Chapter 20 Abdominoplasty

Summary

Introduction

The modern history of abdominal contouring began in 1899 with Kelly1,2 performing an abdominal apronectomy or dermolipectomy to eliminate a large abdominal pannus. In 1957, Vernon3 described umbilicus transposition. Gonzalez-Ulloa4 in 1959 popularized the abdominoplasty technique describe by Somalo5 in 1946 where he resected a circular skin pattern from the lower abdominal region extending around the waist in a belt lipectomy fashion. In 1967, Pitanguy6 presented his technique consisting of inconspicuous scars in the lower abdomen and groin, wide superior dissection up to the costal margins and xiphoid, plication of the transverse abdominal rectus muscle and umbilicoplasty. Regnault,7 in 1972, introduced the concept of abdominoplasty in a ‘W’ pattern, and in subsequent years described modifications of the technique including a fleur-de-lis and modified belt lipectomy. Grazer,8 in 1973, reported 44 cases of abdominoplasty hiding the incision in the bikini line. The concept of miniabdominoplasty was introduced by Elbaz and Flageul9 in 1971, and later modified by Glicenstein10 in 1975. The introduction of liposuction in the late 70s added a significant tool to abdominoplasty and body contouring in general.11 Matarasso,12,13 in the late 80s, made a significant contribution by introducing his classification scheme and by describing the incorporation of liposuction with modified abdominoplasty procedures. Lockwood,14 in 1991, described a new concept – the superficial fascial system (SFS), which is a highly organized collagen structure responsible for anchoring the skin of the body and for supporting the weight of the fat throughout life. In 1995 he introduced a high lateral tension abdominoplasty (HLTA), which was designed to create more lateral abdominal improvement and anterior thigh elevation.15 Within the past decade Saldanha16 introduced and popularized ‘lipoabdominoplasty’, which has become fairly popular in South America and Europe. It is a technique that utilizes extensive liposuction of the entire abdomen combined with minimal undermining in the hope of reducing the risks of tissue necrosis and seroma formation.

Indications

Patients seeking abdominoplasty most often complain of excess skin and subcutaneous tissue in the abdomen and abdominal protrusion due to laxity of abdominal wall caused by previous pregnancy, weight fluctuations and/or aging. Many of these patients will present with lipodystrophy of the hips and lateral thighs as well.17 A traditional abdominoplasty is indicated when the deformities involve both the supra and infraumbilical regions whereas a mini-abdominoplasty is usually indicated if the problems are limited to the infraumbilical region. Although most patients are female, males do present with similar problems, but often complain of adiposity in the flank areas and supraumbilical rectus diastasis.18–20

Smoking has been implicated in occlusive microvascular thrombosis and delayed wound healing and when associated with a procedure that already compromises the blood supply of the abdominal skin flap, can result in tissue necrosis and jeopardize the outcome. Active smokers are excluded by most surgeons, but some surgeons are willing to operate on them utilizing techniques that reduce abdominal flap elevation to reduce the risk of vascular compromise.21–23

Previous abdominal scars

Mini-abdominoplasty

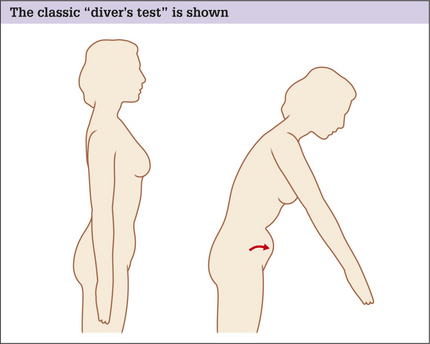

Indications for mini-abdominoplasty are limited to patients who present with abdominal laxity restricted to the infraumbilical region.24 The laxity has to be minimal and may be of the abdominal wall and/ or of the skin/fat envelope. Physical examination of the abdomen in the supine position will demonstrate infraumbilical rectus diastasis, which can be confirmed by the ‘diver’s test’ (see Fig. 20.1). These patients are usually young women who have had one or two pregnancies, have good skin elasticity, and are not overweight. Mini-abdominoplasty, with any of its modifications, is not a procedure that is often employed because it is the unusual patient that will fit its required criteria.

High lateral tension abdominoplasty

An HLTA15,25 is fundamentally different from the traditional abdominoplasty in the following ways:

Lipoabdominoplasty

Lipoabdominoplasty was introduced and popularized by Saldanha16 from Brazil. This technique, with a variety of its forms, is becoming more popular around the world especially in South America and Europe. For the surgeons who espouse lipoabdominoplasty, it is an alternative technique that accomplishes many of the same goals as traditional abdominoplasty but maybe safer and associated with less complications (Box 20.1). Currently many American plastic surgeons are starting to utilize the technique in its entirety or at least in some of its main aspects. Lipoabdominoplasty has some similarities to HLTA.

Box 20.1 Theoretical advantages of lipoabdominoplasty

Preoperative Considerations

Physical examination

Skin

The overall quality of skin, including scars and stretch marks should be noted. The skin should be examined to determine its vertical excess and the extent of its laxity in the different regions of the abdomen. Often multiparous women present with stretch marks that involve the infra and supraumbilical regions.26 The patient needs to understand that infraumbilical skin will most often be removed, but supraumbilical stretch marks will not. These remaining stretch marks are often less unattractive when stretched by the procedure and can be hidden by some bikini patterns because of their transference to the lower abdomen.

Subcutaneous fat

A protruding abdomen may be caused by a number of factors, alone or in combination.

Abdominal wall laxity

A third reason for a protruding abdomen is abdominal wall laxity. It is essential to ascertain the integrity of the abdominal wall, whether there are any hernias present, and the extent of intra-abdominal or visceral fat. The exam is fairly easy in thin patients, but can be more cumbersome and difficult in the overweight or obese patient.

A number of tests can be performed, which alone or in combination, can give the examiner a feel for the degree and extent of any laxity. Initially the patient is asked to stand and relax their abdominal wall completely. For many this is not easy and they must be coaxed into cooperating. An appreciable amount of abdominal protrusion in this position usually indicates significant abdominal wall laxity. To confirm the result of this simple test, the patient is asked to perform the classic ‘diver’s test’ (Fig. 20.1).

Operative Approach

Relevant anatomy

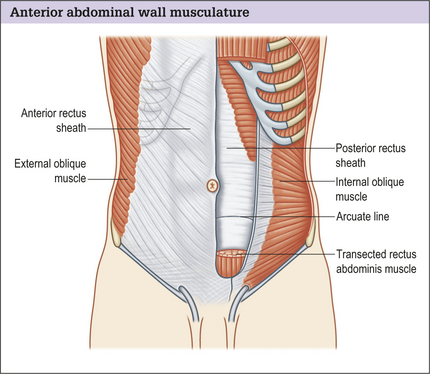

The anterior abdominal muscle wall may be considered to have two parts:

The rectus muscle is enclosed in a stout sheath formed by a bilaminar aponeurosis, which passes anteriorly and posteriorly around the muscle, decussating in the midline to form the linea alba. Anteriorly the sheath is made up of the external oblique fascia and the anterior portion of internal oblique fascia. Posteriorly the sheath is made of the posterior portion of the internal oblique fascia and the transversus abdominis muscle fascia. Halfway between the umbilicus and the pubis, the posterior sheath layers pass anteriorly at the arcuate line of Douglas. The lack of support below the line of Douglas leads to a natural tendency toward lower abdominal fullness.

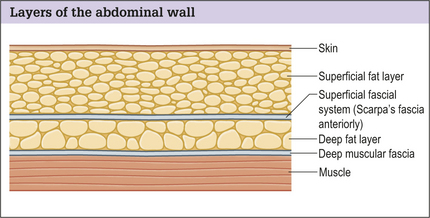

Subcutaneous abdominal fat is compartmentalized into superficial and deep layers divided by the superficial fascial system, which in this region of the body is called Scarpa’s fascia. In patients who are relatively thin, the two layers of fat are fairly close to each other in thickness. In patients who have a large BMI the superficial fat layer is often much thicker than the deep layer (Fig. 20.3). The superficial fat layer is compact, dense with fat cells contained within well organized fibrous septa, whereas the deep fat is a loose areolar layer.

Vascular zones

Regardless of the technique used when performing abdominoplasty, vascular territories are interrupted and should be taken into account especially when upper abdominal scars are present.27 Thus a thorough knowledge of the blood supply of the abdominal skin and fat is essential. Huger28 studied the blood supply to the abdomen and designated three vascular zones (Fig. 20.4):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree