CHAPTER 7 Aesthetic Surgery of the Face

Introduction

In Chapter 6, we looked at aging changes around the eyes from the point of view of restoring the function of the eyes lost with the common aging changes. We have looked primarily at the upper face, the forehead, and upper eyelids and some procedures to improve eyebrow position and remove the extra skin on the eyelid. In this chapter, we will reinforce the concepts that you have already learned with regard to the upper face. We’ll look at the mid and lower face. At the same time, we’ll put the sags, bags and wrinkles that we see in the framework of the “descent and deflation” process that begins and continues through adulthood.

As always keep the big picture in mind. Skim over the material initially and go back over it in a more detailed fashion. Pick out areas that you and your patients are interested in. Start with easy skin care options and proceed to the next level when your skills permit it. For more advanced operations, you will need extra reading, observation, and mentoring before you take them on. At the end of this chapter, no matter what your personal goals are in the area of facial rejuvenation, you should have a good base to build on.

Evaluation and treatment of aging

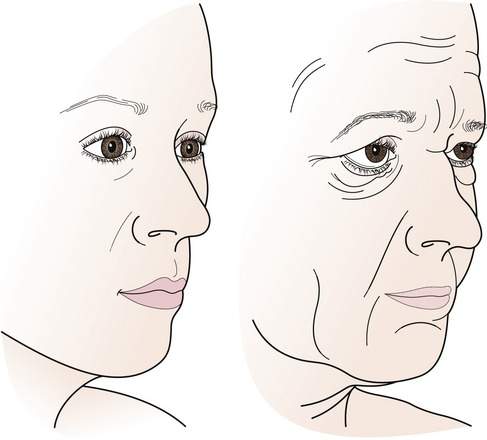

What happens in aging? The conceptual approach of “descent and deflation” is a good way to organize your thoughts. As we age, supporting tissues stretch causing the familiar “sags and bags” of aging. Accompanying this laxity is a general loss of soft tissue thickness. In the current jargon, this is referred to as a loss of facial “volume.” A combination of thinning of the subcutaneous layer and facial fat pads combines with generalized tissue laxity to give a characteristic aged facial profile. Temporal brow drooping and the formation of the melolabial fold are familiar examples. Thinning of the skin, primarily the dermis, causes the skin to “wrinkle” and develop other surface changes (Figure 7-1).

There is a complex interplay of internal and external causes of aging. Forgive this simplification, but I think you will find that this scheme will provide a basis for evaluating your patient’s aging changes. You will also see that these concepts will help you organize and present a treatment plan to your patient (Boxes 7-1, 7-2 and 7-3).

Anatomic considerations

The skin

In Chapter 2, we discussed the facial anatomy in some detail. Here, we will review features that you can easily apply to the sags, bags and wrinkles approach to the evaluation and treatment of your patients. We will start at the surface and work our way inward.

The dermis is a connective tissue layer made of collagen and elastin fibers surrounded by a watery mixture known as the ground substance. The dermis also contains fibrous cells and the skin adnexae—the hair follicles, oil and sweat glands. We will discuss a variety of lesions related to the adnexae in Chapter 11. Blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves also travel within the dermis.

Superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS)

In Chapter 2, we spent a great deal of energy talking about the muscles of facial expression and the investing fibrous layer known as the SMAS (superficial musculoaponeurotic system). If this is sounding pretty hazy to you, it might be worth going back and rereading the last sections in Chapter 2 before you move on. Hopefully, you will recall that the SMAS layer coordinates facial movements by physically linking the mimetic muscles together. Strong fibers attach the SMAS to the underlying bone and in turn attach to the skin itself (osseo-cutaneous retaining ligaments). These ligaments are strongest along the inferior and lateral orbital rim extending onto the zygoma, as well as along the mandible. Lax tissues “hang” over the sturdy attachment points. Combined with the loss of associated fatty tissues, this process is responsible for the characteristic “sags and bags” of the face—deepening of the melolabial fold, jowling, and marionette lines. The anatomic extensions of the SMAS—the temporoparietal fascia (TPF), the galea, and platysma—develop laxity as well. Temporal brow drooping and platysmal banding are the manifestations of this process.

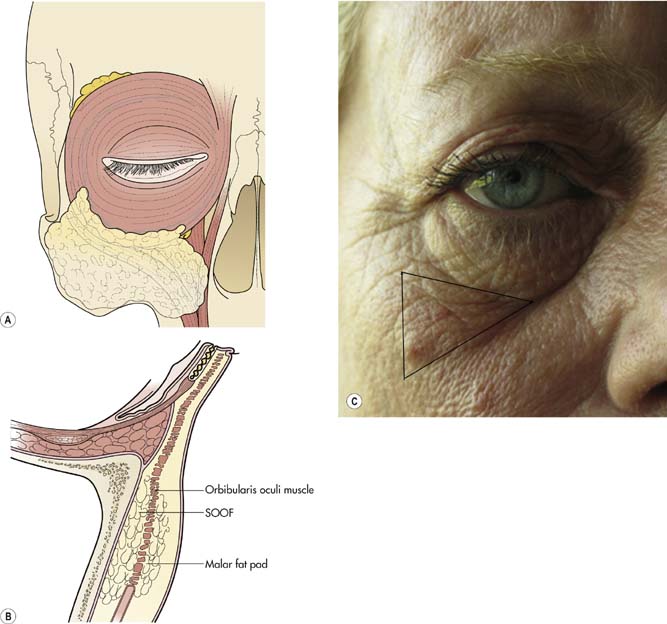

As the SMAS stretches, its associated fat pads fall, contributing to the sags and bags we have just discussed. A deep plane of fat exists behind the orbicularis muscle overlying the inferior rim (the suborbicularis oculi fat pad; SOOF) and extends superiorly over the lateral rim to overlie the superior orbital rim (the retroorbicularis fat pad; ROOF). The fullness of the lateral portion of the eyebrow and the tissues over the superior orbital rim seen in youth are due to a full and well-supported ROOF. Drooping of the ROOF is a cause of temporal eyebrow ptosis and is corrected with the browplasty or forehead lift operations. The malar fat pad is a collection of fat on and within the anterior surface of the SMAS over the malar eminence (Figure 7-2). A full normally positioned malar fat pad contributes to the high full cheek in children and young adults. We will see below that the descent of the SOOF and the malar fat pad is a characteristic feature of facial aging, the formation of the so-called double convexity deformity.

In the child, the facial profile from the lower eyelid to the cheek extends inferiorly in a smooth convexity (Figure 7-2). Over time, this single curve changes into a double curve. Here is what happens. Let’s look at the development of the cheek convexity first. As the SMAS stretches in the lateral midface, the malar and the suborbicularis fat pads fall (“descend”) in a characteristic manner creating the “malar mound” laterally. Medially, the cheek descent causes the inferior orbital rim to lose its soft tissue padding (part of the “deflation” look). This used to be referred to as a “long lower eyelid.” Now the term “skeletonization” of the lower orbital rim is in vogue, emphasizing the loss of tissue over the inferior orbital rim. The feature most commonly emphasized is deepening of the nasojugal fold (so-called “tear trough” deformity). As the cheek tissues descend inferiorly and medially, the melolabial fold deepens. The eyelid convexity develops as the orbital septum thins and fat prolapses forward. The aging adult develops a bulge of fat prolapse in the lower eyelid, a hollow at the rim, and a bulge of drooping cheek, the double convexity.

My hope is that by now you are starting to understand the normal anatomy and what happens to that anatomy with aging. The options for rejuvenation are numerous and complex. So how do you decide what can or should be done? Let’s look at the options from simplest to more complicated. As you might imagine, this algorithm follows a chronological progression of patient age (Table 7-1).

Table 7-1 Options for rejuvenation

| Prevention | ||

| Wrinkles | Sunscreen and stop smoking | All ages |

| Dynamic wrinkles | Botulinum injection | 30–40+ years |

| Adynamic wrinkles | Fillers | 40+ years |

| Surface texture and color changes | Laser resurfacing or chemical peels | 40+ years |

| Sags and bags | ||

| Dermatochalasis | Blepharoplasty | 35+ years |

| Lower eyelid fat prolapse | Blepharoplasty | 35+ years |

| Brow ptosis | Browplasty or forehead lift | 40–50+ years |

| Deepening of melolabial fold | Midface lift | 40–50+ years |

| Jowling and marionette lines | Facelift | 50+ years |

| Platysmal banding | Liposuction and platysmaplasty | 50+ years |

Checkpoint

• What do we mean by intrinsic and extrinsic causes of aging?

• What are the two main extrinsic causes of aging?

• What is the difference between dynamic and adynamic wrinkles?

• Do you understand the concept of “descent and deflation”?

• Starting with the forehead, describe some characteristic “sags and bags”

Making a decision: the “cost”–benefit ratio

The menu

All patients over 40 years have some degree of all these aging changes. So how do you and your patient make a decision about which of many choices for rejuvenation is appropriate? It all comes down to the perceived cost–benefit ratio. You are going to offer only procedures within your skill set that you think will address the patient concern and offer a benefit to the patient with a minimal risk. As we said, your job is to educate the patient with regard to the benefit and risk of a particular procedure. As cosmetic procedures are completely elective, the decision to proceed really comes down to the patient’s perception of the cost–benefit ratio. If the patient perceives no benefit, even “no risk” does not make the patient want to have the procedure (mind set 1). If the patient perceives a benefit and the risks appear minimal, he or she will elect to proceed with surgery.

Where do you start?

In the next sections, we will consider the first of these procedures in some detail. I would like you to have an understanding of midface, lower face, and neck lifting procedures, but have not given you details. There are many other procedures that you should at least be aware of, such as cheek and chin implants, rhinoplasty, and hair replacement, that are not covered in this text. There are many texts available that you can use when you want more specifics. Some of these are listed in the Suggested Reading. Before we head toward the procedures, we should talk about prevention of facial aging, an important topic for all our patients for both functional and aesthetic reasons (Box 7-4).

Prevention and medical treatment of the skin

Keep in mind our scheme for evaluation and treatment. Is your patient concerned about wrinkles or sags and bags? We will talk about how to improve the wrinkles with Botox injection, injectable fillers, and skin resurfacing in the next sections. Later in the chapter, we will discuss some of the surgical procedures for rejuvenating your patient who complains of sags and bags (Box 7-5).

Botulinum (Botox®) injection

Principles

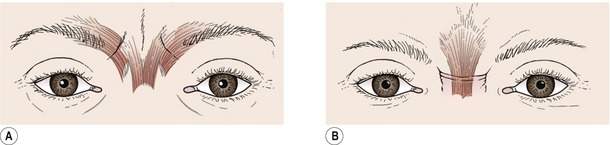

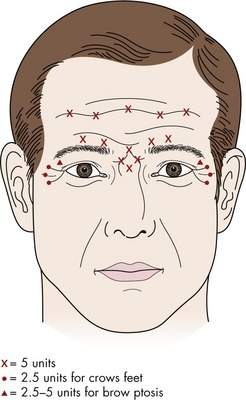

Wrinkles in the skin are caused by contraction of the underlying muscles. As we have shown earlier, the wrinkling is directed 90 degrees from the pull of the underlying muscles. Think of the horizontal forehead rhytids resulting from the contraction of the underlying vertically oriented frontalis muscle or the radially oriented crow’s feet at the lateral canthus resulting from circular orientation of the underlying orbicularis muscle. In Chapter 2, we talked about the glabellar wrinkling causing contraction of the underlying procerus and corrugator muscles (Figure 7-3). In youth, the plump skin barely shows a wrinkle with facial movement. As the skin thins, facial movements are accompanied by “dynamic wrinkles.” With further aging and loss of the elastic nature of the skin, wrinkles present without muscle contraction develop, known as “adynamic wrinkles.” As Botox blocks the underlying muscle contraction, it is most useful for the treatment of dynamic wrinkles. The primary regions where Botox is used are in the forehead, glabella, and crow’s feet.

Technique

Botox is available in a powder form with 100 u of Botox in each bottle. The powder is typically dissolved with 2 cc of sterile saline (resulting in a dilution of 5 u/0.1 cc of fluid). You should avoid vigorous shaking of the bottle as the Botox is easily degraded. Typically 2.5–5.0 units are injected in each site. (0.05–0.10 cc of solution). Some surgeons change the concentration depending on the site. Typical injection sites and dosage are chosen as shown in Figure 7-4. You might want to review the sites for Botox injection in cases of essential blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm shown in Chapter 9 (Figures 9-8 and 9-9).

A good rule of thumb is—Botox is best for the upper face. Fillers are best for the lower face.

Injectable fillers

Principles

Injection into the crow’s feet or the melolabial folds is the easiest. When you get more experience, you can inject the nasojugal fold and the lips. Small depressed scars can be improved somewhat. If adynamic wrinkles remain after Botox injection into the forehead and glabella, you can add a small amount of filler (especially in men with deep wrinkles). Check out the tips for injection of HA fillers in Box 7-6.

Most “permanent filler” products contain particulate matter and derive their long-lasting effect by stimulating new collagen production in the dermis. The effect is delayed and cumulative over many injections. These fillers should be delivered deeper in the dermis. There is no current consensus on the safest and most effective type of long duration filler product at this time. None are FDA approved for cosmetic use except for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) lipodystrophy patients. The benefit of a “permanent” effect is attractive to patients, but there is no good way to reverse an unwanted outcome. Rare, but reported, side-effects, such as granuloma formation, are difficult to deal with. I would suggest that you do not use these materials until you are very comfortable with your techniques using HA products.

My goal in this section is to have you remember the principles of Botox and injectable filler use. Botox and fillers are a good place to start your aesthetic practice. Patients with less aged skin may have only dynamic wrinkles and respond well to Botox alone. Patients with more aged skin will have both dynamic and adynamic wrinkles. If Botox alone does not do enough, you can add an HA-based filler. The currently available products are listed in Box 7-7. Start with one or two HA products and get confident using them. As you get more experience, you might want to learn to use longer lasting fillers. Keep in mind that this field is changing rapidly, so check the literature and talk with your colleagues to find out the latest information on the effectiveness, duration, and safety of new products as they become available (http://www.juvedermusa.com, http://www.restylaneusa.com).

Technique

Checkpoint

• Think about your personal philosophy regarding “cosmetic surgery” for your patients. Start thinking about the menu of aesthetic treatments you may want to offer

• Name two types of skin products that help prevent aging changes—are you using them?

• What is the difference between dynamic and adynamic wrinkles?

• Remember, Botox for upper face, fillers for the lower face. As you get more experience, you can “bend” the rules

• Sketch out potential sites for Botox

• Sketch out the potential sites for filler injection

• Why should you use fillers with caution in the glabella?

Skin resurfacing and chemical peeling

Fitzpatrick classification system of skin type

The Fitzpatrick Classification (Table 7-2) is useful for selecting which of your patients are good candidates for treatment. This classification is based on a patient’s tendency to tan rather than burn when exposed to sunlight. Your patients with lighter skin color will respond best to resurfacing and peeling procedures with less risk of post-treatment hyperpigmentation, the most common side-effect. When you are learning these treatments, pick patients with mild to moderate aging changes with skin types I–III. You will get a reasonable effect and will avoid unwelcome post-treatment pigmentary changes.

Table 7-2 Fitzpatrick Classification System

| Skin type | Skin color | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| I | Very white or freckled | Always burns, never tans |

| II | White | Usually burns, tans less than average |

| III | White to olive | Sometimes mild burn, tans about average |

| IV | Brown | Rarely burns, tans more than average |

| V | Dark brown | Rarely burns, tans profusely |

| VI | Black | Never burns, deeply pigmented |

Laser resurfacing

Laser energy can be used to improve skin texture, pigmentation, and wrinkling. Many types of lasers and techniques have been described in recent years to improve facial skin health. In my opinion, the gold standard remains the CO2 laser ablative resurfacing technique*. The chromophore for the CO2 laser is water (10,600 nm wavelength). As human tissues contain a large amount of water, high laser energy levels will instantly vaporize the tissue. When lower energy is absorbed, the tissues will absorb heat. Ablative resurfacing techniques (either CO2 or Erbium YAG) vaporize the epithelium and deliver heat into the dermis. As the new epithelium regenerates, the result is a smooth healthy layer of cells without blotchy pigmentation. During the recovery process, the underlying dermis goes through a remodeling process that promotes collagen production resulting in a more plump skin with fewer wrinkles. Recently, nonablative lasers have been developed that deliver energy to the deeper layers without removing the surface epithelium. The intended result is improvement of wrinkles without the crusty healing phase of epithelialization. As you might expect, the result is faster healing, but a less dramatic reduction in wrinkling. More recently, laser techniques have developed known as fractional resurfacing. Using this technology, microscopic “holes” are burned through the epithelium with most of the energy delivered deeply. The consensus opinion regarding the results of this technique is not in yet. No doubt there will be continued efforts to achieve the most improvement with the least “down time” and possible side-effects. There is no “right” technique or laser.

With experience, you will learn how to modify the settings or add treatment passes. When preparing to treat your patient, select the appropriate settings, get a comfortable grip on the hand piece, and fire a test against a tongue blade to see that the laser is working correctly. Depress the foot pedal for each laser burst. As you get experience, you can use repeated timed firings by holding the pedal down. Position the hand piece with the laser aimed perpendicular to the skin surface. Most lasers have a collimated hand piece that does not require an exact focal distance, making your hand positioning more flexible. Put the laser pattern bursts next to each other on the skin, with about a 10% overlap. When you complete one pass of the entire treatment area, you should remove the charred epithelium with a soaking wet gauze pad. Dry the skin to remove all water before another pass (Figure 7-5).

A general protocol is presented in Box 7-8.

Box 7-8 CO2 Laser Resurfacing for Mild to Moderate Sun Damage

Pretreatment

6 weeks before—Tretinoin 0.05% bid for 6 weeks

2 days before—and continued until epithelialized

Treatment

Safety precautions—eye glasses for staff, wet drapes around field and over any endotracheal tube, metal contact lenses for patient, wet gauze over teeth CO2 laser* settings with computer pattern generator hand piece