Benign Neoplasms and Hyperplasias

Disorders of Melanocytes

Epidemiology and Etiology

One of the most common acquired new growths in Caucasians (most adults have about 20 nevi), less common in blacks or pigmented persons, and sometimes absent in persons with red hair and marked freckling (skin phototype I).

Race. Blacks and Asians have more nevi on the palms, soles, and nail beds.

Heredity. Common acquired NMN occur in family clusters. Dysplastic melanocytic nevi (DN) (see Section 12), which are putative precursor lesions of malignant melanoma, are different from NMN and occur in virtually every patient with familial cutaneous melanoma and in 30–50% of patients with sporadic nonfamilial primary melanoma.

Sun Exposure. A factor in the induction of nevi on the exposed areas.

Significance. Risk of melanoma is related to the numbers of NMN and to DN. In the latter, even if only a few lesions are present.

Clinical Manifestation

Duration and Evolution of Lesions. NMN appear in early childhood and reach a maximum in young adulthood even though some NMN may arise in adulthood. Later on there is a gradual involution and fibrosis of lesions, and most disappear after the age of 60. In contrast, DN continue to appear throughout life and are believed not to involute (see Section 12).

Skin Symptoms. NMN are asymptomatic. However, NMN grow and growth is often accompanied by itching. Itching per se is not a sign of malignancy, but if a lesion persistently itches or is tender, it should be followed carefully or excised, since persistent pruritus may be an early indication of malignant change.

Classification

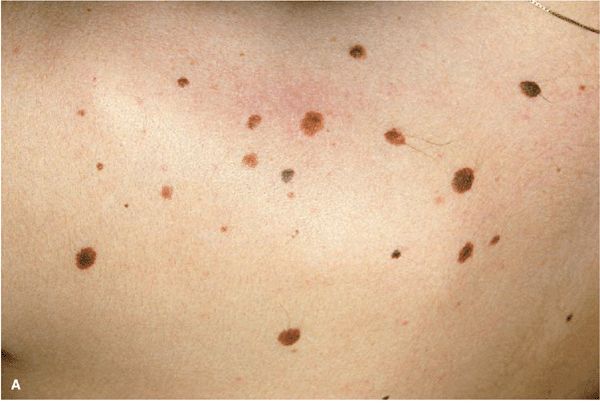

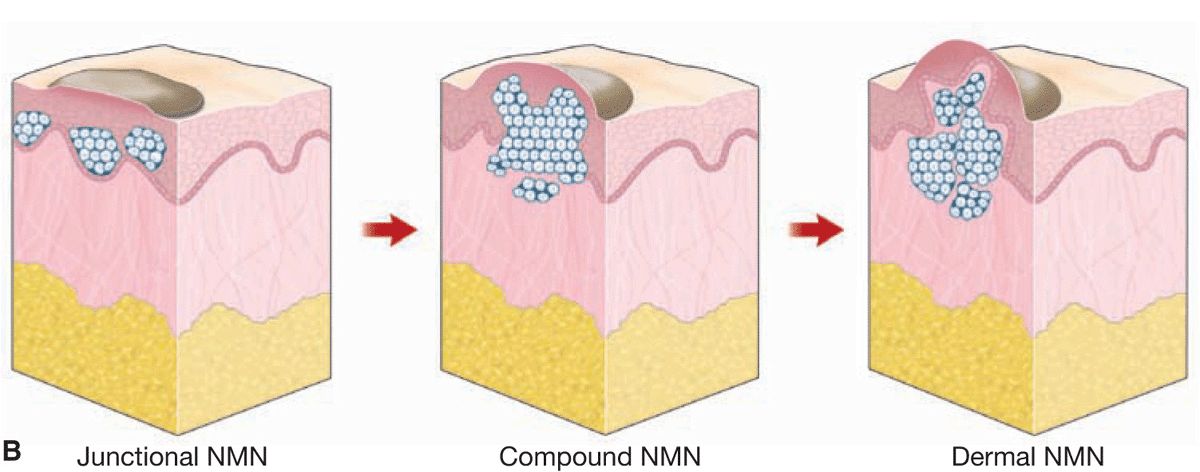

NMN are multiple (Fig. 9-1A) and can be classified according to their state of evolution and thus according to the histologic level of the nevus cell clusters (Fig. 9-1B).

Figure 9-1. (A) Multiple NMN on the shoulder of a 32-year-old female. Most of these nevi are junctional NMN; some are slightly elevated and thus compound NMN. Note relatively uniform shape and color of the lesions. Because of different developmental stages, they are of varying size ranging from 1 to 4 mm in diameter and they are regular and have a relatively uniform shape. (B) Junctional NMN arise at dermal–epidermal junction and are intraepidermal, pigmented, and flat. In compound NMN, nevus cells have invaded the dermis and are thus both intraepidermal and dermal. Since, as a rule, only junctional nevus cells have the capacity to form melanin, they are still pigmented, but since they continue to grow, they are more elevated than junctional NMN. In dermal NMN, all nevus cells are now in the dermis and have lost the capacity to produce melanin. Dermal NMN are thus skin-colored, pink, or only slightly tan. As they still grow and expand into the dermis, they lift the lesion upward and are thus usually dome-shaped or papillomatous.

1. Junctional melanocytic NMN: These arise at the dermal–epidermal junction, on the epidermal side of the basement membrane; in other words, they are intraepidermal (Figs. 9-1B and 9-2).

2. Compound NMN: Nevus cells invade the papillary dermis, and nevus cell nests are now found both intraepidermally and dermally (Figs. 9-1B and 9-3).

3. Dermal melanocytic NMN: These represent the last stage of the evolution of NMN. “Dropping off” into the dermis is now completed, and the nevus grows or remains intradermal (Figs. 9-1B and 9-4). With progressive age, there will be gradual fibrosis (Fig. 9-4C).

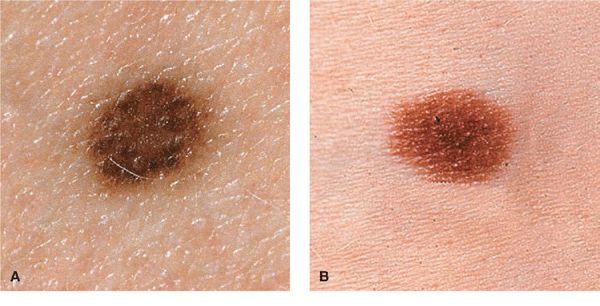

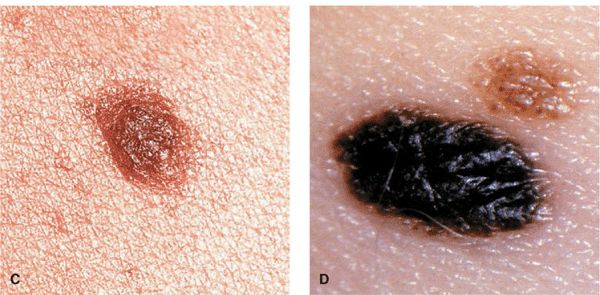

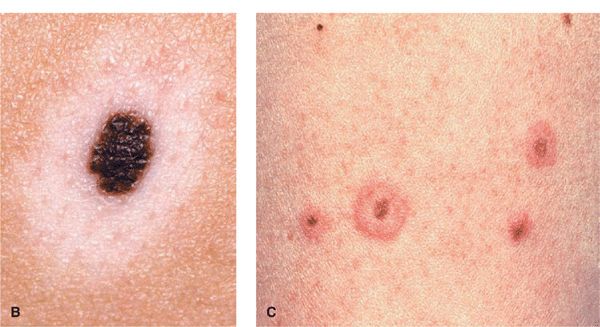

Figure 9-2. (A-D) Junctional NMN Lesions are completely flat (A, B) or minimally elevated as in (C) and (D). They are symmetric with a regular border and, depending on the skin type of the individuals, have different shades of brown to black (D).

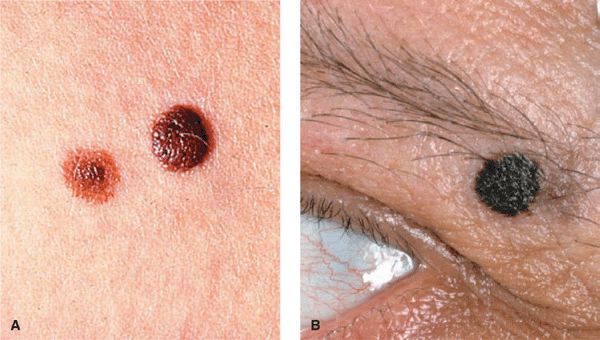

Figure 9-3. Compound NMN Uniformly pigmented papules and small domed nodules. (A) The lesion to the left is flatter and tan with a more elevated darker center; the larger lesion (on the right) is older and chocolate-brown; the left lesion is younger and has a predominantly junctional component at the periphery. (B) A heavily pigmented dome-shaped lesion in the eyebrow. It is sharply defined, uniformly black, smooth and slightly cobblestone-like surface, and sharply and regularly defined. It measures less than 5 mm.

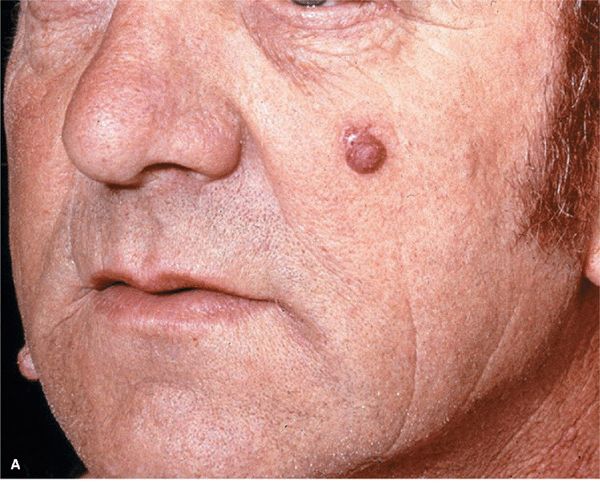

Figure 9-4. Dermal melanocytic NMN (A) Two dome-shaped, sharply defined relatively soft tan nodules on the left cheek and right lateral mandibular region in a 60-year-old male. These lesions were previously much darker and less elevated. (B) A larger magnification of a dermal NMN. This lesion is sharply defined, has a reddish color with a central regular pigmented spot where the nevus obviously is still compound in nature. (C) Old dermal nevus on the upper lip of a 65-year-old woman. This lesion is relatively hard, has a smooth surface, and a pinkish color. This lesion is fibrosing.

Thus, melanocytic NMN undergo the evolution from junctional → compound → dermal NMN (Fig. 9-1B). Since the capacity of NMN cells to form melanin is greatest when they are located at the dermal–epidermal junction (intraepidermally) and since NMN cells lose their capacity for melanization, the further they penetrate into the dermis, the lesser is the intensity of pigmentation with the increase in the dermal proportion of the nevus. Purely dermal NMN are therefore almost always without pigment. In a simplified manner, the clinical appearance of NMN along this evolutionary path can be characterized as follows: junctional NMN is flat and dark, compound NMN is raised and dark, and dermal NMN is raised and light. This evolution also reflects the age at which the different types of NMN are found. Junctional and compound NMN are usually seen in childhood and through the teens, whereas dermal NMN start manifesting in the third and fourth decade.

Junctional Melanocytic Nevocellular Nevi

Lesions. Macule, or only very slightly raised (Fig. 9-2). Uniform tan, brown, dark brown, or even black. Round or oval with smooth, regular borders. Scattered discrete lesions. Never >1 cm in diameter; if >1 cm, the “mole” is a congenital nevomelanocytic nevus, a DN, or a melanoma (see Section 12).

Compound Melanocytic Nevocellular Nevi

Lesions. Papules or small nodules (Fig. 9-3). Dark brown, sometimes even black; dome-shaped, smooth or cobblestone-like surface, regular and sharply defined border, sometimes papillomatous or hyperkeratotic. Never >1 cm in diameter; if >1 cm, the mole is a congenital nevomelanocytic nevus, a DN, and a melanoma. Consistency either firm or soft. Color may become mottled as progressive conversion into dermal NMN occurs. May have hairs.

Dermal Melanocytic Nevocellular Nevi

Lesions. Sharply defined papule or nodule. Skin-colored, tan or flecks of brown, often with telangiectasia. Round, dome-shaped (Fig. 9-4), smooth surface, diameter <1 cm. Usually not present before the second or third decade. Older lesions, mostly on the trunk, may become pedunculated and do not disappear spontaneously. May be hairy.

Distribution. Face, trunk, extremities, scalp. Random. Occasionally palmar and plantar, in which case these NMN usually have the appearance of junctional NMN.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis. Made clinically. As for all pigmented lesions, the ABCDE rule applies (see Section 12). In case of doubt, apply dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy), and if malignancy cannot be excluded even by this procedure, excise lesions with a narrow margin.

Differential Diagnosis. Junctional NMN: all flat, deeply pigmented lesions. Solar lentigo, flat atypical nevus, and lentigo maligna. Compound NMN: all raised pigmented lesions. Seborrheic keratosis, DN, small superficial spreading melanoma, early nodular melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), dermatofibroma, Spitz nevus, and blue nevus. Dermal NMN: all light tan or skin-colored papules. BCC, neurofibroma, trichoepithelioma, dermatofibroma, and sebaceous hyperplasia.

Management

Indications for removal of acquired melanocytic NMN are the following:

Site: Lesions on the scalp (only if difficult to follow and not a classic dermal NMN); mucous membranes, anogenital area.

Growth: If there is rapid change in size.

Color: If color becomes variegated.

Border: If irregular borders are present or develop.

Erosions: If lesion becomes eroded without major trauma.

Symptoms: If lesion begins to persistently itch, hurt, or bleed.

Dermoscopy: If criteria for melanoma or a dysplastic nevus are present or appear de novo.

Melanocytic NMN never become malignant because of manipulation or trauma. In those cases where this was claimed, the lesion was initially a misdiagnosed melanoma. If there is an indication for the removal of an NMN, the nevus should always be excised for histologic diagnosis and for definite treatment (particularly applicable to and decisive in ruling out congenital, dysplastic, or blue nevi). Removal of papillomatous, compound, or dermal NMN for cosmetic reasons by electrocautery requires that a nevus be unequivocally diagnosed as benign NMN and histology be performed. If an early melanoma cannot be excluded with certainty, an excision for histologic examination is obligatory but can be performed with narrow margins.

Figure 9-5. (A) Halo melanocytic NMN on the back of a 22-year-old female There are five halo nevi, all with a pigmented dot-like central junctional or compound NMN surrounded by a hypo- or amelanotic halo. The arrow indicates one lesion where the central nevus has completely regressed; the reddish color indicates telangiectasia. (B) Larger magnification of a halo NMN. The nevus is a junctional NMN (compare with Fig. 9-2) that is surrounded by a hypomelanotic (almost white) halo. (C) Several tan junctional NMN that are surrounded by an erythematous halo. This is the early stage of halo development. The erythematous rim will later be replaced turn white.

Figure 9-6. Blue nevus There are four tan junctional NMN and one bluish-black round lesion on the cheek of a 17-year-old girl. In contrast to the junctional NMN, the blue nevus is palpable with a relatively high consistency, and upon dermoscopy will appear as an ill-defined uniformly bluish lesion deep in the dermis.

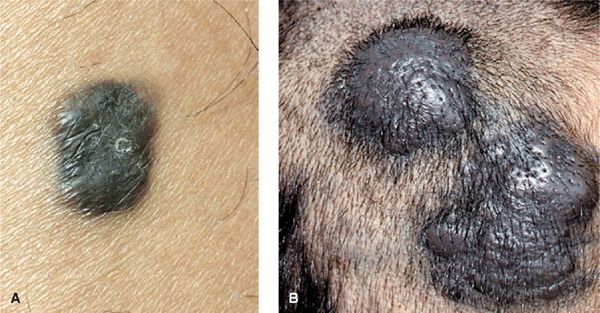

Figure 9-7. Blue nevus and cellular blue nevus (A) This blue nevus has regular borders but is not circular and is solidly blue-black in color. The epidermis is smooth, indicating that the lesion is in the dermis. The consistency is increased and the margins are well defined. Differential diagnosis must include nodular melanoma. (B) This cellular blue nevus appeared as two large, bluish-black nodules on the scalp. After excision, histology showed that they were contiguous and thus represented one single lesion. Cellular blue nevi are much larger and should always be excised to rule out melanoma, which, albeit rarely, can develop in these lesions.

Figure 9-8. Nevus spilus (A) This dark brown pigmented macule measuring about 10 cm along the long axis is peppered with many small, dark brown to black macules and papules. (B) This is also nevus spilus but the macular background is only slightly pigmented so that it will be revealed only under Wood light. The lesion is peppered with many small dark brown macules and flat papules.

Figure 9-9. Spitz nevus (A) Pink dome-shaped nodule on the cheek of a young woman, developing abruptly within the previous 12 months; the lesion can be mistaken for a hemangioma. (B) Pigmented Spitz nevus. A black papule surrounded by a tan macular region developed within a few months on the back of a young female; as such a lesion cannot be distinguished from a nodular melanoma, the lesion was excised and the diagnosis confirmed histologically.

Figure 9-10. Mongolian spot A large gray-blue macular lesion involving the entire lumbosacral and gluteal area and the left thigh in a baby from Sri Lanka. Although Mongolian spots are common in Asians, the parents of this baby were alarmed because the lesion was so large.

Figure 9-11. Mongolian spots Multiple, ill-defined, bluish lesions are scattered on the back of this Japanese child. They were present at birth. Most of these lesions disappeared later in childhood.

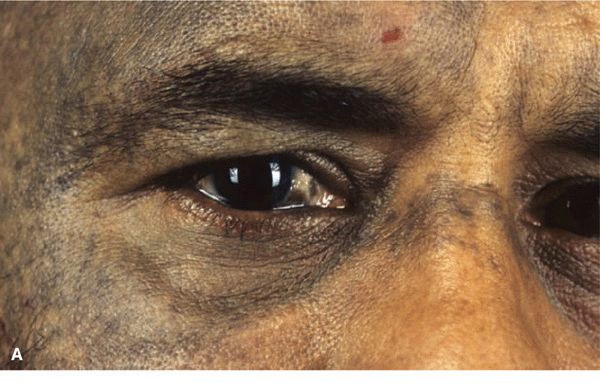

Figure 9-12. Nevus of Ota (A) There is an ill-defined, mottled, dusky, gray to bluish hyperpigmentation in the regions supplied by the first and second branches of the trigeminal nerve. The lesion was unilateral and there was also hyperpigmentation of the sclera and eyelids. (B). Bilateral nevus of Ota with involvement of the sclerae in a Japanese child.

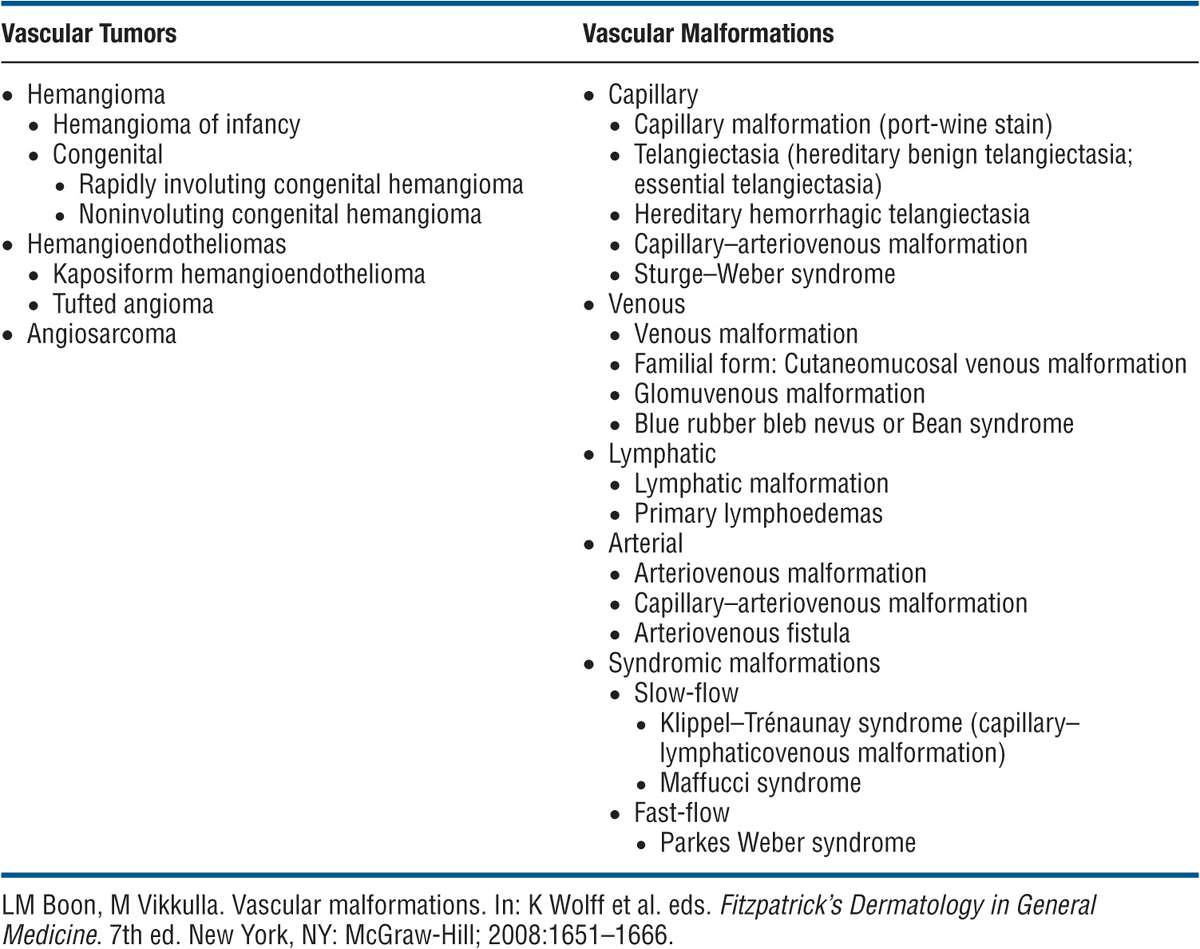

TABLE 9-1 CLASSIFICATION OF VASCULAR ANOMALIES

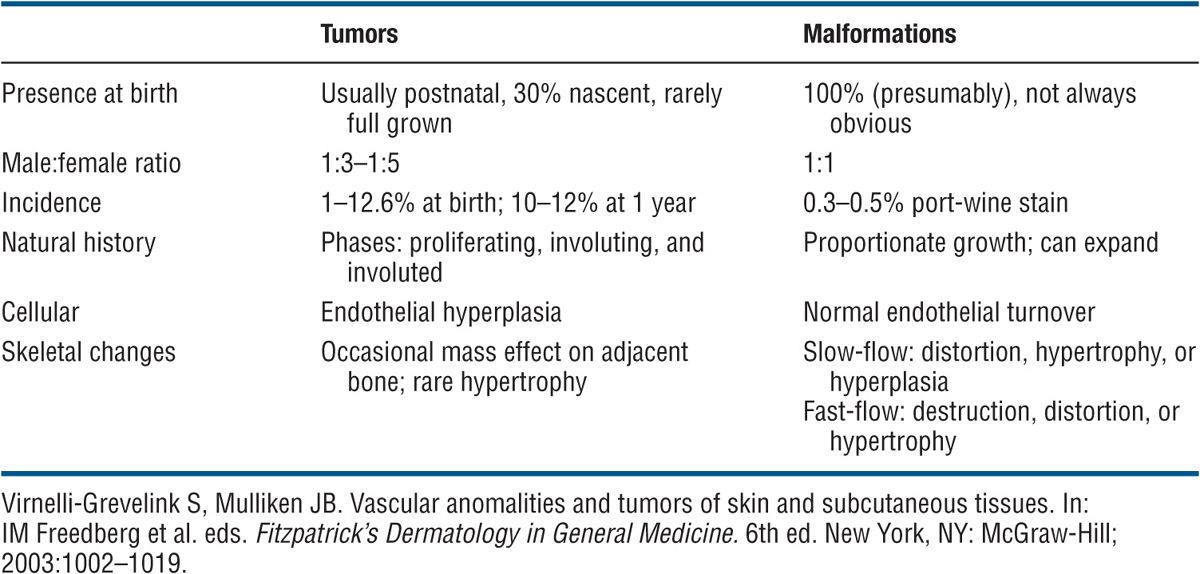

TABLE 9-2 DISTINGUISHING FEATURES OF VASCULAR TUMORS (HEMANGIOMAS) AND VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

Epidemiology

The most common tumor of infancy. Incidence in newborns between 1% and 2.5%; in white children by 1 year of age 10%. Females to males ratio is 3 to 1.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

HI is a localized proliferative process of angioblastic mesenchyme. A clonal expansion of endothelial cells resulting from somatic mutations of genes regulating endothelial cell proliferation.

Clinical Manifestation

The initial proliferative phase lasts from 3 to 9 months. His usually enlarge rapidly during the first year. In a subsequent phase of involution, the HI regresses gradually over 2–6 years. Involution is usually completed by the age of 10 and varies greatly between individuals. It is not correlated with size, location, or appearance of the lesion.

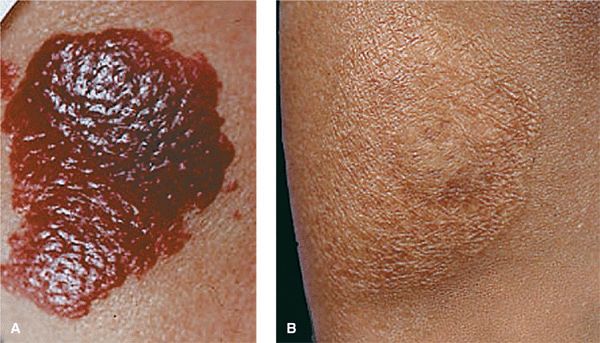

Skin Lesions. Soft, bright red to deep purple, compressible. On diascopy, does not blanch completely. Nodule or plaque, 1–8 cm (Figs. 9-13A and 9-14A). With the onset of spontaneous regression, a white-to-gray area appears on the surface of the central part of the lesion (Fig. 9-14A). Ulceration may occur.

Figure 9-13. Hemangioma of infancy (A) This bright red nodular plaque in an infant of African extraction is frightening to the parents, and caution is needed to prevent scarring from the treatment itself. Since most of these lesions disappear spontaneously with only 20% showing residual atrophy or depigmentation, a wait-and-see strategy is recommended. (B) The same lesion after 3 years. The hemangioma has faded spontaneously, and there is only slight residual atrophy.

Figure 9-14. Hemangioma of infancy (A) This lesion on the nose consists of a superficial and deep portion, and incipient involution is already apparent for the superficial compartment. Note an additional small hemangioma of infancy on the left zygomatic region. (B) By the fifth year, the hemangioma on the nose has almost disappeared and so has the lesion on the zygomatic region; the latter, however, that has left a small scar.

Distribution. Lesions are usually solitary and localized or extended over an entire region (Fig. 9-15). Head and neck 50% and trunk 25%. Face, trunk, legs, and oral mucous membrane.

Figure 9-15. Hemangioma of infancy Here it involves a large segment of skin. While involution is already apparent on the forehead, the lesion on the upper eyelid and the medial canthus is impairing proper function of the lid, and this indicates that vision might be impaired in the future. In this patient, treatment was indicated.

Special Presentations

Deep HI. (Formerly, cavernous hemangioma.) In the lower dermis and subcutaneous fat. Localized, firm rubbery mass of bluish or normal skin color with telangiectases in overlying skin (Fig. 9-16). Can be combined with superficial hemangioma (Fig. 9-14A). Does not involute as well as superficial type.

Figure 9-16. Hemangioma of infancy, deep lesion There is a rubbery mass in the subcutis associated with a superficial (red) portion. These lesions hardly regress. The hemangioma was removed by surgery.

Multiple His. Multiple small (<2 cm), cherry-red papular lesions involving skin alone (benign cutaneous hemangiomatosis) or skin and internal organs (diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis).

Congenital Hemangiomas. These develop in utero and are subdivided into rapidly involuting congenital hemangiomas (RICH) and non-involuting congenital hemangiomas (NICH). They present as violaceous tumors with overlying telangiectasia with large veins in periphery or as red-violaceous plaques invading deeper tissues. NICH are fast-flow hemangiomas requiring surgery.

Laboratory Examination

Dermatopathology. Proliferation of endothelial cells in various amounts in the dermis and/or subcutaneous tissue; there is usually more endothelial proliferation in the superficial type and little in the deep angiomas. GLUT-1 immunoreactivity is found in all hemangiomas but not in vascular malformations.

Diagnosis

Made on clinical findings and MRI; Doppler and arteriography to demonstrate fast flow. Determine GLUT-1 immunoreactivity to rule out vascular malformation.

Course and Prognosis

HIs spontaneously involute by the fifth year, with some few percent disappearing only by age 10 (Figs. 9-13B and 9-14B). There is virtually no residual skin change at the site in most lesions (80%); in the rest there is atrophy, depigmentation, telangiectasia, and scarring. HIs may, however, pose a considerable problem during the growth phase when they interfere with vital functions, such as obstruction of vision (Fig. 9-15) or of larynx, nose, or mouth. Deeper lesions, especially those involving mucous membranes, may not involute completely. Synovial involvement may be associated with hemophilia-like arthropathy. Special forms of HI, tufted angiomas and Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, may have platelet entrapment, thrombocytopenia (Kasabach–Merritt syndrome), and even disseminated intravascular coagulation. Rarely, morbidity associated with HI occurs secondary to hemorrhage or high-output heart failure.

Management

Each lesion must be judged individually regarding the decision to treat or not to treat and the selection of a treatment mode. Systemic treatment is difficult, requires experience, and should be performed by an expert. Surgical and medical interventions include continuous wave or pulsed dye laser, cryosurgery, intralesional and systemic high-dose glucocorticoids, interferon-α (IFN-α), and propranolol. For the majority of HIs, active nonintervention is the best approach because spontaneous resolution gives the best cosmetic results (Figs. 9-13B and 9-14B). Treatment is indicated in about a quarter of HIs (5% that ulcerate; 20% that obstruct vital structures, i.e., eyes, ears, larynx).

NMN, commonly called moles, are very common, small (<1 cm), circumscribed, acquired pigmented macules, papules, or nodules.

NMN, commonly called moles, are very common, small (<1 cm), circumscribed, acquired pigmented macules, papules, or nodules. Composed of groups of melanocytic nevus cells located in the epidermis, dermis, and, rarely, subcutaneous tissue.

Composed of groups of melanocytic nevus cells located in the epidermis, dermis, and, rarely, subcutaneous tissue. They are benign, acquired tumors arising as nevus cell clusters at the dermal–epidermal junction (junctional NMN), invading the papillary dermis (compound NMN), and ending their life cycle as dermal NMN with nevus cells located exclusively in the dermis where, with progressive age, there will be fibrosis.

They are benign, acquired tumors arising as nevus cell clusters at the dermal–epidermal junction (junctional NMN), invading the papillary dermis (compound NMN), and ending their life cycle as dermal NMN with nevus cells located exclusively in the dermis where, with progressive age, there will be fibrosis.

An NMN that is encircled by a halo of leukoderma or depigmentation. The leukoderma is based on a decrease of melanin in melanocytes and/or disappearance of melanocytes at the dermal–epidermal junction (

An NMN that is encircled by a halo of leukoderma or depigmentation. The leukoderma is based on a decrease of melanin in melanocytes and/or disappearance of melanocytes at the dermal–epidermal junction ( Mechanism: autoimmune (cellular, humoral) mechanism leading to apoptosis of nevus cells and melanocytes in surrounding epidermis.

Mechanism: autoimmune (cellular, humoral) mechanism leading to apoptosis of nevus cells and melanocytes in surrounding epidermis. Prevalence 1%. Occurs spontaneously or in patients with vitiligo.

Prevalence 1%. Occurs spontaneously or in patients with vitiligo. A white halo around a NMN indicates regression and halo nevi most often undergo spontaneous involution.

