In the past decade, the aesthetic dermatology marketplace has undergone an explosive expansion. Despite recent and increasingly difficult economic times, the demand for cosmetic procedures to enhance, rejuvenate, or maintain beauty standards continues to grow. Since 2000, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three neurotoxins and over twenty dermal filler devices, which are indicated for the treatment of soft tissue augmentation and temporary improvement of wrinkles associated with muscle movement and volume loss. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) reported that 1.1 billion dollars was spent on cosmetic procedures in 2012, which is a 5.5% increase from 2011, and office procedures performed by plastic surgeons grew by 10%. According to the ASPS, an estimated 14.6 million cosmetic procedures were performed in the United States in a medical office setting. Of the total estimated procedures, 1.6 million were defined as cosmetic surgical procedures, 13 million as cosmetic minimally invasive procedures (

Table 23-1), and 5.6 million reconstructive procedures. Men and women, 40 to 54 years of age, are the largest demographic groups of the minimally invasive procedures, accounting for 48% of the cosmetic procedures. A 3% increase from 2011 was noted in minimally invasive procedures in females from the ages of 13 to 39. Females represent 91% of the paying consumers seeking cosmetic procedures, and males represent 9% of cosmetic procedures.

The accelerated growth of the overall beauty industry and the recent increase in the FDA approval of medical devices, dermal fillers, and neurotoxins have blurred the lines between traditional medical interventions, elective procedures, and beauty services. The brisk influx of products and services to the marketplace and the ever-increasing use of off-label indications of approved devices and therapies present a unique educational dilemma to establish competency for providers of aesthetic products and services.

The Dermatology Landscape

The specialty of dermatology has undergone a dramatic evolution over the past decade, including the introduction of aesthetic medicine. It is common for medical and surgical specialties, as well as individual providers, to claim expertise and ownership of lucrative cash-based aesthetic procedures and services. While there is no question that the demand for these services is present and the financial gains are obvious, it is imperative to have formal training, core competencies, and credentialing for providers to ensure safe and efficacious practice. Regardless of the clinician’s educational pedigree, the lack of competency specific to aesthetic services equates to an increased risk for poor outcomes and decreased safety for patients.

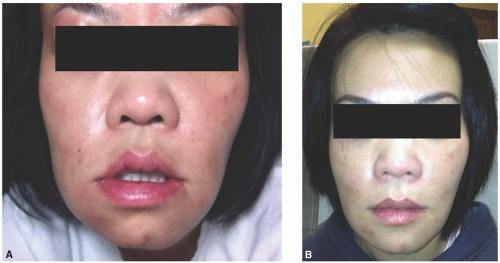

The science and art of aesthetics goes beyond the knowledge and skills of procedures and requires that clinicians assess and discern patients who are at risk for, or are suffering from, a psychiatric disorder. Patients seeking multiple aesthetic procedures have the highest risk for depression, anxiety, mood disorders, personality disorders, and body dysmorphia (BDD).

BDD is characterized by preoccupation with perceived appearance defect(s), with excessive concern over any slight physical anomaly, as well as significant distress or impairment in functioning that is not accounted for by a diagnosis such as anorexia nervosa. Because these patients have unyielding negative perceptions about their appearance, they are at risk for poly-procedures from multiple providers. When the clinician does not perceive the same defect or severity as the patient, it is a hallmark warning for BDD. Patients’ intrusive obsessions about their physical appearance can occupy an inordinate amount of their time and focus. The pervasive distortion can magnify poor self-image, esteem, avoidance, and interference with daily living. This can lead to extreme behaviors where they seek

multiple procedures from different specialists. It can also include suicidal ideation.

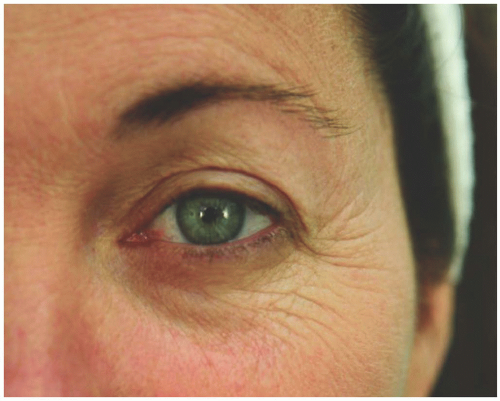

When assessing a patient at risk for BDD, remember that he or she will engage in camouflaging behaviors such as body position and use of hats, hair, makeup, glasses, etc. Patients will often be distracted during an examination to gaze at themselves in reflective surfaces such as spoons, mirrors, or windows. Other patients may avoid mirrors as their reflection is so disturbing to them. Other obsessive compulsive behaviors, including skin picking, excessive exercising, and changing clothes repeatedly throughout the day, may be reported.

Clinicians must establish safe and strong boundaries with patients who have BDD by limiting their procedures. Be aware that patients may seek drastic alternatives such as buying products from the black market in an attempt to self-treat (

Figure 23-1). Hence, a safe and successful aesthetic practice begins with a careful assessment of the patient’s motivation to enhance or modify their appearance long before the initiation of any procedure. Depression and anxiety screening tools can be incorporated into an assessment if there is any suspicion for BDD. A collaborative approach, including psychiatry and counseling, is recommended.

Clinicians practicing aesthetics should take note that despite high quality education, training, and good patient screening, aesthetic patients are known to be high risk for litigious actions. The result is increased premiums for professional malpractice insurance for clinicians providing cosmetic services.

FDA Intervention in Aesthetic Devices

In 2008, the device arm of the FDA convened a panel of dermatology experts to examine the increasing trends of adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) reported as a result of soft tissue augmentation devices. Most of the AEs and SAEs reported were from off-label use of products (

Dang, Francis, Durfor, Mirsaidi, & Shoaibi, 2008). The FDA advisory panel has recommended changes in the clinical trials process of products and the AEs reporting system. It also acknowledged that dermatology, as a specialty, had been scrutinized when in reality these devices were being used by many nondermatology physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses. One of the panel’s recommendations was that manufacturers restrict the sale of their products to dermatologists and plastic surgeons. Many manufacturers require that a clinician have a valid Drug Enforcement Agency number and a state medical license to purchase their products.

FDA Labeling

The reality of aesthetic services is that most procedures for soft tissue augmentation and neurotoxins are performed off label and lack the data or evidence required by the FDA to approve the product or device for both safety and efficacy. Although manufacturers may have clinical data that have been gathered and studied outside of the FDA approval processes, use of the product or device is still considered off label. It is both cost prohibitive and time sensitive for manufacturers to submit every indication to the FDA for approval. Accordingly, one must carefully weigh the risk versus benefits before deciding to perform procedures outside of FDA-labeled indications. This includes black-box warnings, contraindications, other warnings, and precautions. In the event of an adverse outcome, the assumption of legal risk is compounded.