Abstract

The cheek is one of the most important structural features of the facial architecture—signifying youthfulness, fertility, and beauty. It overlies the lateral zygomatic bone, but also encompasses the entire midface, including the tissues below the orbit. Facial fillers should be used in the midface as volumizing agents. Hyaluronic gel fillers can be as effective as fat grafting when used within facial fat pads to augment volume deflation changes. Restoring the volume of the midface is mandatory to improve sagging and drooping and lift central areas of heaviness.

When using facial fillers, we must assess aging in terms of both facial bone changes and fat atrophy. To improve signs of deep bony changes, supraperiosteal injections are placed in areas of bone reabsorption bounded by retaining ligaments and should be done with the highest G-prime fillers. Moderate depth fat pad augmentations are done best by moderate to high G-prime fillers, while more superficial subcutaneous deficiencies are augmented with mild to moderate G-prime fillers.

Targeting the four ligaments within the midface (zygomaticocutaneous, orbital, maxillary, and upper masseteric cutaneous ligaments) improves cheek tissue suspension. The nasolabial, infraorbital, superficial medial cheek, deep medial cheek, and the medial and lateral suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) compartments typically undergo volume loss. Boluses delivered along the superior, medial, and inferior border of the zygomatic arch that follow the natural contour of the zygoma enhance projection of the cheek bones. The efficacy of facial fillers to act as volumizing agents enables patients to have long-lasting results that are reliable and minimally invasive.

55 Part B: Filler Finesse: Cheeks

Key Points

Facial aging is multifactorial and involves a number of changes to the face including gradual loss of dermal collagen and subcutaneous fat occurs, causing subcutaneous volume loss in the nasolabial, infraorbital, superficial medial cheek, deep medial cheek, and the medial and lateral suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) compartments are most responsible for sagging and cheek deflation.

To counteract signs of facial aging, hyaluronic acid (HA) and non-hyaluronic acid (non-HA) injections are both excellent techniques for maintaining youthful projection of the malar fat pads. Both types of fillers differ significantly in terms of G-prime (elastic ability to resist compression), filler longevity, and reversibility. HA fillers have a low-to-high G-prime and are most beneficial to patients who require replacement of fat deflation, who desire a reversible filler, and who prefer a more subtle tissue augmentation. Non-HA fillers have a higher G-prime and can achieve a more contoured look. They are better suited to address deep bone and fat pads changes through their support and ability to induce primary and secondary neocollagenesis.

55B.1 Preoperative Steps

55B.1.1 Background Knowledge

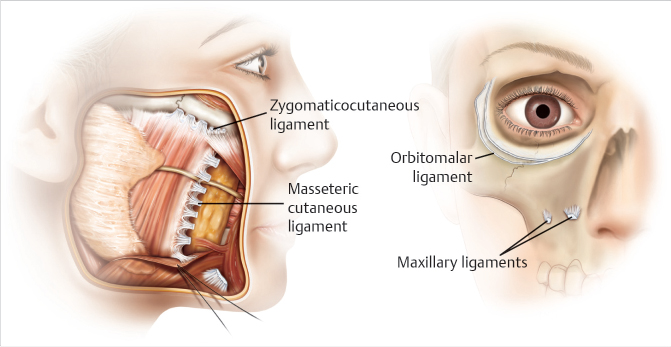

Several facial retaining ligaments throughout the buccal area anchor and stabilize the superficial and deep fascia, ensuring that the midface fat pads remain in their designated anatomical locations. The retaining ligaments of the midface are the zygomaticocutaneous, orbital, maxillary, and upper masseteric cutaneous ligaments (Fig. 55B.1). Because fat resorption mostly occurs within the bounds of these ligaments, palpating these ligaments at the surface of the skin exposes volume deflation and thinning of the fat pads that will benefit from correction.

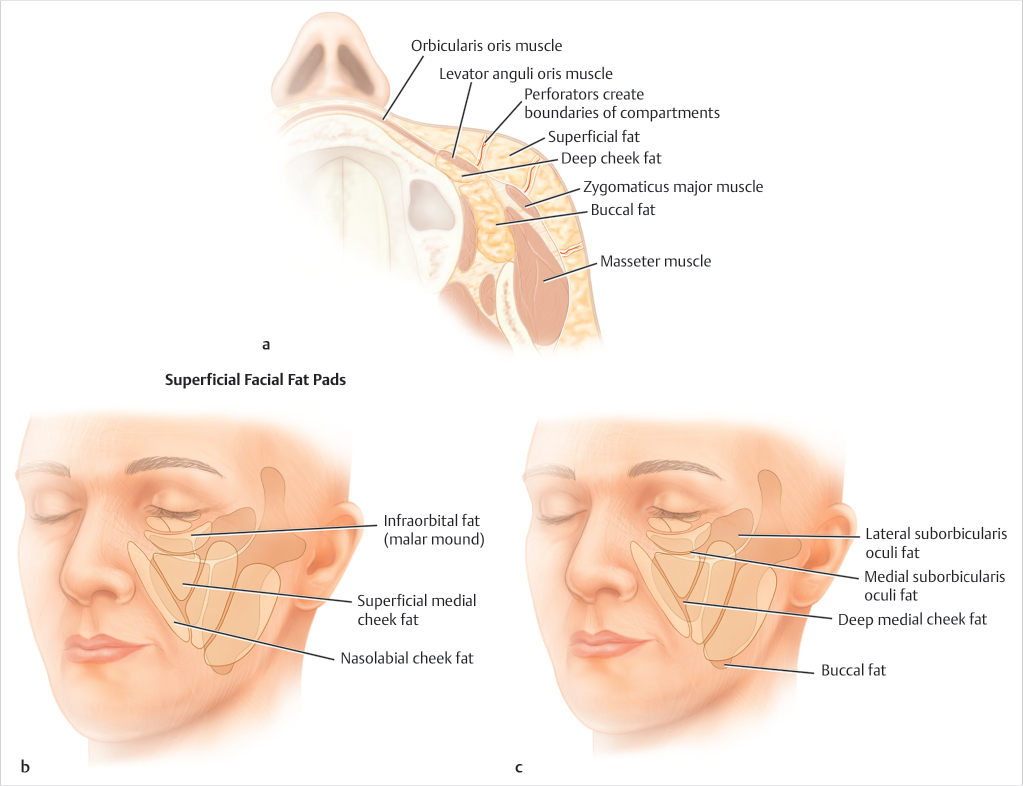

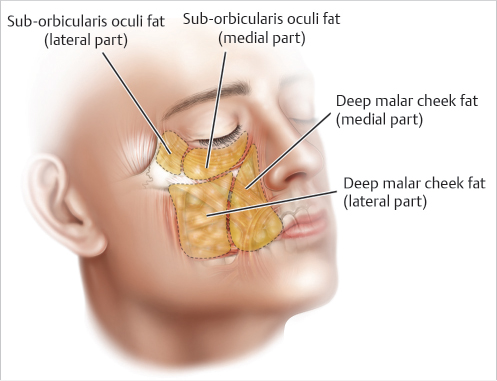

There are superficial and deep fat compartments within the midface that all contribute to malar soft tissue complex descent and lead to distinct morphological changes associated with facial aging such as volume depletion (Fig. 55B.2a–c). The three superficial facial fat compartments are the nasolabial, infraorbital, and superficial medial cheek fat pads. Deep fat regions include the medial and lateral SOOF, buccal, and deep medial cheek fat pads (as described by Wan, Amirlak, Rohrich, and Davis in The Clinical Importance of the Fat Compartments in Midfacial Aging).

55B.2 Pretreatment Analysis

55B.2.1 Filler Selection

Patients new to fillers or concerned about long-term facial structural changes are recommended to use HA fillers, as their effects can be reversed and dissolved. Both HA and non-HA fillers are typically viable for 12 to 24 months. Patients who exhibit soft tissue and subcutaneous changes with dermal thinning benefit from HA fillers, as their variety of G-primes—from low to intermediate to high—enable the filler to better integrate with the tissues to provide a more superficial placement and softening of etched lines. For correction in areas with weakened ligamentous and soft-tissue support, consider using a moderate-to-high G-prime filler in certain areas of the fat compartments and sub-superficial musculoaponeurotic system (sub-SMAS) space.

The sculpted, contoured aesthetic that often appeals to younger patients can be best achieved with non-HA fillers such as calcium hydroxylapatite. Its high G-prime and viscoelastic properties allow for structural mimicking of the bony zygoma, which ensures maximal projection. Calcium hydroxylapatite is a biostimulator that induces primary and secondary neocollagenesis—the latter facilitates a long-term effect. Patients with sensitive skin or history of reaction to other injectables should consider non-HA over HA, as non-HA is biocompatible with human tissue and is inert and nonantigenic.

55B.2.2 Anatomy Assessment

Bisect the face and palpate the zygomatic bone structure bilaterally to assess for asymmetry, deflation, and drooping of the fat pads and jowling.

Palpate for the zygomaticocutaneous, orbital, maxillary, and masseteric retaining ligaments and assess any weakening connections that affect the ligaments’ ability to restrain facial skin against gravitational effects. The zygomaticocutaneous ligament originates from the inferior aspect of the zygomatic arch and expands anteriorly toward the junction between the zygomatic body and arch. The orbital retaining ligament extends along the orbital aperture and terminates where the lateral orbit thickens. The maxillary retaining ligaments are superficial to the maxilla, originating from the masseteric fascia and lying on top of the masseter muscle.

Evaluate the malar mound and the superficial cheek fat compartments (Fig. 55B.2a–c). The infraorbital fat is located between the orbicularis retaining ligament and the zygomaticocutaneous ligaments at the subcutaneous level and is a continuation of the tear trough. Injections into this area are associated with increased risk of lymphatic damage and edema.

Nasolabial folds are one of the most prominent signs of facial aging and are best treated by supporting descending malar fat pads to lift their gravitational weight on the nasolabial folds. As described by Lamb and Surek in their textbook, Facial Volumization: An Anatomic Approach, volume loss associated with aging is thought to begin in the lateral superficial compartment and progress medially, which correlates with severity of facial aging. Adding volume to these compartments provides support and lift to the cutaneous structures and facilitates proper distribution of tension within the collagenous subdermal fibers. Injecting perpendicular to Langer’s lines allows for more natural cheek contouring.

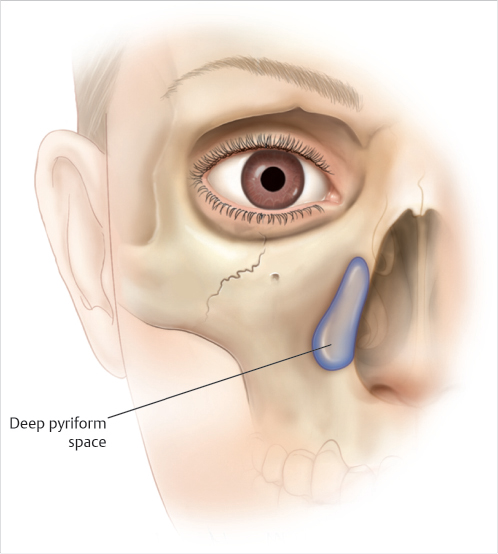

In older patients, the deep pyriform space (Fig. 55B.3), located deep and anterior to the maxilla requires analysis because the pyriform aperture recesses with age, resulting in enlargement of this hollow. Injecting filler into this site via cannula allows for volumization and lift to the lower midface. Filler can be delivered safely without the risk of intravascular compromise as the angular artery is not within the injection plane and courses laterally and superficially to this space. The deep medial cheek fat pad and Ristow’s space are critical to volumize as well in this manner.

The deep fat pads require evaluation as well because older patients commonly experience deflation in these regions. Deep medial cheek fat consists of medial and lateral components: the medial component is anterior to the premaxillary space and posterior to the deep pyriform space whereas the lateral component neighbors the buccal space and bony maxillary depression (Fig. 55B.4). Filler injection into the medial component and the deep pyriform space achieves effective volume enhancement. These injections should be placed deep and medial in the anterior cheek. The lateral component should not be injected into, as this is a high swelling risk area.

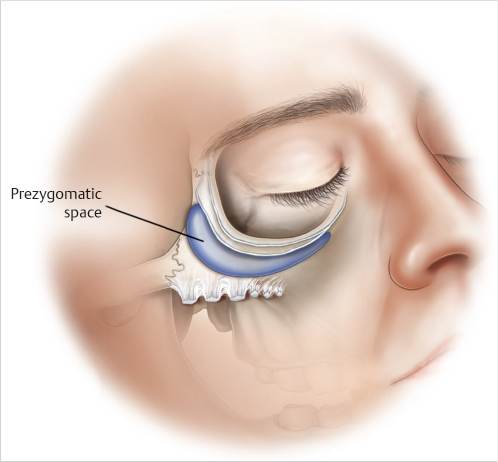

Injecting into the prezygomatic space (Fig. 55B.5) also allows for enhanced midface volumization. As described by Lamb and Surek in their textbook, Facial Volumization: An Anatomic Approach, this space is bounded by the orbital retaining ligaments, deep to the orbicularis oculi muscle and between the SOOF and the preperiosteal fat pad. The SOOF is a narrow fat layer that lies between the orbicularis oculi muscle and the posterior capsule of SMAS. A safe injection can be performed by pinching and retracting the skin and orbicularis upward, while inserting the cannula laterally into the prezygomatic space.

The premaxillary space should also be analyzed for hollowness. This space expands beneath the posterior capsule of the orbicularis oculi muscle. Great caution should be taken when injecting into this area, as the infraorbital neurovascular bundle lies deep to this space near the anterior surface of the levator labii superioris, and the angular vein courses laterally through the border of this space.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree