagues introduced the anterolateral thigh flap based on septocutaneous branches of the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery. Since that time, the anterolateral thigh flap has gained popularity for use as a soft tissue flap for reconstruction of regional as well as distant defects. This flap can provide muscle, fascia, skin, or any of these in combination. Early anatomic dissections on cadavers noted that the vascular anatomy was variable and that the majority of skin vessels were septocutaneous compared with musculocutaneous in nature. More recent studies and series indicate the skin vessels are predominantly musculocutaneous perforators and less commonly septocutaneous vessels. In 1991, Zhou et al. evaluated their results of utilizing this flap for the reconstruction of defects in various regions of the body. In 1993, Koshima and colleagues reported on 22 cases of head and neck reconstruction utilizing this flap. This flap has been extensively reported in the literature and has become a workhorse flap for reconstruction of small or large defects, both simple and complex, with excellent results and minimal morbidity at the donor site.

Anterolateral Thigh Flap

The anterolateral thigh flap is relatively easy to harvest once the technique of perforator flap dissection has been learned. The ALT has a reliable blood supply despite some anatomic variability, it can provide a long pedicle with large-diameter vessels, and it is pliable and can be thinned to a significant degree without compromising blood supply. It can also be used as a flow-through flap, and, because of its unique position, allows for a two-team approach to the reconstruction of most defects in the body. The flap can also provide different tissue components such as muscle, fascia, and skin in a variety of combinations. The anterolateral thigh flap does have disadvantages such as a color mismatch when reconstructing facial defects, and the presence of hair in some patients. When large defects are reconstructed, skin grafts are required at the donor site. In rare instances, there is a lack of vessels with a reasonable size. The anteromedial thigh (AMT) flap has similar advantages and disadvantages to the ALT flap. The harvest of the AMT flap is simple and many of the same properties of tissues that can be included are similar. This flap is usually used when the anterolateral thigh flap vessels are inadequate or cannot be found.

Flap Anatomy (see Figs 59.1 , Fig 13.1 , Fig 13.2 , Fig 13.4 , Fig 13.19 )

Arterial Supply of the Flap ( Figs 59.1 , 13.1 , 13.2 and 13.4 )

The anterolateral thigh flap is supplied by either septocutaneous vessels or musculocutaneous perforators that usually arise from the descending branch of the LCFA. The flap is primarily based on musculocutaneous perforators vs septocutaneous ones (87% vs 13%). Less commonly, the perforators may originate from other sources such as the transverse branch of the LCFA.

Dominant:

branches of the descending branch of the LCFA

Length: 12 cm (range 8–16 cm)

Diameter: 2.1 mm (range 2–2.5 mm)

The descending branch of the LCFA courses obliquely along the intermuscular septum between the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis muscles. It exits in the majority of cases within a circle of 3 cm radius located at the midpoint of a line drawn between the anterior superior iliac spine and the superior lateral border of the patella as either a septocutaneous vessel or a musculocutaneous perforator, or both. Septocutaneous vessels run between the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis and traverse the fascia to supply the skin of the anterolateral thigh. At the exit point, musculocutaneous perforators traverse through the vastus lateralis muscle, giving off numerous intramuscular branches before piercing through the fascia and supplying the skin. In 30% of cases, the descending branch will divide into a medial and lateral branch, with the latter giving rise to the skin vessels.

In 2% of cases there may be an absence of any skin vessels, either septocutaneous or musculocutaneous, or the perforator may be too small in diameter, necessitating exploration more proximally to determine if perforators are originating from the transverse branch of the LCFA or if use of an alternative free flap is required. The artery may also course without the venae comitantes along its side and turn back at a more proximal point to join the course of the vein.

Minor:

perforator of transverse branch of LCFA

Length: 11 cm (range 9–13 cm)

Diameter: 2.1 mm (range 1.5–2.5 mm)

Less commonly, the septocutaneous vessel or musculocutaneous perforator arises from the transverse branch of the LCFA and runs parallel with the vastus lateralis muscle.

Venous Drainage of the Flap

Primary:

venae comitantes of the lateral circumflex femoral vessel and its branches

Length: 12 cm (range 8–16 cm)

Diameter: 2.3 mm (range 1.8–3.3 mm)

Two venae comitantes accompany the arterial pedicle of the anterolateral thigh flap. In rare instances, there may be no existing veins with the perforator pedicle.

Flap Innervation ( Figs 13.2 and 13.19 )

Sensory:

The anterolateral thigh flap may be harvested as a sensate flap by including the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve proximally with the flap and anastomosing it to a sensory nerve at the recipient site. The sensory nerve branches pierce the muscle fascia 10 cm below the inguinal ligament medial to the tensor fascia lata muscle. The nerve in that area splits into anterior and posterior branches to innervate the anterolateral aspect of the thigh (see Fig. 13.19 ).

Motor:

The vastus lateral is innervated by a branch of the posterior division of the femoral nerve. This branch accompanies the descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery. This nerve can be included with flap harvest and anastomosed to a motor nerve at the recipient site for a functional reconstruction (see Fig. 13.2 ).

Flap Components

The anterolateral thigh flap can be harvested as a cutaneous flap consisting of skin and subcutaneous tissue based on either a septocutaneous vessel or musculocutaneous perforator. It may also be elevated as a composite flap, consisting of a fascial (fasciocutaneous anterolateral thigh flap) or muscular (vastus lateralis myocutaneous anterolateral thigh flap) component. Furthermore, the flap can be harvested as a combined flap to include various other tissues (including rectus femoris muscle, tensor fascia lata, anteromedial thigh skin or vastus lateralis on a separate perforator) based on blood supply from the descending branch or any other branches of the lateral femoral circumflex system. These chimeric flaps consist of multiple tissue combinations, each with an independent vascular supply. For example, a fasciocutaneous anterolateral thigh flap based on a musculocutaneous perforator may be harvested with the rectus femoris muscle that is based on an independent pedicle from the lateral circumflex femoral system and would be termed a chimeric fasciocutaneous anterolateral thigh myocutaneous perforator and rectus femoris muscle flap.

Advantages

- •

Ease of harvest with relatively constant anatomy

- •

Long length and large pedicle

- •

Versatility in design with variable thickness and incorporation of various tissue components

- •

Ability to provide sensory innervation

- •

Lack of significant donor site morbidity

- •

Decreased operative time with two-team approach.

Disadvantages

- •

Color mismatch in some patients for facial reconstruction

- •

Presence of hair in some male patients

- •

Skin graft requirement at donor site if >8 cm or 9 cm width of harvested tissue.

- •

Lack of vessels with reasonable size in rare cases.

Preoperative Preparation

Preoperative preparation includes functional evaluation of knee extension as the vastus lateralis muscle is a large component of quadriceps function. Patients with impairment in knee extension or with knee instability may have increased functional deficit after anterolateral thigh flap harvest and intramuscular dissection of the vastus lateralis. It is also important to note any previous scars that may affect flap design. Prior skin graft donor sites can be incorporated as part of the flap and would be visible as such at the recipient site.

The thickness of the thigh tissue should be assessed preoperatively. In obese patients, the flap may be very thick and may require primary thinning as well as subsequent debulking procedures in order to achieve a reasonable outcome. Male patients with thick hair may require laser hair removal or may need to shave the hair for certain types of reconstruction. Another option is to select a different donor site which is non-hair bearing. Flaps with hair are not ideal for reconstructions such as intraoral lining defects.

Patients with significant atherosclerotic disease affecting the arterial vasculature require preoperative evaluation using angiography. Previous injury or operations to the upper thigh require a work-up that will carefully assess the condition of the leg soft tissues and vasculature supplying the region of the proposed flap.

