Bacterial Colonizations and Infections of Skin and Soft Tissues

The human microbiome or microbiota represents diverse viral, bacterial, fungal, and other species that live on and within us. They are part of us and we are part of this complex ecosystem. The human body contains >10 times more microbial cells than human cells. Skin supports a range of microbial communities that live in distinct niches. Microbial colonization of skin is more dense in humid intertriginous and occluded sites such as axillae, anogenital regions, and webspaces of feet. An intact stratum corneum is the most important defense against invasion of pathogenic bacteria.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci normally colonize skin shortly after birth and are not considered to be pathogens when cultured from skin.

Overgrowth of flora in occluded areas of results in clinical syndromes of erythrasma, pitted keratolysis, and trichomycosis.

Pyoderma is an archaic term, literally “pus in the skin.” Skin and soft-tissue infections, commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus and group A streptococcus (GAS), have been referred to a “pyoderma.” Pyoderma gangrenosum is a noninfectious inflammatory process, often associated with a systemic disorder such as inflammatory bowel disease.

S. aureus colonizes the nares and intertriginous skin intermittently, can penetrate the stratum corneum, and cause skin infections, e.g., impetigo, folliculitis. Deeper infection results in soft-tissue infections. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is an important pathogen for community-acquired (CA-MRSA) and healthcare-acquired (HA-MRSA) infections. MRSA strain USA300 is the major cause of skin and soft tissue as well as more invasive infections in community and health-care settings.

GAS usually colonizes the skin first and then the nasopharynx. Group B streptococcus (GBS; Streptococcus agalactiae) and group G β-hemolytic streptococci (GGS) colonize the perineum of some individuals and may cause superficial and invasive infections.

Cutaneous production of toxins by bacteria (S. aureus and GAS) causes systemic intoxications such as toxic shock syndrome (TSS) and scarlet fever.

Clinical Manifestation

Asymptomatic except for subtle discoloration.

Patches, sharply marginated (Fig. 25-1). Tan or pinkish; postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in more heavily pigmented individuals.

Figure 25-1. Erythrasma: axillaSharply marginated, red patch in the axilla. Wood’s lamp demonstrates bright coral-red, differentiating erythrasma from intertriginous psoriasis. KOH preparation was negative for hyphae.

In webspaces of feet, may be macerated (Fig. 25-2). Distribution: intertriginous skin, i.e., toe webs (Fig. 25-2), inguinal folds, axillae, other occluded sites.

Figure 25-2. Erythrasma: webspaceThis macerated interdigital webspace appeared bright coral-red when examined with Wood’s lamp; KOH preparation was negative for hyphae. The webspace is the most common site for erythrasma in temperate climates. In some cases, interdigital tinea pedis and/or pseudomonal intertrigo may coexist.

Diagnosis

Wood’s lamp examination demonstrates corral-red fluorescence. KOH negative; rule out epidermal dermatophytosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Intertriginous psoriasis, epidermal dermatophytosis, pityriasis versicolor, Hailey-Hailey disease.

Course

Persists and recurs unless microclimate is altered.

Treatment

Usually controlled with benzoyl peroxide wash or sanitizing alcohol gel. Clindamycin lotion and erythromycin are beneficial.

Clinical Manifestation

Punched out pits in stratum corneum, 1-8 mm in diameter (Fig. 25-3). Pits can remain discrete or become confluent, forming large areas of eroded stratum corneum. Lesions are more apparent with hyperhidrosis and maceration. Symmetric or asymmetric involvement of both feet. Distribution: Pressure-bearing areas, ventral aspect of toe, ball of foot, heel; interface of toes.

Figure 25-3. Pitted keratolysis: plantarThe stratum corneum of the anterior plantar foot shows erosion with well-demarcated scalloped margins, formed by the confluence of multiple, confluent “pits” (defects in the stratum corneum).

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis. KOH to rule out tinea pedis.

Differential Diagnosis

Concomitant tinea pedis, erythrasma, candidal intertrigo, and pseudomonal webspace infection may be present.

Course

Persists and recurs unless microclimate is altered.

Treatment

Usually controlled with benzoyl peroxide wash or sanitizing alcohol gel.

Figure 25-4. Trichomycosis axillaris 40-year-old obese male. Axillary hairs have cream-color encrustation. Numerous skin tags are also seen.

Infectious Intertrigo

Bacterial

• Beta-hemolytic streptococci. Group A (Fig. 25-5), group B, group G (Fig. 25-6). Streptococcal intertrigo can progress to soft-tissue infection (Fig. 25-6).

• S. aureus. Often gains entry into skin via hair follicle, causing folliculitis and furuncles.

• Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Fig. 25-7).

• C. minutissimum (erythrasma) (Figs. 25-1 and 25-2). K. sedentarius (pitted keratolysis) (Fig. 25-3).

Figure 25-5. Intergluteal intertrigo: group A streptococcus A painful moist erythematous plaque in a male with intertriginous psoriasis, with foul odor. Infection resolved with penicillin VK.

Figure 25-6. Erysipelas: group G streptococcus 65-year-old male with sharply marginated erythematous plaque on buttocks. Portal of entry of infection was intergluteal intertrigo.

Figure 25-7. Webspace intertrigo: P. aeruginosa Erosion of a webspace of the foot with a bright red base and surrounding erythema. Tinea pedis (interdigital and moccasin patterns) and hyperhidrosis were also present, which facilitated growth of Pseudomonas.

Clinical Manifestation

Usually asymptomatic. Discomfort usually indicates infection rather than colonization. Soft-tissue infection can gain entry in S. aureus or streptococcal intertrigo.

Diagnosis

Identify pathogen by bacterial culture, Wood’s lamp examination, or KOH preparation.

Treatment

Identify and treat pathogen.

Epidemiology and Etiology

• S. aureus: methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA). Bullous impetigo: local production of epidermolytic toxin A-producing S. aureus, which also causes staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

• Beta-hemolytic streptococcus: group A.

