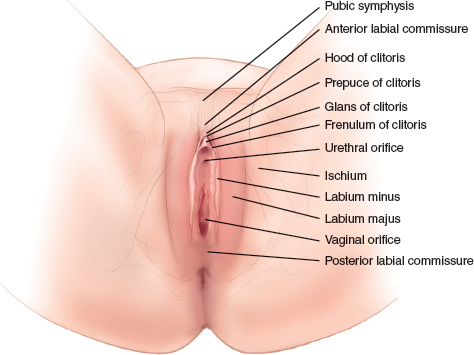

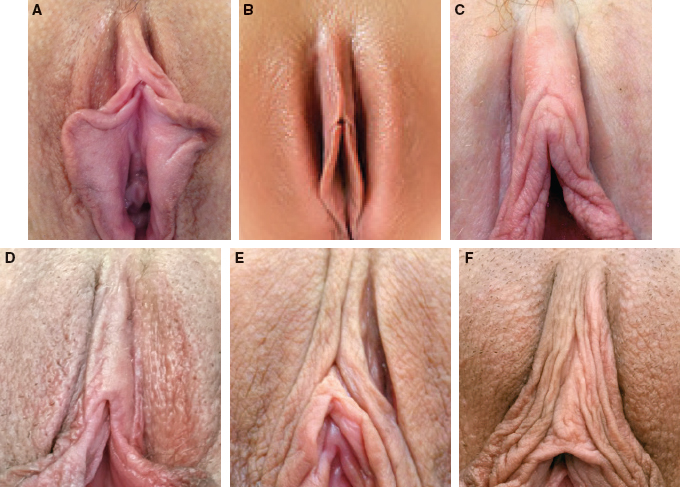

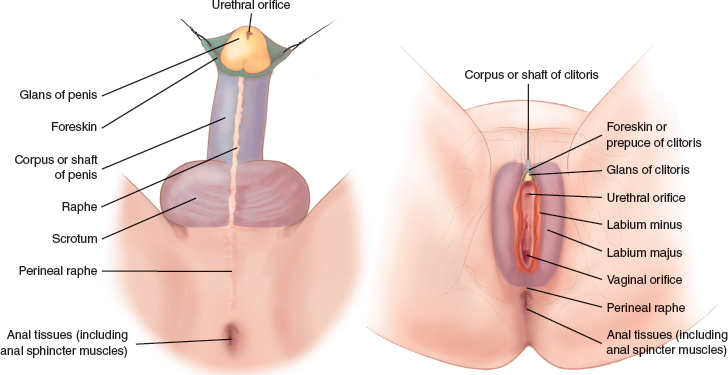

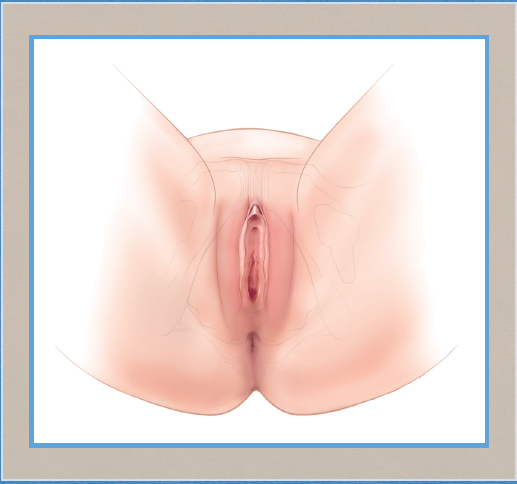

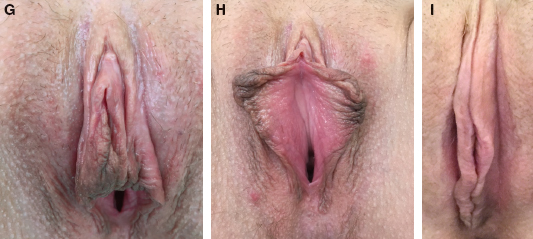

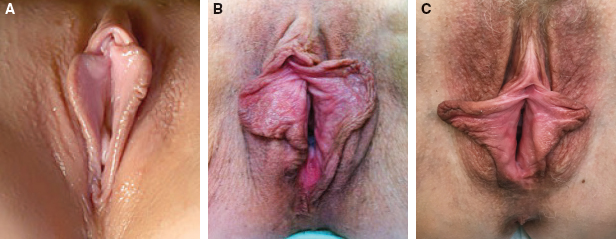

CHAPTER 1 • Understanding the anatomy of the female genitalia is fundamental to surgical planning and technique in cosmetic surgery of this area. • Systematic examination of the mons, labia majora, clitoris, and labia minora (vulval complex) is essential. • Wide variations exist in the anatomy of the vulval complex. • Hodgkinson and Hait’s aesthetic ideal of small labia minora not protruding beyond the labia minora are a desired goal of most patients.1 • In parallel with facial aesthetics and facial harmony, surgeons should consider the concept of genital harmony. • Newly documented insights into the vascular anatomy of this area may influence choice of technique. • The Motakef classification2 describes the degree of labia minora protrusion beyond the labia majora. • The Banwell classification3 describes variations in the shape and morphology of the labial anatomy that have not been previously documented. • The clitoral hood–labia minora complex in particular varies widely in appearance and is potentially a problematic area for surgeons. • Careful documentation of the size and shape of the labia and the labialclitoral complex (according to Motakef and Banwell) is critical. As the popularity of female genital surgery in our practices rises, we have seen a parallel increase in published clinical experience, available operative techniques, and mounting data in the scientific literature espousing the physical and non-physical benefits of such procedures. As shall be explored further in this book, we now have strong evidence for high patient satisfaction, minimal complication rates, and excellent safety profiles, as well as published evidence on the psychological benefits. However, to date there have been few attempts to classify the female external genitalia, a paucity of information on common anatomic variants, and little exploration or re-evaluation of the anatomy in relation to operative techniques, surgical planning, and treatment outcomes. The anatomy of the external female genitalia has been well described4 (Fig. 1-1). It consists of the mons pubis superiorly (venus mont), the clitoris with its overlying clitoral hood, the labia majora, and the labia minora. Collectively, most anatomic texts refer to this as the vulval complex. However, much of the variation in the anatomic arrangement has not been previously recognized or described; awareness and understanding of these variations may be particularly pertinent to surgical planning.5 The mons pubis is a triangular adipose tissue elevation situated anterior to the pubic symphysis (Fig. 1-2). This adipose tissue can increase during puberty or with weight gain, but it also lessens with significant weight loss and after menopause. The mons pubis is anatomically covered by pubic hair, which also decreases with age during the perimenopausal period. The prominence of the mons area can vary enormously not only because of increased fat deposition but also because of the angle of the pubic rami; both are reasons for presentation for surgical reduction of this area. Fig. 1-2 The relationship between a youthful mons and the pubic rami. The labia majora (outer lips) are two cutaneous folds that extend posteriorly from the mons pubis toward the perineal region (Fig. 1-3). They have a hair-bearing outer (lateral) aspect and an inner aspect that lacks hair. Each labia majora is filled with subcutaneous fibrofatty tissue to varying degrees but can vary from “full” and “tight” to “lax” and “baggy,” as patients often describe (Fig. 1-4). Our common practice, however, is to document a lax and baggy appearance as “empty” or “redundant” tissues. Fig. 1-3 Youthful labia majora. Fig. 1-4 Empty labia majora, commonly described by patients as “baggy.” The skin is redundant and empty. This patient presented for labia majora reduction and revision surgery of the labia minora. The original procedure was performed elsewhere. Enveloped (to varying degrees) and medial to the labia majora are the clitoris and clitoral hood and the labia minora. The labia majora are usually separated from the labia minora by a deep sulcus; this is typically well-defined and a useful surgical boundary between non-hair-bearing and hair-bearing skin (Fig. 1-5). Rarely, the deep, subcutaneous vertical attachments of this sulcus are tenuous or even absent, leading to a less-defined continuum between the labia majora and minora. In such cases, if a labia majora reduction is considered, then the scar may potentially become more visible, and this should be discussed in detail with the patient preoperatively. Fig. 1-5 A, This patient was referred for labia majora reduction and revision of the labia minora surgery performed previously by a colleague. The tissue pigmentation is not uncommon. B, Hair-bearing skin and non-hair-bearing skin. The dotted line represents the labia majora sulcus and the boundary between hair-bearing and non-hair-bearing skin. This is a useful surgical landmark for the medial marking for labia majora reduction (see Chapter 6: Labia Majora Reduction Surgery: Majoraplasty). The clitoris (clitoral body) superiorly is located under a clitoral hood (prepuce) that splits into a frenulum on either side of the introitus (vaginal vault) (Fig. 1-6). According to classic anatomic texts, the frenulum attaches most commonly to the outer aspect of the upper third of the labia minora (Fig. 1-6, A), but as seen throughout this book and as explored in more detail later in the chapter, this arrangement varies widely. The clitoral body itself can also vary significantly in size, and usually a larger clitoral body is associated with heavier clitoral hood skin. A second fold of skin may be present lateral to the clitoral hood, which either fuses with the labia minora (Fig. 1-6, G and H) or remains dominant and in continuity with the labia minora (Fig. 1-6, I). Last, at the apex of the frenulum, the urethral meatus can usually be found. Fig. 1-6, cont’d G and H, A double clitoral fold inserting into the lateral aspect of the labia minora. I, A lateral double fold that is dominant and continuous with the labia minora. The clitoral body and clitoral hood are hidden. The labia minora continue posteriorly from the clitoral area toward the perineal body either joining to form the posterior fourchette or remaining separate and attaching to the perineum (Fig. 1-7). The appearance and shape of the labia minora have many variations; asymmetries are extremely common, and clinicians specializing in female genital surgery soon become aware that the anatomic variation may be very diverse. Furthermore, the skin quality may vary. Surgeons will note that some patients have youthful and tight labia (see Fig. 1-7, A), but usually, patients presenting for this operation have tissues that are very loose and rugose in nature (Fig. 1-7, B). Often pigmentation is noted. Some of the more common variations of labia minora morphology will be discussed later in the chapter. Fig. 1-7 A, Small, firm labia minora. B, Loose, rugose labia minora. C, Asymmetry within the labia minora. The lateral edge has loose, rugose tissues and pigmentation. Embryologically, the labia majora in women are derived from the genital swellings that, in the male fetus, develop into the scrotum (Fig. 1-8). In contrast, the labia minora develop from the genital folds, which, in the male fetus, fuse to form the median raphe.

Anatomy and Classification of the Female Genitalia: Implications for Surgical Management

Paul E. Banwell

Key Points

Applied Anatomy for Surgeons

Mons Pubis

Labia Majora

The Clitoris

Labia Minora

Embryology

Plastic Surgery Key

Fastest Plastic Surgery & Dermatology Insight Engine