Subcutaneous Panniculitis-like T-cell Lymphoma

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma is included as a distinct entity in the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues [1]. As a degree of involvement of subcutaneous fat by neoplastic lymphocytes is common in many primary or secondary cutaneous T- and B-cell lymphomas, it is necessary to strictly separate true subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma from other lymphomas involving the subcutaneous fat.

Neoplastic cells in subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma are located exclusively within the subcutaneous fat and display an α/β cytotoxic T-cell phenotype [1–3]. Cases with a γ/δ T-cell phenotype do not belong to this group and should be classified separately (see Chapter 6). Since neoplastic cells in cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma may express CD8, a positive staining for the α/β receptor is mandatory for the diagnosis. When properly used, the term subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma encompasses a group of patients with relatively homogeneous clinicopathologic, phenotypic, and prognostic features. As in former times different entities were included in this group, readers should understand that criteria used in the past differ from those that are required today for a diagnosis of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma [1–3].

In the past, cases of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma were classified as malignant histiocytosis or histiocytic cytophagic panniculitis [4, 5]. Soon after the first description, it became clear that many cases of histiocytic cytophagic panniculitis showed a monoclonal population of T lymphocytes, proving the lymphoid origin of the disease [6]. It subsequently became clear that histiocytic cytophagic panniculitis was not always fatal, as previously thought, and that cases with a good prognosis could be observed [7]. Not all of the cases formerly classified as histiocytic cytophagic panniculitis belong to the group of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, and some probably represent examples of cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma or of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. In fact, involvement of the subcutis is common in these types of lymphoma (see Chapter 6) [2, 8, 9]. It has also been demonstrated that some cases classified in the past as Weber–Christian panniculitis represent in truth examples of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma [10, 11].

The literature on subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma is extremely confusing. In the past, based only on the involvement of the subcutis, many types of lymphoma with different clinicopathologic features and prognostic behavior have been lumped together in this group, and the exact definition and diagnostic criteria were unclear [8, 9, 11]. Moreover, any review of the literature is hindered by the fact that in many of the earlier cases phenotypic investigations were incomplete or not carried out at all. It must be clearly underlined that a purely subcutaneous pattern (“lobular panniculitis-like”) can be observed rarely in various cutaneous lymphomas of T- and B-cell phenotype and that a prominent involvement of the subcutis per se is not a sufficient criterion for the diagnosis of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma [2, 12–14]. In this context, it should be remembered also that many overlapping features can be observed in the group of so-called “cytotoxic lymphomas” (see Chapter 6), including subcutaneous involvement by neoplastic lymphocytes, and that multiple parameters are required to classify a given case into a precise category [2, 15]. Finally, lesions with exclusive subcutaneous involvement have also been observed in patients with mycosis fungoides [16]. An accurate clinical history should always be obtained in patients with a putative subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, and any skin lesions clinically suspicious of mycosis fungoides (e.g., superficial patches) should be biopsied.

It seems likely that at least some of the cases reported in the literature as lupus panniculitis (lupus erythematosus profundus) or “benign panniculitis evolving into overt lymphoma” represent in truth examples of slowly progressing subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma that had been misdiagnosed at the beginning [11]. In this context, it has been proposed that lupus panniculitis and subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma represent two ends of a spectrum of the same entity and the term “panniculitic T-cell dyscrasias” has been introduced in order to classify unclear cases [17]. I have observed some patients who presented with typical lesions of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma histopathologically, but with clinical features of lupus erythematosus (positivity of antinuclear antibodies or other clinical and/or serologic markers of the disease), and believe that “overlapping” cases may exist [18]. It is not unconceivable that some patients with lupus erythematosus may develop lesions of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma during the course of the disease. On the other hand, I do not believe that lupus panniculitis and subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma represent two ends of a spectrum, and in most cases the two conditions can be differentiated precisely (see also differential diagnosis with lupus panniculitis later in this chapter).

The etiology and pathogenesis of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma are still unknown. Autoimmune disorders, particularly lupus erythematous, are present in a distinct proportion of patients [3] and onset of the disease has been observed also in patients receiving immune modulatory drugs such as etanercept [19]. Transmission of the disease by allogeneic bone marrow transplantation has been documented in a single case [20], as well as onset in an immunosuppressed individual after cardiac transplantation [21]. A study showed that neoplastic lymphocytes express CCL5, a ligand for the C-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5), which is expressed by adipocytes, thus providing a possible explanation for the peculiar tropism of neoplastic T lymphocytes for the adipose tissues [22].

Clinical Features

Patients are adults of both sexes [1, 3, 23], often with a variably long history of “benign panniculitis” (particularly lupus panniculitis). Reports in children exist [24–26] and aggressive pediatric cases with hemophagocytic syndrome have been described as well [27]. In this context, it should be remembered that a lobular panniculitis with monoclonal CD8+ T-lymphocytes may be observed in children with congenital immune deficiency syndromes and that in this setting the diagnosis of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma should be made with extreme caution, if at all.

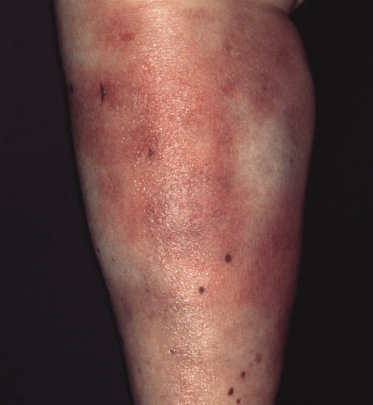

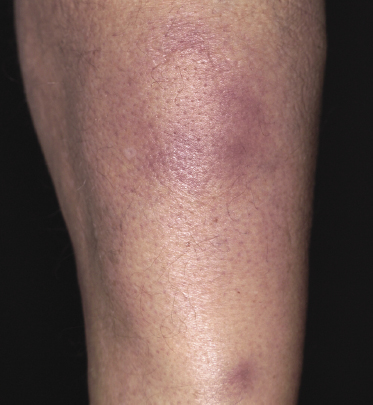

Clinically, patients present with solitary or multiple, infiltrated, “panniculitis-like” plaques or subcutaneous tumors. The lesions are usually not ulcerated and are located most commonly on the extremities, especially the lower ones (Figs 5.1 and 5.2). Other sites of the body, including the head, may be affected (Fig. 5.3). Skin lesions reveal nonspecific clinical features of panniculitis and may simulate erythema nodosum, lupus panniculitis, or other panniculitic diseases. One patient with alopecic lesions on the scalp has also been described, and one with a lesion on the leg resembling venous stasis ulceration [28, 29]. Spontaneous resolution of some of the lesions may be observed [9, 30]. It must be underlined that some of the clinical variants described in the past may in truth represent examples of other cytotoxic lymphomas with subcutaneous involvement, as in many cases phenotypic details were not sufficient to classify the cases precisely. In one patient, neoplastic T lymphocytes have been detected in the peripheral blood [31], but the clinical relevance of this finding, if any, has not been elucidated.

In a subset of patients (only a small minority) there are accompanying symptoms such as fever, malaise, fatigue, and weight loss, sometimes mimicking those of rheumatic diseases [32]. A history of autoimmune disorders, particularly lupus erythematosus, is present in about 20% of patients [3]. A hemophagocytic syndrome may be seen in advanced stages or rarely at first presentation, and can be the cause of death [3]. It should be underlined that the hemophagocytic syndrome is more common in the aggressive cytotoxic lymphomas with a γ/δ T-cell or NK-cell phenotype (see also Chapter 6).

As mentioned before, clinical features of lupus erythematosus may be coexistent with those of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma in a small minority of patients [18]. These features include positivity for antinuclear antibodies and subsets, hematologic changes (e.g., anemia, neutropenia), renal changes, and positive immunofluorescence test on lesional skin. It seems likely that in these cases a true association of both diseases exists.

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

Histopathology

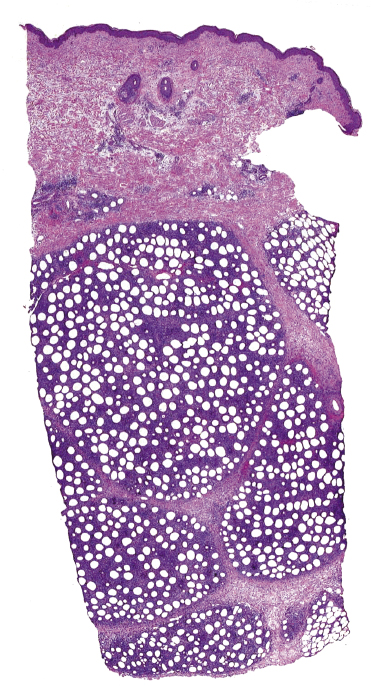

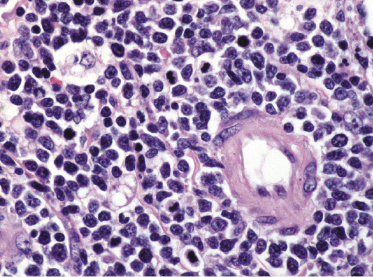

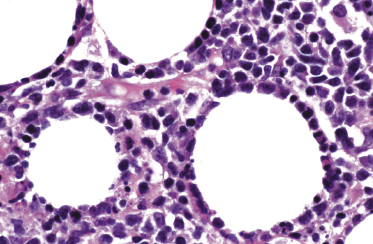

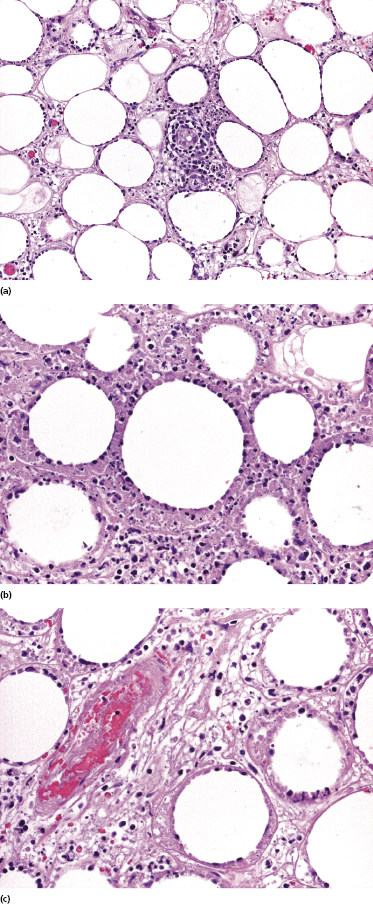

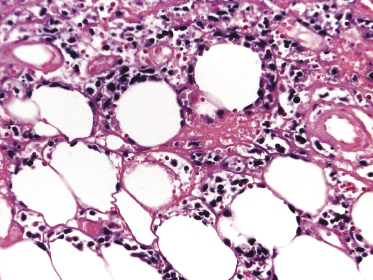

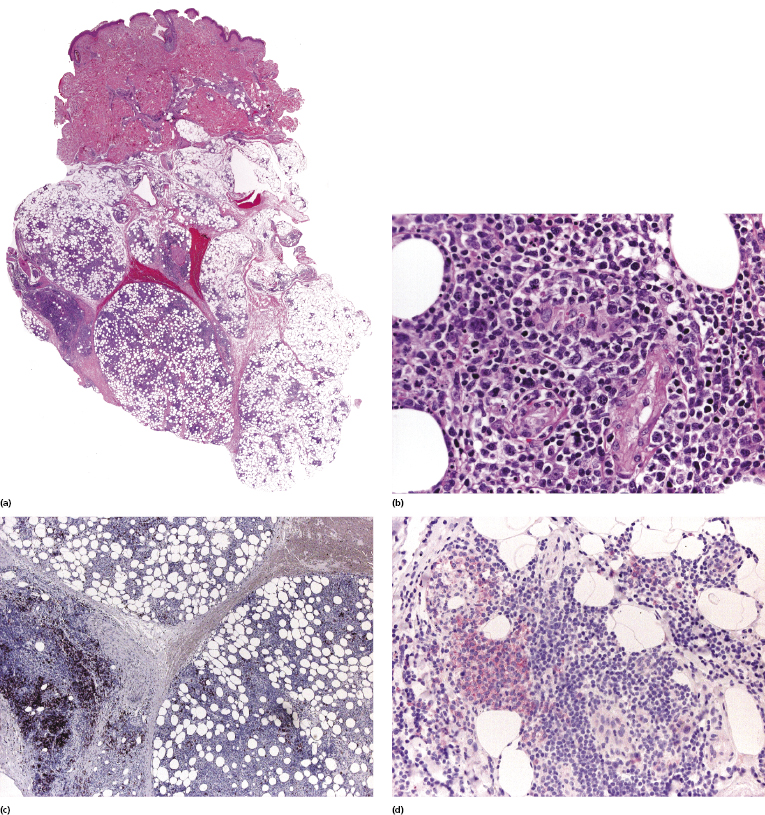

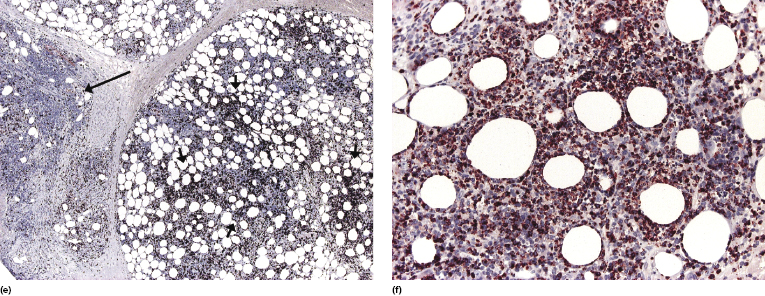

Histopathology reveals dense, nodular, or diffuse infiltrates of small, medium, and (rarely) large pleomorphic lymphocytes confined to the subcutaneous fat with the pattern of a lobular panniculitis (Figs 5.4 and 5.5). Small perivascular aggregates of non-neoplastic cells may be located within the reticular dermis, but clusters of neoplastic T lymphocytes are almost never situated outside the subcutaneous tissues. Epidermotropism is never found. Neoplastic cells within the subcutaneous fat are arranged in small clusters or as solitary units around the single adipocytes (so-called “rimming” of the adipocytes) (Fig. 5.6). Necrosis is often a prominent feature and may completely mask the specific histopathologic features. In such cases, clues to the diagnosis, if present, are the finding of small aggregates of atypical cells within the areas of necrosis (Fig. 5.7a) and of “ghost cells” (Fig. 5.7b), representing necrotic lymphocytes still showing the original distribution of the infiltrate. Angiocentricity/angiodestruction is uncommon, but necrotic vessels with intraluminal thrombi may be observed in the areas of necrosis (Fig. 5.7c). A histiocytic infiltrate, often with the formation of granulomas, is also frequent, particularly in late stages. In addition, reactive small lymphocytes can be admixed with the neoplastic cells, but plasma cells and eosinophils are rare. Membranocystic (lipomembranous) fat necrosis has been described in some cases [33].

Although “rimming” of adipocytes by neoplastic lymphocytes has often been described as a histopathologic feature diagnostic of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, a similar phenomenon can be observed in virtually all lymphomas with prominent involvement of the subcutaneous fat, as well as in reactive subcutaneous infiltrates [34]. In fact, I have observed B-cell lymphomas showing both clinical and histopathologic features indistinguishable from those of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma [12]. Necrosis and degenerative changes within the subcutaneous fat, which are often remarkable in subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, are only rarely found in subcutaneous infiltration of B-cell lymphomas.

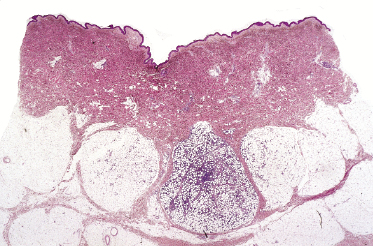

In some lesions of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma the specific findings are confined to a small portion of the subcutaneous fat, thus rendering the examination of small biopsies (i.e., punch biopsies) problematic or even impossible (Fig. 5.8). In this context, it must be underlined that a diagnosis of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma can only be made when large, deep biopsies are available.

In rare cases I have observed conventional lesions of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma showing changes of interface dermatitis at the dermo-epidermal junction. Particularly in these cases, the differential diagnosis from lupus panniculitis is possible only upon precise phenotypic characterization of the subcutaneous infiltrate. It may be that these cases represent genuine examples of overlapping lupus panniculitis and subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.

Immunohistology

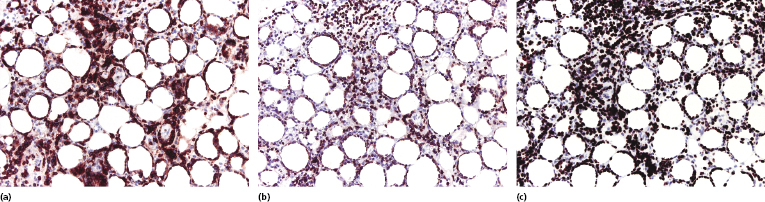

Immunohistologic analyses show an α/β T-cytotoxic phenotype of neoplastic cells (βF1+, CD3+, CD4−, CD8+) (Fig. 5.9a and b) [3]. As already mentioned, a positive staining for βF1, a marker of the T-cell receptor (TCR)-β, is necessary in order to confirm the diagnosis. Particularly in recurrent lesions, βF1 expression may get partially lost by neoplastic cells, but it is usually retained by at least a proportion of them (see Teaching case 5.1). A negative staining for TCR-γ is helpful in these cases. Cytotoxic markers are always expressed (T-cell intracellular antigen (TIA)-1, granzyme B, perforin), but CD56 is negative [3]. Staining for CD30 is consistently negative in true subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Proliferation markers (i.e., Ki-67) highlight a characteristic pattern of proliferating cells arranged in small clusters and around the adipocytes (Fig. 5.9c).

EBV has been detected only in very rare cases of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma [35]. I have observed EBER-1-positive cells only in one case, which had otherwise conventional clinicopathologic features of the disease (Fig. 5.10). In cases positive for EBV, the presence of an immunodeficiency (iatrogenic or non-iatrogenic) should be investigated.

Molecular Genetics

Molecular analysis of the TCR genes shows a monoclonal rearrangement in the majority of cases [1]. Single-cell comparative genomic hybridization of laser-microdissected specimens revealed gains of chromosomes 2q and 4q and losses of chromosomes 1pter, 2pter, 10qter, 11qter, 12qter, 16, 19, 20, and 22 [36]. In the same study, allelic NAV3 aberrations were found by loss of heterozygosity and fluorescence in situ hybridization analyses in almost half of the cases [36]. It should be underlined that these results have been obtained in nine patients only, so their value has to be confirmed.

Differential Diagnosis with Other Cutaneous NK/T-Cell Lymphomas with Prominent Involvement of the Subcutaneous Tissue

Rare cases of mycosis fungoides presenting with subcutaneous lesions can only be excluded by an accurate clinical history and by clinicopathologic correlation. In addition, mycosis fungoides usually shows a CD4+ phenotype, in contrast to the CD8+ one of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (but a CD8+ phenotype may be encountered in cases of mycosis fungoides). Examination of more than one skin biopsy usually is sufficient for a precise classification, as purely subcutaneous infiltration is only an occasional finding in mycosis fungoides.

The following features favor a diagnosis of cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma: involvement of the dermis and/or epidermis (often with marked epidermotropism) in the same biopsy or in sequential biopsies taken at the same time or over time; negativity for α/β and positivity for γ/δ T-cell markers; and positivity for CD56.

Features that favor the diagnosis of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, are: marked involvement of the dermis, more rarely also of the epidermis in the same biopsy or in sequential biopsies taken at the same time or over time; NK-cell phenotype; positivity for CD56; positive signal for EBV upon in situ hybridization; and lack of monoclonal rearrangement of the TCR genes.

Finally, features that favor a subcutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma include the presence of large pleomorphic or anaplastic cells strongly positive for CD30 and for CD4. It should be underlined, however, that purely subcutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphomas are exceedingly rare and that CD30 expression may be observed in neoplastic cells of other T- and B-cell lymphomas, thus implying that such a diagnosis should be made only upon compelling evidence and after careful exclusion of other lymphoproliferative disorders.

Differential Diagnosis with Lupus Panniculitis

As mentioned before, I have come across cases of genuine lupus erythematosus associated with subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, so evidence of one disease cannot be used to rule out the presence of the second. Clinically, both lupus panniculitis and subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma present with panniculitic lesions located mostly on the limbs, thus not allowing a differential diagnosis. Histology also shows more overlapping than distinguishing features (particularly in later lesions!), and necrosis and degenerative changes may be prominent in both diseases. A subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma with prominent lesional atrophy, mimicking the clinical features of lupus panniculitis, was published as a teaching case in the last edition of this book [37]. Plasma cells are often present within the inflammatory infiltrate in lupus panniculitis but not in subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (with the possible exception of some pediatric cases [26]). Another distinguishing feature is the presence in lupus panniculitis of nodular aggregates of B-cells, sometimes forming small germinal centers, characteristically located at the periphery of the fat lobules. I have never encountered similar aggregates in cases of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. CD3+/CD8+ cells are the hallmark of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma and may be observed in lupus panniculitis as well, but the proliferation rate is lower in the latter. Useful criteria for differential diagnosis are represented also by the finding in subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma of rimming of lymphocytes that are positive for Ki67 and in lupus panniculitis of clusters of plasmacytoid dendritic cells positive for CD123 [38]. Finally, evidence of a clonal rearrangement of the TCR genes strongly supports a diagnosis of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.

Association of Subcutaneous Panniculitis-Like T-Cell Lymphoma and Lupus Panniculitis

Although in most instances lupus panniculitis and subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma can be differentiated according to the criteria just mentioned, I have rarely observed biopsies where typical features of both diseases could be observed in different areas of one and the same specimen (Fig. 5.11). These cases represent a conceptual as well as a practical problem, since besides diagnostic difficulties they raise the question as to whether the two diseases may be indeed related. Patients with lupus erythematosus are at higher risk of developing hematologic malignancies, but these are mostly of B-cell lineage, and the true risk of developing subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma is currently unclear. Cases with features of both diseases, on the other hand, may suggest that a relationship exists and that in some cases subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma may evolve out of the background of a lupus panniculitis. In this context, about 20% of patients with subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma have a history of autoimmune disorders, particularly lupus erythematosus [3]. It must be underlined that at the present state of knowledge this can only be considered as a hypothesis, and further studies should elucidate the interplay between the two conditions. It must also be mentioned that there is no need to perform staging investigations in patients with lupus panniculitis or to treat them differently than is usually done.

Treatment

The evaluation of different treatment schemes reported in the literature reflects the confusion concerning the classification of the disease in older publications. In fact, extremely aggressive treatment modalities mentioned in some publications are not necessary for cases of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma as defined in this chapter and in modern classification schemes. Many patients can be controlled for long periods of time with systemic steroids [3, 11]. Combinations of steroids with cyclosporine or methotrexate, or cyclosporine alone, have also been used [39–41]. Systemic chemotherapy (CHOP or other schemes) and radiotherapy have been used in many instances, but should probably be left for recalcitrant lesions that do not respond to less aggressive treatments [3, 9]. Complete remission has been achieved in one of two children treated by cyclosporine followed by chemotherapy [25].

Some reports have highlighted the efficacy of autologous or allogeneic bone marrow/stem cell transplantation [42–45]. Such an aggressive therapeutic option should be considered only for the management of patients with progressive disease and extracutaneous involvement.

Prognosis

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma is an indolent lymphoma with good prognosis and a 5-year overall survival of over 80% [3, 23]. The onset of a hemophagocytic syndrome is a bad prognostic sign [3] and angiotropism has been recognized as a bad prognostic marker in one Chinese study [46].

Once again, it should be remembered that exact appreciation of the prognosis of cases reported in the past as “subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma” is hindered by the lack of proper phenotypic investigations and by the inclusion in the group of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma of cases that in modern classifications would be placed in different categories.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree