Every spring, clinicians receive a deluge of phone calls heralding the seasonal rites of passage: prom, graduation, and weddings, to name a few. The desire to look one’s best particularly during life’s milestones is human nature. It is estimated that primary care clinicians see up to 22% of patient visits that include dermatologic conditions. Therefore, it is incumbent upon the general practitioner to be well versed on the etiology and management of some of the most prevalent skin disorders, especially those which can be socially debilitating, such as acne vulgaris, rosacea, and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). In this chapter, we will explore the etiology of these common dermatoses, their potential impact on patients’ lives, and current strategies to best manage these often chronic conditions.

ACNE VULGARIS

Acne vulgaris impacts 40 to 50 million people in the United States every year at an estimated annual cost of 2.5 billion dollars. Acne is responsible for 10% of

all patient encounters and is estimated to account for 4 to 8 million visits to a health care provider each year (

Villasenor & Kroshinsky, 2011). Acne is often ascribed to the teenage population yet has been reported throughout the lifespan to include neonates and older adults. The onset of acne frequently correlates with puberty and may occur as early as 8 to 12 years of age among females during adrenarche. Males tend to develop acne somewhat later in adolescence, but develop disease of greater severity. Females tend to have a less severe, but a more chronic course. Episodes of adult-onset acne de novo seem to affect women more than men.

Because of the visible nature of the condition and the potential for permanent scarring, acne is frequently associated with psychological distress, depression, and decrease in self-esteem. The Dermatology Quality of Life Index surveys have shown that patients rank acne as comparable to the morbidity of asthma or epilepsy. Too often acne is dismissed by clinicians as a benign disease and a normal part of maturation. It can, however, have a profound psychosocial impact that has been linked with suicide in rare instances. It is important for the clinician to remain cognizant of the subtle manifestations indicating a deeper, significant psychological turmoil.

Individuals at increased risk for acne include patients with endocrine disorders such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), hyperandrogenism, Cushing syndrome, and precocious puberty. There is also a predisposition for acne among patients with at least one parent with a history of severe acne. Acne can be exacerbated by stress, hormonal fluctuations, endocrine disorders, certain medications, and diets with a high glycemic index. Medications that may trigger or worsen acne include topical and systemic corticosteroids, progesterone, testosterone, antidepressants, antiseizure medications, isoniazid, and anticancer drugs, specifically the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) drugs.

Clinical Presentation

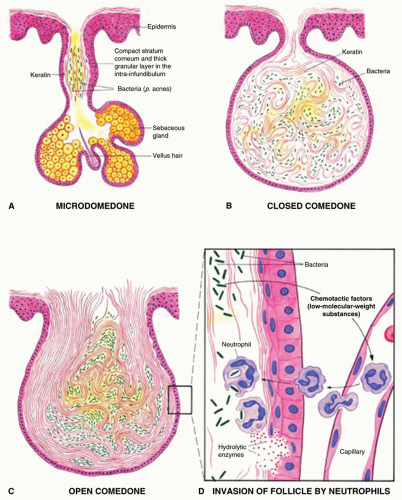

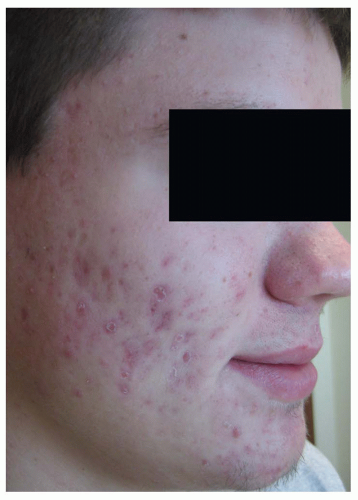

The clinical presentation of acne is varied and may assume different forms, but the initial lesion is usually an open comedo (blackhead) or a closed comedo and is clinically considered a noninflammatory lesion. The presence of comedones is required for the clinical diagnosis of acne vulgaris.

Inflammatory lesions can be observed as papules, pustules, nodules, or cysts. They are typically found on the face, chest, and back, which are often the sites of greatest concentration of pilosebaceous follicles and sebaceous activity. In addition to being described as noninflammatory or inflammatory, acne may also be classified as mild, moderate, or severe depending upon the type and number of lesions, location, and the presence or absence of scarring. Scarring is the result of prolonged inflammation and is more common with nodulocystic lesions. Additional collagen is laid down in an attempt to heal the deep tissue injury.

Figure 4-2 shows an example of atrophic scarring. Early intervention is essential to diminish the formation of scars.

A thorough history is critical when assessing the acne patient and determining a treatment regimen that will promote adherence and optimize outcomes. The many variables that must be considered are listed in

Table 4-2.

Diagnostics

Most often, acne is diagnosed clinically without the need for laboratory assistance. On occasion, the onset of acne may be an indicator of a systemic process or endocrine abnormality necessitating

additional diagnostics. DHEAS and free testosterone are good initial screening laboratory studies in evaluating hormonal influences. DHEAS is the best index of adrenal androgen activity. If there is a suspicion of precocious puberty, PCOS, or hyperandrogenism, referral to endocrinology is appropriate,

Management

When selecting a treatment approach for the patient, one must consider morphology, distribution, pathogenesis, severity, history, and patient preference. The goals of treatment are normalizing follicular keratinization, reducing sebaceous gland activity, reducing the follicular bacterial colonization, and minimizing inflammation. Treatment should be started early to prevent permanent sequelae. Ongoing maintenance therapy, particularly with a topical retinoid, is the best strategy to combat the likelihood of relapse.

The updated Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne Group (2009) recommends the first-line treatment for most patients with acne vulgaris should be topical therapy—specifically a topical retinoid plus an antimicrobial agent. This combination targets multiple pathogenic features and treats acne more effectively. As explained in

chapter 2, the vehicle chosen for topical treatment will impact the overall effect. It is important to remember that topically applied products are absorbed percutaneously through the body, therefore may be contraindicated in pregnancy—particularly retinoids (

Tables 4-3,

4-4 and

4-5).

Systemic therapy

Oral antibiotics suppress the growth of cutaneous flora such as

P. acne and also have an anti-inflammatory effect. They are generally indicated when there is widespread involvement of face, chest, and back or if there is cystic involvement of the face. Long-term use is not recommended; however, at least a 3-month trial must be given before improvement will be seen (

Table 4-6).

Hormones

Hormonal therapy may be necessary when the pathogenesis of a patient’s acne is heavily influenced by sebum production. Consideration for hormonal therapy must be made on an individual patient bases. And since many of these patients are young adult females, education and counseling for the patients and their parents are very important.

Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) are used in acne to suppress testosterone production. This can be especially effective in conditions such as PCOS and can reduce the occurrence of acne and excess facial hair. OCPs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acne include Ortho Tri-Cyclen (estrogen and norgestimate), Estrostep (estrogen and norethindrone), and Yaz (estrogen and drospirenone).

Patients considering oral contraceptive therapy should be cautioned that the FDA has concluded that birth control pills containing drospirenone may have increased risk for blood clots compared to pills containing other progestins. Patients should be assessed for contraindications and risk factors prior to starting therapy. Other forms of contraception, such as Depo Provera injection or the intrauterine device (IUD) known as Mirena, have been shown to worsen acne, although they are excellent mechanisms for pregnancy prevention.