S. aureus and GAS are not members of human skin microbiome. They may transiently colonize skin and cause superficial infections.

Demography. Secondary infections, any age. Primary infections most often occur in children.

Portals of Entry of Infection. Minor breaks in the skin most commonly. Facial lesions usually associated with S. aureus colonization of nares. Dermatoses such as atopic dermatitis or Hailey–Hailey disease. Traumatic wounds. Bacterial infections occur in other cutaneous infections.

Clinical Manifestation

Superficial infections often asymptomatic. Ecthyma may be painful and tender. Most superficial bacterial infections of the skin cannot be categorized as “impetigo.”

Impetigo. Erosions with crusts (Figs. 25-8 and 25-9). Golden-yellow crusts are often seen in impetigo but are hardly pathognomonic; 1- to >3-cm lesions; central healing often apparent if lesions present for several weeks (Fig. 25-9). Arrangement: scattered, discrete lesions; without therapy, lesions may become confluent; satellite lesions occur by autoinoculation. Secondary infection of various dermatoses is common (Figs. 25-10 and 25-11).

Figure 25-8. Impetigo: MSSA Crusted erythematous erasions becoming confluent on the nose, cheek, lips, and chin in a child with nasal carriage of S. aureus and mild facial eczema.

Figure 25-9. Impetigo: MRSA 45-year-old male with large crusted erosions, becoming confluent, with central clearing on the face. MRSA colonized the nares.

Figure 25-10. Secondary infection of Hailey-Hailey disease: MRSA 51-year-old female with Hailey-Hailey disease has chronic MRSA infection of cutaneous erosions on thigh.

Figure 25-11. Secondary infection of pemphigus foliaceus: MRSA 65-year-old female with recalcitrant pemphigus foliaceus has extensive infection of cutaneous erosions on the face.

Bullous Impetigo. Blisters containing clear yellow or slightly turbid fluid with erythematous halo, arising on normal-appearing skin (see “Localized Form” of “Staphylococcal-Scalded Skin Syndrome”). With rupture, bullous lesions decompress. If roof of bulla is removed, shallow moist erosion forms (Figs. 25-12 and 25-13). Distribution: more common in intertriginous sites.

Figure 25-12. Bullous impetigo Scattered, discrete, intact, and ruptured thin-walled blisters on the inguinal area and adjacent thigh of a child; lesions in the groin have ruptured, resulting in superficial erosions.

Figure 25-13. Bullous impetigo with blistering dactylitis: S. aureus A large, single bulla with surrounding erythema and edema on the thumb of a child; the bulla has ruptured and clear serum exudes.

Ecthyma. Ulceration with a thick adherent crust (Fig. 25-14). Lesions may be tender, indurated.

Figure 25-14. Ecthyma: MSSA Thickly crusted erosion/ulcer on the nose had been present for 6 weeks, arising at the site of a small wound. The crust was adherent and the site bled with debridement.

Differential Diagnosis

Impetigo. Excoriation, allergic contact dermatitis, herpes simplex, epidermal dermatophytosis, scabies. Most erosions with “honey-colored crusts” are not impetigo.

Intact Bullae. Acute allergic contact dermatitis, insect bites, thermal burns, porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) (dorsa of hands).

Ecthyma. Excoriations, excoriated insect bites, PCT, venous (stasis) and ischemic ulcers (legs).

Diagnosis

Clinical findings confirmed by culture: S. aureus, commonly; failure of oral antibiotic suggests MRSA. GAS.

Course

Untreated, lesions of impetigo become more extensive and ecthyma. With adequate treatment, prompt resolution. Lesions can progress to deeper skin and soft-tissue infections. Nonsuppurative complications of GAS infection include guttate psoriasis, scarlet fever, and glomerulonephritis. Ecthyma may heal with scarring. Recurrent S. aureus or GAS infections can occur because of failure to eradicate pathogen or by recolonization. Undiagnosed MRSA infection does not respond to usual oral antibiotics given for methicillin-sensitive S. aureus.

Treatment

Prevention. Benzoyl peroxide wash. Check family members for signs of impetigo. Ethanol or isopropyl gel for hands and/or involved sites.

Topical Treatment. Mupirocin and retapamulin ointment is highly effective in eliminating S. aureus from the nares and cutaneous lesions.

Systemic Antimicrobial Treatment. According to sensitivity of isolated organism.

Epidemiology and Etiology

S. aureus (MSSA, MRSA).

Other Organisms. Much less common.

Sterile abscess can occur as a foreign-body response (splinter, ruptured inclusion cyst, injection sites). Cutaneous odontogenic sinus can appear anywhere on the lower face, even at sites distant from the origin (see Fig. 33-23).

Folliculitis, furuncles, and carbuncles represent a continuum of severity of S. aureus infection. Portal of entry: ostium of hair follicle.

Clinical Manifestation

Folliculitis may be slightly tender. With deeper infection, pain and tenderness. Carbuncles may be accompanied by low-grade fever and malaise; lesions are red, hot, and painful/tender.

Abscess. May arise in any organ or tissue. Abscesses that present on the skin arise in the dermis, subcutaneous fat, muscle, or a variety of deeper structures. Initially, a tender red nodule forms. In time (days to weeks), pus collects within a central space (Fig. 25-15). A well-formed abscess is characterized by fluctuance of the central portion of the lesion. Arise at sites of trauma. Ruptured inclusion cyst on the back often present as painful abscess. When arising from S. aureus folliculitis, may be solitary or multiple.

Figure 25-15. Abscess: MSSA A very tender abscess with surrounding erythema on the heel. The patient was a diabetic patient with sensory neuropathy; puncture by a sewing needle that was imbedded in the heel had provided a portal of entry. The foreign body was removed surgically.

Folliculitis (Staphylococcal). See “Infectious Folliculitis” in Section 31.

Furuncle. Initially, a firm tender nodule, up to 1-2 cm in diameter. In many individuals, furuncles occur in setting of staphylococcal folliculitis. Nodule becomes fluctuant, with abscess formation ± central pustule. Nodule with cavitation remains after drainage of abscess. A variable zone of cellulitis may surround the furuncle. Distribution: any hair-bearing region—beard area, posterior neck and occipital scalp, axillae, buttocks. Solitary or multiple lesions (Figs. 25-16 to 25-20).

Figure 25-16. Furuncle: MSSA Abscess on the medial thigh of a 52-year-old male. The lesion was incised and drained and treated with doxycycline.

Figure 25-17. Furuncles and cellulitis: MRSA A 64-year-old male developed furuncles on the dorsum of the left hand (A) and forearm (B). He had a fistula on his forearm and was dialyzed three times per week. Infection was spreading from the abscess with cellulitis.

Figure 25-18. Multiple furuncles on the abdomen: MRSA 66-year-old operating room technician with multiple painful nodules. MRSA was isolated on culture of the nares and an abscess. He was treated with doxycycline, mupirocin to nares, and bleach baths. He was restricted from returning to work until cultured sites were negative for S. aureus colonization.

Figure 25-19. Multiple furuncles: MRSA Multiple painful nodules on the buttocks of a 44-year-old male with HIV disease.

Figure 25-20. Chronic abscess, botryomycosis: MRSA 41-year old with HIV disease had an extensive abscess for months, (A) R-buttock abscess, (B) The abscess was drained and treated with linezolid. (C) The white grains noted in the drainage represent colonies of S. aureus.

Carbuncle. Evolution is similar to that of furuncle. Composed of several to multiple, adjacent, coalescing furuncles (Fig. 25-21). Characterized by multiple loculated dermal and subcutaneous abscesses, superficial pustules, necrotic plugs, and sieve-like openings draining pus.

Figure 25-21. Carbuncle: MSSA A very large, inflammatory plaque studded with pustules, draining pus, on the nape of the neck. Infection extends down to the fascia and has formed from a confluence of many furuncles.

Differential Diagnosis

Painful Dermal/Subcutaneous Nodule. Ruptured epidermoid or pilar cyst, hidradenitis suppurativa (axillae, groin, vulva).

Diagnosis

Clinical findings confirmed by findings on Gram staining and culture.

Course

Most abscesses resolve with effective treatment. If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, furunculosis can be complicated by soft-tissue infection, bacteremia, and hematogenous seeding of viscera. Some individuals are subject to recurrent furunculosis, particularly diabetics.

Treatment

The treatment of an abscess, furuncle, or carbuncle is incision and drainage plus systemic antimicrobial therapy.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Etiology.Adults: S. aureus, GAS.

Less commonly beta-homolytic streptococcus: group B, C, or G. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae (erysipeloid); P. aeruginosa, Pasteurella multocida, Vibrio vulnificus; Mycobacterium fortuitum complex. In children: pneumococci, Neisseria meningitidis group B (periorbital). Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infections much less common because of Hib immunization.

Chronic Soft-Tissue Infections. Nocardia brasiliensis, Sporothrix schenckii, Madurella species, Scedosporium species, nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM).

Dog and Cat Saliva and Bites: P. multocida and other Pasteurella species. Capnocytophaga canimorsus (see Fig. 25-55).

Portal of Infection. Pathogens gain entry via any break in the skin or mucosa. Tinea pedis and leg and foot ulcers are common portals. Infections follow bacteremia/sepsis with cutaneous seeding.

Risk Factors. Host defense defects, diabetes mellitus, drug and alcohol abuse, cancer and cancer chemotherapy, chronic lymphedema [postmastectomy (see Fig. 25-25), previous episode of cellulitis/erysipelas].

