Viral Diseases of Skin and Mucosa

Viral infections of skin and mucosa produce a wide spectrum of local and systemic manifestations.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Etiology. MCV with four discrete viral subtypes, I, II, III, IV. 30% homology with smallpox virus. The virus has not been cultured. Not distinguishable from other poxviruses by electron microscopy. MCV colonizes the epidermis and infundibulum of hair follicle. Transmitted by skin-to-skin contact.

Demography. More common in children and sexually active adults; males >females. In advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, hundreds of small mollusca or giant mollusca occur on the face and other sites. Pathogenesis. A subclinical carrier state of MCV probably exists in many healthy adults. Unique among poxviruses, MCV infection results in epidermal tumor formation; other human poxviruses cause a necrotic “pox” lesion. Rupture and discharge of the infectious viruspacked cells occur in the umbilication/crater of the lesion.

Clinical Manifestation

Papules, nodules, tumors with central umbilication or depression (Figs. 27-1–27-4). Skin-colored. Round, oval, hemispherical. Isolated single lesion; multiple, scattered discrete lesions; or confluent mosaic plaques. Larger mollusca may have a central keratotic plug, which gives the lesion a central dimple or umbilication. Gentle pressure on a molluscum extrudes the central plug.

Figure 27-1. Molluscum contagiosum Typical umbilicated papules. Discrete, solid, skincolored papules 3–5 mm on the chest of an adolescent female. The lesion with red halo is regressing spontaneously.

Autoinoculation is apparent in that mollusca are clustered at a site such as the axilla (Fig. 27-2).

Host immune response to viral antigen results in an inflammatory halo around mollusca (Fig. 27-2) and heralds spontaneous regression.

Figure 27-2. Molluscum contagiosum: axilla Multiple, small pink papules in the axilla of a healthy child. The erythema surrounding the lesions represents an inflammatory response to MC and usually indicates the lesions are regressing.

Host defense defects MC can be extensive with immunosuppressive therapy and HIV disease (Figs. 27-3 and 27-4).

Figure 27-3. Molluscum contagiosum: penis Multiple, small shiny papules on penile shaft.

Figure 27-4. Molluscum contagiosum: face A 52-year-old male with HIV disease. Discrete and confluent umbilicated papules on the face.

In individuals with darker skin, significant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur after treatment or spontaneous regression. Distribution. Any site may be infected, especially naturally occluded sites, i.e., axillae, antecubital, popliteal fossae, anogenital folds. Autoinoculation spreads lesions. Mollusca may be widespread in areas of atopic dermatitis. In adults with sexually transmitted mollusca: groins, genitalia, thighs, and lower abdomen. Multiple facial mollusca (Fig. 27-4) suggest host defense defect. Mollusca can occur in the conjunctiva, causing a unilateral conjunctivitis.

Differential Diagnosis

Multiple Small Papules. Flat warts, condylomata acuminata, syringoma, sebaceous hyperplasia.

Large Solitary Molluscum. Keratoacanthoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), basal cell carcinoma, epidermal inclusion cyst.

Multiple Facial Mollusca in HIV Disease. Disseminated invasive fungal infection, i.e., cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and penicilliosis (see Appendix C).

Laboratory Findings

Dermatopathology. Epidermal cells contain large intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, i.e., molluscum bodies that appear as single, ovoid eosinophilic structures in lower cells of stratum malpighii. Infection also occurs in epidermis and superficial hair follicle. Molluscum bodies can also be seen on smears of keratin extruded from the center of a lesion.

Diagnosis

Usually made on clinical findings. Biopsy lesion in HIV disease if disseminated invasive fungal infection is in the differential diagnosis.

Course

In the normal host, mollusca often persist up to 6 months and then undergo spontaneous regression without scarring. In HIV disease, mollusca persist and proliferate even after aggressive local therapy. Mollusca are usually symptomatic, and can cause cosmetic disfigurement and concern about transmission of mollusca to a sexual partner.

Treatment

Office-based treatments include curettage, cryosurgery, and electrodessication. Imiquimod 5% cream may be effective.

Clinical Manifestation

Macules, Papules, Nodules at Site of Inoculation. Most commonly occur on hands, arms, legs, and face (Figs. 27-5 and 27-6). Lesions may appear edematous or bullous. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) or target lesions occur. Color is pink to red to blanched. Lesions evolve to crusted erosions or ulcers. Healing occurs spontaneously in 4–6 weeks without scarring.

Figure 27-5. Human orf: multiple lesions on hands Multiple blisters with target/IRIS patterns in lesions on the hands of a sheep herder.

Figure 27-6. Human orf: finger A 19-year-old male of Greek heritage; lesions appeared 10 days after Greek Easter and was associated with slaughter of a lamb for the Easter feast.

Other Findings. Ascending lymphangitis and lymphadenopathy. More extensive infection may occur with host defense defects.

Differential Diagnosis

Impetigo, furuncles, milker’s nodules.

Diagnosis

Clinical findings with the appropriate history. Can be confirmed by detection of orf virus DNA by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

Course

Resolves spontaneously in 4–6 weeks, healing without scar formation. Erythema multiformelike eruptions (see Section 14) have been reported in human orf. Widespread lesions spread by autoinoculation may occur in atopic dermatitis. In humans, lasting immunity is conferred by infection.

Treatment

No effective antiviral treatment. Treat bacterial secondary infection.

Clinical Manifestation

Solitary or multiple red-purple nodules (Fig. 27-7) occur at site of inoculation. Usually on exposed sites such as hands; may occur in burn wounds.

Figure 27-7. Milker’s nodule: finger A single beefy eroded nodule on the finger of a dairy farmer at the site of inoculation.

Other Findings. Lymphadenopathy.

Differential Diagnosis

Orf, furuncle, herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, pyogenic granuloma.

Diagnosis

Usually made on history of bovine exposure and clinical findings.

Course

Resolves spontaneously.

Treatment

No effective antiviral treatment. Treat bacterial secondary infection.

Etiology and Epidemiology

The last cases of endemic smallpox occurred in 1977. Eradication declared in 1980. Smallpox estimated to have killed 300–500 persons during the 20th century. Persons in the general population in the United States under age 30 have not been vaccinated.

Etiology. Variola major and Variola Minor. Humans are the only host of variola. DNA virus that replicates in cell cytoplasm. Transmitted by respiratory-droplets or fomites.

Classification. Variola Major. 90% of cases. 30% mortality.

Variola Minor or Alastrim. 2% of cases in unvaccinated persons and 25% of vaccinated persons. Variola Sine Eruptione. Occurs in vaccinated persons and infants with maternal antibodies. Smallpox with Flat Lesions. Case fatality 97% among unvaccinated persons.

Hemorrhagic smallpox. Near 100% case fatality rate.

Pathogenesis. Enters the respiratory tract, seeding mucous membranes, passing rapidly into local lymph nodes. Mouth/pharynx is infected during viremia. Virus invades capillary endothelium of dermis, resulting in skin lesions. Virus is abundant in skin and oropharyngeal lesions in early illness. Death ascribed to toxemia, associated with immune complexes, and to hypotension. Infection with smallpox confers lifelong immunity.

Clinical Manifestation

Small red macules evolve to papules over 1–2 days. Initial lesions on face and extremities, then gradually become disseminated. In 1–2 more days, papules become vesicles. Vesicles evolve to pustules 4–7 days after onset of rash (Figs. 27-8), and last for 5–8 days. Followed by umbilication and crusting (Fig. 27-8C). Lesions are generally all at the same stage of development. Pockmarks/pitted scars occur in 65–85% of severe cases, especially on the face (Fig. 27-9). Secondary Staphylococcus aureus infection with abscesses and cellulitis may occur in smallpox lesions.

Figure 27-8. Smallpox: variola major Multiple pustules becoming confluent on the face.

Figure 27-9. Smallpox: scarring on face A 50-year-old Indian male with a history of smallpox as a child has multiple depressed scars on face 40 years after smallpox infection. (Courtesy of Atul Taneja, MD.)

Mucous Membranes. Enanthema (tongue, mouth, oropharynx) precedes exanthem by a day.

General Findings. Variants: Panophthalmitis, keratitis, secondary infection of eye (1%). Arthritis in children (2%). Encephalitis (<1%)

Differential Diagnosis

Severe chicken pox (varicella lesions are in different stages of development), measles, secondary syphilis (great pox), hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) (coxsackievirus A-16), cowpox, monkeypox, tanapox.

Diagnosis

A febrile illness with acute onset of fever >38.3°C (101°F) followed by exanthem characterized by firm, deep-seated vesicles or pustules in the same stage of development without other apparent cause (see http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/diagnosis/casedefinition.asp).

Treatment

Report possible smallpox to public health officials; diagnosis confirmed in a Biological Safety Level 4 laboratory where staff members have been vaccinated. Cidofovir may be effective.

Clinical Manifestation

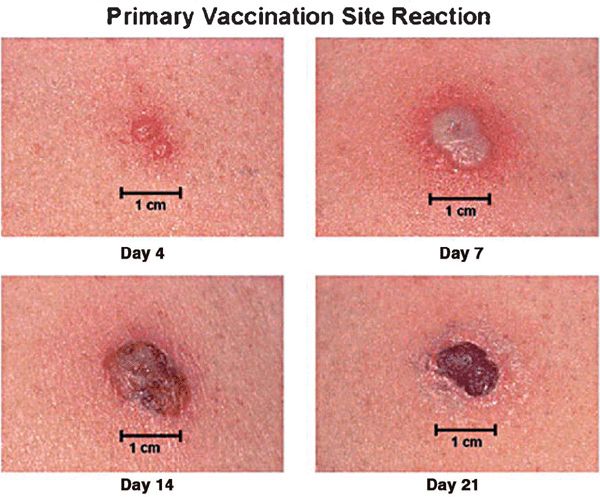

Normal Vaccination Reaction. (Fig. 27-10)

Figure 27-10. Primary smallpox vaccination site reaction Expected vaccine site reaction and progression following primary smallpox vaccination or revaccination after a prolonged period between vaccinations. Multiple pressure vaccination technique used.

• 6-8 days after vaccination, loculated pustule (Jennerian pustule) 1-2 cm in diameter develops at site.

• Central crusting begins and spreads peripherally over 3–5 days.

• Local edema and a dark crust remain until the third week.

• Other reactions are classified as equivocal, and another vaccination is required. Local “satellite” pustules may occur.

Reactions and Complications

Noninfectious Rashes. Erythema multiformelike.

Macular (“Toxic Eruption”). Maculopapular; vesicular. Urticarial. Most common 7–14 days after primary vaccination or earlier after revaccination.

Noninfectious. Immune-mediated encephalitis, pericarditis, myocarditis.

Bacterial Infection. S. aureus and group A streptococcus can cause enlarging crusted inoculation site (impetigo or soft tissue infection). Tetanus.

Accidental inoculation to normal or abnormal skin such as atopic dermatitis (eczema vaccinatum).

Congenital Vaccinia. Vaccination during pregnancy may result in dissemination of infection to fetus.

Generalized Vaccinia. Generalized vesicular/pustular reaction. Self-limited, usually occurring in one crop. Usually occurs in a healthy individual whose antivaccinal antibody response is delayed but adequate. Almost always benign, with normal-healing primary vaccination. May become malignant with progression (see below).

Progressive Vaccinia. Vaccination site fails to heal and continues to enlarge forming an ulcer with raised edges. Relentless outward spread of infection from vaccination site and eventual dissemination to other areas of the body.

Diagnosis

Clinical history, physical examination, and clinical course. Persistence of virus can be confirmed by culturing vaccinia virus from the skin lesions.

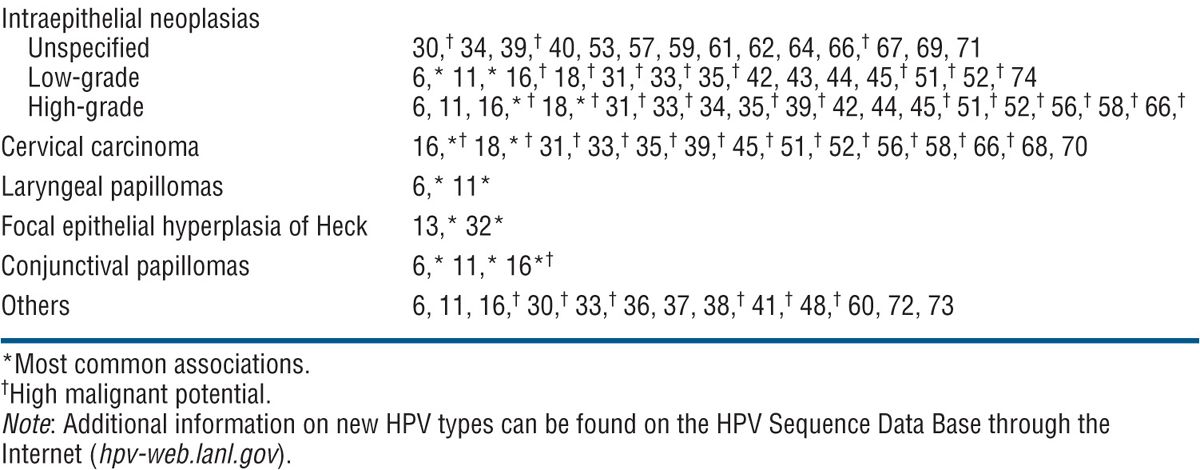

TABLE 27-1 CORRELATION OF HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS TYPE WITH DISEASE

Etiology

Papillomaviruses are double-stranded DNA viruses of the papovavirus class, which infect most vertebrate species with exclusive host and tissue specificity. Infections are restricted squamous epithelia of skin and mucous membranes. Clinical lesions induced by HPV and their natural history are largely determined by HPV type. HPV are normally grouped according to their pathologic associations and tissue specificity—either cutaneous or mucosal. Mucosal-associated HPV can be further subgrouped according to their risk of malignant transformation. New types of HPV are defined as possessing <90% homology to known types in six specified early and late genes.

Epidemiology

Transmission. Skin-to-skin contact. Minor trauma with breaks in stratum corneum facilitates epidermal infection.

Demography. Host defense defects are associated with an increased incidence of and more widespread cutaneous warts: HIV disease, iatrogenic immunosuppression with solid organ transplantation.

Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis. Autosomal-recessive hereditary disorder. Acquired EDV-like lesions seen in HIV disease.

Clinical Manifestation

Common Wart or Verruca Vulgaris

Firm papules, 1–10 mm or larger (Figs. 27-11–27-15), hyperkeratotic, clefted surface, with vegetations. Isolated lesion, scattered discrete lesions. Occur at sites of trauma: hands, fingers, and knees. Palmar lesions disrupt the normal line of fingerprints. Return of fingerprints is a sign of resolution of the wart. Characteristic “red or brown dots,” best visualized with dermatoscope, are pathognomonic, representing thrombosed dermal papilla capillary loops.

Figure 27-11. Verruca vulgaris on face A 3-year-old boy with common wart on the moustache area.

Figure 27-12. Verruca vulgaris: thumb A 25-year-old male with hyperkeratotic, verrucous papules on the dorsal thumb. The dark points represent thrombosed capillaries. The lesion resolved with electrodessication, having failed to respond to cryosurgery.

Figure 27-13. Verruca vulgaris: hands A 20-year-old immunosuppressed male with nephrotic syndrome. Multiple verrucae on the (A) dorsum and (B) palm of the hand.

Figure 27-14. Periungual warts A 77-year-old male with extensive periungual warts. He was depressed and picked at periungual skin folds created portal of entry for HPV. Lesions resolved with hyperthermia.

Figure 27-15. Giant warts on hand and forearm. A 51-year-old female with recalcitrant warts on hands for 2 years. Immunodeficiency was suspected but not detected.

Linear arrangement: inoculation by scratching.

Annular warts: at sites of prior therapy.

Butcher’s warts: large cauliflower-like lesions on hands of meat handlers.

Filiform warts have relatively small bases, extending out with elongated cap (Fig. 27-11).

Plantar Warts (Verruca Plantaris)

Early small, shiny, sharply marginated papule (Fig. 27-16) → plaque with rough hyper-keratotic surface, studded with brown-black dots (thrombosed capillaries). As with palmar warts, normal dermatoglyphics are disrupted. Return of dermatoglyphics is a sign of resolution of the wart. Warts heal without scarring. Therapies such as cryosurgery and electrosurgery can result in scarring at treatment sites. Tenderness may be marked, especially in certain acute types and in lesions over sites of pressure (metatarsal head).

Figure 27-16. Verruca plantaris: plantar feet A 71-year-old male with chronic lymphatic leukemia. Large and painful on pressure, warts are seen on the plantar feet and toes. Multiple warts were also present on the fingers. After many failed therapeutic modalities, he was successfully treated with electron beam radiation.

Mosaic warts: Confluence of many small warts. “Kissing” warts: lesion may occur on opposing surface of two toes (Fig. 27-17). Plantar foot, often solitary but may be three to six or more. Pressure points, heads of metatarsal, heels, toes.

Figure 27-17. Extensive verrucae A 49-year-old male with HIV disease has confluent warts on the hands and feet. The large warts on opposing toes are referred to as “kissing warts.”

Flat Warts (Verruca Plana)

Sharply defined, flat papules (1–5 mm); “flat” surface; the thickness of the lesion is 1–2 mm (Fig. 27-18). Skin-colored or light brown. Round, oval, polygonal, linear lesions (inoculation of virus by scratching). Occur on face, beard area (Fig. 27-19), dorsa of hands, and shins.

Figure 27-18. Verruca plana A 12-year-old male kidney transplant recipient. Multiple brown keratotic papules are seen on the forehead and scalp.

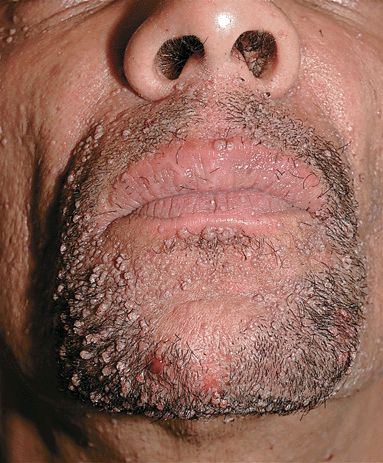

Figure 27-19. Filiform and flat warts A 38-year-old male with HIV disease has a confluence of lesions on face and beard area. Lesions resolved after successful antiretroviral therapy.

Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

Autosomal-recessive condition. Flat-topped papules. Tinea versicolor-like lesions, particularly on the trunk. Color: skin-colored, light brown, pink, hypopigmented. Lesions may be numerous, large, and confluent. Seborrheic keratosis-like and actinic keratosis-like lesions. Linear arrangement after traumatic inoculation. Distribution: face, dorsa of hands, arms, legs, anterior trunk (Fig. 27-20). Premalignant and malignant lesions arise most commonly on face. SCC: in situ and invasive.

Figure 27-20. EDV-like flat warts on chest A 44-year-old male with HIV disease had extensive flat wart-like lesions on face, neck, trunk, abdomen.

Host Defense Defects

(HIV disease, iatrogenic immunosuppression). HPV-induced warts are common (Fig. 27-21) and may be difficult to treat successfully. Some have atypical histologic features and may progress to in situ and invasive SCC.

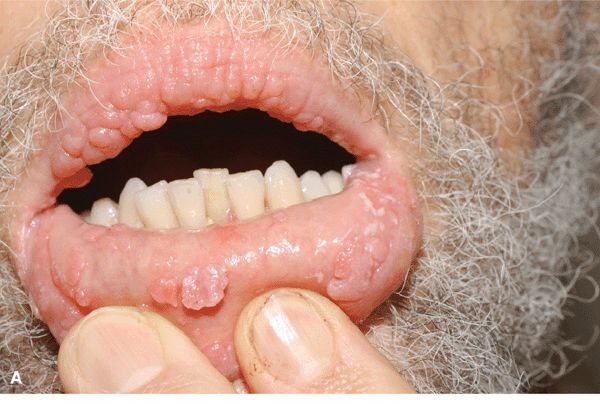

Figure 27-21. Multiple oral condylomata in HIV disease. Lesions resolved with antiretroviral therapy.

Human Papillomavirus: Oropharyngeal Diseases

HPV infects mucosal epithelial cells of the mouth, nose, and airways (Fig. 27-21). Oral infections may be subclinical or cause benign or malignant oral neoplasms. In respiratory or laryngeal papillomatosis, HPV 6 and 11 are acquired during vaginal delivery and cause warts of the oropharynx and upper airways. Laryngeal lesions cause major morbidity. SCC occurs in some persons.

Human Papillomavirus: Anogenital Infections

See Section 30, “Sexually Transmitted Diseases.”

Differential Diagnosis

Verruca vulgaris molluscum contagiosum, seborrheic keratosis, actinic keratosis, keratoacanthoma, SCCIS, invasive SCC.

• Verruca plantaris callus, corn or keratosis, exostosis.

• Verruca plana, syringoma (facial), molluscum contagiosum.

• Epidermodysplasia verruciformis pityriasis versicolor, actinic keratoses, seborrheic keratoses, SCCIS, basal cell carcinoma.

Laboratory Findings

Dermatopathology. Acanthosis, papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis. Characteristic feature is foci of vacuolated cells (koilocytosis), vertical tiers of parakeratotic cells, and foci of clumped keratohyaline granules.

Diagnosis. Usually made on clinical findings. With host defense defects, HPV-induced SCC at periungual sites or anogenital region should be ruled out by lesional biopsy.

Course

In immunocompetent individuals, cutaneous HPV infections usually resolve spontaneously, without therapeutic intervention. With host defense defects, cutaneous HPV infections may be very resistant to all modalities of therapy. With EDV, lesions first occur at 5–7 years of age and increase in numbers progressively, becoming widespread in some. About 30–50% of individuals with EDV develop malignant cutaneous lesions on areas of skin exposed to sunlight.

Treatment

Goal. Aggressive therapies, which are often quite painful and may be followed by scarring, are usually to be avoided because the natural history of cutaneous HPV infections is for spontaneous resolution in months or a few years. Plantar warts that are painful because of their location warrant more aggressive therapies. Patient-Initiated Therapy. Minimal cost; no/minimal pain.

For Small Lesions. 10–20% salicylic acid and lactic acid in collodion.

For Large Lesions. 40% salicylic acid plaster for 1 week, then application of salicylic acid–lactic acid in collodion.

Imiquimod Cream. At sites that are not thickly keratinized, apply half-strength three times per week. Persistent warts may require occlusion. Hyperkeratotic lesions on palms/soles should be debrided frequently; Imiquimod used alternately with a topical retinoid such as tazarotene topical gel may be effective.

Hyperthermia for Verruca Plantaris. Hyperthermia with hot water [45°C (113°F)] immersion for 20 minutes or three times weekly for up to 16 treatments is effective in some patients.

Clinician-Initiated Therapy. Costly, painful.

Cryosurgery. If patients have tried home therapies and liquid nitrogen is available, light cryo-surgery using a cotton-tipped applicator or cryospray, freezing the wart and 1–2 mm of surrounding normal tissue for approximately 30 seconds, is quite effective. Freezing kills the infected tissue but not HPV.

Cryosurgery is usually repeated about every 4 weeks until the warts have disappeared. Painful.

Electrosurgery. More effective than cryosurgery, but also associated with a greater chance of scarring. EMLA cream can be used for anesthesia for flat warts. Lidocaine injection is usually required for thicker warts, especially palmar/plantar lesions.

CO2 Laser Surgery. May be effective for recalcitrant warts, but no better than cryosurgery or electrosurgery in the hands of an experienced clinician.

Surgery. Single, nonplantar verruca vulgaris: curettage after freon freezing; surgical excision of cutaneous HPV infections is not indicated in that these lesions are epidermal infections.

Etiology and Epidemiology

RNA Viruses. Picornaviridae: Poliovirus, coxsackieviruses, echovirus, enterovirus, hepatitis A virus, rhinovirus. Togaviridae: Rubella virus, attenuated rubella virus in vaccine. Flaviviridae: Dengue, hepatitis C virus. Paramyxoviridae: measles, mumps. Orthomyxoviridae: influenza A, B, and C viruses. Retroviridae: Human T-lymphotrophic virus types I and II, HIV types 1 and 2 (acute HIV syndrome). DNA Viruses. Parvoviridae: Parvovirus B19 (erythema infectiosum). Hepadnaviridae hepatitis B virus. Adenoviridae. Herpesviridae: HSV types 1 and 2, varicella zoster virus (VZV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), HHV 6 and 7 (exanthem subitum, roseola infantum), Kaposi sarcoma (KS)-associated virus (HHV-8). Poxviridae: Variola (smallpox) virus, orf virus, and MCV. Bacteria. Group A streptococcus: scarlet fever, toxic shock syndrome. S. aureus: toxic shock syndrome. Legionella, Leptospira, Listeria, Meningococci, Treponema pallidum. Mycoplasmal Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Rickettsiae Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Tick-borne spotted fevers. Rickettsialpox. Murine typhus. Epidemic typhus

Miscellaneous Strongyloides, Toxoplasma.

Pathogenesis. Skin lesions may be produced by the following:

• Direct effect of microbial replication in infected cells.

• Host response to the microbe.

• Interaction of these two phenomena.

Clinical Manifestation

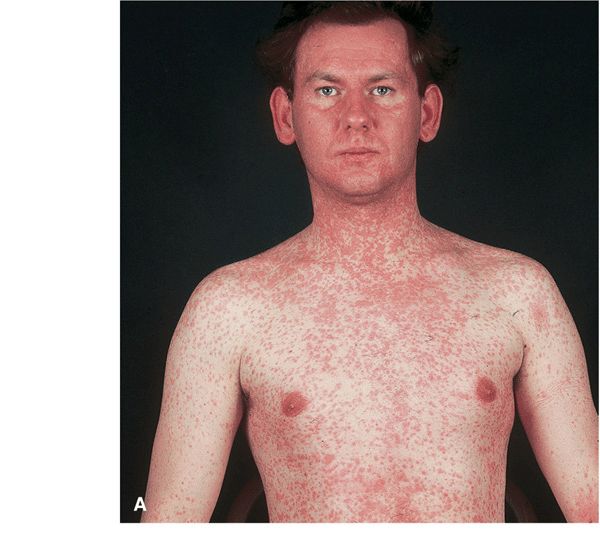

Prodrome. Acute infection syndrome: Fever, malaise, coryza, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and headache. Exanthematous Eruption. Resembles the exanthem occurring with measles or morbilli, i.e., measles-like or “morbilliform.” Also referred to as maculopapular. Characterized by initially discrete, often becoming confluent pink macules and papules (Fig. 27-22). Usually central, i.e., head, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities. Most often progresses centrifugally. Lesions can become hemorrhagic with petechiae, hemorrhagic measles.

Figure 27-22. Measles-like exanthema Disseminated erythematous macules and papules, typical of the cutaneous changes with many viral infections. Differential diagnosis of an exanthematous or morbilliform adverse cutaneous drug eruption. (A) Typical distribution of lesions on the trunk and extremities. (B) Closeup of pink macules and papules becoming confluent in some areas.

Scarlatiniform Eruption. Diffuse erythema.

Vesicular Eruptions. Initially, vesicles with clear fluid. May evolve to pustules. In a few days to a week, roof of vesicle sloughs, resulting in erosions. In varicella, lesions are disseminated and may involve oropharynx. In hand foot and mouth disease, vesicles/erosion occur in oropharynx; painful linear vesicles on palms/soles.

Oropharyngeal Lesions. Enanthem. Koplik spots in measles. Petechiae on soft palate (Forchheimer sign). Microulcerative lesions in herpangina due to coxsackievirus A (Fig. 27-27). Palatal petechiae in mononucleosis syndrome of primary EBV or CMV infection. Aphthous ulcer-like lesions occur with primary HIV infection.

Conjunctivitis. Occurs with measles.

Genitalia. External aphthous ulcer-like lesion with primary HIV infection.

Systemic Findings. Lymphadenopathy. Hepatomegaly. Splenomegaly.

Differential Diagnosis

Adverse cutaneous drug eruption (ACDE), systemic lupus erythematosus, Kawasaki syndrome.

Diagnosis

Usually made on history and clinical findings. Serology: Acute and convalescent titers most helpful in specific diagnosis. Cultures: If practical.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Etiology. Rubella virus, an RNA togavirus, member of Rubivirus genus. Attenuated rubella virus used in immunization can cause an illness with rubella-like rash, lymphadenopathy, and arthritis.

Demography. Before widespread immunization, most commonly occurred in children <15 years. Currently young adults. Risk factors: Lack of active immunization and lack of natural infection. After immunization began in 1969, incidence decreased by 99% in industrialized countries.

Transmission. Inhalation of aerosolized respiratory droplets. Moderately contagious. 10–40% of cases asymptomatic. Period of infectivity from end of incubation period to disappearance of rash.

Clinical Manifestation

Prodrome. Prodrome usually absent, especially in young children. In adolescents and young adults: anorexia, malaise, conjunctivitis, headache, low-grade fever, and mild upper respiratory tract symptoms. In women, rubella-like illness frequently follows administration of attenuated live rubella virus with arthralgias.

Exanthem. Pink macules, papules (Fig. 27-23). Initially on forehead, spreading inferiorly to face, trunk, and extremities during first day. By second day, facial exanthem fades. By third day, exanthem fades completely without residual pigmentary change or scaling. Truncal lesions may become confluent, creating a scarlatiniform eruption.

Figure 27-23. Rubella A 21-year-old male. Erythematous macules and papules appearing initially on the face and spreading inferiorly and centrifugally to the trunk and extremities, usually within the first 24 hours. Postauricular and posterior cervical lymph nodes were enlarged. Lesions becoming confluent on the cheeks while clearing on the forehead. Truncal lesions appear 24 hours after onset of facial lesions.

Mucous Membranes. Petechiae on soft palate (Forchheimer sign) during prodrome (also seen in infectious mononucleosis).

Lymph Nodes. Enlarged during prodrome. Postauricular, suboccipital, and posterior cervical lymph nodes enlarged and possibly tender. Mild generalized lymphadenopathy may occur. Enlargement usually persists for 1 week but may last for months.

Spleen. May be enlarged.

Joints. Arthritis in adults; possible effusion. Arthralgia, especially in adult women after immunization.

Congenital Rubella Syndrome. Congenital heart defects; cataracts; microphthalmia, microcephaly, hydrocephaly, deafness.

Differential Diagnosis

Exanthem. Other viral exanthems, ACDE, and scarlet fever.

Exanthem with Arthritis. Acute rheumatic fever, rheumatoid arthritis, erythema infectiosum.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis; can be confirmed by serology. Virus can be isolated from throat, joint fluid aspirate.

Course

In most persons, rubella is a mild, inconsequential illness. However, when rubella occurs in a pregnant woman during the first trimester, the infection can be passed transplacentally to the developing fetus. Approximately half of infants who acquire rubella during the first trimester of intrauterine life will show clinical signs of damage from the virus.

Treatment

Rubella is preventable by immunization. Previous rubella should be documented in young women: if antirubella antibody titers are negative, rubella immunization should be given.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Etiology. Measles virus, member of RNA genus Morbillivirus and family Paramyxoviridae.

Demography. Measles is no longer endemic in United States, Europe, Canada, and Japan; cases result from importation of measles. Hyperendemic in many developing nations, resulting in 164,000 deaths in 2008.

Risk Factors. Current outbreaks in the United States occur in inner city unimmunized preschool-age children, school-age persons immunized at an early age, and imported cases.

Transmission spread by respiratory droplet aerosols produced by sneezing and coughing. Infected persons contagious from several days before onset of rash up to 5 days after lesions appear. Attack rate for susceptible contacts >90–100%. Asymptomatic infection uncommon.

Pathogenesis. Virus enters cells of respiratory tract, replicates locally, spreads to regional lymph nodes, and disseminates hematogenously to skin and mucous membranes, where it replicated. Modified measles, a milder form of the illness, may occur in individuals with preexisting partial immunity induced by active or passive immunization. Persons deficient in cellular immunity are at high risk for severe measles.

Clinical Manifestation

Incubation Period. 10–15 days.

Prodrome. Fever. Malaise. Upper respiratory symptoms (coryza, hacking bark-like cough). Photophobia, conjunctivitis with lacrimation. Periorbital edema. As exanthem progresses, systemic symptoms subside.

Exanthem. On the fourth febrile day, erythematous macules and papules appear on forehead at hairline, behind ears; spread centrifugally and inferiorly to involve the face, trunk (Fig. 27-24), extremities, palms/soles, reaching the feet by third day. Initial discrete lesions may become confluent, especially on face, neck, and shoulders. Lesions gradually fade in order of appearance, with subsequent residual yellowtan stain or faint desquamation. Exanthem resolves in 4–6 days.

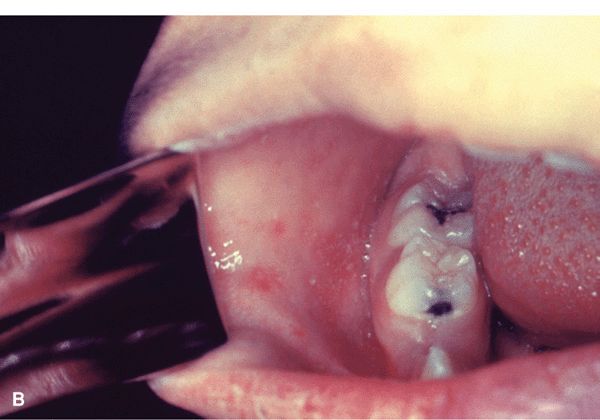

Figure 27-24. Measles with exanthem (A) Erythematous macule, first appearing on the face and neck where they become confluent, spreading to the trunk and arms in 2–3 days where they remain discrete. In contrast, rubella also first appears initially on the face but spreads to the trunk in 1 day. Koplik spots on the buccal mucosa were also present. Erythematous papules have become confluent on the face on the fourth day.

Measles with Koplik spots (B) Red papules on buccal mucosa opposite premolars prior of appearance of exanthema. (From the CDC.)

Enanthem. Cluster of tiny bluish-white spots on red background, appearing on or after second day of febrile illness, are seen on buccal mucosa opposite premolar teeth, i.e., Koplik spots that are pathognomonic of measles. Appear before exanthem. Also: entire buccal/inner labial mucosa may be inflamed.

Bulbar Conjunctivae. Conjunctivitis, injected, red.

General Examination. Generalized lymphadenopathy. Diarrhea, vomiting. Splenomegaly

Modified Measles. Milder clinical findings with preexisting partial immunity.

Atypical Measles. Occurs in individuals immunized with formalin-inactivated measles vaccine, subsequently exposed to measles virus. Exanthem begins peripherally and moves centrally; can be urticarial, maculopapular, hemorrhagic, and/or vesicular. Systemic symptoms can be severe.

Measles in Host With Defense Defects. Rash may not occur. Pneumonitis and encephalitis more common.

Differential Diagnosis

Disseminated Maculopapular Eruption. Morbilliform drug eruption, scarlet fever. Kawasaki syndrome.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis confirmed by serology. Multinucleated giant cells in secretions. Isolate virus from blood, urine, and pharyngeal secretions. Detect measles antigen in respiratory secretions by immunofluorescent staining. Detects genomic sequences of measles virus RNA in serum, throat swabs, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Course

Self-limited infection in most patients. Mortality rate in developing countries up to 10%. Age-specific rates of complications highest among children <5 years old and adults >20 years. Sites of complications: respiratory tract, central nervous system (CNS), tract. Complications more common in malnourished children, the unimmunized, and those with congenital immunodeficiency and leukemia. Acute complications (10% of cases): otitis media, pneumonia (bacterial or measles), diarrhea, measles encephalitis, and thrombocytopenia. Chronic complication: subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (Dawson encephalitis).

Treatment

Prophylactic immunization. Supportive care.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) and molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV) colonize the epidermis of most individuals without causing any clinical lesions. Benign epithelial proliferations such as warts and molluscum occur in some colonized persons, are transient, and eventually resolve without therapy. In immunocompromised individuals, however, these lesions may become extensive, persistent, and refractory to therapy.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) and molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV) colonize the epidermis of most individuals without causing any clinical lesions. Benign epithelial proliferations such as warts and molluscum occur in some colonized persons, are transient, and eventually resolve without therapy. In immunocompromised individuals, however, these lesions may become extensive, persistent, and refractory to therapy. Primary infections with many viruses cause acute systemic febrile illnesses and exanthems, are usually self-limited, and convey lifetime immunity. Smallpox caused severe morbidity and mortality, but no longer occurs because of worldwide immunization.

Primary infections with many viruses cause acute systemic febrile illnesses and exanthems, are usually self-limited, and convey lifetime immunity. Smallpox caused severe morbidity and mortality, but no longer occurs because of worldwide immunization. Eight human herpesviruses (HHV) often have asymptomatic primary infection but lifelong latent infection. With host defense defects, herpesviruses can become active and cause disease with significant morbidity and mortality.

Eight human herpesviruses (HHV) often have asymptomatic primary infection but lifelong latent infection. With host defense defects, herpesviruses can become active and cause disease with significant morbidity and mortality. Poxvirus family is a diverse group of epitheliotropic viruses that infect humans and animals. Only smallpox virus and MCV cause natural disease in humans. Smallpox virus causes systemic infection with exanthema, i.e., smallpox or variola. MCV causes localized skin lesions. Human orf and milker’s nodules are zoonoses that can occur in humans, given exposure to infected sheep or cattle. Other poxviruses zoonoses occurring in monkeys, cows, buffalo, sheep, and goats can also infect humans.

Poxvirus family is a diverse group of epitheliotropic viruses that infect humans and animals. Only smallpox virus and MCV cause natural disease in humans. Smallpox virus causes systemic infection with exanthema, i.e., smallpox or variola. MCV causes localized skin lesions. Human orf and milker’s nodules are zoonoses that can occur in humans, given exposure to infected sheep or cattle. Other poxviruses zoonoses occurring in monkeys, cows, buffalo, sheep, and goats can also infect humans. ICD-10: B08.1

ICD-10: B08.1

Molluscum contagiosum is a self-limited epidermal viral infection.

Molluscum contagiosum is a self-limited epidermal viral infection. Clinical Manifestation. Skin-colored papules; often umbilicated. Few to myriads of lesions. Host defense defects: large nodules with confluence.

Clinical Manifestation. Skin-colored papules; often umbilicated. Few to myriads of lesions. Host defense defects: large nodules with confluence. Course. In healthy persons, resolves spontaneously.

Course. In healthy persons, resolves spontaneously. ICD-10: B08.02

ICD-10: B08.02

Zoonosis. Caused by a dermatotropic parapoxvirus that commonly infects ungulates (sheep, goats, deer, etc.); it is transmitted to humans through contact with an infected animal or fomites. Most common in farmers, veterinarians, and sheep shearers. Only newborn animals lacking viral immunity are susceptible. Manifested as erythematous, exudative nodules around mouth that heal spontaneously, resulting in permanent immunity.

Zoonosis. Caused by a dermatotropic parapoxvirus that commonly infects ungulates (sheep, goats, deer, etc.); it is transmitted to humans through contact with an infected animal or fomites. Most common in farmers, veterinarians, and sheep shearers. Only newborn animals lacking viral immunity are susceptible. Manifested as erythematous, exudative nodules around mouth that heal spontaneously, resulting in permanent immunity. Transmission to Humans. Humans are infected by inoculation of virus by direct contact with lambs and indirectly by fomites. Human-to-human infection does not occur. Exposure occurs at the time of slaughter of lambs for Easter or the Muslim holiday Eid al-Adha.

Transmission to Humans. Humans are infected by inoculation of virus by direct contact with lambs and indirectly by fomites. Human-to-human infection does not occur. Exposure occurs at the time of slaughter of lambs for Easter or the Muslim holiday Eid al-Adha. ICD-10: B08.03

ICD-10: B08.03

Zoonosis parapoxvirus infection. Papular lesions occur on muzzles and oral cavity of calves and on teats of cows. Virus transmitted to humans by contact with bovine lesions or teat cups of milking machines; most common in dairy farmers. Clinical findings and course are similar to human orf.

Zoonosis parapoxvirus infection. Papular lesions occur on muzzles and oral cavity of calves and on teats of cows. Virus transmitted to humans by contact with bovine lesions or teat cups of milking machines; most common in dairy farmers. Clinical findings and course are similar to human orf. ICD-10: B03

ICD-10: B03

Smallpox is a viral infection unique to humans. The disease has been eradicated due to a global immunization program, last case having been reported in 1977.

Smallpox is a viral infection unique to humans. The disease has been eradicated due to a global immunization program, last case having been reported in 1977. ICD-10: B03

ICD-10: B03

Vaccinia virus is related to cowpox virus and is used for smallpox immunization (vaccination). Origin of the strains of vaccinia virus currently used for vaccination is unknown. Natural infection with cowpox virus confers immunity to smallpox. Prior vaccine (Dryvax) was made from vaccine virus cultured in the skin of calved. The current vaccine (ACAM2000) is made from vaccinia virus cultured in vitro on kidney epithelial cells.

Vaccinia virus is related to cowpox virus and is used for smallpox immunization (vaccination). Origin of the strains of vaccinia virus currently used for vaccination is unknown. Natural infection with cowpox virus confers immunity to smallpox. Prior vaccine (Dryvax) was made from vaccine virus cultured in the skin of calved. The current vaccine (ACAM2000) is made from vaccinia virus cultured in vitro on kidney epithelial cells. ICD-10: B97.7

ICD-10: B97.7 HPV are ubiquitous in humans, causing:

HPV are ubiquitous in humans, causing: Subclinical infection

Subclinical infection Wide variety of benign clinical lesions on skin and mucous membranes.

Wide variety of benign clinical lesions on skin and mucous membranes. Cutaneous and mucosal premalignancies (

Cutaneous and mucosal premalignancies ( More than 150 types of HPV have been identified and are associated with various clinical lesions and diseases. Papillomaviruses infect all mammalian species as well as birds, reptiles, and others.

More than 150 types of HPV have been identified and are associated with various clinical lesions and diseases. Papillomaviruses infect all mammalian species as well as birds, reptiles, and others. Cutaneous HPV infections occur commonly in the general population:

Cutaneous HPV infections occur commonly in the general population: Common warts: Represent approximately 70% of all cutaneous warts, occurring in up to 20% of all school-age children.

Common warts: Represent approximately 70% of all cutaneous warts, occurring in up to 20% of all school-age children. Butcher’s warts: Common in butchers, meat packers, fish handlers.

Butcher’s warts: Common in butchers, meat packers, fish handlers. Plantar warts: Common in older children and young adults, accounting for 30% of cutaneous warts.

Plantar warts: Common in older children and young adults, accounting for 30% of cutaneous warts. Flat warts: Occur in children and adults, accounting for 4% of cutaneous warts.

Flat warts: Occur in children and adults, accounting for 4% of cutaneous warts. Oncogenic HPV can cause SCCIS and invasive SCC with host defense defects.

Oncogenic HPV can cause SCCIS and invasive SCC with host defense defects. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV). Anogenital HPV infections.

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV). Anogenital HPV infections. External genital wart: most prevalent sexually transmitted infection (see

External genital wart: most prevalent sexually transmitted infection (see  Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Some HPV types have a major etiologic role in the pathogenesis of in situ as well as invasive SCC of the anogenital epithelium.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Some HPV types have a major etiologic role in the pathogenesis of in situ as well as invasive SCC of the anogenital epithelium. During delivery, maternal genital HPV infection can be transmitted to the neonate, resulting in anogenital warts and respiratory papillomatosis after aspiration of the virus into the upper respiratory tract.

During delivery, maternal genital HPV infection can be transmitted to the neonate, resulting in anogenital warts and respiratory papillomatosis after aspiration of the virus into the upper respiratory tract.

Certain human HPV types commonly infect keratinized skin.

Certain human HPV types commonly infect keratinized skin. Cutaneous warts are:

Cutaneous warts are: Discrete benign epithelial hyperplasia with varying degrees of surface hyperkeratosis.

Discrete benign epithelial hyperplasia with varying degrees of surface hyperkeratosis. Manifested as minute papules to large plaques.

Manifested as minute papules to large plaques. Lesions may become confluent, forming a mosaic.

Lesions may become confluent, forming a mosaic. The extent of lesions is determined by the immune status of the host.

The extent of lesions is determined by the immune status of the host.

Primary systemic infections often present with characteristic mucocutaneous rashes: exanthems and enanthems.

Primary systemic infections often present with characteristic mucocutaneous rashes: exanthems and enanthems. Exanthem and enanthem. An exanthem is eruptive rash associated with a systemic disorder; enanthem, mucosal lesions, associated with systemic disorder often associated with an exanthem. Often caused by viral agents but can also be associated with other infections: (bacterial, parasitic infections, sexually transmitted disease), adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs or toxin, and autoimmune disease.

Exanthem and enanthem. An exanthem is eruptive rash associated with a systemic disorder; enanthem, mucosal lesions, associated with systemic disorder often associated with an exanthem. Often caused by viral agents but can also be associated with other infections: (bacterial, parasitic infections, sexually transmitted disease), adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs or toxin, and autoimmune disease. ICD-10: B06

ICD-10: B06

Etiologic Agent. Rubella virus, an RNA togavirus.

Etiologic Agent. Rubella virus, an RNA togavirus. Clinical Manifestation. Characteristic exanthem and lymphadenopathy. Many infections are subclinical.

Clinical Manifestation. Characteristic exanthem and lymphadenopathy. Many infections are subclinical. Congenital Rubella Syndrome. Rubella virus infecting a pregnant female, while causing a benign illness in the mother, may result in serious chronic fetal infection and malformation.

Congenital Rubella Syndrome. Rubella virus infecting a pregnant female, while causing a benign illness in the mother, may result in serious chronic fetal infection and malformation. Prophylaxis. Childhood immunization is highly effective at preventing infection.

Prophylaxis. Childhood immunization is highly effective at preventing infection. Synonyms: German measles, “3-day measles.”

Synonyms: German measles, “3-day measles.” ICD-10: B05

ICD-10: B05

A highly contagious childhood viral disease characterized by fever, coryza, cough; an exanthema; conjunctivitis; pathognomonic enanthem (Koplik spots).

A highly contagious childhood viral disease characterized by fever, coryza, cough; an exanthema; conjunctivitis; pathognomonic enanthem (Koplik spots). Significant morbidity and mortality occur in acute and chronic course.

Significant morbidity and mortality occur in acute and chronic course. Childhood immunization is highly effective at preventing infection.

Childhood immunization is highly effective at preventing infection. Synonyms: Morbilli, rubeola.

Synonyms: Morbilli, rubeola. ICD-10: B34.1

ICD-10: B34.1

Etiologic Agents. Intestinal viruses echovirus 9 and 16, coxsackie A 16 virus, and enterovirus 71 (EV71).

Etiologic Agents. Intestinal viruses echovirus 9 and 16, coxsackie A 16 virus, and enterovirus 71 (EV71). Enteroviral Infections with Rash:

Enteroviral Infections with Rash: Echovirus 9 (E9): Discrete pink macules and papules resembling rubella ± fever.

Echovirus 9 (E9): Discrete pink macules and papules resembling rubella ± fever. Echovirus 16: exanthem, roseola-like (confluent pink papules) ± fever.

Echovirus 16: exanthem, roseola-like (confluent pink papules) ± fever. Coxsackievirus A16, EV71: hand foot and mouth disease.

Coxsackievirus A16, EV71: hand foot and mouth disease. A1–10, 16, 22, CB1–5; EV6, 9, 11, 16, 17, 25; EV71: Herpangina.

A1–10, 16, 22, CB1–5; EV6, 9, 11, 16, 17, 25; EV71: Herpangina. Other enteroviruses reported to cause erythema multiforme: vesicular, urticarial, petechial, and purpuric rashes.

Other enteroviruses reported to cause erythema multiforme: vesicular, urticarial, petechial, and purpuric rashes. ICD-10: 074.3

ICD-10: 074.3

Systemic viral infection characterized by ulcerative enanthem; vesicular exanthem on the distal extremities; mild constitutional symptoms.

Systemic viral infection characterized by ulcerative enanthem; vesicular exanthem on the distal extremities; mild constitutional symptoms. Etiology. Enterovirus (picornavirus group, single-stranded RNA, nonenveloped). Commonly: coxsackievirus A16 and EV71.

Etiology. Enterovirus (picornavirus group, single-stranded RNA, nonenveloped). Commonly: coxsackievirus A16 and EV71. Demography. Most common in first decade. Outbreaks during warmer months (late summer, early fall) in temperate climes. Highly contagious, spread from person to person by oral–oral and fecal–oral routes.

Demography. Most common in first decade. Outbreaks during warmer months (late summer, early fall) in temperate climes. Highly contagious, spread from person to person by oral–oral and fecal–oral routes. Pathogenesis. Enteroviral implantation in the GI tract (buccal mucosa and ileum) with extension into regional lymph nodes. Seventy-two hours later viremia occurs with seeding of the oral mucosa and skin of the hands and feet.

Pathogenesis. Enteroviral implantation in the GI tract (buccal mucosa and ileum) with extension into regional lymph nodes. Seventy-two hours later viremia occurs with seeding of the oral mucosa and skin of the hands and feet.