Chapter 14 Aesthetic Contouring of the Craniofacial Skeleton

Introduction

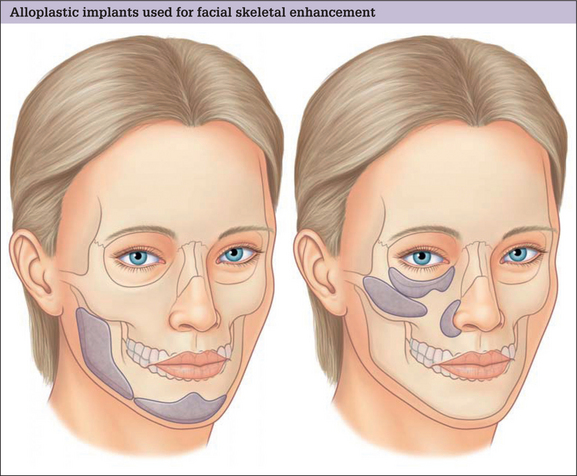

Augmentation is the predominant means of aesthetic contouring of the facial skeleton in non-Asian populations. Conceptually, autogenous bone would be the best material for augmentation, because it has the potential to be revascularized and, then, incorporated into the facial skeleton. In time, it could be biologically indistinguishable from the adjacent native skeleton. Practically, the use of autogenous bone is limited. The morbidity, time and hospital costs associated with autogenous bone graft harvest can be significant. Furthermore, the inevitable resorption and the poor handling characteristics of autogenous bone grafts also limit the quality and predictability of the aesthetic result. For these reasons, almost all facial skeletal augmentation is done with alloplastic implants. A diagrammatic survey of the facial skeletal areas amenable to augmentation with alloplastic implants is presented in Fig. 14.1.

Indications

Preoperative Evaluation

Radiology

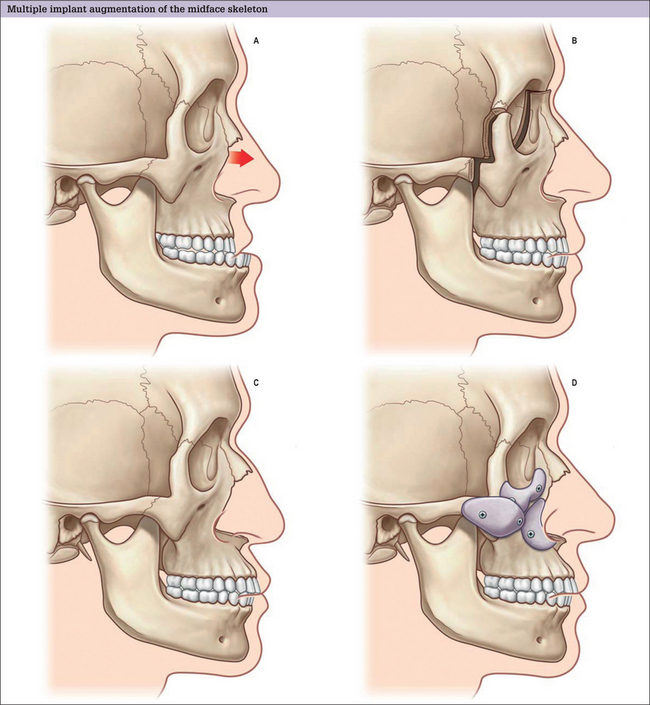

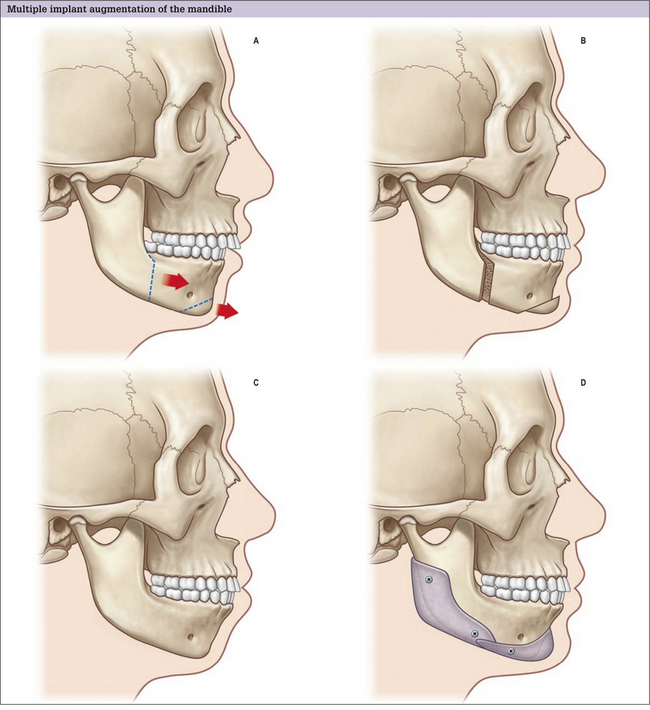

Most aesthetic procedures are done without preoperative radiology assessment. In general, the size and position of the implant are largely aesthetic judgments. Cephalometric X-rays are most often used for planning chin and mandible augmentation surgery. These studies define skeletal dimensions and asymmetries as well as the thickness of the chin pad. Computerized tomographic (CT) scans provide the ability to view the skeleton in different planes and, through computer manipulation, in three dimensions. CT imaging provides digitized information that can be transferred to design software. This can be used to create life-sized models and custom implants, which are particularly helpful when augmenting facial skeletons with significant asymmetries.

Surgical Planning

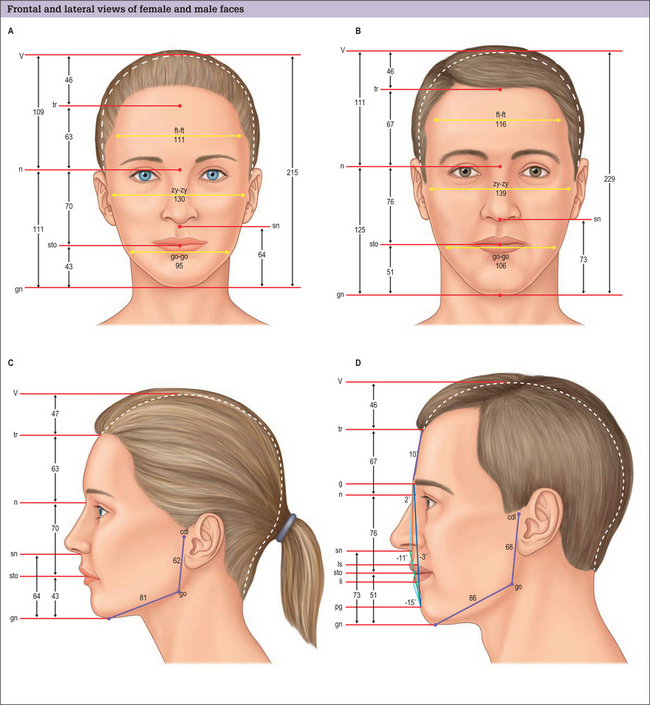

Facial anthropometries and neoclassical canons

For purposes of painting and sculpture, Renaissance scholars and artists formulated ideal proportions and relations of the head and face. These were largely based on classical Greek canons. Although usually referenced in texts discussing facial skeletal augmentation, neoclassical canons have a limited role in surgical evaluation and planning, because they are based on idealizations. When the dimensions of normal males and females were evaluated and compared to these artistic ideals, it was found that some theoretic proportions are never found, and others are one of many variations found in healthy normals, or those determined more attractive than normals.1,2 The neoclassical canons do not allow for the facial dimensions that are known to differ with sex and age. Most of these canons of proportion (e.g. the width of the upper face is equal to five eye widths), are interesting but hold for few individuals and cannot be obtained surgically or, if obtainable, only with extremely sophisticated craniofacial procedures. For these reasons, we have found it more useful to use the anthropometric measurements of normal individuals to guide our Gestalt in the selection of implants for facial skeletal augmentation (Fig. 14.4).3 Normal dimensioned faces are intrinsically balanced. That is, the relations between the various areas of the face relate to one another in a way that is not distracting to the observer. By comparing a patient’s dimensions to the average, the surgeon has some objective basis as to what anatomic area may be amenable to augmentation, and by how much.

Alloplastic Materials

Implant materials used for facial skeletal augmentation are biocompatible – that is, there is an acceptable reaction between the material and the host. In general, the host has little or no enzymatic ability to degrade the implant with the result that the implant tends to maintain its volume and shape. Likewise, the implant has a small and predictable effect on the host tissues that surround it. This type of relationship is an advantage over the use of autogenous bone or cartilage which, when revascularized, will be remodeled to varying degrees, thereby changing volume and shape.

The presently used alloplastic implants used for facial reconstruction have not been shown to have any toxic effects on the host.4 The host responds to these materials by forming a fibrous capsule around the implant, which is the body’s way of isolating the implant from the host. The most important implant characteristic that determines the nature of the encapsulation is the implant’s surface characteristics. Smooth implants result in the formation of smooth-walled capsules. Porous implants allow varying degrees of soft tissue ingrowth that results in a less dense and defined capsule. It is a clinical impression that porous implants, as a result of fibrous incorporation rather than encapsulation, have a lower tendency to erode underlying bone or migrate due to soft tissue mechanical forces and, perhaps, are less susceptible to infection when challenged with an inoculum of bacteria. The most commonly used, commercially available materials today for facial skeletal augmentation are solid silicone, and porous polyethylene -Medpor (Porex, Fairborn, GA). Eppley5 has summarized the attributes of these materials.