This article provides an overview of the current state of the art of facial reanimation using the best available evidence. Medical, surgical, and physical therapy options in acute and long-standing facial palsy are discussed.

Key points

- •

Management of facial palsy (FP) is dictated by the pattern and time course of dysfunction.

- •

Therapeutic options include pharmaceutical agents, corneal protective measures, physical therapy (PT), chemodenervation agents, fillers, and a myriad of surgical procedures.

- •

Good evidence from well-designed studies supports the use of glucocorticoids and antivirals in the setting of idiopathic and acute viral FP and botulinum toxin (BTX) and PT in the setting of synkinesis.

- •

A plethora of surgical techniques and their respective outcomes have been described in the literature, but few use controls, blinded assessment, and validated scales to reduce bias.

- •

Outcomes research in facial paralysis should comprise standardized subjective quality-of-life (QOL) and objective functional measures.

Introduction/overview

Whether congenital or acquired, FP is a devastating condition with functional and aesthetic sequelae resulting in profound psychosocial and QOL impairment. When acquired, the inciting insult typically results in acute flaccid facial palsy (FFP). Long-term functional outcomes range from full return of normal function to persistent and complete FFP. In between these extremes exist zonal permutations of hypoactivity and hyperactivity and synkinesis; such patterns of dysfunction may collectively be referred to as nonflaccid facial palsy (NFFP). To reduce ambiguity, a summary of pertinent definitions is provided in Table 1 .

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Facial palsy | Term encompassing entire spectrum of facial movement disorders including facial paralysis, flaccid facial palsy, and nonflaccid facial palsy |

| Facial paralysis | Complete absence of facial movement and tone |

| Flaccid facial palsy | Absence or weakness of facial movement and tone, without synkinesis or hyperactivity |

| Nonflaccid facial palsy | A postparetic state whereby aberrant nerve regeneration has occurred, consisting of varying degrees of zonal synkinesis and hypoactivity and hyperactivity |

| Facial synkinesis | Involuntary and abnormal facial muscle activation accompanying volitional or spontaneous expression |

When severe, FFP results in loss of static and dynamic facial symmetry, brow ptosis that obscures vision, paralytic lagophthalmos resulting in exposure keratitis, collapse of the external nasal valve (ENV) impairing nasal breathing, oral incompetence, and articulation impairment. Management is focused on eye protection, restoration of symmetry at rest, and dynamic reanimation. Synkinesis-related symptoms predominate in NFFP, with periocular synkinesis resulting in a narrowed palpebral fissure width that impairs peripheral vision, midfacial synkinesis restricting meaningful smile, and platysmal synkinesis resulting in neck discomfort and facial fatigue. Efforts are concentrated on improving dynamic symmetry.

Introduction/overview

Whether congenital or acquired, FP is a devastating condition with functional and aesthetic sequelae resulting in profound psychosocial and QOL impairment. When acquired, the inciting insult typically results in acute flaccid facial palsy (FFP). Long-term functional outcomes range from full return of normal function to persistent and complete FFP. In between these extremes exist zonal permutations of hypoactivity and hyperactivity and synkinesis; such patterns of dysfunction may collectively be referred to as nonflaccid facial palsy (NFFP). To reduce ambiguity, a summary of pertinent definitions is provided in Table 1 .

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Facial palsy | Term encompassing entire spectrum of facial movement disorders including facial paralysis, flaccid facial palsy, and nonflaccid facial palsy |

| Facial paralysis | Complete absence of facial movement and tone |

| Flaccid facial palsy | Absence or weakness of facial movement and tone, without synkinesis or hyperactivity |

| Nonflaccid facial palsy | A postparetic state whereby aberrant nerve regeneration has occurred, consisting of varying degrees of zonal synkinesis and hypoactivity and hyperactivity |

| Facial synkinesis | Involuntary and abnormal facial muscle activation accompanying volitional or spontaneous expression |

When severe, FFP results in loss of static and dynamic facial symmetry, brow ptosis that obscures vision, paralytic lagophthalmos resulting in exposure keratitis, collapse of the external nasal valve (ENV) impairing nasal breathing, oral incompetence, and articulation impairment. Management is focused on eye protection, restoration of symmetry at rest, and dynamic reanimation. Synkinesis-related symptoms predominate in NFFP, with periocular synkinesis resulting in a narrowed palpebral fissure width that impairs peripheral vision, midfacial synkinesis restricting meaningful smile, and platysmal synkinesis resulting in neck discomfort and facial fatigue. Efforts are concentrated on improving dynamic symmetry.

Therapeutic options and surgical techniques

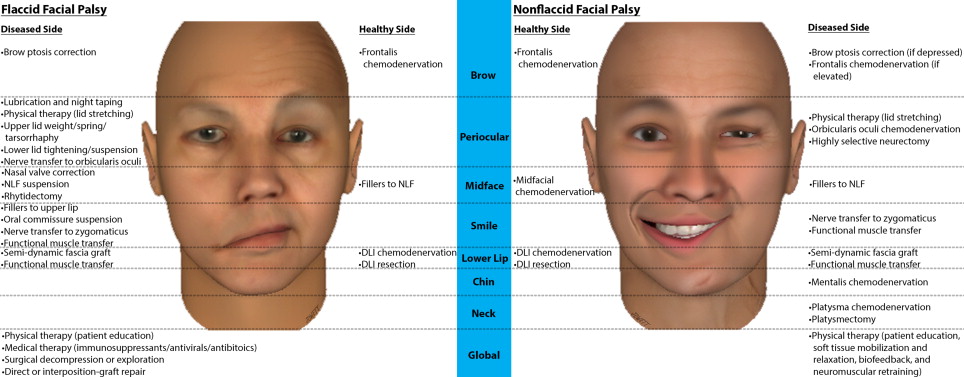

Therapeutic options for FP are dictated by the pattern and time course of dysfunction and may include pharmaceutical agents, corneal protective measures, PT, chemodenervation agents, fillers, and a myriad of surgical procedures. Patients may be classified into 1 of 5 domains: acute FFP, FFP with potential for spontaneous recovery (PSR), persistent FFP with viable or nonviable facial musculature, and NFFP. Fig. 1 summarizes the therapeutic options by zone and side for FFP and NFFP.

The acute setting comprises the first few weeks following onset of FFP whereby medical therapy (immunosuppressants, antivirals, and/or antibiotics), surgical decompression, or neuroplasty may be indicated. Eye lubrication and taping of the eye closed at night is indicated if paralytic lagophthalmos is present to prevent exposure keratopathy, in addition to PT for patient education and upper eyelid stretching to aid passive closure. Correction of paralytic lagophthalmos may be achieved by tarsorrhaphy or by placement of an eyelid spring or weight. Indications include poor prognosis for rapid recovery, inadequate Bell phenomenon, and absent recovery at 3 months. Where nerve continuity is believed to be intact in the setting of FFP, for example, following resection of a vestibular schwannoma (VS) where FN stimulation was achieved before closure, a PSR exists with a plateau expected by 9 to 12 months. Other than corneal protective measures, observation during this period is warranted.

When paralysis persists after nerve insult, native facial musculature is believed to remain receptive to reinnervation for up to 2 years after denervation. During this period, dynamic reanimation procedures using native facial musculature are possible, such as direct repair or interposition grafting of FN stumps (in the setting of an accessible FN discontinuity) or nerve transfer to the distal FN stump or specific branches (where the proximal FN is inaccessible or nonviable). Coaptation of a portion of the ipsilateral hypoglossal nerve to the entire distal FN stump restores resting tone to the face, whereas targeted nerve transfers aim to restore specific volitional facial movements such as smile or blink by coaptation of the donor nerve to the specific distal FN branch controlling the muscle of interest. Common donor nerves for targeted transfer include branches of the contralateral FN (cross-face nerve grafting [CFNG]) or ipsilateral branches of the trigeminal nerve.

