Cutaneous Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma, not Otherwise Specified (NOS)

Cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (NOS) represents a “waste basket” of all cases that cannot be put into another of the categories of mature cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Occurrence in the skin is not well documented and probably represents in most instances a secondary involvement by extracutaneous disease (usually nodal). In the past cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS was lumped in the group of “CD30− medium/large pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma” [1–3].

In the World health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS, is defined as a heterogeneous category of nodal and extranodal neoplasms that cannot be classified within one of the specific entities of mature T-cell lymphoma [4], thus representing a diagnosis of exclusion. In my experience, most cutaneous cases, even those with a CD4+ phenotype, express one or more cytotoxic proteins, thus belonging conceptually to the group of cytotoxic natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphomas.

Besides the lack of well-documented studies, the major problem in the skin is that other cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, particularly cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoma, may present with histopathological and phenotypical features identical to those of cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS. Differentiation of these two entities may be subjective, as precise criteria have not been established. For a detailed discussion on differential diagnostic features see Chapter 8.

As for other rare types of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, mycosis fungoides should be ruled out before a diagnosis of cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS, can be accepted. Complete staging investigations are mandatory and in my experience reveal a primary extracutaneous disease in most instances. Treatment, on the other hand, is independent from staging results, for even if no extracutaneous disease is found aggressive options should be selected.

At the present stage of knowledge, for a diagnosis of cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS, the following criteria should be fulfilled:

- Absence of other lesions and/or clinical history of mycosis fungoides.

- Clinically, presence of multiple lesions or of rapidly growing tumors outside the head and neck region (although conceptually it is not impossible that peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS, arises with solitary lesions on the head and neck area, for practical purposes such cases should be classified as cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoma unless compelling evidence proves otherwise).

- Histopathologically, the presence of nodular or diffuse infiltrates of small, medium or large T lymphocytes, usually with pleomorphic nuclei.

- α/β phenotype of neoplastic cells (γ/δ cases should be classified as cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma).

- Absence of prominent epidermotropism of CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes (cases showing these features should be better classified as cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma).

- Negativity for CD30 or positivity in a minority of cells (positive cases should be better classified as cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma).

- Absence of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) within neoplastic cells (positive cases should be better classified as cutaneous extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type).

Clinical Features

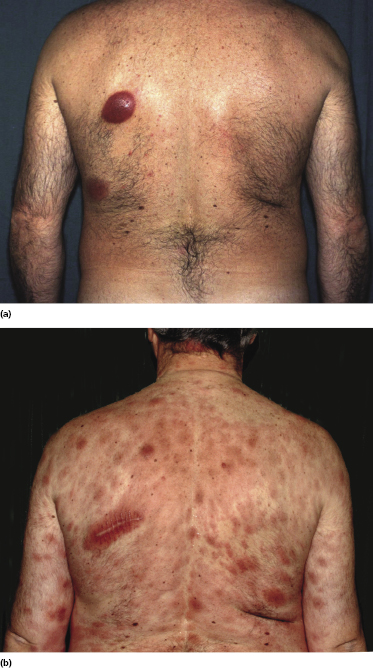

Patients are adults of both genders. There are reports on children and adolescents with cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS, but it is unclear whether the neoplasm was primary cutaneous or represented secondary skin involvement from a nodal lymphoma [5]. Patients present usually with regionally localized or generalized tumors (Fig. 7.1). Ulceration may be present. Sometimes multiple localized papules may resemble clinically persistent arthropod bite reactions (Fig. 7.2). In patients with secondary skin involvement I have observed rarely infiltrated, large flat erythematous lesions (Fig. 7.3) or purpuric papules mimicking a vasculitis (Fig. 7.4).

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

Histopathology

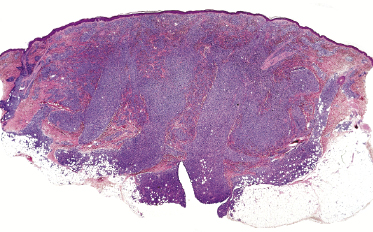

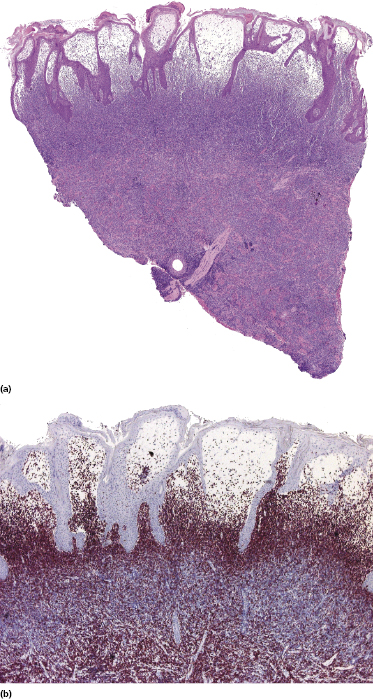

Histology shows nodular or diffuse infiltrates involving the entire dermis and subcutaneous fat. Small, medium-sized and large pleomorphic cells may all be observed in variable proportions (Figs 7.5 and 7.6). Epidermotropism may be present, but it is never pronounced. A high mitotic rate is found, particularly in tumoral infiltrates. Prominent necrosis, presence of angiocentricity, and/or angiodestruction or predominant involvement of the subcutaneous tissues are uncommon.

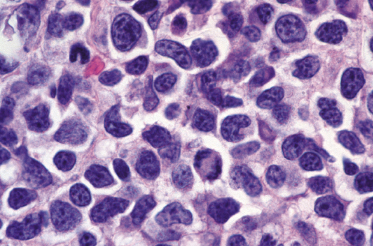

Early lesions may show only moderately dense, perivascular and periadnexal lymphoid infiltrates of small- and medium-sized lymphocytes (Fig. 7.7). If present, infiltration and/or destruction of adnexal structures is a helpful diagnostic clue in such cases. Edema may be observed (Fig. 7.8a).

Immunophenotype

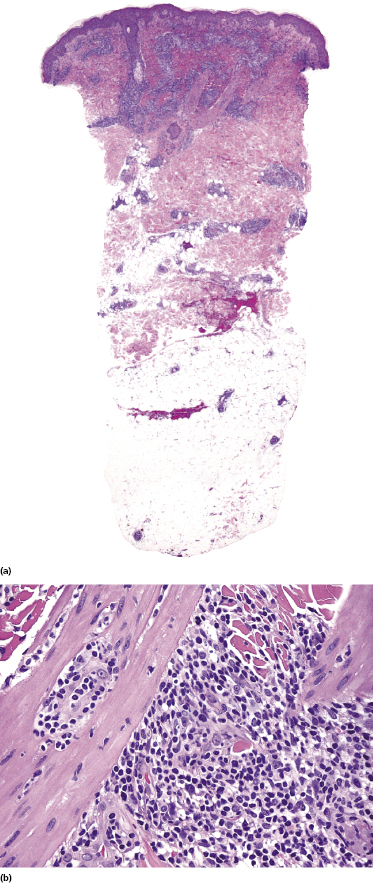

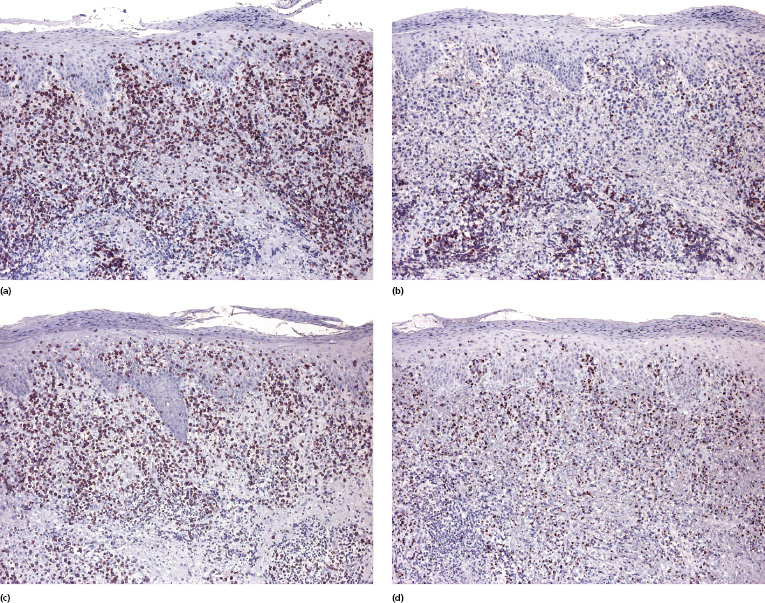

Immunohistology reveals a characteristic phenotype of neoplastic cells (βF1+, CD4+/−, CD8−), commonly with loss of one or more pan-T-cell antigens (Fig. 7.9a to c). A phenotype switch may be observed in recurrent lesions [6]. CD30 and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) are negative, whereas CD56 may be positive in some cases. Cytotoxic proteins (TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin) are expressed in the great majority of cases (Fig. 7.9d) [7, 8]. The proliferation rate is usually high. There is no association with EBV infection.

A small proportion of nodal cases express the phenotype of follicular helper T-lymphocytes (TFH) (Fig. 7.8b). Only sporadic cutaneous cases with this phenotype have been reported [9]. One case described by Marzano et al. had the phenotype of T regulatory cells (Tregs) with positivity for FOX-P3 [10].

Molecular Genetics

Molecular analysis of the T-cell receptor (TCR) genes reveals a monoclonal rearrangement in most cases. Nodal cases show frequent gains of 1q, 3p, 5p, 7q, 8q, 9p, and 19q and losses of 3q, 6q, 9p, and 10p [11, 12]. A few cutaneous cases were characterized by gains of 7q, 8, and 17q, and loss of 9p21 [13].

Treatment

Patients should be managed in a hematologic setting. The treatment of choice is systemic chemotherapy using regimens for high-grade T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Several alternative treatments with monoclonal antibodies and other compounds are being investigated.

Prognosis

The prognosis of cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS, is very poor and most patients die within a few months from the onset of the disease. The estimated 5-year survival is less than 20% [14]. In nodal cases, a cytotoxic profile may be a poor prognostic sign [4]. The role of this phenotype in cutaneous cases has not been elucidated.

Cases expressing the chemokines CXCR3 and CCR4 may have a worse prognosis [15]. Other prognostic factors identified in nodal cases (but not verified in cutaneous ones) are the presence of >70% transformed blasts, proliferation rate of >25% (detected by staining with Ki-67), CD56 expression, and background of >10% CD8+ cells [15].

A better prognosis was observed in nodal cases showing FOX-P1 overexpression [16]. Cutaneous cases localized to the legs may be characterized by a more aggressive course [17].

Full access? Get Clinical Tree