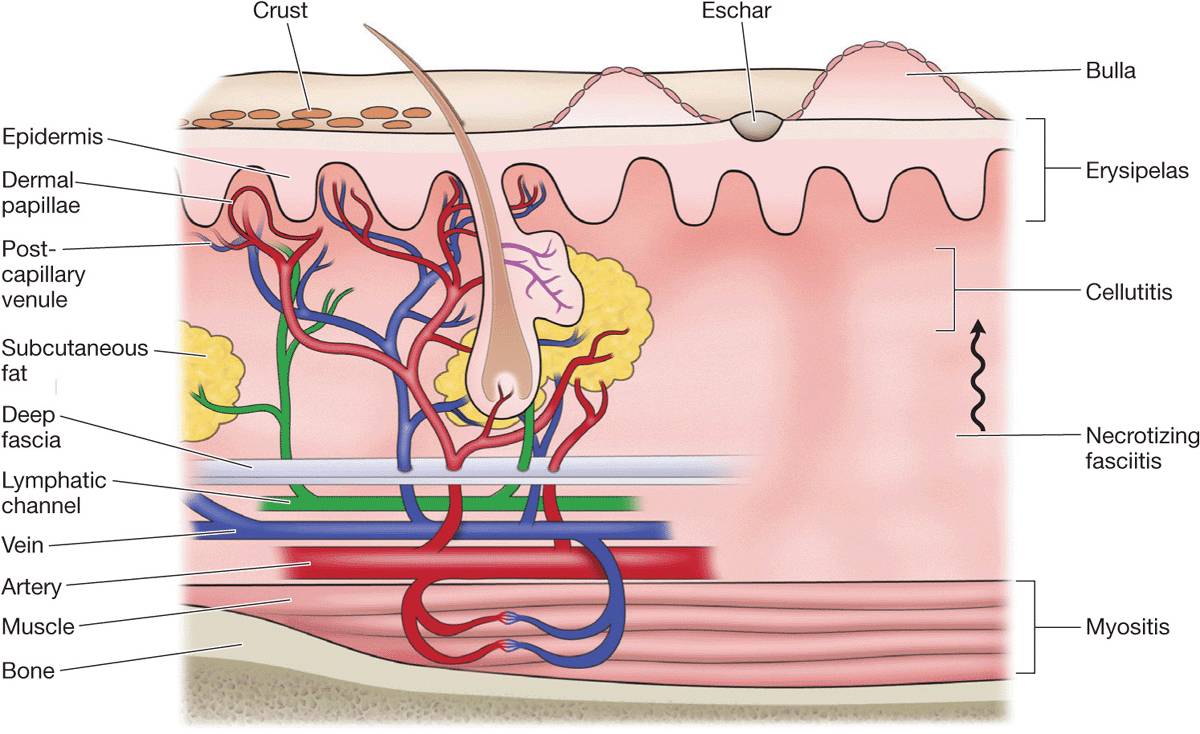

After entry, infection spreads to tissue spaces and cleavage planes (Fig. 25-22) as hyaluronidases break down polysaccharide ground substances, fibrinolysins digest fibrin barriers, lecithinases destroy cell membranes. Local tissue devitalization is usually required to allow for significant anaerobic bacterial infection. The number of infecting organisms is usually small, suggesting that cellulitis may be more of a reaction to cytokines and bacterial superantigens than to overwhelming tissue infection.

Figure 25-22. Structural components of the skin and soft tissue, superficial infections, and infections of the deeper structures. The rich capillary network beneath the dermal papillae plays a key role in the localization of infection and in the development of the acute inflammatory reaction. [From Stevens DL. Infections of the skin, muscles, and soft tissues. In Longo DL et al. (eds.). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 18th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2012.]

Clinical Manifestation

Symptoms of fever and chills can develop before cellulitis is clinically apparent. Higher fever (3B.5°C) and chills usually associated with GAS infection. Local pain and tenderness. Necrotizing infections associated with more local pain and systemic symptoms.

Red, hot, edematous, shiny plaque originating at the portal of entry. Enlarges with proximal extension (Figs. 25-23 and 25-24); borders usually sharply defined, irregular, and slightly elevated. Vesicles, bullae, erosions, abscesses, hemorrhage, and necrosis may form in plaque (Fig. 25-24). Lymphangitis. Lymph nodes can be enlarged and tender, regionally.

Figure 25-23. Cellulitis at portal of entry: MSSA 51-year-old male with interdigital tinea pedis noted pain on the dorsum of his foot. KOH preparation was positive for dermatophytic hyphae. Methicillin-sensitive S. aureus was isolated on culture of the webspace.

Figure 25-24. Cellulitis lower leg: MRSA 70-year-old obese male with chronic venous stasis and stasis ulcer had increasing erythema and blister formation of the lower leg associated with fever.

Distribution. Adults. Lower leg most common site (Fig. 25-24). Arm: In young male, consider IV drug use; in female, postmastectomy (Fig. 25-25). Trunk: operative wound site. Face: following rhinitis, conjunctivitis, pharyngitis; associated with colonization of nares by S. aureus and of pharynx by GAS.

Figure 25-25. Recurrent cellulitis of the arm with chronic lymphedema: MSSA Right breast cancer had been treated with mastectomy and lymph node excision 10 years previously. Lymphedema of the right arm followed. Hand dermatitis was secondarily infected with MSSA. Cellulitis occurred repeatedly in the setting of chronic lymphedema.

Variants of Cellulitis by Pathogen

S. aureus: Portal of entry is usually apparent; cellulitis is an extension of focal infection. Toxin syndromes: scalded-skin syndrome, TSS. Endocarditis may follow bacteremia.

Beta-hemolytic streptococci GAS (Streptococcus pyogenes) colonize skin and oropharynx. GBS and GGS colonize anogenital region (Fig. 25-26). Beta-hemolytic streptococcal soft-tissue infections spread rapidly along superficial cutaneous lymphatic vessels, presenting a tender red expanding plaques, i.e., erysipelas (Fig. 25-27). Following childbirth, known as puerperal sepsis; infection can extend into pelvis. GBS cellulitis occurs in neonates; high morbidity and mortality. GAS infection with necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal TSS has high morbidity and mortality.

Figure 25-26. Erysipelas of buttocks: group B streptococcus 40-year-old female with history of Crohn disease with ileostomy, prior surgery for hidradenitis, and invasive vulvar carcinoma; treated with radiation. Portal of entry was intergluteal cleft. Presented with fever and local tenderness for 1 day.

Figure 25-27. Erysipelas of face: group A streptococcus Painful, well-defined, shiny, erythematous, edematous plaques involving the central face of an otherwise healthy male. On palpation, the skin is hot and tender.

E. rhusiopathiae: Erysipeloid occurs in individuals who handle game, poultry, fish. Painful, inflamed plaque with sharply defined irregular raised border occurring at the site of inoculation, i.e., finger or hand (Fig. 25-28), spreading to wrist and forearm. Color: purplish red acutely; brownish with resolution. Enlarges peripherally with central fading. Usually no systemic symptoms.

Figure 25-28. Erysipeloid of hand A well demarcated, violaceous, cellulitic plaque (without epidermal changes of scale or vesiculation) on the dorsa of the hand and fingers, occurred following cleaning fish; the site was somewhat painful, tender, and warm.

Ecthyma gangrenosum: Rare variant of necrotizing soft-tissue infection caused by P. aeruginosa. Clinically characterized by infarcted center with erythematous halo, expanding rapidly without effective treatment (Fig. 25-29). Distribution: most commonly in the axilla, groin, perineum. Prognosis depends on prompt restoration of host defense defects, usually on correction of neutropenia. When occurring as a local infection in the absence of bacteremia, prognosis is much more favorable.

Figure 25-29. Ecthyma gangrenosum of buttock: P. aeruginosa A 30-year-old male with HIV disease and neutropenia. (A) An extremely painful, infarcted area with surrounding erythema present for 5 days. This primary cutaneous infection was associated with bacteremia. (B) Two weeks later, the lesion had progressed to a large ulceration. The patient died 3 months later of P. aeruginosa pneumonitis associated with chronic neutropenia.

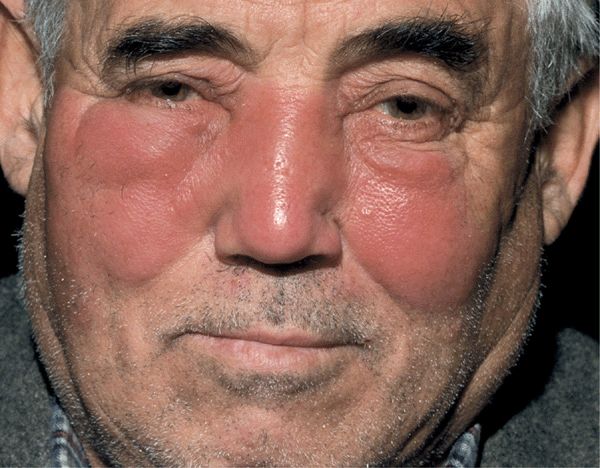

H. influenzae: Occurs mainly in children <2 years. Cheek, periorbital area, head, and neck are most common sites. Clinically, swelling, characteristic violaceous erythema hue. Use of Hib vaccine has dramatically reduced incidence.

V. vulnificus, V. cholerae non-01 and non-0139. Underlying disorders: cirrhosis, diabetes, immunosuppression, hemochromatosis, thalassemia. Follows ingestion of raw/under-cooked seafood, gastroenteritis, bacteremia with seeding of skin; also exposure of skin to seawater. Characterized by bulla formation, necrotizing vasculitis (Fig. 25-30). Usually on the extremities; often bilateral.

Figure 25-30. Bilateral cellulitis of legs: V. vulnificus Bilateral hemorrhagic plaques and bullae on the legs, ankles, and feet of an older diabetic with cirrhosis. Unlike other types of cellulitis in which microorganisms enter the skin locally, which is caused by V. vulnificus, usually follows a primary enteritis with bacteremia and dissemination to the skin. Most cases initially diagnosed as bilateral cellulitis are inflammatory (eczema, stasis dermatitis, psoriasis) rather than infectious.

Aeromonas hydrophila: Water-associated trauma; preexisting wound. Immunocompromised host. Lower leg. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection.

C. canimorsus. Immunosuppression or asplenia; exposure to dog saliva or bite. Causes fulminant sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (see Fig. 25-57).

P. multocida: Most common cause of infection following animal bite; soft-tissue infection.

Clostridium species. Associated with trauma; contamination by soil or feces; malignant intestinal tumor. Infection characterized by gas production (crepitation on palpation), marked systemic toxicity. Necrotizing infection.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (see p. 579). History of recent surgery, injection, penetrating wound, systemic corticosteroid therapy. Low-grade cellulitis. Multiple sites of infection. Systemic findings lacking.

Cryptococcus neoformans: Patient always immunocompromised. Red, hot, tender, edematous plaque on extremity. Rarely multiple noncontiguous sites.

Mucormycosis: Usually occurring in individual with uncontrolled diabetes.

Nocardiosis: See Cutaneous Nocardia Infections.

Eumycetoma: See Section 26.

Chromoblastomycosis: See Section 26.

Differential Diagnosis

Erysipelas/Cellulitis. Deep vein thrombophlebitis, early contact dermatitis, urticaria, insect bite (hypersensitivity response), fixed drug eruption, erythema nodosum, acute gout, erythema migrans (EM).

Necrotizing STIs. Vasculitis, embolism with infarction of skin, peripheral vascular disease, calciphylaxis, warfarin necrosis, traumatic injury, cryoglobulinemia, fixed drug eruption, pyoderma gangrenosum, brown recluse spider bite.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis is based on morphologic features of lesion and the clinical setting, i.e., underlying diseases, travel history, animal exposure, history of bite, and age. Confirmed by culture in only 29% of cases in immunocompetent patients. Suspicion of necrotizing fasciitis requires immediate deep biopsy and frozen-section histopathology.

Course

With timely diagnosis and treatment, soft-tissue infection resolves with oral or parenteral antibiotic treatment.

Dissemination of infection (lymphatics, hematogenously) with metastatic sites of infection occurs if effective treatment is delayed. In immunocompromised patients, prognosis depends on prompt restoration of altered immunity, usually on correction of neutropenia. Without surgical debridement, necrotizing fasciitis is fatal.

Treatment

Systemic high dose antibiotic treatment according to type and sensitivity of microbial organism.

Clinical Manifestation

Local redness, edema, warmth, pain in the involved site, typically on an extremity.

Characteristic findings appear within 36-72 h after onset: involved soft tissue becomes dusky blue in color; vesicles or bullae appear. Infection spreads rapidly along fascial planes (Fig. 25-31). Extensive, cutaneous soft-tissue necrosis develops. Involved tissue may be anesthetic. Necrosis manifests as a black eschar with surrounding irregular border of erythema. Fever and other constitutional symptoms are prominent as the inflammatory process extends rapidly over the next few days. Streptococcal TSS occurs with GAS, GBS, GCS, GGS. Metastatic abscesses may occur as a consequence of bacteremia. Secondary thrombophlebitis occurs.

Figure 25-31. Necrotizing fasciitis of buttock Black eschar within an erythematous, edematous plaque involving the entire buttock with rapidly progressive area of necrosis. GAS, GBS, GCS, GGS. Metastatic abscesses may occur as a consequence of bacteremia. Secondary thrombophlebitis occurs.

Differential Diagnosis

Pyoderma gangrenosum, calciphylaxis, ischemic necrosis, warfarin necrosis, pressure ulcer, brown recluse spider bite.

Treatment

Surgical Debridement. Requires early and complete surgical debridement of necrotic tissue in combination with high-dose antimicrobial agents.

Clinical Manifestation

Acute Lymphangitis. Portal of entry: Break in skin, wound, S. aureus paronychia, primary herpes simplex infection. Pain and/or erythema proximal to break in skin. Red linear streaks and palpable lymphatic cords, up to several centimeters in width, extend from the local lesion toward the regional lymph nodes (Fig. 25-32), which are usually enlarged and tender.

Figure 25-32. Acute lymphangitis of forearm: S. aureus A small area of the cellulitis on the volar wrist with a tender linear streak extending proximally up the arm; the infection spreads from the portal of entry within the superficial lymphatic vessels.

Subacute and chronic lymphangitis; nodular lymphangitis; see discussion on Nocardiosis, NTM infection, and sporotrichosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Linear Lesions on Extremities. Phyto-allergic contact dermatitis (poison ivy or oak), phytophotodermatitis, superficial thrombophlebitis.

Nodular Lymphangitis. M. marinum, N. brasiliensis, S. schenckii infection.

Diagnosis

The combination of an acute peripheral lesion with proximal tender/painful red linear streaks leading toward regional lymph nodes is diagnostic of lymphangitis. Isolate S. aureus or GAS from portal of entry.

Course

Resolves with correct diagnosis and treatment. Bacteremia with metastatic infection in various organs uncommon with adequate treatment.

Treatment

Systemic antibiotic depending on causative organism.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Classification. Traumatic wounds: Open or closed wounds (Fig. 25-33). Surgical wounds: Infection in surgical incisions (Fig. 25-34). Burn wounds: Burn wound may become superficially colonized with S. aureus; open burn-related surgical wound infection; burn wound cellulitis; invasive infection in debrided burn wounds (Fig. 25-35). Chronic ulcers: Arterial insufficiency; venous insufficiency; neuropathic ulcers/diabetes mellitus; pressure ulcers (bedsores) (Figs. 25-36 to 25-38). Bites: Animal; human; insect.

Figure 25-33. Laceration infection in renal transplant recipient: MRSA 60-year-old male immunosuppressed renal transplant recipient was unaware of a laceration on the calf. Erythema and induration are seen around the crusted wound. MRSA was isolated on culture. Two circled invasive squamous cell carcinomas are also seen on the calf.

Figure 25-34. Surgical excision wound infection: MSSA Surgical wound became painful and tender 7 days after excision of squamous cell carcinoma; soft tissue (cellulitis) is seen adjacent to the wound margin. Necrotic tissue is seen in the base.

Figure 25-35. Burn wound infection: MSSA 10-year-old male with extensive third degree thermal burn treated with autologous skin grafting has extensive new crusted erosions. MSSA was cultured from the infected site.

Figure 25-36. Wound infection of stasis ulcer 75-year-old female with varicose veins and enlarging stasis ulcer infected with MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. IV antibiotics were administered. Incompetent veins were treated with endovascular laser ablation. The ulcer healed with minimal scar.

Figure 25-37. Infection of diabetic ulcer: MRSA 86-year-old male with diabetes mellitus type 2 had a chronic neuropathic ulcer on the R-lateral foot. The ulcer rapidly enlarged associated with fever and glucose of 450 mg/dL. MSSA was isolated from the wound. He was hospitalized and treated with IV antibiotics. He died 3 months later.

Figure 25-38. Wound infection and cellulitis: MRSA 53-year-old male with obsessive-compulsive disorder excoriates extremities in the evening. MRSA infection has occurred repeatedly. Ulcers resolved with doxycycline, doxepin, and unna boots applied weekly.

Epidemiology. S. aureus in the most common pathogen in wound infections, MSSA and increasingly MRSA. Surgical wound infection is up to 10 times more likely among patients who harbor S. aureus in nares. Hospital-acquired (nosocomial) or health-care-associated infections (most commonly surgical wound infections) are the most common complication affecting hospitalized patients.

Pathogenesis. Wounds are initially colonized by skin flora or introduced organisms. In some cases, these organisms proliferate, causing a host inflammatory response defined as infection.

Clinical Manifestation

Local Infection. Tenderness of wound area, erythema, hot, purulent drainage, induration. Invasive infection: malaise, anorexia, sweats, fever, chills. Sepsis syndrome: fever, hypotension. Types of Surgical Infections. Superficial infection of wound, wound infection with soft-tissue infection, i.e., cellulitis and erysipelas, soft-tissue abscess, necrotizing soft-tissue infection, tetanus.

Differential Diagnosis

Allergic contact dermatitis (e.g., neomycin), pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis.

Diagnosis

Because all open wounds are colonized with microorganisms, diagnosis of infection relies on the clinical characteristics of the wound. Wound culture identifies the potential pathogen(s).

Treatment

Although all wounds require treatment, only infected lesions require antimicrobial therapy.

ICD-10: L08.1

ICD-10: L08.1

Etiology.Corynebacterium minutissimum, grampositive (diphtheroid) bacillus; normally in human microbiome. Growth favored by humid cutaneous microclimate.

Etiology.Corynebacterium minutissimum, grampositive (diphtheroid) bacillus; normally in human microbiome. Growth favored by humid cutaneous microclimate.

Etiology.Kytococcus Sedentarius. One of human microbiome on plantar feet in the setting of hyperhidrosis; produces two extracellular proteases that can digest keratin.

Etiology.Kytococcus Sedentarius. One of human microbiome on plantar feet in the setting of hyperhidrosis; produces two extracellular proteases that can digest keratin. ICD-10: A48.8/L08.8

ICD-10: A48.8/L08.8

Superficial colonization on hair shafts in sweaty regions, axillary and pubic.

Superficial colonization on hair shafts in sweaty regions, axillary and pubic. Etiology.Corynebacterium tenuis and other corynebacterial species; gram-positive diphtheroid. Not fungus.

Etiology.Corynebacterium tenuis and other corynebacterial species; gram-positive diphtheroid. Not fungus. Granular concretions (yellow, black, or red) on hair shaft (

Granular concretions (yellow, black, or red) on hair shaft ( Treatment. Usually controlled with benzoyl peroxide wash or sanitizing alcohol gel. Antiperspirants. Shaving area.

Treatment. Usually controlled with benzoyl peroxide wash or sanitizing alcohol gel. Antiperspirants. Shaving area. ICD-10: L30.4

ICD-10: L30.4

Intertrigo (Latin inter, “between”; trigo, “rubbing”).

Intertrigo (Latin inter, “between”; trigo, “rubbing”). Inflammation of opposed skin (inframammary regions, axillae, groins, gluteal folds, redundant skin folds of obese persons). May represent inflammatory dermatosis or superficial colonization or infection.

Inflammation of opposed skin (inframammary regions, axillae, groins, gluteal folds, redundant skin folds of obese persons). May represent inflammatory dermatosis or superficial colonization or infection. Dermatoses occurring in intertriginous skin. Intertriginous psoriasis. Also seborrheic dermatitis, Hailey–Hailey disease, Langerhans cell histiocytosis. S. aureus and streptococcus can cause secondary infection of these dermatoses.

Dermatoses occurring in intertriginous skin. Intertriginous psoriasis. Also seborrheic dermatitis, Hailey–Hailey disease, Langerhans cell histiocytosis. S. aureus and streptococcus can cause secondary infection of these dermatoses. ICD-10: B08.0

ICD-10: B08.0

Etiology. S. aureus; GAS.

Etiology. S. aureus; GAS. Portal of Entry. Impetigo occurs adjacent to the site of S. aureus colonization such as the nares (see

Portal of Entry. Impetigo occurs adjacent to the site of S. aureus colonization such as the nares (see  Clinical Manifestation. Crusted erosions.

Clinical Manifestation. Crusted erosions. Treatment

Treatment Reduced colonization.

Reduced colonization. Topical antibiotic to infected and colonized sites; systemic antibiotic.

Topical antibiotic to infected and colonized sites; systemic antibiotic. ICD-10: L02

ICD-10: L02

Deeper skin infections can follow traumatic inoculation into skin or extension of infection into hair follicles.

Deeper skin infections can follow traumatic inoculation into skin or extension of infection into hair follicles. Abscess: Acute or chronic localized inflammation, associated with a collection of pus accumulated in a tissue. Inflammatory response to an infectious process or foreign material.

Abscess: Acute or chronic localized inflammation, associated with a collection of pus accumulated in a tissue. Inflammatory response to an infectious process or foreign material. Folliculitis: Infection of hair follicle with ± pus in the ostium of follicle (see

Folliculitis: Infection of hair follicle with ± pus in the ostium of follicle (see  Furuncle: Acute, deep-seated, red, hot, tender nodule or abscess (boil) that evolves from a staphylococcal folliculitis.

Furuncle: Acute, deep-seated, red, hot, tender nodule or abscess (boil) that evolves from a staphylococcal folliculitis. Carbuncle: Deeper infection composed of interconnecting abscesses usually arising in several contiguous hair follicles.

Carbuncle: Deeper infection composed of interconnecting abscesses usually arising in several contiguous hair follicles. Characterized by inflammation of skin and adjacent subcutaneous tissues. Soft tissue refers to tissues that connect, support, or surround other structures and organs: skin, adipose tissue, fibrous tissues, fascia, tendon, ligaments.

Characterized by inflammation of skin and adjacent subcutaneous tissues. Soft tissue refers to tissues that connect, support, or surround other structures and organs: skin, adipose tissue, fibrous tissues, fascia, tendon, ligaments. Syndromes. Cellulitis, erysipelas, lymphangitis, necrotizing fasciitis, wound infection.

Syndromes. Cellulitis, erysipelas, lymphangitis, necrotizing fasciitis, wound infection. Soft-Tissue Inflammation. Although often infectious, soft-tissue inflammation can be a manifestation of a noninfectious reaction pattern such as with neutrophilic dermatoses, erythema nodosum, and eosinophilic cellulitis.

Soft-Tissue Inflammation. Although often infectious, soft-tissue inflammation can be a manifestation of a noninfectious reaction pattern such as with neutrophilic dermatoses, erythema nodosum, and eosinophilic cellulitis. Cellulitis. Usually begins at a portal of entry in the skin, spreading proximally as an expanding solitary lesion. Uncommonly, soft-tissue infection can follow hematogenous dissemination with multiple sites of infection. Cellulitis is most often acute, caused by S. aureus.

Cellulitis. Usually begins at a portal of entry in the skin, spreading proximally as an expanding solitary lesion. Uncommonly, soft-tissue infection can follow hematogenous dissemination with multiple sites of infection. Cellulitis is most often acute, caused by S. aureus. Acute Inflammation. Due to cytokines and bacterial superantigens rather than to overwhelming tissue infection.

Acute Inflammation. Due to cytokines and bacterial superantigens rather than to overwhelming tissue infection. Chronic Soft-Tissue Infection. Nocardiosis, sporotrichosis, and phaeohyphomycosis.

Chronic Soft-Tissue Infection. Nocardiosis, sporotrichosis, and phaeohyphomycosis. ICD-10: A46.0

ICD-10: A46.0

Acute, spreading infection of dermal and subcutaneous tissues. Characterized by a red, hot, tender area of skin. Portal of entry of infection is usually apparent. Most common pathogen is S. aureus. Erysipelas is a variant of cellulitis involving cutaneous lymphatics, and is usually caused by beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Acute, spreading infection of dermal and subcutaneous tissues. Characterized by a red, hot, tender area of skin. Portal of entry of infection is usually apparent. Most common pathogen is S. aureus. Erysipelas is a variant of cellulitis involving cutaneous lymphatics, and is usually caused by beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Characterized by rapid progression of infection with extensive necrosis of soft tissues and overlying skin. Necrotizing fasciitis.

Characterized by rapid progression of infection with extensive necrosis of soft tissues and overlying skin. Necrotizing fasciitis. Etiology. Caused by beta-hemolytic GAS. Less commonly, groups B, C, or G. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections also caused by P. aeruginosa, Clostridium species, mixed infection with anaerobes.

Etiology. Caused by beta-hemolytic GAS. Less commonly, groups B, C, or G. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections also caused by P. aeruginosa, Clostridium species, mixed infection with anaerobes. Portal of Entry. May begin deep at site of nonpenetrating minor trauma (bruise, muscle strain). Minor trauma, laceration, needle puncture, or surgical incision on an extremity. GAS may be seeded to this site during transient bacteremia. Clinical variants of necrotizing soft-tissue infection differ with causative organism, anatomic location of infection, underlying conditions. Streptococcal necrotizing myositis occurs as a primary myositis. Streptococcal TSS may occur with GAS necrotizing fasciitis. GBS causes necrotizing fasciitis in episiotomy incisions.

Portal of Entry. May begin deep at site of nonpenetrating minor trauma (bruise, muscle strain). Minor trauma, laceration, needle puncture, or surgical incision on an extremity. GAS may be seeded to this site during transient bacteremia. Clinical variants of necrotizing soft-tissue infection differ with causative organism, anatomic location of infection, underlying conditions. Streptococcal necrotizing myositis occurs as a primary myositis. Streptococcal TSS may occur with GAS necrotizing fasciitis. GBS causes necrotizing fasciitis in episiotomy incisions. Diagnosis. Imperative in understanding pathogenesis and deciding on the appropriate antimicrobial and surgical therapies.

Diagnosis. Imperative in understanding pathogenesis and deciding on the appropriate antimicrobial and surgical therapies. When skin necrosis is not obvious, diagnosis must be suspected if there are signs of severe sepsis and/or some of the following local symptoms/signs: severe spontaneous pain, indurated edema, bullae, cyanosis, skin pallor, skin hypesthesia, crepitation, muscle weakness, foul smelling exudates.

When skin necrosis is not obvious, diagnosis must be suspected if there are signs of severe sepsis and/or some of the following local symptoms/signs: severe spontaneous pain, indurated edema, bullae, cyanosis, skin pallor, skin hypesthesia, crepitation, muscle weakness, foul smelling exudates. ICD-10: 189-1

ICD-10: 189-1

An inflammatory process involving the subcutaneous lymphatic channels.

An inflammatory process involving the subcutaneous lymphatic channels. Etiology

Etiology Acute lymphangitis: GAS; S. aureus; other bacteria. Herpes simplex virus.

Acute lymphangitis: GAS; S. aureus; other bacteria. Herpes simplex virus. Subacute to chronic nodular lymphangitis: Mycobacterium marinum, other NTM, Sporotrix schenkii, N. brasiliensis.

Subacute to chronic nodular lymphangitis: Mycobacterium marinum, other NTM, Sporotrix schenkii, N. brasiliensis.

Wound. Injury in which skin is surgically incised or traumatically injured (open wound) or in which blunt force trauma causes a contusion (closed wound). Wound infection: Skin and all wounds are colonized by bacteria and other microbes, i.e., cutaneous microbiome. Infection is characterized by pain, tenderness, purulence, erythema, warmth, and must be diagnosed on clinical as well as culture findings.

Wound. Injury in which skin is surgically incised or traumatically injured (open wound) or in which blunt force trauma causes a contusion (closed wound). Wound infection: Skin and all wounds are colonized by bacteria and other microbes, i.e., cutaneous microbiome. Infection is characterized by pain, tenderness, purulence, erythema, warmth, and must be diagnosed on clinical as well as culture findings. Bacteria colonize skin and mucosa (mucocutanous microbiome), replicate locally, and elaborate toxins that cause local mucocutaneous and systemic disorders.

Bacteria colonize skin and mucosa (mucocutanous microbiome), replicate locally, and elaborate toxins that cause local mucocutaneous and systemic disorders. Clinical syndromes caused by these toxins:

Clinical syndromes caused by these toxins: S. aureus

S. aureus Bullous impetigo (see

Bullous impetigo (see  Staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Generalized form with extensive epidermolysis, followed by desquamation (

Staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Generalized form with extensive epidermolysis, followed by desquamation ( TSS. Abortive form, staphylococcal scarlet fever.

TSS. Abortive form, staphylococcal scarlet fever. GAS

GAS Scarlet fever

Scarlet fever Streptococcal TSS

Streptococcal TSS Bacillus anthracis: Anthrax

Bacillus anthracis: Anthrax Corynebacterium diphtheriae: Diphtheria

Corynebacterium diphtheriae: Diphtheria Clostridium tetani: Tetanus

Clostridium tetani: Tetanus ICD-10: L00

ICD-10: L00

Etiology. S. aureus producing exfoliative toxins. Occurs in neonates and young children.

Etiology. S. aureus producing exfoliative toxins. Occurs in neonates and young children. Pathogenesis. Illness develops after toxin synthesis and absorption and the subsequent toxin-initiated host response. Exotoxins cleave desmoglein-1 in epidermal granular cell-layer desmosomes that link adjoining cells. Exotoxins are proteases that cleave desmoglein-1, which normally hold the granulosum and spinulosum layers together. Antitoxin antibodies are protective against SSSS and TSS.

Pathogenesis. Illness develops after toxin synthesis and absorption and the subsequent toxin-initiated host response. Exotoxins cleave desmoglein-1 in epidermal granular cell-layer desmosomes that link adjoining cells. Exotoxins are proteases that cleave desmoglein-1, which normally hold the granulosum and spinulosum layers together. Antitoxin antibodies are protective against SSSS and TSS.