When reinnervation of the facial musculature is not possible, therapeutic options in long-standing FFP, in addition to PT and corneal protective measures, include static zonal suspensions, lower eyelid tightening, and dynamic smile reanimation. Targeted suspensions of the brow, lower eyelid, midface, nasal valve, nasolabial fold (NLF), and oral commissure may be achieved using sutures, fascia lata, and bioabsorbable or permanent implants. Tightening of the lower lid may be achieved by the lateral tarsal strip (LTS) procedure with or without medical canthal tendon plication. Dynamic smile reanimation may be achieved through antidromic or orthodromic temporalis muscle transfer or free muscle transfer with motor innervation provided through cranial nerve transfer. Such procedures may be paired with weakening of the normal-side brow or lip depressors or the use of fillers to efface the healthy NLF. Options for dynamic reanimation of the lower lip include anterior digastric muscle transfer, CFNG or split hypoglossal neurotization of the depressor muscles or transferred digastric muscle, and inlay of a T-shaped fascia graft.

NFFP is by definition a chronic condition with intact yet aberrantly reinnervated facial musculature. Lagophthalmos in NFFP is exceedingly rare. PT is first-line treatment; a comprehensive program includes patient education, soft-tissue mobilization, mirror and electromyography (EMG) biofeedback, and neuromuscular retraining. Blunting of hyperactivity through filler injection and weakening of hyperactive muscles through targeted chemodenervation, neurectomy, or resection in advanced disease is indicated in conjunction with PT. In cases with severe restriction of oral commissure excursion, regional innervated muscle transfer, nerve transfer to diseased-side zygomatic branches, or nerve transfer to free muscle may be considered for dynamic smile reanimation.

Clinical outcomes

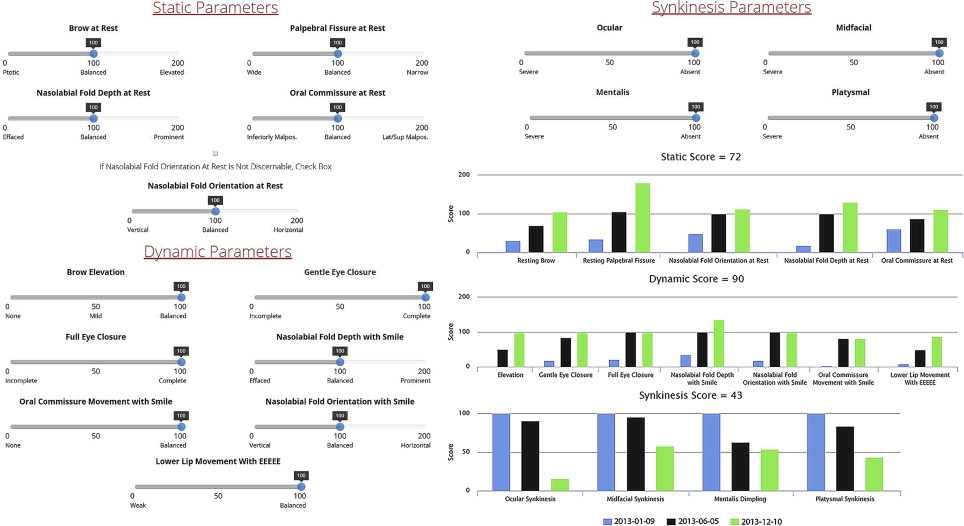

Assessment and reporting of facial outcomes requires a robust means of grading movement. Although 5- or 6-point gross facial function scales, such as the House-Brackmann, Fisch, and others, may be rapidly administered and demonstrate high interrater reliability, they lack the resolution necessary to capture spontaneous or treatment-related zonal changes over time. The Yanagihara scale provides Likert-scale resolution of zonal appearance with movement but not at rest and lacks separate grading of synkinesis. The Sunnybrook facial grading system (FGS) provides weighted scores of zonal symmetry at rest and with motion in addition to synkinesis. A recently validated electronic facial paralysis assessment tool (eFACE) provides even more comprehensive information through weighted clinician-graded continuous visual analog scales of 5 static, 7 dynamic, and 4 synkinetic zonal parameters ( Fig. 2 ). The eFACE tool consists of a database-linked graphical user interface designed for rapid administration using a touch-screen device allowing for immediate graphical representation of results over time. A freeware Java applet (FaceGram, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA, USA) for scaled semiautomated measurements from still images of facial parameters, such as oral commissure excursion and philtral deviation, is useful for quantitative analysis of interventions.

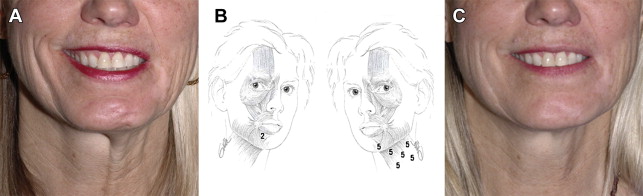

In addition to grading facial movement, standardized assessments of FP-related symptoms and QOL are necessary to track the burden of disease and response to interventions. The patient-graded Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) instrument is useful in patients with ENV collapse secondary to FFP. The NOSE scale consists of patient-reported symptom scores for nasal congestion or stuffiness, blockage or obstruction, trouble with nasal breathing, trouble with sleeping, and trouble with nasal breathing on exertion. QOL impact may be assessed using generalized patient-graded scales such as the SF-36. The Facial Disability Index (FDI) and the Facial Clinimetric Evaluation (FaCE) are patient-graded scales specifically designed and validated for use in FP to concurrently assess symptom severity and impact on QOL, with the FaCE scale demonstrating improved ability to discriminate between patients with FP and normal controls. Figs. 3–10 illustrate a wide range of patient presentations and clinical outcomes following therapeutic interventions.

Clinical evidence

Corneal Protection in Flaccid Facial Palsy

Prevention of exposure keratopathy in the setting of paralytic lagophthalmos is paramount. Patients require instruction on nighttime ointment and tape application to achieve good adherence of the tape to the upper eyelid, to avoid inadvertent eye opening and potential corneal abrasion from the tape itself (level V). For the same reason, patients should be advised to avoid the direct placement of a soft patch over the affected eye. Emerging evidence indicates that a gas-permeable scleral lens worn up to 12 hours a day may be used to treat and prevent exposure keratopathy (level IV).

Pharmaceutical Therapy

When the diagnosis is Bell palsy (BP), there is strong evidence that administration of high-dose glucocorticoids within 72 hours of symptom onset shortens the time to complete recovery in adults (level Ia). Evidence from subgroup analysis has demonstrated improved outcomes for prednisone-equivalent doses totaling 450 mg or higher. Antiviral monotherapy is contraindicated (level Ib). Combined use of antivirals and corticosteroids in BP may be associated with additional clinical benefit, especially for those with severe to complete paralysis (level Ib), with valacyclovir (1 g by mouth 3 times a day for 7–10 days) demonstrating improved time to resolution of acute neuritis over acyclovir. Combination therapy should be used in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)-associated FP (level IV). When FP follows trauma or surgery, it is prudent to use glucocorticoids; however, only noncontrolled case series (level IV) have been reported on their use.

Common infectious causes of FP include Lyme disease and acute otitis media (AOM). FP occurs in 8% of cases of Lyme disease meeting diagnostic criteria established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Targeted antibiotic therapy against Borrelia burgdorferi should always be administered in the setting of a confirmed diagnosis. The Infectious Diseases Society of America has issued guidelines for the clinical assessment and treatment of Lyme disease. Evidence from 2 retrospective studies reveals no benefit from glucocorticoid use in the setting of Lyme disease–associated FP (level IV). AOM-associated FP is managed with targeted antibiotics, myringotomy with or without tube insertion, and mastoidectomy in the presence of coalescent mastoiditis (level IV). When contraindications such as diabetes mellitus are not present, glucocorticoid use in AOM-associated FP is recommended based on case series (level IV) ; however, no controlled studies could be found in the literature.

Surgical Exploration and Decompression in Acute Flaccid Facial Palsy

Evidence has shown that spontaneous return of satisfactory (House-Brackmann grade [HBG] I or II) facial function following BP is reduced by 50% when electroneuronography (ENoG) reveals a greater than 95% difference between sides within 2 weeks of symptom onset. In that prospective controlled (level IIb) study by Fisch, a 30% or greater improvement in satisfactory outcomes in this cohort of patients was achieved when decompression of the site of pathologic constriction, the meatal foramen in 94% of cases, together with neighboring segments via a middle cranial fossa approach was completed within 24 hours of the point where serial ENoG demonstrated 90% to 94% degeneration. A second prospective controlled (level IIb) trial confirmed that surgical decompression that included the meatal foramen resulted in a clinically and statistically significant improvement in long-term outcomes for patients with a diagnosis of BP presenting with severe or complete flaccid paralysis (ie, HBG V or VI), an ENoG response demonstrating greater than 90% degeneration compared with the contralateral healthy side, and absence of voluntary motor unity potentials on EMG. In that study by Gantz and colleagues, 91% of patients meeting the inclusion criteria who underwent decompression within 2 weeks of symptom onset in addition to medical therapy progressed to a final HBG of I or II, compared with 42% of patients who received medical therapy alone ( P = .0002) (level IIb). Both studies were biased by patient self-selection for surgery; this limitation, together with the technical difficulty and associated risks of decompression surgery, such as hearing loss, cerebrospinal leak, and iatrogenic facial nerve injury, prevents consensus on its utilization. Although May and colleagues have advocated that decompression is of no benefit in BP, their conclusions were based on a transmastoid approach in which the meatal foramen was not decompressed.

Others have extended the indications for decompression in BP to VZV-associated and delayed traumatic FFP (level IV), with weak evidence demonstrating benefit even when surgery is delayed by more than 3 weeks (level IV). Exploration is indicated when immediate and unexpected FP arises following surgery in the region of the nerve (level V) and has been advocated in cases in which temporal bone fracture results in immediate facial paralysis, under the assumption that immediate onset indicates nerve transection or impalement by bone fragments. Only noncontrolled case series (level IV) appear in the literature, demonstrating clinical benefit with exploration in the setting of immediate-onset traumatic FP. When combined with the fact that coexisting trauma and neurologic impairment often make it difficult to ascertain whether paralysis is immediate or delayed, the lack of clear evidence indicating benefit leaves the role of surgical exploration and decompression in the setting of temporal trauma unclear.

Observation and Timing of Interventions

Evidence from large retrospective case series has shown that even without treatment, 70% of patients with BP fully recover (ie, HBG 1), 15% recover with only minor deficits (ie, HBG II), and 15% progress to NFFP (ie, HBG III–IV). Persistence of severe or complete FFP (ie, HBG V or VI) in BP does not occur. Evidence from a large retrospective case series has demonstrated that following VS resection with anatomically intact FNs, 94% being via the retrosigmoid approach, all patients with an initial postoperative HBG of III or IV recover without significant deficit (ie, to an HBG of I or II) within 6 to 12 months (level IV). In that same study by Rivas and colleagues, patients having a persistent postoperative HBG of VI at 7 months were noted to have at least an 80% probability of a poor outcome (ie, HBG IV,V, or VI), with this probability approaching 100% by 9 months (level IV), supporting early nerve transfer interventions while facial musculature is still receptive to reinnervation.

Neurorrhaphy

Nerve transections necessitate decision making with regards to timing of repair, need for interposition grafting, and coaptation technique. Following denervation, it has been demonstrated in animal models that neuromuscular junctions become progressively less receptive to regenerating motor axons. Evidence from case series suggests that the time to reinnervation is likely the most important factor and that delays longer than 12 to 24 months result in significantly worse mimetic outcomes (level IV). Increasing age has also been shown to result in decreasing capacity for neuron survival, neural regeneration, and/or muscle receptivity to reinnervation following injury in animal models. It follows that reconnection of viable motor axons to facial musculature should proceed without delay in the setting of known neural discontinuity. When presentation is delayed or when no recovery of function occurs following injury not resulting in transection, no definitive criteria exist for predicting the degree to which the facial musculature remains receptive to reinnervation. Postoperative radiation therapy has been shown to have negligible impact on neural regeneration and ultimate mimetic outcomes in animal models and in clinical case series (level IV); as such, it should play no role in decision making with regards to neurorrhaphy.

Many surgeons use a threshold gap of 5 mm to prompt the use of an interposition graft. Evidence from animal studies demonstrates a clear inverse relationship between tension across the repair site and outcomes ; better outcomes are achieved using a cable graft of suitable diameter when direct end-to-end repair would result in a tension exceeding 0.3 to 0.4 N across defects 6 mm or greater. Although many surgeons inlay grafts in reverse polarity, based on the presumption that this results in fewer regenerating axons being lost along exiting branches, evidence for this practice is lacking; most animal studies have shown no dependency of electrophysiologic, histologic, or functional outcome measures on graft polarity. One animal study demonstrated decreased graft cross-sectional area with orthodromic compared with antidromic positioning ; however, this study was severely limited by lack of functional outcomes measures and axonal counts. Clinical case series have demonstrated worse facial nerve functional outcomes with interposition grafting in older patients than in younger patients (<30–60 years of age) (level IV).

Coaptation technique is an important consideration. Evidence from animal models has demonstrated no statistical difference in functional or electrophysiologic outcomes between interfascicular and epineurial neurorrhaphy following transection. Histologic studies have demonstrated increased neuroma lengths at neurorrhaphy sites resulting from interfascicular compared with epineurial repair without statistical difference in myelinated fiber counts between groups in the distal segment 12 months following repair. Use of fibrin adhesive in comparison with microsutures for nerve transection repair and cable graft coaptation has demonstrated equivalent functional and long-term histologic outcomes in the vast majority of randomized controlled studies in animal models while offering the advantage of reduced operating time ; however, a minority of studies have demonstrated statistically inferior electrophysiologic outcomes, with one demonstrating decreased axon counts in the case in which fibrin glue was used as opposed to nylon microsutures. High-quality human studies comparing coaptation using fibrin glue with conventional epineurial suture repair are lacking; retrospective reviews have demonstrated equivalent functional outcomes for fibrin glue repair of brachial plexus and digital nerves (level IV) and the facial nerve. Cyanoacrylate should not be used for nerve coaptation, as it causes a profound foreign-body inflammatory reaction and subsequent fibrosis (level V).

Physiotherapy

Despite the conclusions of a 2011 meta-analysis, good evidence supports the use of PT in FP. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Beurskens and colleagues, patients with long-standing NFFP following BP, AN resection, VZV infection, and trauma receiving 3 months of comprehensive facial PT as opposed to being waitlisted demonstrated statistical improvements in patient-reported facial stiffness and FDI scores and quantitative assessment of lip length; however, no statistical benefit was seen in blinded expert-assessed FGS scores 12 months after therapy (level Ib). In the 2014 RCT by Pourmomeny and colleagues, patients with acute FFP (onset within 3 weeks) resulting from BP, trauma, or tumor extraction who received PT that included EMG biofeedback demonstrated significantly improved FGS scores at 1 year compared with those receiving PT without EBF (77 ± 16 vs 56 ± 27, P <.05); however, those assessing FGS were not blinded (level Ib). In that same study, further assessment by 1 blinded reviewer of synkinesis based on a custom scale demonstrated that 31% of patients who received PT that included EBF demonstrated moderate to severe synkinesis at 1 year compared with 77% of patients who received PT that did not include EBF (relative risk, 0.41, 95% confidence interval, 0.19–0.89) (level Ib). An RCT by Nicastri and colleagues demonstrated that 74% of patients with BP presenting with severe to complete FFP (ie, HBG V/VI) who received combination pharmacologic therapy (CPT) with prednisone and valacyclovir plus comprehensive PT within 10 days of symptom onset progressed to an HBG of I or II as assessed by 1 blinded expert within 6 months, compared with only 48% of those receiving CPT alone (adjusted P = .038) (level Ib). In summary, recent evidence supports the use of PT in acute FFP and long-standing NFFP.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree