(1)

Hôpital Universitaire de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France

Abstract

Some diseases cause abnormalities in the thickness and/or consistency of the skin. These need to be assessed by pinching and stretching the skin. The skin may become too hard and lose its usual suppleness or on the contrary may be too supple. These abnormalities result from pathological or physiological modifications (aging) of its connective tissue, the dermis, which is composed mostly of collagen bundles and elastic fibers.

Some diseases cause abnormalities in the thickness and/or consistency of the skin. These need to be assessed by pinching and stretching the skin. The skin may become too hard and lose its usual suppleness or on the contrary may be too supple. These abnormalities result from pathological or physiological modifications (aging) of its connective tissue, the dermis, which is composed mostly of collagen bundles and elastic fibers.

6.1 Sclerosis

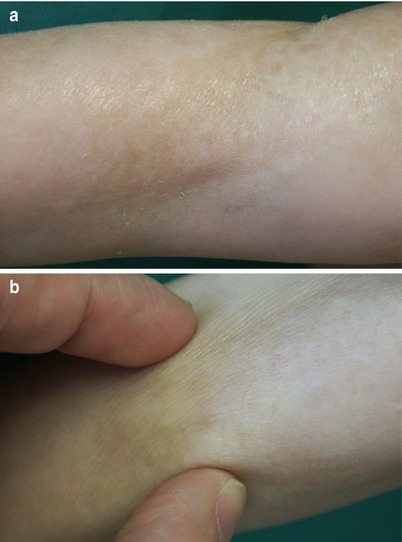

Sclerosis is an induration or hardening of the skin, which has lost its normal suppleness. The skin can no longer be pinched (Fig. 6.1b). This condition is often associated with a pigment disorder as the skin becomes hyper- and/or hypopigmented in sclerotic areas (Fig. 6.1a, b).

Fig. 6.1

Cutaneous sclerosis. Morphea. The skin has lost its suppleness and can no longer be folded between the thumb and index finger (b). Dyschromia is present, with hyper- and hypopigmented areas (a, b). Also note the skin’s shiny and finely wrinkled appearance

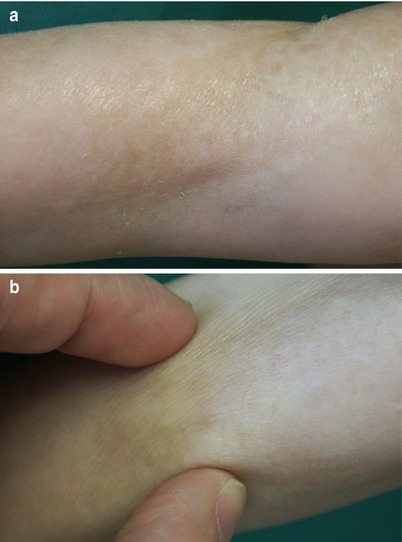

6.2 Skin Hyperextensibility

Skin that can abnormally be extended, but maintains normal elasticity by returning to its initial position after extension, is called hyperextensible (Fig. 6.2a). Skin hyperextensibility reflects an abnormality of the dermal collagen. It is often associated with joint hypermobility (Fig. 6.2b).

Fig. 6.2

Cutaneous (a) and articular (b) hyperextensibility. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. The skin can be abnormally stretched but immediately returns to its initial position when released. This syndrome includes numerous genetic variants with different clinical pictures and is related to an anomaly of the connective tissue. Skin elasticity remains normal since the skin returns to its initial position when pulled. This hyperextensibility is also observed in Marfan syndrome

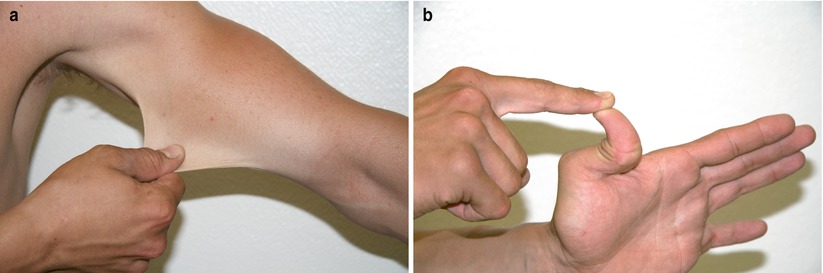

6.3 Loss of Elasticity

Alteration or loss of elastic tissue results in loss of skin elasticity. The skin subsequently becomes loose and does not recover its initial aspect after pinching; imprinted marks persist. There is spontaneous formation of wrinkles, lines, and skin folds (Fig. 6.3) and/or of an actual cutis laxa which refers to loosening of the skin which hangs and does not recover after extension (Fig. 6.4). Thus, loss of elasticity results in permanent skin folds located in areas where the skin is not usually being repeatedly folded.

Fig. 6.3

Loss of elasticity. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Functional alteration of elastic fibers causes loss of elasticity. In this patient, it results into the formation of permanent folds in the axillae, with the appearance of “hanging skin”

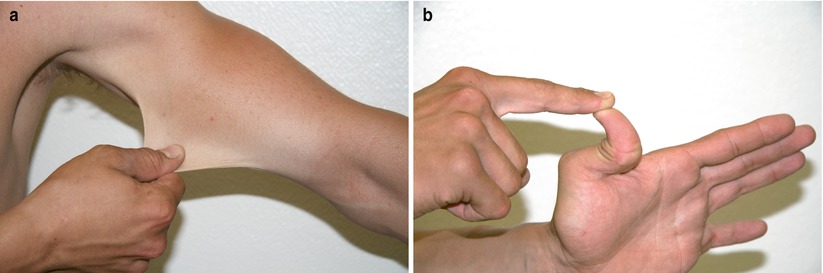

Fig. 6.4

Abnormally folded skin, skin atrophy and “peau d’orange” (orange peel) appearance. Cutis laxa. Cutis laxa results in loss of elasticity of the skin caused by the destruction of elastic fibers. It can be genetically determined or can be acquired as in this young woman, where it occurred secondary to cutaneous mastocytosis. Note the finely wrinkled skin in the lumbar area, as well as bigger folds on the sides. Finally, due to the complete disappearance of the elastic fiber network in the skin of this young woman, including in the peripilar adventitial dermis, hair follicles become prominent and confer this peau d’orange (orange peel) appearance

6.4 Atrophy

Atrophy of the skin corresponds the reduction or loss of some or all skin components (epidermis, dermis, hypodermis, or two to three skin compartments). Epidermal or dermo-epidermal atrophy manifests as thinning of the skin and wrinkling upon superficial pinching. The skin loses its (micro)-relief and elasticity and takes a shiny, smooth, translucent, and pearly appearance (cf. Figs. 2.4 and 3.16). Dermal vessels become abnormally visible through the skin’s transparent layers, due to thinning (Fig. 6.5).