Flap Design

Anatomic Landmarks ( Fig. 59.2 )

Markings for the anterolateral thigh flap are based on the location of the skin vessels that supply the skin territory of the flap. Important landmarks for the flap include the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the superior lateral border of the patella. Taking into account that the perforators are located either at this line connection, the ASIS to the lateral patella (septocutaneous perforators), or posterior to this line (musculocutaneous perforators), the skin paddle is designed either centered over this line or the design can be shifted slightly posterior. A circle of 3 cm radius defines the area at which the skin vessels, either septocutaneous vessels or musculocutaneous perforators, exit. The skin vessels are often found in the inferior lateral quadrant of the circle. The most accurate method to design the flap is to mark the landmarks mentioned, Doppler the skin vessels, and design the flap based on the Dopplered skin vessels. The medial incision is made first, the perforators are found, and the flap is remarked.

General Thoughts About Flap Design

Although a large skin paddle up to 35 cm long and 25 cm wide can be harvested on a single dominant perforator, when possible, incorporation of two or more perforators will ensure greater success.

Limiting the width of the flap to 7–9 cm allows for primary closure of the donor site without the need for a skin graft.

It is not necessary to design the flap with the skin vessel at the center. An eccentric flap with the skin vessel entering at the proximal portion of the flap will allow for greater pedicle length. If the flap is to be pedicled in a reverse fashion for knee reconstruction, the skin island can be designed so that the skin perpetrator is at the distal end of the skin paddle. This will allow for further distal reach.

Aside from the variability in flap dimensions, the versatility of the anterolateral thigh flap in terms of tissue construct allows it to be tailored to the needs of the recipient site. In areas requiring a relatively thin flap, such as the foot and ankle, the anterolateral thigh flap can be elevated as a cutaneous flap as thin as 5 mm in thickness.

When extensive soft tissue coverage is needed, and muscle is believed to be necessary, the anterolateral thigh flap can be harvested with vastus lateralis muscle as a myocutaneous flap or rectus femoris muscle as a chimeric flap. Moreover, in recipient sites with a composite 3-dimensional defect, the anterolateral thigh flap can be designed with other tissue components based on separate perforators to more adequately cover the defect.

Sensate flaps can be constructed by including the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve in the proximal portion of the flap.

Special Considerations

Head and Neck Reconstruction

The anterolateral thigh flap can be harvested as a thin cutaneous perforator flap for defects that need minimal tissue bulk for coverage, as in tongue reconstruction. This can be done either by performing a suprafascial dissection or by thinning the flap after elevation. The flap may also be harvested with multiple skin islands, as needed in simultaneous reconstruction of oral lining and cheek skin, by potentially dividing the flap into two skin paddles based on separate perforators or de-epithelializing the flap to create two separate skin islands based on a single perforator.

Application of the anterolateral thigh flap for cervical or thoracic esophageal reconstruction has also been performed by tubing the flap at the donor site, then transferring to the defect for reconstruction. This can be performed in two operations to assure suture line healing after tubing the flap and prior to transfer. However, this is only indicated if the defect has not been created. In most cases, surgeons will tube the flap at the donor site and transfer in the same setting.

For pharyngoesophageal reconstruction, a flap is designed with a width of approximately 9 cm, to achieve a 3 cm diameter tube. A separate skin paddle based on a separate perforator can be used for monitoring of the flap. This is no longer commonly performed, as the flap can now be monitored using an implantable Doppler.

Abdominal Wall Reconstruction

Flap design for abdominal wall reconstruction is based on the size and location of the defect and the need for a fascial component at the recipient site. For lower abdominal wall and perineal defects, a pedicled fasciocutaneous anterolateral thigh flap with or without incorporation of the iliotibial tract or vastus lateralis muscle can be harvested with the pedicle pivot point approximately 7–10 cm below the ASIS, correlating with the origin of the lateral circumflex femoral artery. For large defects encompassing both the upper and lower abdomen, a free myocutaneous anterolateral thigh flap with a cuff of vastus lateralis along with the iliotibial tract or tensor fascia lata flap provides an effective reconstruction.

Upper Extremity Reconstruction

Most upper extremity defects require a relatively thin flap for coverage. A cutaneous anterolateral thigh flap can be harvested and trimmed to as little as 5 mm thickness to facilitate tendon coverage and filling of soft tissue defects. Alternatively, the anterolateral thigh flap can be elevated as an adipofascial flap for areas with adequate skin but lack of soft tissue.

Lower Extremity Reconstruction

Application for lower extremity reconstruction is based on the general flap design with variation in tissue construct tailored to the recipient site requirement. Certain areas such as the foot and ankle will require thin cutaneous flaps, while other areas will require more tissue bulk. In cases of trauma with vascular compromise, an anterolateral thigh flap can be designed as a flow-through flap to preserve the arterial vasculature at the recipient site. For defects closer in proximity such as the groin or knee, a pedicled flap can be elevated with the pedicle based proximally or distally, respectively. A distal pedicled flap is based on retrograde blood flow of the descending branch of the LCFA with the pivot point 3–10 cm above the knee. Longer pedicle length can be achieved by designing the flap more proximally on the upper thigh.

Breast Reconstruction

The anterolateral thigh flap may be used as an alternative tissue flap for breast reconstruction by creation of a fasciocutaneous flap with a small skin island and large underlying fat pad. Subdermal undermining posterior to the medial flap incision allows for the incorporation of a fat pad ranging in size from 10 × 12 cm to 14 × 22 cm. The donor site for this type of reconstruction is unfavorable.

Differences in Design, if Any, When Performing the Flap as Pedicled or Free

Although more commonly used as a free flap, the anterolateral thigh flap can be harvested and transferred as a pedicled flap to cover tissue defects in the groin, lower abdomen, perineum, and knee. The pedicled anterolateral thigh flap is elevated in the same manner as its free counterpart and with the same septocutaneous or musculocutaneous pedicle based on the descending branch of the LCFA. Flap boundaries are based on recipient defect requirements and can be designed eccentrically about a chosen skin vessel to obtain more length. The most proximal pivot point for a proximal pedicled flap is 7–10 cm below the ASIS and the pivot point for a distally-based pedicled flap ranges from 3 cm to 10 cm above the knee. For local thigh defects requiring minor rotation, a proximal pedicled flap need not be designed as an island flap and can instead, preserve a proximal skin pedicle to insure better venous outflow.

Flap Dimensions

Skin Island Dimensions

Length: 21 cm (range 4–35 cm)

Maximum to close primarily: 22 cm

Width: 8 cm (range 4–25 cm)

Maximum to close primarily: 8–9 cm (at the center of the thigh)

Thickness: 5 mm (range 3–20 mm)

These dimensions are highly dependent on the patient’s body habitus and the skin tone and quality. The thickness of the flap is variable and primary and/or secondary thinning can be performed to achieve a thinness of 5 mm. Primary closure is more difficult in the proximal and distal aspect of the thigh.

Muscle Dimensions

Length: from 2 cm (cuff) to 20 cm (entire muscle)

The descending branch of the LCFA passes through the vastus lateralis muscle and a segment of muscle can be harvested based on one or more branches. Therefore, the size and location of the segment of muscle are variable and an extremely small segment or the entire muscle may be harvested with the flap. The tensor fascia lata muscle can be included if the ascending branch of the LCFA is included with the flap. The rectus femoris muscle or a portion of it can be harvested based on the branch from the descending branch of the LCFA.

Flap Markings

A line is marked connecting the ASIS with the lateral patella. The flap is marked over the Dopplered perforators. When a large flap is harvested, the medial incision is made, the flap is elevated in the subfascial or suprafascial plane until sizable perforators are located. The search for perforators is performed in a free style manner, which allows the surgeon to have the freedom to change the plan if anatomic variations are met ( Figs 59.2 , 59.3 ).

Patient Positioning

Generally, the patient is positioned supine on the operating table to allow for a two-team approach for flap harvest and recipient site preparation. If necessary because of the location of the defect, the flap can be harvested in the lateral or sloppy lateral position.

Anesthetic Considerations

General anesthesia with muscle relaxation is preferred for flap harvest. For certain reconstructions, regional anesthesia such as spinal block may be used.

Technique of Flap Harvest ( Figs 59.4–59.8 )

The patient is placed in the supine position and the leg is circumferentially prepared. A line is drawn extending from the anterior superior iliac spine to the lateral superior aspect of the patella. At the midpoint of this line a circle with a radius of 3 cm is drawn, delineating the predominant location of the skin vessels. Most skin vessels can usually be found in the inferior, lateral quadrant of this circle. A Doppler probe is used to establish the skin vessels within the circle. Additional skin vessels are located by Doppler probe caudad and cephalad over or slightly posterior to the intermuscular septum between the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis muscles (this septum can be palpated in thin patients as a groove between these muscles). Flap dimensions are marked based on the size of the recipient defect. In general, a flap of 8 cm or 9 cm by 22 cm is harvested with one to three skin vessels. Although experience with the anterolateral thigh flap has proven the reliability of a large skin paddle (up to 35 cm in length × 25 cm in width) based on one dominant perforator, when a large skin flap is to be harvested, the preference is to include more than one perforator. Longitudinal design of the flap allows for better donor site closure. In cases when more than one skin vessel is located intraoperatively, the surgeon has a choice of:

- •

The largest perforator that takes the shortest intramuscular course

- •

All the identified skin vessels (this may add a significant amount of time to flap harvest)

- •

More than one skin vessel and subsequently splitting the flap to fit into a geometrically favorable contour while allowing for primary closure of the donor site.

The skin vessel does not need to be located in the center of the flap. If a longer pedicle is required, the flap can be designed with the skin vessel in an eccentric position. The final design of the flap can be modified after visualizing and assessing the size and quality of the skin vessels intraoperatively.

The anterolateral thigh flap can be harvested in either a subfascial or suprafascial plane, depending on the recipient site requirements and on the amount of morbidity that is acceptable at the donor site for that individual patient. For thin flaps and when preservation of sensory innervation to parts of the thigh is required, a suprafascial dissection is preferred ( Fig. 59.4 ). Otherwise, a subfascial dissection is usually undertaken. The subfascial approach allows for easier identification of skin vessels and for better exposure of the intermuscular septum and descending branch of the LCFA, thereby providing the surgeon with a general map of the vascular anatomy of the area before beginning the skin vessel and pedicle dissection.

Loupe magnification during dissection is recommended as it aids in locating the skin vessels, avoids unnecessary injury to the pedicle, and helps to clearly visualize branches of the vessels. A lower magnification microscope is useful when dissecting very small perforators in children and adults.

Suprafascial Dissection ( Figs 59.3 , 59.4 )

The medial margin of the flap incision is first made through the skin and subcutaneous tissue, down to the level of the fascia of the thigh. Dissection proceeds above the fascia in a lateral direction using tenotomy scissors until the previously Dopplered skin vessels are reached. Strict hemostasis allows for less blood staining of the surrounding tissues and easier visualization of the skin vessels. Cutaneous nerves overlying the fascia are preserved at the donor site whenever possible. After identifying a suitable skin vessel and confirming its course piercing through the fascia and entering the subcutaneous tissue, the lateral skin flap incision is made down to the same suprafascial plane and dissection proceeds in a medial direction until the same skin vessel is visualized. A fascial incision is made in the direction of the skin vessel (usually caudad) and the vessel is traced in a retrograde fashion until adequate vessel length and caliber are achieved. Inclusion of a cuff of fascia can avoid damage and twisting of the skin vessel. Dissection then proceeds in a retrograde fashion with all small branches carefully ligated or cauterized. Minimal and gentle manipulation of the skin vessel avoids vessel spasm. Traction on the pedicle is always avoided, keeping in mind that traction can occur due to the weight of the flap itself.

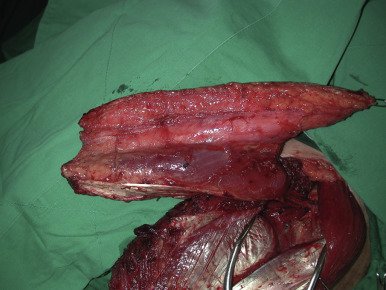

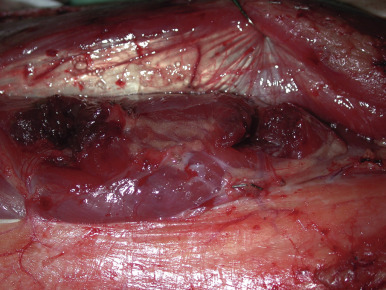

Subfascial Dissection ( Figs 59.5, 59.6, 59.7, 59.8 )

The medial incision is made down to and through the thigh fascia, exposing the rectus femoris muscle. The epimysium of this muscle is preserved and the dissection proceeds in a lateral direction until the septum separating the rectus femoris from the vastus lateralis is visualized ( Fig. 59.5 ). The entire septum is exposed by retracting the rectus femoris medially. At the medial aspect, the descending branch of the LCFA can be seen coursing over the vastus lateralis muscle ( Fig. 59.6 ). This exposure provides the operator with a map of the vascular anatomy of the region. Branches of the descending branch are observed either perforating the vastus lateralis muscle or traveling within the septum to reach the skin of the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. For septocutaneous vessels, the dissection is performed in a retrograde fashion and the vessel is dissected away from the surrounding tissues. If the skin vessel is a musculocutaneous perforator, then intramuscular dissection is performed in the following manner: the point of exit of the perforator is exposed and the muscle fibers anterior to the vessel are “lifted up” using teeth forceps; the tenotomy scissors are used to spread in a transverse plane over the perforator, and the muscle fibers are cut ( Fig. 59.7 ). This same series of steps is performed throughout the intramuscular course in a retrograde fashion. Small intramuscular branches, which generally arise from the lateral and posterior sides of the perforator and less commonly from the anterior side, are ligated. Perforator dissection proceeds until its take-off from the descending branch of the LCFA or further until adequate pedicle length is achieved ( Fig. 59.8 ). The main nerve and nerve branches supplying the vastus lateralis and the rectus femoris are carefully dissected away from the vessels and preserved.

Flap Modification/Flap Handling

Thin Flap

Thin flaps (see Ch. 26 ) may be suitable for a variety of locations throughout the body, including defects of the face and neck, axilla and forearm, anterior tibia and ankle, and dorsum of the foot and hand, as well as de-epithelialized flaps for soft tissue augmentation. Thinned flaps have the advantage of regaining quicker and better sensory innervation without nerve coaptation.

Flap thinning can be performed after flap elevation and before transection of the vascular pedicle. The pedicle entrance into the skin is marked. Preservation of at least a 2 cm radius of tissue around the pedicle is recommended to ensure adequate perfusion of the flap. The flap is thinned, beginning with the deep fat tissue (wide and flat fat lobules) and progressing up to the junction with the more superficial fat (small and round fat lobules). Usually, the quality of fat at these two levels is different, with a thin fascia present between them. Noting this characteristic of the fat lobules results in uniform defatting. Defatting before vessel ligation allows for continuous monitoring of flap perfusion throughout the defatting process and for coagulation of bleeding points when necessary. The flap can be thinned up to the dermal plexus without compromise to the blood supply, provided that the flap is within 9 cm around the perforator. A more conservative approach towards flap thinning in the primary procedure is recommended until enough experience is accumulated, as defatting can be performed easily and safely as a secondary procedure.

When Bulk is Required

The anterolateral thigh skin flap can be harvested larger than the recipient site dimensional requirement and partially de-epithelialized to add bulk ( Fig. 59.17 ). A part or all of the vastus lateralis or rectus femoris muscle, the tensor fascia lata or other skin flaps in the thigh can be harvested along with the anterolateral thigh flap as a chimeric flap to add bulk or muscle tissue to fill a defect ( Fig. 59.9 ). By inclusion of thigh fat, the anterolateral thigh flap can be used for breast reconstruction and tailored to create a volume that can match a medium-sized contralateral breast ( Fig. 59.10 ).