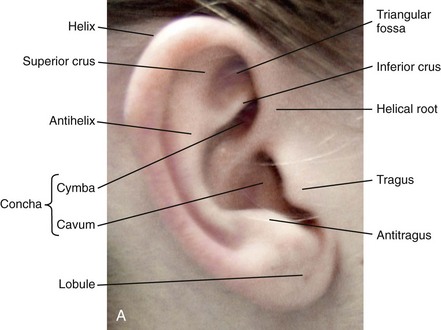

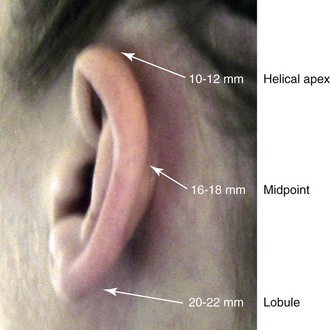

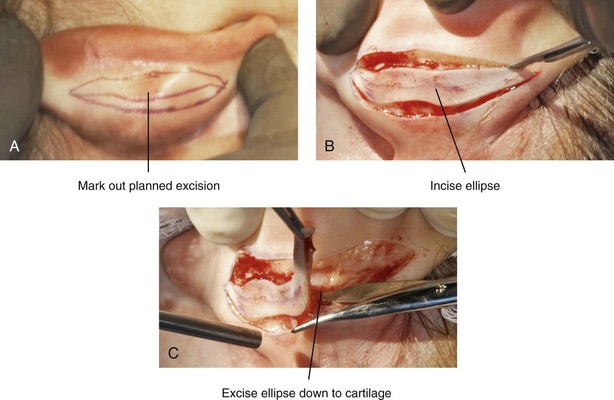

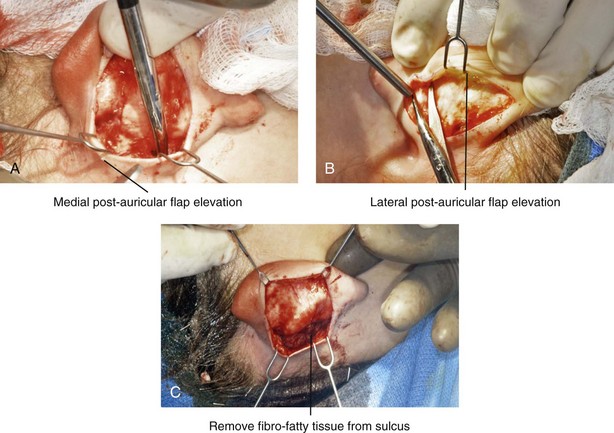

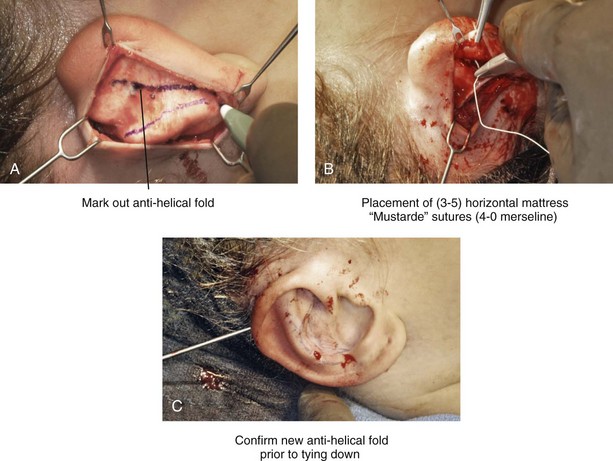

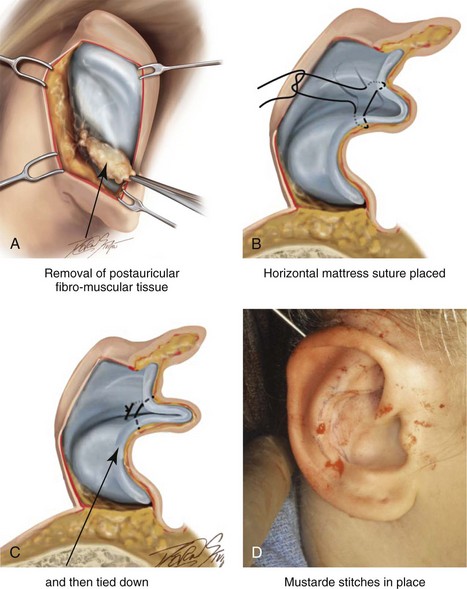

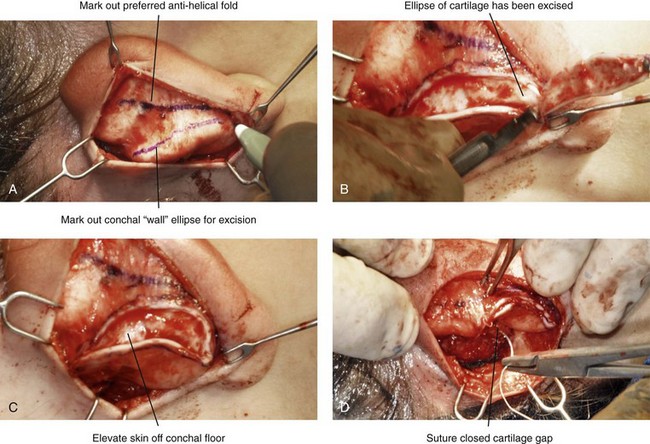

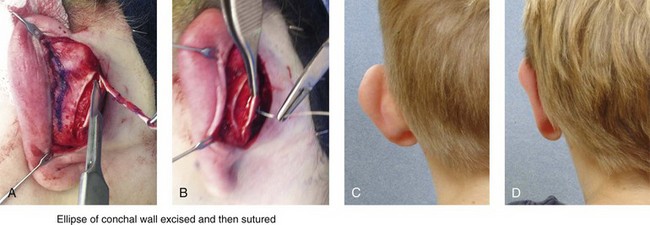

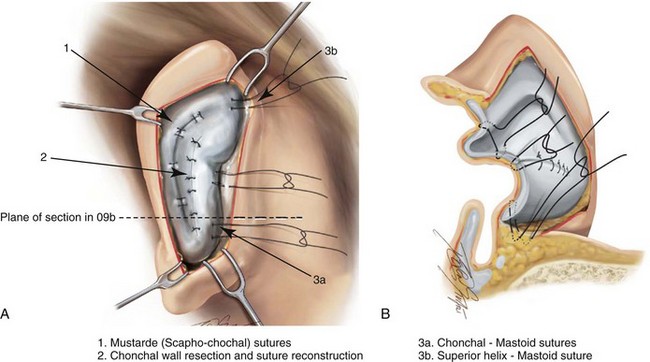

39 Aside from the excision of auricular tags and the repair of traumatically clefted ear lobes, the prominent ear is the most commonly treated external ear deformity. Approximately 5% of the Caucasian population has protruding ears, thereby making this the most frequent congenital anomaly of the external ear. Otoplasty is a common aesthetic operation that is carried out among children and adolescents to address this issue. There is a wide variation with regard to what is considered normal for ear size, prominence, and shape (Fig. 39-1). An “outstanding” ear is said to be present when the distance of the helical rim from the temporomastoid surface of the skull is excessive. As a general rule, a measurement of more than 16 to 21 mm is said to result in a prominent ear (Fig. 39-2). The average ear is 6.5 cm long and 3.5 cm wide, but significant variations are considered acceptable. After the completion of normal ear growth and with ongoing age, the external ear changes in that the elongation of the soft tissue covering and the earlobe is to be expected. Provided that the ear has a morphology that is in balance with the other facial features and that there is reasonable symmetry from one ear to the other, these variations are considered to be in an acceptable aesthetic range. However, when ear shape, size, and proportion are perceived as distracting to the casual observer at conversational distance, the ears may become a source of ridicule and personal anguish. Affected children are frequently stigmatized by their peers and commonly ask their parents if a solution for their visible abnormal ear shape can be found. In these circumstances, the surgical correction of the prominent ear is likely to have a beneficial effect on the person’s self-esteem and body image. Figure 39-1 A, The topographic anatomy of the external ear is shown. Key anatomic landmarks are demonstrated and labeled. B, Drawing by Leonard da Vinci that confirms the importance of achieving Euclidian proportions of the external ear within the face. Figure 39-2 Ear protrusion is measured as the distance of the helical rim from the cranium; it is measured in millimeters. The specific locations where measurements are taken include the helical apex, the midpoint, and the lobe. A failure of scaphal folding (i.e., limited antihelical fold) as well as conchal hypertrophy (i.e., increased depth of the conchal wall), prominent lobules (i.e., protruding ear lobes); and anterolateral rotation of the concha (i.e., cupping of the ear) frequently create prominence of the external ear.5,13,14,30,52,57,67 Noticeable ear protrusion often results from a combination of these deformities. An accurate assessment of the ear dysmorphology is essential to the achievement of an unobtrusive look through surgery. Adjusting the scaphal (antihelical) folding with sutures, reducing the conchal wall depth via conchal excision and conchal mastoid sutures, and performing lobe set-back with sutures and excision are typical components of the surgical correction that is undertaken to achieve a favorable result.3,4,6,11,26,50,55,60,70,72 Overemphasis on the surgical creation of an antihelical fold without paying proper attention to conchal hypertrophy often results in an oversharpened antihelix and a buried helical rim (i.e., “telephone ear”). Some surgeons advocate cartilage-cutting (i.e., scoring) procedures rather than sutures to achieve a preferred antihelical fold.11 These cartilage-scoring techniques generally require dissection of the soft tissues off of the anterior surface of the cartilage. This can result in hematoma, skin necrosis, and chondritis, which may result in irreversible cartilage or external ear irregularities. Surgical correction of the outstanding ear should in general be uncomplicated and result in reliable, long-lasting, favorable aesthetics with minimal downtime for the patient and minimal chance of relapse. When considering the ideal timing for external ear surgery, it is important to balance what we know about ear and facial growth, psychosocial development, and the ability of the child to comply with the necessary routines after surgery.1,20,21,39 The goals of otoplasty for the management of congenitally prominent ears, as outlined by McDowell, remain universal despite a multitude of etiologies and suggested surgical techniques.42 According to McDowell, the surgical goals should include the following: 1. Correcting ear protrusion, by addressing the over prominent helix and antihelix 2. Achieving a smooth antihelical fold without a “sharp” crease 3. Limiting any disturbance to the postauricular sulcus Dieffenbach is credited with reporting the first otoplasty in the medical literature in 1845.15 This was performed to reconstruct a traumatically deformed ear. The ear surgery consisted of excising skin from the postauricular sulcus and suturing the conchal cartilage to the mastoid periosteum (i.e., conchal–mastoid suturing). In 1881, Ely was the first surgeon to report a procedure for the aesthetic correction of a congenitally prominent ear.19 He resected both the skin and the conchal cartilage, but he did so as a two-stage procedure (i.e., one ear at a time).56 Moristin further developed these skin-excision and cartilage-resection otoplasty techniques.44 In 1910, Luckett realized that a prominent ear frequently resulted from the congenital failure to form an antihelical fold.38 He was the first to describe setting the ear back via the removal of postauricular skin and by simultaneously completing an incision through the length of the ear cartilage in an attempt to create the deficient antihelical fold; he also placed sutures to hold the new fold in place. In 1960, Stenstrom used the known principles of cartilage biology as described by Gibson and Davis in 1958 to propose the scoring and abrading the anterior cartilage surface to weaken it and thereby create an antihelical fold.61,62,25 In 1963, Mustarde introduced the placement of mattress sutures in the posterior cartilage surface of the ear as a technique for the creation of a new antihelical fold.46–48 In 1967, Kaye combined the anterior scoring technique of Stenstrom and the posterior suture placement technique of Mustarde to limit the relapse that surgeons complained about when using either technique alone; he also advocated the use of nonresorbable suture.32 In 1968, Furnas reintroduced the technique of conchal–mastoid suturing to set back the prominent conchal bowl.22–24 He also advocated cleaning out the soft tissue in the postauricular groove (i.e., postauricular muscle and fibrofatty tissue) so that the concha could be rotated in a sagittal plane from posterior to anterior (clockwise rotation) before anchoring it to the mastoid fascia (conchal–mastoid sutures) with nonresorbable sutures. In 1969, Webster advocated paying special attention to the prominent earlobe to achieve a successful otoplasty.69 He noted that the “tail” of the helix could be repositioned with suture to change the lobe’s orientation. In 1972, Elliott combined and refined all of the previously described techniques to manage, the deep conchal wall, the limited antihelical fold, and the abnormal earlobe that were frequently seen in the prominent ear.18 He advocated the use of elliptical partial conchal wall excision when conchal–mastoid suturing alone was felt to be insufficient to correct the ear prominence. He used an anterior incision placed within the “shadow zone” of the conchal margin when conchal resection was required. Bauer advocated the use of the Elliott anterior conchal cartilage excision but preferred to also excise anterior skin to avoid postoperative skin folding or bunching.4 Embryologically, the ear arises from six hillocks of the first and second branchial arches during the second to fourth month of gestation. Hillocks 1 through 3, from the first arch, form the anteromedial aspects of the auricle (i.e., the tragus, the helical crus, and the helix, respectively). Hillocks 4 through 6, from the second arch, develop into the posterolateral aspects of the ear (i.e., the antihelix and the antitragus, respectively).34,35 During the third month of gestation, protrusion of the auricle increases. By the end of the sixth month, the helical margin curves, the antihelix forms its folds, and the antihelical crura appear at the superior aspect of the forming external ear. Congenital ear deformities result from the disruption of one or more of the auricular hillocks during embryogenesis. Any deforming forces to the side of the head of the fetus may also alter the shape of the external ear. The ear is supplied by branches from the superficial temporal artery anteriorly and the posterior auricular and occipital arteries posteriorly. The superficial temporal, posterior auricular, and retromandibular veins provide venous drainage. The lymphatic drainage of the anterior three hillocks is mainly to the anterior triangle of the neck, whereas the posterior three hillocks ultimately drain into the posterior triangle of the neck. Lastly, the ear is supplied by the great auricular nerve on its lower lateral and inferior cranial surfaces, by the lesser occipital nerve on its superior cranial surface, and by the auriculotemporal nerve on its superior lateral surface as well as the anterior superior surface of the external acoustic meatus. The Arnold nerve, which is an auricular branch of the vagus nerve, supplies the posterior inferior external auditory canal and meatus as well as the inferior conchal bowl.34,35 Bauer pointed out that the external ear may be thought of as consisting of a three-tiered cartilaginous framework with tightly adherent skin on the anterior surface and loosely applied skin on the posterior surface.4 The three tiers of sculpted cartilage form are the helical–lobular complex, the antihelical–antitragal complex, and the conchal complex. Key anatomic (aesthetic) landmarks of the normal ear include the scapha, the concha, the helix, the antihelix, the tragus, and the lobule (see Figs. 39-1 and 39-2). In a study by Farkas, two anthropometric surface measurements, ear width and ear length, were taken directly from the ears of normal subjects with the use of an anthropometric sliding caliper.20,21 At the age of 1 year, ear width is highly developed in both sexes (mean, 93.5%), and it is mostly completed at the age of 5 years (mean, 97%). The width of the ear reaches its full mature size in boys at the age of 7 years and in girls at the age of 6 years. At 1 year of age, the length of the ear has already attained 75% of its eventual adult size. By 5 years of age, 87% of its eventual development is observed. Ear length achieves its full adult size in 13-year-old boys and 12-year-old girls. Adamson and colleagues reviewed the growth patterns of the external ear and concluded that the ear reaches 85% of its overall adult size by the age of 3 years and that little change in ear width or the distance of the ear from the scalp occurs after 10 years of age.1 The authors concluded that, for all practical purposes, the normal ear is almost fully developed by the age of 6 years. Although children notice differences in each other beginning very early in life, they are rarely self-conscious about differences in ear protrusion before 5 years of age.39 From this point on, however, social interactions with peers frequently elicit negative comments that can affect self-esteem and body image. The correction of external ear deformities before this age is possible, but the postoperative course may be compromised if the ear bandage is removed early by the uncooperative child or with disruption of the repair by pulling on the ears after the bandage is removed. Consideration is given to setting back the protruding ears as early as 3 years of age, although many children display improved cooperation and parents are more confident in their decision when children are between the ages of 5 and 6 years. It is recognized that there are wide variations with regard to ear proportions, projection, and position among individuals. When feasible, the surgically reconstructed (previously protruding) ear should be of ideal size and shape and have a good relationship with the other facial features and the contralateral ear. Loose guidelines for the assessment of preferred ear shape and position have been summarized by Tolleth.67 Historically, the creation of an antihelical fold was carried out by techniques that involved either scoring or abrasion of the cartilage to control the direction and extent of folding.16,25,28 Later, suture techniques (i.e., Mustarde sutures) were added to reshape the cartilage. Many surgeons combine these methods. Interestingly, some “cartilage scorers” recommend partial-thickness scoring, whereas others score the full thickness of the cartilage.11 This author prefers to avoid scoring the cartilaginous surface all together, because this requires separation of the anterior skin from the cartilage surface with increased risk of hematoma, flap necrosis, and visible sharp edges on the anterior (cartilage) surfaces. The careful placement of Mustarde mattress sutures in a gentle curve will form a smooth antihelical fold. The Mustarde sutures are placed along the posterior surface of the cartilage as needed in the upper, middle, and lower thirds to accomplish aesthetic antihelical folding.46–48 Conchal hypertrophy is a frequent component of the ear deformity. The correction of this aspect is usually accomplished through a combination of techniques, including the following: 1) the repositioning of the concha into the surgically “cleaned out” mastoid recess; 2) conchal set-back with conchal–mastoid sutures; and 3) conchal reduction through direct elliptical cartilage excision. If the anterior approach is selected for conchal wall resection, an incision (scar) must be placed on the anterior surface, but the folding of redundant skin is limited.4 If a posterior approach is used, there is a risk that the redundant anterior skin that is left behind may not shrink sufficiently and thus result in a visible fold in the conchal floor. Some surgeons believe that a redundant anterior skin fold may be more noticeable than a “fine” anterior conchal scar. This author prefers to excise conchal cartilage with the use of a posterior approach. The anterior skin is then released from the residual conchal floor cartilage to avoid bunching, as discussed later in this chapter. Figure 39-3 Intraoperative views of postauricular skin incisions and excision as part of otoplasty. A, The location of the postauricular elliptical skin excision is demonstrated. The planned long axis of the ear excision extends from the superior helical rim to the earlobe. B, With the use of a knife (No. 15 blade), the full thickness of the skin ellipse is incised. C, With the use of blunt-tip Stevens scissors, the full thickness of the skin ellipse is removed, down to the surface of the cartilage. Figure 39-4 Intraoperative views of postauricular flap elevation and then subcutaneous tissue excision as part of otoplasty. A, Elevation of the medial postauricular flap is completed down to the mastoid fascia. B, Elevation of the lateral postauricular flap is extended to the outer edge of the helical rim. The flaps are also elevated inferiorly to the tail of the helix and superiorly to the upper aspect of helix. C, All soft tissue is cleaned out in the sulcus down to mastoid fascia (i.e., muscle and fibrofatty tissue). Figure 39-5 Intraoperative views of the creation or deepening of the preferred antihelical fold as part of the otoplasty. A, The preferred antihelical fold is located and marked on the posterior surface of cartilage with a surgical pen or methylene blue. B, The new antihelical fold is created or deepened by placing three to five carefully located horizontal mattress (Mustarde-type) sutures. The sutures are placed in a natural curve like the spokes of a wheel. Each placed Mustarde suture is tested for effectiveness with a single throw, after which it is loosened. C, After all sutures have been placed and tested, each will be carefully tied and confirmed for the preferred aesthetic effect. Note that the conchal wall excision is completed prior to placement of Mustarde stitches. Only after all of the Mustarde stitches have been secured, are the edges of the conchal walls (after elliptical excision) approximated with the use of interrupted sutures. Figure 39-6 Illustrations and patient example of the surgical correction of an antihelical fold. A, Illustration that demonstrates the removal of redundant fibromuscular tissue from the postauricular fold. B, Illustration that demonstrates the placement of a Mustarde stitch before tie down (cross section view). C, Illustration of a tied-down Mustarde stitch (cross section view). D, Intraoperative view of the anterior surface of the ear just after the placement of five Mustarde stitches that were used to create the preferred antihelical fold. Figure 39-7 Intraoperative views of conchal wall resection and reconstruction as part of otoplasty. A, The preferred antihelical fold is located on the posterior surface of the cartilage and marked with a surgical pen or methylene blue. In addition, the long axis for the planned elliptical excision of the conchal wall is located and marked on the posterior surface of the cartilage. B, The full thickness of the conchal wall ellipse for excision is incised through the cartilage with a knife (No. 15 blade) but without perforation through the anterior skin. The cartilage is then removed with the use of a Cottle elevator and Stevens scissors. This image was created after the ellipse of cartilage had been excised. C, Next, the anterior ear skin is elevated off of the residual conchal floor toward the ear canal. This is accomplished to limit bunching of the skin during the healing phase after the conchal wall edges are reapproximated with suture. D, The edges of the cut conchal wall are sutured together to limit overlap during healing. Note that it is best to suture the conchal edges together only after the Mustarde sutures are placed and tied. Figure 39-8 Illustration and patient example of deep conchal bowl correction. A, Illustration of the postauricular approach for access and then for the excision of the ellipse of the conchal wall. B, Intraoperative view after the elliptical excision of the conchal wall to “set-back” the ear. The anterior soft tissues of the ear remain intact. C and D, Clinical example of a child with a deep conchal bowl before and after surgical correction. Figure 39-9 Illustrations of a postauricular approach to the management of a prominent ear. Frequently, three rows of sutures are required for successful ear set-back. A, The illustration demonstrates the three rows of sutures being placed, but they are not yet tied down (cross section view). B, Illustration of the three rows of sutures (post auricular view) after they are tied down. The three rows of sutures include the following: 1) Mustarde (scaphoconchal) sutures; 2) conchal wall resection and then suture reconstruction of the cartilage defect; and 3) conchal–mastoid and superior helix–mastoid sutures.

Aesthetic Alteration of Prominent Ears

Evaluation and Surgery

Historic Perspective

Embryology and Anatomy

Timing of Surgery

Aesthetic Objectives

Surgical Principles

Surgical Technique (Figs. 39-3 through 39-9)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Plastic Surgery Key

Fastest Plastic Surgery & Dermatology Insight Engine