A white halo around a NMN indicates regression and halo nevi most often undergo spontaneous involution. Usually in children or young adults mostly on the trunk (

Usually in children or young adults mostly on the trunk ( Three stages: (1) white halo around preexisting NMN (

Three stages: (1) white halo around preexisting NMN ( Halo NMN may indicate incipient vitiligo.

Halo NMN may indicate incipient vitiligo. Halo around other lesions: blue nevus, congenital NMN, Spitz nevus, malignant melanoma and melanoma metastases, dermatofibroma, neurofibroma.

Halo around other lesions: blue nevus, congenital NMN, Spitz nevus, malignant melanoma and melanoma metastases, dermatofibroma, neurofibroma. Synonym: Sutton leukoderma acquisitum centrifugum.

Synonym: Sutton leukoderma acquisitum centrifugum.

A blue nevus is an acquired, firm, dark-blue to gray-to-black, sharply defined papule or nodule representing a localized proliferation of melanin-producing dermal melanocytes.

A blue nevus is an acquired, firm, dark-blue to gray-to-black, sharply defined papule or nodule representing a localized proliferation of melanin-producing dermal melanocytes. Three types: common blue nevus, cellular blue nevus, combined NMN/blue nevus.

Three types: common blue nevus, cellular blue nevus, combined NMN/blue nevus. Blue nevi and combined NMN/blue nevi are benign. Cellular blue nevi are larger and have very rare tendency to become malignant.

Blue nevi and combined NMN/blue nevi are benign. Cellular blue nevi are larger and have very rare tendency to become malignant. Ectopic accumulation of melanin-producing melanocytes; derived from melanoblasts arrested during migration from neural crest.

Ectopic accumulation of melanin-producing melanocytes; derived from melanoblasts arrested during migration from neural crest. Papules, nodules, blue-gray, blue-black, <10 mm in diameter (

Papules, nodules, blue-gray, blue-black, <10 mm in diameter ( Differential diagnosis: dermatofibroma, glomus tumor, nodular or metastatic melanoma, traumatic tattoo, pigmented BCC.

Differential diagnosis: dermatofibroma, glomus tumor, nodular or metastatic melanoma, traumatic tattoo, pigmented BCC. Treatment not necessary. If in doubt, excision.

Treatment not necessary. If in doubt, excision. Cellular blue nevi should be excised.

Cellular blue nevi should be excised. Synonyms: Blue neuronevus, dermal melanocytoma.

Synonyms: Blue neuronevus, dermal melanocytoma.

Light brown pigmented macule varying from a few centimeters to a large area (>15 cm), and many dark brown small macules (2–3 mm) or papules scattered throughout the pigmented background (

Light brown pigmented macule varying from a few centimeters to a large area (>15 cm), and many dark brown small macules (2–3 mm) or papules scattered throughout the pigmented background ( The pathology of the macular pigmented lesion is the same as lentigo simplex, i.e., increased numbers of melanocytes, while the flat or raised lesions scattered throughout are either junctional or compound; rarely, these may be DN.

The pathology of the macular pigmented lesion is the same as lentigo simplex, i.e., increased numbers of melanocytes, while the flat or raised lesions scattered throughout are either junctional or compound; rarely, these may be DN. The lesions are not as common as junctional or compound NMN but are not at all rare. In one series, the nevus spilus was present in 3% of white patients.

The lesions are not as common as junctional or compound NMN but are not at all rare. In one series, the nevus spilus was present in 3% of white patients. Malignant melanoma very rarely arises in these lesions.

Malignant melanoma very rarely arises in these lesions.

Spitz nevus is a benign, dome-shaped, hairless, small (<1 cm in diameter) nodule, most often pink, red or tan (

Spitz nevus is a benign, dome-shaped, hairless, small (<1 cm in diameter) nodule, most often pink, red or tan ( Incidence is 1.4:100,000 (Australia). It occurs at all ages but a third of the patients are children <10 years; rarely seen in persons >40 years. Lesions arise within months. They are papules or dome-shaped or relatively flat nodules, round, well-circumscribed, smooth-topped, and hairless. They are a uniform pink-red (

Incidence is 1.4:100,000 (Australia). It occurs at all ages but a third of the patients are children <10 years; rarely seen in persons >40 years. Lesions arise within months. They are papules or dome-shaped or relatively flat nodules, round, well-circumscribed, smooth-topped, and hairless. They are a uniform pink-red ( Differential diagnosis includes all pink, tan, or darkly pigmented papules: pyogenic granulom, hemangioma, molluscum contagiosum, juvenile xanthogranuloma, mastocytoma, dermatofibroma, NMN, DN (amelanotic), nodular melanoma.

Differential diagnosis includes all pink, tan, or darkly pigmented papules: pyogenic granulom, hemangioma, molluscum contagiosum, juvenile xanthogranuloma, mastocytoma, dermatofibroma, NMN, DN (amelanotic), nodular melanoma. Dermatopathology: hyperplasia of the epidermis and melanocytes and dilation of capillaries. Admixed large epithelioid cells, large spindle cells with abundant cytoplasm, and occasional mitotic figures. Sometimes bizarre cytologic patterns: nests of large cells extend from the epidermis (“raining down”) into the reticular dermis as fascicles of cells form an “inverted triangle,” with the base lying at the dermal–epidermal junction and the apex in the reticular dermis.

Dermatopathology: hyperplasia of the epidermis and melanocytes and dilation of capillaries. Admixed large epithelioid cells, large spindle cells with abundant cytoplasm, and occasional mitotic figures. Sometimes bizarre cytologic patterns: nests of large cells extend from the epidermis (“raining down”) into the reticular dermis as fascicles of cells form an “inverted triangle,” with the base lying at the dermal–epidermal junction and the apex in the reticular dermis. Histologic examination must be done to confirm the clinical diagnosis. Excision in its entirety is important because the condition recurs in 10–15% of all cases in lesions that have not been excised completely. Spitz nevi are benign, but there can be a histologic similarity to melanoma and the histopathologic diagnosis requires the help of an experienced dermatopathologist.

Histologic examination must be done to confirm the clinical diagnosis. Excision in its entirety is important because the condition recurs in 10–15% of all cases in lesions that have not been excised completely. Spitz nevi are benign, but there can be a histologic similarity to melanoma and the histopathologic diagnosis requires the help of an experienced dermatopathologist. Spitz nevi do not usually involute, as do common acquired NMN nevi. However, some lesions have been observed to transform into common compound NMN, and some undergo fibrosis and in late stages may resemble dermatofibromas.

Spitz nevi do not usually involute, as do common acquired NMN nevi. However, some lesions have been observed to transform into common compound NMN, and some undergo fibrosis and in late stages may resemble dermatofibromas. Synonyms: Pigmented and epithelioid spindle cell nevus. Years ago these were called “juvenile melanoma.”

Synonyms: Pigmented and epithelioid spindle cell nevus. Years ago these were called “juvenile melanoma.”

These congenital gray-blue macular lesions are characteristically located on the lumbosacral area (

These congenital gray-blue macular lesions are characteristically located on the lumbosacral area ( The underlying pathology is dispersed spindle-shaped melanocytes within the dermis (dermal melanocytosis). Melanocytes are not normally present in the dermis, and it is believed that these ectopic melanocytes represent pigment cells that have been interrupted in their migration from the neural crest to the epidermis.

The underlying pathology is dispersed spindle-shaped melanocytes within the dermis (dermal melanocytosis). Melanocytes are not normally present in the dermis, and it is believed that these ectopic melanocytes represent pigment cells that have been interrupted in their migration from the neural crest to the epidermis. Mongolian spots may disappear in early childhood, in contrast to nevus of Ota (see

Mongolian spots may disappear in early childhood, in contrast to nevus of Ota (see  As the term Mongolian implies, these lesions are found almost always (99–100%) in infants of Asiatic and Native American origin; however, they have been reported in black and, rarely, in white infants.

As the term Mongolian implies, these lesions are found almost always (99–100%) in infants of Asiatic and Native American origin; however, they have been reported in black and, rarely, in white infants. No melanomas have been reported to occur in these lesions.

No melanomas have been reported to occur in these lesions.

Very common in Asian populations and is said to occur in 1% of dermatologic outpatients in Japan. It has been reported in East Indians, blacks, and, rarely, whites.

Very common in Asian populations and is said to occur in 1% of dermatologic outpatients in Japan. It has been reported in East Indians, blacks, and, rarely, whites. The pigmentation, which can be quite subtle or markedly disfiguring, consists of a mottled, dusky admixture of blue and brown hyperpigmentation of the skin. It mostly involves the skin and mucous membranes innervated by the first and second branches of the trigeminal nerve (

The pigmentation, which can be quite subtle or markedly disfiguring, consists of a mottled, dusky admixture of blue and brown hyperpigmentation of the skin. It mostly involves the skin and mucous membranes innervated by the first and second branches of the trigeminal nerve ( The blue hue results from the presence of ectopic melanocytes in the dermis. It can occur in the hard palate and in the conjunctivae (

The blue hue results from the presence of ectopic melanocytes in the dermis. It can occur in the hard palate and in the conjunctivae ( Nevus of Ota may be bilateral (

Nevus of Ota may be bilateral ( Treatment with lasers is an effective modality for this disfiguring disorder.

Treatment with lasers is an effective modality for this disfiguring disorder. Malignant melanoma can occur but is rare.

Malignant melanoma can occur but is rare. The present binary biologic classification distinguishes between vascular tumors and vascular malformations. The latter are subclassified according to the structural components into capillary, venous, lymphatic, arterial, or combined forms (

The present binary biologic classification distinguishes between vascular tumors and vascular malformations. The latter are subclassified according to the structural components into capillary, venous, lymphatic, arterial, or combined forms ( Vascular tumors (e.g., hemangiomas) show endothelial hyperplasia, whereas malformations have a normal endothelial turnover.

Vascular tumors (e.g., hemangiomas) show endothelial hyperplasia, whereas malformations have a normal endothelial turnover. Hemangiomas of infancy are not present at birth but appear postnatally; grow rapidly during the first year (proliferating phase), undergo slow spontaneous regression during childhood (involution phase), and remain stable thereafter.

Hemangiomas of infancy are not present at birth but appear postnatally; grow rapidly during the first year (proliferating phase), undergo slow spontaneous regression during childhood (involution phase), and remain stable thereafter. Vascular malformations are errors of morphogenesis and are presumed to occur during intrauterine life. Most are present at birth, though some do not appear until years later. Once manifested they grow proportionally, but enlargement can occur as a result of various factors.

Vascular malformations are errors of morphogenesis and are presumed to occur during intrauterine life. Most are present at birth, though some do not appear until years later. Once manifested they grow proportionally, but enlargement can occur as a result of various factors. Both vascular tumors and malformations can be separated into slow-flow or fast-flow types.

Both vascular tumors and malformations can be separated into slow-flow or fast-flow types. Classification of vascular tumors and malformations is shown in

Classification of vascular tumors and malformations is shown in