60. Abdominoplasty

Wesley N. Sivak, Luis M. Rios, Jr., James Christian Grotting

ANATOMY

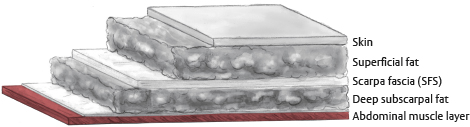

■ The abdominal wall is composed of seven layers.

1. Skin

2. Subcutaneous fat

3. Scarpa fascia (the superficial fascial system of the abdomen)

4. Subscarpal fat

5. Anterior rectus sheath

6. Muscle

7. Posterior rectus sheath

SKIN

■ The skin of the abdominal wall receives a rich vascular supply from multiple muscle and fascial perforating vessels.

■ The skin of the abdominal wall can vary in quality depending on a person’s genetics, age, previous pregnancies, and history of weight gain and loss.

■ The skin of the abdominal wall may feature multiple striae, which are evidence of attenuated or absent dermis.

FAT

■ The abdominal wall has two layers of fat, superficial and deep, separated by Scarpa fascia (Fig. 60-1).

Fig. 60-1 Layers of fat. (SFS, Superficial fascial system.)

• The superficial layer of fat is thicker, more dense, more durable, and has a heartier blood supply.

• The deeper layer of fat is less dense and receives most of its blood from the subdermal plexus and underlying myocutaneous perforators.

SENIOR AUTHOR TIP: Because the blood supply to the deeper fat is distinct from the blood supply to the skin, it can be more easily excised when thinning the abdominal wall flap in an abdominoplasty. By contrast, thinning the superficial layer of fat may lead to vascular compromise of the overlying skin.

■ There are four paired muscle groups of the abdominal wall.

1. Rectus abdominis

2. External oblique

3. Internal oblique

4. Transversus abdominis

■ The aponeurotic portions of the transversus muscle and the two oblique muscles envelop the rectus abdominis muscles, forming the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths and meeting in the midline to form the linea alba.

■ The arcuate line represents a transition point.

• Above the arcuate line, there are distinct anterior and posterior rectus sheaths.

• Below the arcuate line, contributions from the internal oblique and transversus abdominus join contributions from the external and internal obliques to form a single anterior rectus sheath with no posterior rectus sheath.

• The arcuate line is roughly halfway between the umbilicus and symphysis pubis.

VASCULARITY OF THE ABDOMINAL WALL

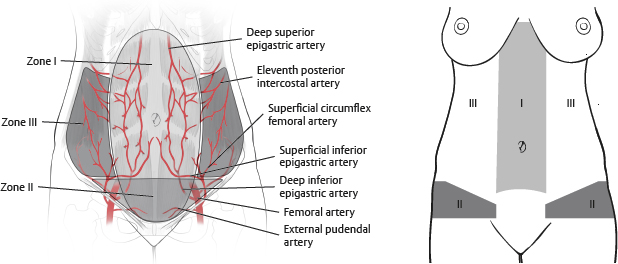

■ Huger1 divided the vascular supply to the abdominal wall into three zones (Fig. 60-2).

Fig. 60-2 Huger vascular zones.

• Zone I

► Between the lateral borders of the rectus sheath from the costal margin to a horizontal line drawn between the two anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS)

► Supplied primarily by superficial branches of the superior and inferior epigastric systems

• Zone II

► Below the horizontal line between the two ASISs to the pubic and inguinal creases

► Supplied by the superficial branches of the circumflex iliac and external pudendal vessels

• Zone III

► Superior to zone II and lateral to zone I

► Supplied by intercostals, subcostals, and lumbar vessels

■ Sensation to the abdomen is from intercostal nerves T7-12.

NERVES AND THE ABDOMINAL WALL

LATERAL CUTANEOUS BRANCHES

■ Perforate the intercostal muscles at the midaxillary line

■ Travel within the subcutaneous plane

ANTERIOR CUTANEOUS BRANCHES

■ Travel between the transversus abdominus and internal oblique muscles to penetrate the posterior rectus sheath just lateral to the rectus

■ Eventually enter the rectus muscles and then pass to the overlying fascia and skin

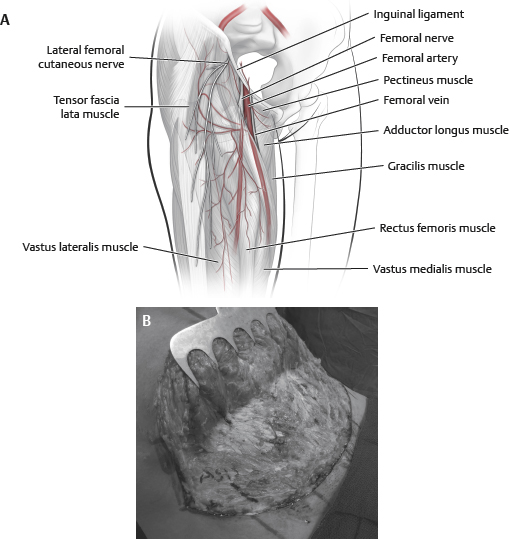

LATERAL FEMORAL CUTANEOUS NERVE (Fig. 60-3)

Fig. 60-3 Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. A, Diagram of the nerve anatomy. B, Location of the ASIS in relation to the umbilicus.

■ Innervates the skin in the lateral aspect of the thigh

■ Emerges close to the ASIS

■ The umbilicus is located on or near the midline at the level of the iliac crest.

• The umbilicus is located exactly in the midline of the body in only 1.7% of patients.2

• An aesthetically pleasing umbilicus has the following characteristics3:

► Superior hooding

► Inferior retraction

► Round or ellipsoid shape

► Shallow

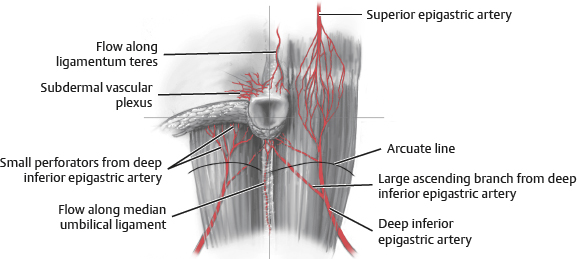

• Blood supply to the umbilicus (Fig. 60-4) is from:

Fig. 60-4 Blood supply to the umbilicus.

► Subdermal plexus

► Right and left deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA)

► Ligamentum teres

► Median umbilical ligament

AESTHETIC ASPECTS OF ABDOMINOPLASTY4

■ Incision should be low and symmetrical

■ Umbilicus

• Inverted scar

• Superior hooding

• Circular or ellipsoid

■ Scaphoid abdominal wall

■ Smooth transition at the incision

■ Aesthetic appearance of mons pubis

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

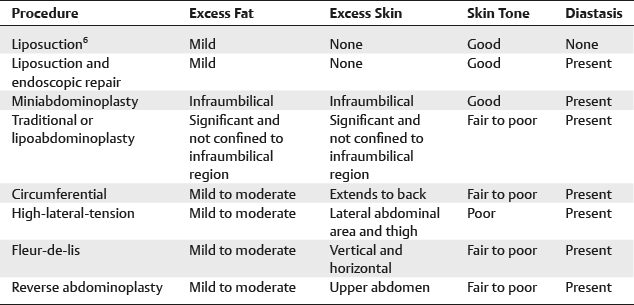

■ Due to the number of variations of the abdominoplasty procedure, it is key to select the appropriate technique for each patient to minimize morbidity and deliver the intended result (Table 60-1).5 Selection of appropriate technique is based on the patient’s expectations and physical examination.

Table 60-1 Indications

CONTRAINDICATIONS

■ Absolute

• Significant health risks, unrealistic surgical goals, and body dysmorphic disorder are primary contraindications for an abdominoplasty.

■ Relative

• Right, left, or bilateral upper abdominal scars

• Severe comorbid conditions (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, morbid obesity [BMI >40], cigarette smoking)

• Plans for future pregnancy

• A history of thromboembolic disease

• Subcostal scars are particularly concerning, and many of these patients are not optimal candidates for a traditional abdominoplasty.

► These scars represent an interruption in the blood supply upon which the abdominoplasty flap will rely postoperatively.

■ Patients with a disposition to keloid formation or hypertrophic scars have to be accepting of the poor scarring associated with these conditions.

■ Gross deformity in adjoining areas may lead to disfiguring results and poor patient satisfaction.

• Most massive-weight-loss patients are not candidates for abdominoplasty alone and will require circumferential procedures.

■ Increased intraabdominal pressures can lead to serious problems postoperatively, possibly resulting in abdominal compartment syndrome.

• In cases of elevated intraabdominal pressure, the abdominal wall elevates above a line between the costal margin and iliac crest in the supine position.

• Abdominoplasty procedures with or without rectus plication have to be performed cautiously in the nonscaphoid abdomen.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

■ Assessment must include a detailed medical history with specific focus on:

• Prior cesarean section or other abdominal surgeries

• Pregnancy history

• Weight fluctuations and stability

• Prior liposuction in the abdominal area

• Thromboembolic risk

• Smoking status

• Hormone use

• History of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV)

TIP: Abdominoplasty is an enormous stressor in terms of blood supply to the abdominal wall. To minimize complications, avoid operating on active smokers. If a patient has a history of smoking, insist that the patient quit smoking prior to the procedure. A thorough discussion of the increased risk of complications associated with smoking must occur. In certain cases, a urine nicotine test may be warranted preoperatively and postoperatively should complications occur.

■ Other patient factors to consider include:

• Weight fluctuations and constancy

• Exercise routine

• Gastrointestinal history including irritable bowel syndrome or constipation

• Cardiac and pulmonary history (including obstructive sleep apnea)

• Desire for future pregnancy (patients should be encouraged to wait)

■ Physical examination must explore the existence and localization of vertical and horizontal abdominal tissue excess and its relation to the underlying abdominal wall; deformity present in adjoining areas must be noted as they affect the final result.

TIP: If the patient is examined only in the standing or supine positions, one may be fooled into thinking there is little to no excess skin. The patient must be examined while standing, sitting, and supine.

■ Musculofascial laxity must be thoroughly assessed (Fig. 60-5).

Fig. 60-5 The classic “diver’s test” demonstrating the extent of abdominal wall laxity.

• A diver’s test can be performed with the patient first standing and flexing at the waist; worsening of lower abdominal fullness indicates significant laxity (see Fig. 60-5).

• The pinch test can also be performed. If tensing the abdominal wall significantly decreases the amount of fullness, significant laxity is present.

• Midline rectus diastasis must be assessed by palpation of a tensed abdominal wall in the supine position.

TIP: Nearly all patients who have been pregnant have some degree of musculofascial laxity of the abdominal wall in addition to excess skin.

TIP: The importance of a thorough hernia examination cannot be overstated. Preoperative knowledge of hernias can help the surgeon avoid bowel injury during dissection. Depending on the site of the hernia and the comfort level of the plastic surgeon, preoperative knowledge of a hernia may allow repair to be coordinated with a general surgeon. In cases of uncertainty, a computed tomography (CT) scan is indicated.

• The presence of scars represents alterations to the blood supply of the abdominal wall and must be thoroughly assessed.

► Upper midline scars may limit the inferior movement of the abdominal skin flap; they may require release at the time of abdominoplasty.

► Subcostal scars represent an interruption of the superolateral blood supply that the abdominoplasty flap relies upon postoperatively (these patient are at highest risk of complications).

CAUTION: To prevent wound-healing complications, the abdominal wall skin flap must not be undermined beneath a subcostal incision. The limitations of undermining, limited results, and high risk of complications must be discussed with these patients. Many are not candidates for abdominoplasty.

• Examine for rashes or excoriations on the abdominal wall, especially under the pannus in obese and massive-weight-loss patients.

• Photographic documentation consisting of eight views should be obtained preoperatively and postoperatively: anterior, oblique anterior, side, oblique posterior, posterior, anterior sitting position, bending position (both front and side views) (see Chapter 3).

► Views with the patient’s abdominal wall contracted and relaxed may also prove beneficial in surgical planning.

► Views with the patient grasping and holding up excess abdominal tissue in the central and waist areas may also prove useful.

INFORMED CONSENT

■ In addition to the standard risks of surgery, the surgeon must discuss the location and length of scars with the patient. Considerations include:

• Standard lower abdominal transverse scar

• Standard circumumbilical scar

• Potential need for a midline vertical scar

• Potential for cutaneous deformities or “dog-ears” at the lateral ends of the abdominoplasty incision

■ Abdominal striae located inferior to the umbilicus may be removed as part of the abdominoplasty. Above the umbilicus, striae will not be removed and may become more prominent as a result of abdominoplasty.

■ Wound-healing complications must be discussed as both the transverse incision at the waist and the umbilicus are at risk due to the blood supply to these regions following the abdominoplasty procedure.

■ Loss or malposition of the umbilicus must be discussed; patient should be reminded that the structure is truly midline in only 1.7% of patients.2,7

■ Risk of postoperative seroma formation should be discussed; the need and purpose for postoperative drains should be thoroughly explained (if used).

■ Comprehensive postoperative care instructions should be fully discussed. The use of any additional recommended materials such as compression garments or specialized dressings and the associated costs should be fully disclosed.

■ Potential need for secondary revision surgeries or additional procedures must be discussed.

TIP: Most patients requesting abdominoplasty have at least some degree of fat excess in the hips, flanks, or thighs. These areas will become more noticeable postoperatively. The patient should be made aware of this and should be encouraged to consider concomitant or staged liposuction procedures. Failure to disclose this preoperatively will result in an unhappy patient with a less than optimal result.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree